2. 河南农业大学牧医工程学院,郑州 450002;

3. 河南省饲料与养殖环境控制工程技术研究中心 河南省畜禽繁育与营养调控重点实验室,郑州 450002

2. College of Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou 450002;

3. Henan Center for Feed and Aquaculture Environment Control Engineering Techniques Research, Henan Key Laboratory of Farm Animal Breeding and Nutritional Regulation, Zhengzhou 45000

凝集素(Lectin)的生物学功能多样,是一种可以与糖发生特定的和可逆结合的蛋白质[1]。目前大量研究表明,Lectin能起到抗菌和消炎的作用[2-4],并且Lectin和抗菌肽都被定性为免疫因子[5]。Lectin的数量庞大,结构多样,被发现在许多生物体内,包括微生物,植物和动物[6]。根据其结构和功能特征可以把凝集素分为R型、L型、P型、C型、I型和S型等多种类型[7]。

C型凝集素(C-type lectin)代表一个识别碳水化合物配体依赖于钙离子(Ca2+)参与的糖原结合蛋白家族,含有一个或多个一级结构和二级结构同源的碳水化合物识别结构域[8-9],是内吞作用的受体,主要表达在巨噬细胞和内皮细胞。C-type lectin能识别大量的糖基质配体,其在细菌,真菌,病毒感染的细胞,和寄生虫里都有发现[10]。同时C-type lectin在免疫方面也发挥重要的作用,如C-type lectin能识别多种致病菌并且诱导细胞因子的分泌[11]。目前,已经有1 000多个C-type lectin被相继鉴定。

家蝇(Musca domestica L.)普遍存在并且携带至少100种人类和动物疾病[12],然而他们能快速繁殖生长且自身不会引起疾病感染,所以家蝇必定具有完善而高效的免疫防御机制,是人们研究天然抗炎物质的重要资源。家蝇Lsa(NCBI序列号:XP_00-5178145)(lectin subunit alpha)蛋白,有181个氨基酸,其中29到146位编码C-type lectin(CTL)/C-type lectin-like(CTLD)。然而,目前国内外对于家蝇Lsa蛋白抗炎活性及其细胞通路的研究还较少。

试验旨在研究家蝇Lsa蛋白在金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus)刺激下的抗炎活性。首先扩增Lsa基因,构建在pLEX载体上,制备成慢病毒后,稳定转染到RAW264.7细胞中,并通过转染PLEX载体作为阴性对照,通过S. aureus刺激细胞后,收集不同时间点细胞及其上清,对不同时间点细胞提取RNA,反转录后用实时定量PCR的方法检测TNF-α、IL-1β、NF-κB-1、NF-κB-2的mRNA相对转录水平,通过ELISA检测细胞上清中的TNF-α和IL-1β,通过与阴性对照细胞相比,分析家蝇Lsa蛋白的抗炎活性。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 载体、菌种及细胞家蝇幼虫由河南省疾病控制中心提供;pMD20-T载体购自TaKaRa公司;pLEX慢病毒表达载体及其包装质粒(psPAX2)和包膜质粒(pMD2.G)购自GE公司;DH5α感受态细胞购自北京天根公司;用于生产慢病毒的293T细胞和RAW264.7细胞购自ATCC公司;ELISA试剂盒购自达科为公司;S. aureus ATCC 25923购自ATCC公司。

1.1.2 主要试剂和培养基限制酶Xho Ⅰ和Age Ⅰ购自Thermo公司,Trizol试剂和LipofectamineTM 2000试剂购自Invitrogen公司,聚凝胺(Polybrene)和嘌呤霉素(Puromycin)试剂购自SIGMA公司,DMEM培养基和Opti-MEM®培养基购自Gibco公司,胎牛血清购自SeraPro公司,HA抗体购自北京天根公司,荧光二抗购自LI-COR公司,SYBR Premix Ex Taq购自TaKaRa公司,其他试剂均为国产分析纯。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 RNA提取及cDNA合成家蝇三龄幼虫充分研磨后,参照Invitrogen公司的TRIzol®Reagent(Cat.No:15596-018)说明书并做适当改进操作。随后取2 μL进行1%凝胶电泳检测RNA的完整性,随后用核酸定量仪分别测定样品在260 nm,280 nm波长上的光密度,初步估算RNA的纯度和浓度。检测结果良好后,取1 μg总RNA反转录合成cDNA。

1.2.2 Lectin subunit alpha基因表达载体的克隆与构建根据家蝇Lsa基因的mRNA序列信息(XM_005178088.3),设计基因引物,引物分别引入Xho Ⅰ和Age Ⅰ酶切位点,下划线部分为HA标签序列(表 1)。以家蝇幼虫cDNA为模板,进行PCR扩增,PCR反应条件为:95℃预变性5 min;95℃变性30 s,65℃(降低2℃/2循环)退火40 s以及72℃延伸100 s,共16个循环;然后95℃变性30 s,51℃退火40 s以及72℃延伸100 s共19个循环;最后72℃延伸5 min,琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测。PCR产物和pLEX载体用Xho Ⅰ和Age Ⅰ双酶切,连接转化到DH5α感受态细胞中。酶切和测序验证正确的重组质粒命名为pLEX-Lsa。

使用LipofectamineTM 2000转染pLEX-Lsa到293T细胞中。接种293T细胞于10-cm细胞培养皿中,并且在含10%胎牛血清的DMEM培养基中培养,直到细胞生长到汇合度达到70%-80%。稀释12 µg pLEX-Lsa,9 µg的包装质粒(psPAX2)和3.5 µg的包膜质粒(pMD2.G)在1.5 mL Opti-MEM®培养基中,轻轻混匀。LipofectamineTM 2000在使用前混匀,然后添加50 µL LipofectamineTM 2000到1.5 mL Opti-MEM®培养基中。室温孵育5 min后,混匀含pLEX-Lsa培养基和含LipofectamineTM 2000培养基(总体积3 mL),之后室温孵育20 min。添加到293T细胞中,4 h更换新鲜培养基,24 h后收获含病毒的细胞培养上清,分装保存于-70℃备用。以上述同样的方法生产包含空pLEX载体的慢病毒。

1.2.4 重组慢病毒转染RAW264.7细胞在六孔板中培养RAW264.7细胞,在感染日达到60-70%的汇合度。重组慢病毒与新鲜培养基各1 mL,同时加入聚凝胺(Polybrene)2 µg,到RAW264.7细胞中。24 h后更换新鲜培养基继续培养24 h。添加嘌呤霉素(Puromycin)到RAW264.7细胞中,通过不同浓度的不断筛选,且终浓度为4 μg/mL,获得稳定转染的包含pLEX-Lsa的RAW264.7细胞,被命名为RAW-pLEX-Lsa;包含空pLEX载体的RAW264.7细胞,被命名为RAW-pLEX,作为阴性对照。

1.2.5 Western blot分析分别收集RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞,裂解后取40 µg的总蛋白按文献[13]进行Western blotting分析。40 µg总蛋白被分离通过SDS-PAGE电泳,然后被转移到硝酸纤维素膜(NC膜),并将其与电转装置配套的海绵垫放到转移缓冲液中平衡10 min。NC膜被封闭液封闭2 h,一抗为小鼠源Anti-HA antibody,在室温下孵育1-2 h,二抗为荧光素标记羊抗鼠IgG,室温下孵育1 h。

1.2.6 S. aureus刺激RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞在六孔板中分别培养RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞。在37℃的LB中孵育S. aureus,生长到对数期收集菌液。通过梯度稀释和平板涂布的方法检测S. aureus的活菌数。S. aureus刺激RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞,MOI为10:1(细菌:细胞)。分别收集未刺激和刺激3 h,6 h,12 h和24 h细胞,且收集未刺激和刺激6 h细胞上清,在每个时间点分别设置两个平行样品。

1.2.7 RT-PCR标准曲线的制备使用绝对定量法构建标准曲线,对S. aureus刺激的RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞的基因mRNA表达水平进行定量分析。根据小鼠(Mus musculus)NCBI序列信息,分别设计相应的跨内含子引物。小鼠TNF-α基因有两个转录剪接体,分别设计引物,命名为TNF-α-tv-1(NCBI序列号:NM_013693.3)和TNF-α-tv-2(NCBI序列号:NM_001278601.1)。小鼠IL-1β基因有两个转录剪接体,分别是IL-1β和IL-1β-X1,分别设计两个引物,其中一个能体现两个转录剪接体总的mRNA表达水平,另外一个是IL-1β转录剪接体的引物,分别命名为IL-1β-T(NCBI序列号:XM_006498795.3)和IL-1β(NCBI序列号:NM_008361.4)。小鼠NFκB-1(NCBI序列号:NM_008689),NFκB-2(NCBI序列号:XM_006526743.3)和GAPDH(NCBI序列号:NM_008084.3)基因,分别设计引物。所有引物序列见表 1。

1.2.8 RNA的提取及实时定量RT-PCR用Trizol提取RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞总mRNA,取1 μg总RNA反转录合成cDNA,取2 µL cDNA进行实时定量RT-PCR,GAPDH基因为内参基因。反应体系:cDNA 2 µL;SYBR Premix Ex Taq 5 µL;上下游引物(10 pmol/L)各1 µL;无RNA酶超纯水补至10 µL。反应程序为:95℃ 10 min,45个循环:95℃ 10 s,58℃ 30 s,72℃ 30 s。溶解曲线:95℃ 10 s,65℃ 60 s,97℃ 1 s,降温至37℃ 30 s。每个样本重复3次。

1.2.9 ELISA检测细胞炎性细胞因子的蛋白水平分别用TNF-α和IL-1β的ELISA试剂盒,检测未刺激和S. aureus刺激6 h后细胞上清中TNF-α和IL-1β的蛋白水平,用酶标仪读取数值。

1.2.10 统计分析使用SPSS 22软件对数据进行单因素方差分析(One-way ANOVA)和邓肯检验(Duncana test)。

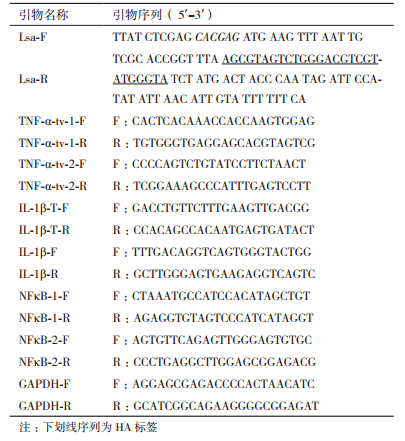

2 结果 2.1 Western blotting的检测结果通过HA抗体进行Western blotting分析,检测Lsa在RAW264.7细胞中的表达。结果(图 1)显示,有特异性条带在21 kD标准分子量附近,表明Lsa在RAW264.7细胞中稳定表达。

|

| 图 1 Western blotting检测蛋白Lsa的表达 A:Western blotting检测Lsa蛋白;B:Western blotting检测β-actin蛋白,大小为43 kD |

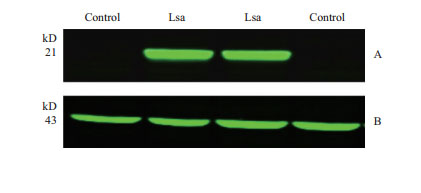

在S. aureus刺激后,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中,TNF-α-tv-1和TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平均迅速升高,6 h达到最高峰,随后下降。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平在6 h相比RAW-pLEX细胞显著下调(P<0.05)。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平在12 h相比RAW-pLEX细胞明显低于RAW-pLEX细胞(P>0.05)。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平在6 h和12 h相比RAW-pLEX细胞显著下调(P<0.05)。随着时间点的变化,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中TNF-α-tv-1和TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平趋势都基本一致。在RAW-pLEX细胞中,TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平在6 h是TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平的45倍,此时与其他各个时间点相对转录水平相比,TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平是TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平的最小倍数。在RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中,TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平在3 h是TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平的57倍,此时与其他各个时间点相对转录水平相比,TNF-α-tv-1基因的相对转录水平是TNF-α-tv-2基因的相对转录水平最小倍数(图 2-A、B)。在S. aureus刺激6 h后,ELISA检测细胞上清中TNF-α蛋白水平,RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞上清中的TNF-α蛋白水平显著低于RAW-pLEX细胞上清中的TNF-α蛋白水平(P<0.05)(图 2-C)。

|

| 图 2 S. aureus刺激前后RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中TNF-α-tv-1(A)和TNF-α-tv-2(B)的mRNA的表达量和TNF-α(C)的产量 A:TNF-α-tv-1的mRNA的表达量;B:TNF-α-tv-2的mRNA的表达量;C:细胞上清中TNF-α蛋白水平(*P<0.05. Untreated:S. aureus没有刺激细胞) |

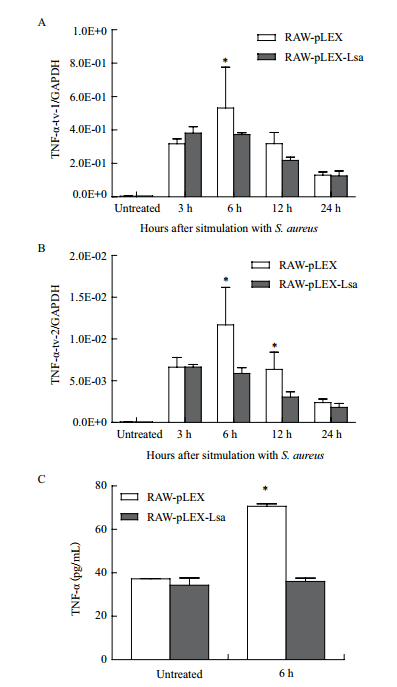

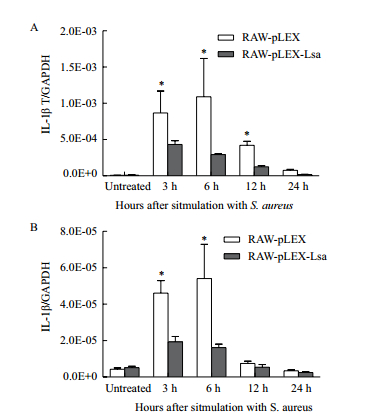

在S. aureus刺激后,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中IL-1βT和IL-1β基因的相对转录水平均迅速升高,6 h达到最高峰,随后下降。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中IL-1βT基因的相对转录水平在3 h,6 h和12 h相比RAW-pLEX细胞显著下调(P<0.05)。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中IL-1β基因的相对转录水平在3 h和6 h相比RAW-pLEX细胞显著降低(P<0.05)。随着时间点的变化,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中IL-1βT和IL-1β基因的相对转录水平趋势都基本一致。在RAW-pLEX细胞中,IL-1βT基因的相对转录水平在3 h,6 h和12 h分别是IL-1β基因的相对转录水平的19,20,57倍。在RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中,IL-1βT基因的相对转录水平在3 h,6 h和12 h分别是IL-1β基因的相对转录水平的22,18,23倍(图 3)。ELISA检测细胞上清中IL-1β的蛋白水平,在RAW-pLEX细胞上清中,S. aureus刺激6 h后,上清中IL-1β的蛋白水平为46 pg/mL,未刺激的细胞上清中IL-1β的蛋白水平未检测到;RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞上清中,IL-1β的蛋白水平在刺激前和刺激后均未检测到。

|

| 图 3 S. aureus刺激前后RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中IL-1βT和IL-1β的mRNA的表达量 A:IL-1βT的mRNA的表达量;B:IL-1β的mRNA的表达量(*P<0.05. Untreated:S. aureus没有刺激细胞) |

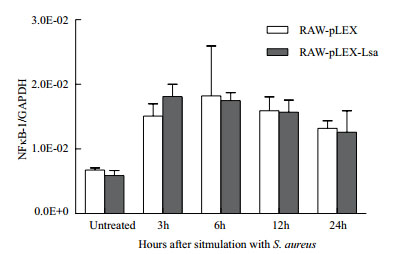

在S. aureus刺激后,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中NFκB-1基因的相对转录水平均迅速升高,6 h达到最高峰,随后下降。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中NFκB-1基因的相对转录水平在各个时间点与RAW-pLEX细胞相比无显著差别(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 S. aureus刺激前后RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中NFκB-1的mRNA的表达量 *P<0.05. Untreated:S. aureus没有刺激细胞 |

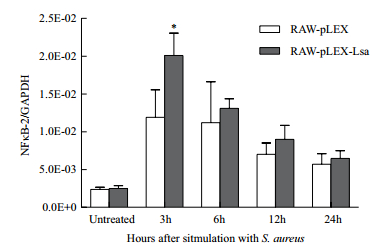

在S. aureus刺激后,RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中NFκB-2基因的相对转录水平均迅速升高,3 h达到最高峰,随后下降。RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中NFκB-2基因的相对转录水平在3 h与RAW-pLEX细胞相比显著升高(P<0.05)(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 S. aureus刺激前后RAW-pLEX-Lsa和RAW-pLEX细胞中NFκB-2的mRNA的表达量 *P<0.05. Untreated:S. aureus没有刺激细胞 |

Dr. Alexander Ogston发现S. aureus是重要的革兰氏阳性菌[14],并且能引起许多疾病。例如,皮肤及软组织感染(SSTIs),肺炎,菌血症,乳腺炎等[15-16]。另外S. aureus感染还会导致严重和持久的宿主炎症反应[17-20]。S. aureus刺激巨噬细胞会引起炎性细胞因子的分泌(包括TNF-a和IL-1β)[21-23],而在免疫效应细胞消除感染的第一阶段炎性细胞因子有利于消除感染[24-25],并且S. aureus刺激巨噬细胞能激活NF-κB信号通路[26]。

炎症是临床常见的病理过程,是机体对损伤因子的病理性防卫反应,也是最重要的保护性反应。高表达量的炎性细胞因子是炎性病变的重要特征之一[27]。TNF-α参与激活中性粒细胞,损伤内皮细胞,和加剧炎症级联反应[28-29]。根据NCBI上的小鼠基因序列信息发现TNF-α有两个转录剪接体。转录剪接体2与转录剪接体1相比,缺少外显子3片段,有48个碱基,16个氨基酸。由图 2可知,在S. aureus刺激RAW264.7细胞引起的炎症反应中,TNF-α-tv-1可能起到更重要的作用。在调节S. aureus引起的宿主免疫反应中,IL-1β是重要的促炎性细胞因子[30]。根据NCBI上的小鼠基因序列信息发现IL-1β有转录剪接体IL-1β-X1和IL-1β。IL-1β与IL-1β-X1相比,外显子缺少1 302个碱基,434个氨基酸。由图 3可知,在S. aureus刺激RAW264.7细胞引起的炎症反应中,IL-1β-X1可能起到更重要的作用。根据我们所查文献,小鼠TNF-α和IL-1β转录剪接体的生物学功能,目前还未见报道。由图 2可知,在S. aureus刺激6 h后,RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞上清中,TNF-α的蛋白水平显著降低。在S. aureus刺激6 h后,ELISA检测细胞上清中IL-1β的蛋白水平,在RAW-pLEX细胞上清中IL-1β的蛋白水平为46 pg/ml,RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞上清中,IL-1β的蛋白水平未检测到。结果表明,在RAW264.7细胞中稳定转染的家蝇Lsa蛋白能够抑制TNF-α和IL-1β的转录和生产。

研究报道,N-乙酰氨基葡萄糖lectin拥有抗炎活性,能减少由炎症引起的TNF-α的表达量[31]。Shan等[32]在2013年发现,小肠黏液包含galectin-3,Dectin-1和FcgRⅡB,可以抑制NFκB调节的促炎因子基因的表达。Freitas等[33]发现酵母聚糖诱导的颞下颌关节组织和三叉神经节中,秋葵(Abelmoschus esculentus)Lectin可以减少TNF-a和IL-1β的表达量。Jin等[34]发现一个新型的的肽(GC31),来自血栓调节蛋白的C型凝集素样结构域,在RAW264.7细胞中发挥抗炎性能通过阻塞LPS激活的NFκB信号通路,进而抑制TNF-a和IL-6的表达。Matsumoto等[35]发现可溶性唾液酸结合免疫球蛋白型凝集素9(sSiglec-9)通过抑制NFκB信号通路的活性,进而减少促炎性细胞因子(TNF-a和IL-6)的表达。在S. aureus刺激后,RAW-pLEX与RAW-pLEX-Lsa相比,RAW-pLEX-Lsa细胞中TNF-α和IL-1β基因的相对转录水平显著下降,而NFκB-1与NFκB-2基因的相对转录水平并没有呈现下降趋势。因此,我们认为在RAW264.7细胞中稳定转染的家蝇Lsa蛋白并不是通过抑制NFκB信号通路的活性,进而显著地抑制TNF-α和IL-1β的转录和生产,而可能是通过其他通路影响炎性细胞因子的表达。

4 结论家蝇Lsa蛋白可以有效地发挥抗炎活性,抑制TNF-α和IL-1β的表达。

| [1] |

Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJ. Lectins as plant defense proteins[J]. Plant physiology, 1995, 109(2): 347-352. DOI:10.1104/pp.109.2.347 |

| [2] |

Barbosa PSF, Martins AMC, Toyama MH, et al. Purification and biological effects of a C-type lectin isolated from Bothrops moojeni[J]. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases, 2010, 16(3): 493-504. DOI:10.1590/S1678-91992010000300016 |

| [3] |

Nunes ES, de Souza MA, Vaz AF, et al. Purification of a lectin with antibacterial activity from Bothrops leucurus snake venom[J]. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology Part B Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, 2011, 159(1): 57-63. |

| [4] |

Soares GDSF, Assreuy AMS, Gadelha CADA, et al. Purification and biological activities of Abelmoschus esculentus, Seed Lectin[J]. The Protein Journal, 2012, 31(8): 674-680. DOI:10.1007/s10930-012-9447-0 |

| [5] |

Liu F, Tang T, Sun L, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of the housefly(Musca domestica)larva using massively parallel pyrosequencing[J]. Mol Biol Rep, 2012, 39(2): 1927-1934. DOI:10.1007/s11033-011-0939-3 |

| [6] |

Utarabhand P, Rittidach W, Paijit N. Bacterial agglutination by sialic acid-specific lectin in the hemolymph of the banana shrimp, Penaeus(Fenneropenaeus)merguiensis[J]. Sci Asia, 2007, 33: 41-46. DOI:10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2007.33.041 |

| [7] |

Zelensky AN, Gready JE. The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily[J]. Febs Journal, 2005, 272(24): 6179-6217. DOI:10.1111/EJB.2005.272.issue-24 |

| [8] |

Drickamer K. C-type lectin-like domains[J]. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 1999, 9(5): 585-590. DOI:10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00009-3 |

| [9] |

Drickamer K. Evolution of Ca2+-dependent animal lectins[J]. Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology, 1993, 45: 207-232. DOI:10.1016/S0079-6603(08)60870-3 |

| [10] |

Graham LM, Gupta V, Schafer G, et al. The C-type lectin receptor CLECSF8(CLEC4D)is expressed by myeloid cells and triggers cellular activation through Syk kinase[J]. J Biol Chem, 2012, 287(31): 25964-25974. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112.384164 |

| [11] |

Dambuza IM, Brown GD. C-type lectins in immunity:recent developments[J]. Current Opinion in Immunology, 2015, 32: 21-27. DOI:10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.002 |

| [12] |

Greenberg B. Flies and disease[J]. Scientific American, 1965, 213: 92-99. DOI:10.1038/scientificamerican0765-92 |

| [13] |

Zhang Y, Wu S, Lv J, et al. Peste des petits ruminants virus exploits cellular autophagy machinery for replication[J]. Virology, 2013, 437(1): 28-38. DOI:10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.011 |

| [14] |

Ogston A. On abscesses[J]. Review of Infectious Diseases, 1984, 6(1): 122-128. DOI:10.1093/clinids/6.1.122 |

| [15] |

Uhlemann AC. Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Case Studies[J]. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2014, 1085: 25-69. DOI:10.1007/978-1-62703-664-1 |

| [16] |

Ferrer M, Difrancesco LF, Liapikou A, et al. Polymicrobial intensive care unit-acquired pneumonia:prevalence, microbiology and outcome[J]. Critical Care, 2015, 19(1): 450. DOI:10.1186/s13054-015-1165-5 |

| [17] |

Wardenburg JB. Panton-valentine leukocidin is not a virulence determinant in murine models of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease[J]. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2008, 198(8): 1166-1170. DOI:10.1086/593348 |

| [18] |

Fast DJ, Schlievert PM, Nelson RD. Toxic shock syndrome-associated staphylococcal and streptococcal pyrogenic toxins are potent inducers of tumor necrosis factor production[J]. Infection & Immunity, 1989, 57(1): 291-294. |

| [19] |

Gillet Y, Issartel B, Vanhems P, et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients[J]. Lancet(London, England), 2002, 359(9308): 753-759. |

| [20] |

Voyich JM, Otto M, Mathema B, et al. Is Panton-Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease?[J]. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2006, 194(12): 1761-1770. DOI:10.1086/jid.2006.194.issue-12 |

| [21] |

Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses[J]. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2009, 22(2): 240-273. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00046-08 |

| [22] |

Nau R, Eiffert H. Modulation of release of proinflammatory bacterial compounds by antibacterials:potential impact on course of inflammation and outcome in sepsis and meningitis[J]. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2002, 15(1): 95-110. DOI:10.1128/CMR.15.1.95-110.2002 |

| [23] |

Mukhin AG, Ivanova SA, Knoblach SM, et al. New in vitro model of traumatic neuronal injury:evaluation of secondary injury and glutamate receptor-mediated neurotoxicity[J]. Journal of Neurotrauma, 1997, 14(9): 651-663. DOI:10.1089/neu.1997.14.651 |

| [24] |

Aribi M, Meziane W, Habi S, et al. Macrophage bactericidal activities against Staphylococcus aureus are enhanced in vivo by selenium supplementation in a dose-dependent manner[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(9): e0135515. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0135515 |

| [25] |

Porcherie A, Cunha P, Trotereau A, et al. Repertoire of Escherichia coli agonists sensed by innate immunity receptors of the bovine udder and mammary epithelial cells[J]. Veterinary Research, 2012, 43(1): 14. DOI:10.1186/1297-9716-43-14 |

| [26] |

Zhu F, Yue W, Wang Y. The nuclear factor kappa B(NF-κB)activation is required for phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus, by RAW 264. 7 cells[J]. Experimental Cell Res, 2014, 327(2): 256-263. DOI:10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.04.018 |

| [27] |

Larsen GL, Henson PM. Mediators of inflammation[J]. Annual Review of Immunology, 1983, 1(1): 335-359. DOI:10.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.002003 |

| [28] |

Murdaca G, Spanò F, Contatore M, et al. Infection risk associated with anti-TNF-α agents:a review[J]. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 2015, 14(4): 1-12. DOI:10.1517/14740338.2015.1023500 |

| [29] |

Koca SS, Bahcecioglu IH, Poyrazoglu OK, et al. The Treatment with antibody of TNF-α reduces the inflammation, necrosis and fibrosis in the non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by methionine-and choline-deficient diet[J]. Inflammation, 2008, 31(2): 91-98. DOI:10.1007/s10753-007-9053-z |

| [30] |

Miller LS, Pietras EM, Uricchio LH, et al. Inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1beta is required for neutrophil recruitment against Staphylococcus aureus in vivo[J]. Journal of Immunology, 2007, 179(10): 6933-6942. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6933 |

| [31] |

Pires AF, Rodrigues NVFC, Soares PMG, et al. A novel N-acetyl-glucosamine lectin of Lonchocarpus araripensis attenuates acute cellular inflammation in mice[J]. Inflammation Research, 2016, 65(1): 43-52. DOI:10.1007/s00011-015-0889-7 |

| [32] |

Shan M, Gentile M, Yeiser JR, et al. Mucus enhances gut homeostasis and oral tolerance by delivering immunoregulatory signals[J]. Science, 2013, 342(6157): 447-453. DOI:10.1126/science.1237910 |

| [33] |

Freitas RS, do Val DR, Fernandes MEF, et al. Lectin from Abelmoschus esculentus reduces zymosan-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats via heme oxygenase-1 pathway integrity and tnf-α and il-1β suppression[J]. International Immunopharmacology, 2016, 38: 313-323. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2016.06.012 |

| [34] |

Jin H, Yang X, Liu K, et al. Effects of a novel peptide derived from human thrombomodulin on endotoxin-induced uveitis in vitro and in vivo[J]. FEBS letters, 2011, 585(21): 3457-3464. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.10.002 |

| [35] |

Matsumoto T, Takahashi N, Kojima T, et al. Soluble Siglec-9 suppresses arthritis in a collagen-induced arthritis mouse model and inhibits M1 activation of RAW264[J]. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 2016, 18(1): 133. |