限于合子胚难以通过正常的手段来分离,进而影响研究生长发育过程,可通过被子植物中的体细胞胚的方式来继续研究,因为被子植物的体细胞胚在形态发生阶段与合子胚存在着对应的相似性[1],具有典型的胚胎器官,如胚根、下胚轴和子叶[2],而且较一定阶段的合子胚容易获取。尽管对体细胞胚胎发生最早阶段的发育特征不甚了解,但是随后的体细胞胚胎发育过程与合子胚的前期和后期过程具有密切的联系[3-4],这与前人将拟南芥的不成熟合子胚进行体细胞胚诱导培养来分析影响胚胎发生发育的因素的研究一致。虽然在单子叶和双子叶植物中胚胎的发育阶段不同,但在早期和晚期相似,都具有合子期,球形胚期和成熟胚期。本文重点讨论在植物胚胎发生前期和后期中关键基因的研究进展以及与相关激素的交互作用,有利于提高对胚胎发生分子调控网络的认识,在未来更深入的胚胎发生研究中奠定分子基础。

1 胚胎茎顶端分生组织(Shoot apical meris-tem,SAM)的细胞构造SAM分布于胚胎顶端分生组织的中心区,周围有侧分生组织和花叶原基起源的外围区(图 1)。干细胞群主要集中在SAM的中心区(Central zone,CZ),其多层结构主要由3个不同的克隆细胞层组成,L1和L2层为单层细胞,其平行于表面各自分开,而L3层的细胞能够以随机的方向展开形成肋分生组织(Rib meristem,RM)或组织中心(Organizing center,OC)的多层结构[5]。干细胞分裂增殖的子细胞分别进入侧分生组织分化为形成侧部器官和进入外围区分化为茎或叶原基等。SAM的主要功能是在CZ中维持未分化的多功能干细胞群和未分化的干细胞进入外周区(Peripheral zone,PZ)加快分裂速度分化为器官原基。

2 植物胚胎前后期关键基因 2.1 植物胚胎早期关键基因LEC类基因LEAFY COTYLEDON(LEC)类基因包括LEA-FY COTYLEDON1(LEC1)、LEAFY COTYLEDON 1-LIKE(L1L)、LEAFY COTYLEDON2(LEC2)、FUSCA3(FUS3),前两者编码一种HAP3亚基的CCAAT结合转录因子,后两者编码与B3结构域相关的转录因子。

2.1.1 L1L基因在LEC1和FUS3基因方面蒋文婷[7]已顺述其研究进展,揭示在胚胎发生早期和晚期的正常发育过程中LEC1基因是关键的调节物,能够足以诱导在营养细胞中的胚胎发育。与LEC1最密切相关的亚基L1L共同组成LEC1型的AHAP3亚基,除此之外的AHAP3亚基称之为非LEC1型。虽然在L1L与LEC1同为LEC1型的AHAP3亚基,但有研究指出LIL和LEC1在胚胎发生中的功能又有明显的区别。lec1突变体使得胚胎发生晚期停滞,能够拥有完整的却畸形的子叶和胚轴,而且在胚胎干燥之前可被拯救发育为正常幼苗[8];通过RNAi技术来抑制L1L诱导的胚胎在早期球状期受到阻碍,其早期胚胎不能被拯救来产生正常生长的植物。除此之外,在胚胎发生后的L1L RNA的累积量高于LEC1 RNA,类似于LEC1主要在发育中的种子中检测到,并且即使在突变体种子中检测L1L RNA,其也不能拯救lec1的表型[9]。因此在胚胎发育过程中LIL主要在早期发挥作用,具有从营养阶段的细胞转化为胚发生的能力[10],能够维持早期胚胎发展的进程,LEC1也在早期和LIL功能部分冗余,但是在种子发育晚期LEC1可能发挥重要的作用。L1L可能位于LEC1的上游来共同调节胚胎的发生发育,揭示了LEC1和L1L在胚胎发生中都发挥独特的作用。

2.1.2 LEC2基因有关学者研究[11]与LEC1、L1L同样具有特异性B3结构域的LEC2转录因子发现,它在合子胚和体细胞胚发生中起到核心作用,lec2表型在早期胚胎形成期间出现胚轴形态的缺陷,而且可以在种子成熟前拯救干燥不耐受的种子进而发育完整植株[12];过表达LEC2能诱导体细胞胚的形成[13],而在生长素处理下的培养外植体的胚胎发生受到损害[11]。有关研究揭示了LEC2的活性与施用外源IAA之间关系密切,指出在无IAA条件下培养的外植体中,由于LEC2基因的过表达使得IAA浓度增加满足刺激体细胞胚发生的需要[14]。这就证明了LEC2基因可能通过内生生长素的水平来影响胚胎发生的机制。Wójcikowska等[11]认为体细胞胚的形成与局部生长素的产生相关,LEC2在IPA-YUC生长素合成途径中起到关键作用,其可能活化该途径中YUC(YUC1,YUC2,YUC4,YUC10)来进行信号传导[11, 15],YUCCA蛋白是一种依赖色氨酸的生长素合成的黄素单氧化酶,通过LEC2控制的机制能够在体细胞组织中创造胚胎发生的环境[15]。除此之外,通过极性生长素转运产生的生长素梯度可能也参与触发体细胞胚胎的发生。

2.2 植物胚胎后期关键基因WUS基因WUSCHE(WUS)编码不同于KNOTTED1类的新类别的同源结构域蛋白,产生于茎端分生组织的OC细胞中并调节参与分生组织和细胞分裂相关的许多基因转录的转录因子[16-17],在RM/OC的细胞中表达[18],并在SAM的干细胞下面的一组细胞中表达,以非自发细胞的方式影响干细胞命运而且在茎顶端分生组织、花序分生组织中起到关键作用[19]。当WUS功能受到抑制,SAM表现出严重缺陷[20]。由于启动WUS的表达不依赖SHOOTMERISTEMLESS(STM)的活性,STM是一类KNOTTED1-LIKE HOMEOBOX(KNOX1)基因,在该基因突变的背景下导致SAM不能完整的形成[21],并且WUS基因的表达仅出现在SAM的小亚结构中[22],因此STM和WUS似乎在不同的水平上调节SAM的发育。尽管STM主要作用于中心分生组织细胞使其未分化,但这些细胞的正常功能正是WUS基因所需要的,也证实了STM作用于WUS的上游[23]。由于SAM几乎在整个植物的生命周期中都存在着干细胞群[24],因此茎端分生组织的稳态主要通过控制分生组织中心中缓慢分裂的干细胞以及其移位到外周细胞进而经历细胞分化的平衡[8]。同源结构域转录因子WUS从组织中心到中心区的运动需要维持干细胞稳态[25],WUS和CLAVATA能够以负反馈回路的组成部分来控制这种平衡[26],在这种反馈机制中,最关键的是维持恒定数量的干细胞,WUS转录限制OC细胞自身的水平主要通过在CZ的相邻细胞中激活负调节物CLAVATA3(CLV3),CLV3编码在细胞外空间与CLAVATA1(CLV1)/CLV2结合起作用的小肽,能够通过阻止围绕CZ外周区细胞分化为CZ细胞限制整体SAM的大小,CLV1指的是在RM中一种受体激酶,其富含亮氨酸[27-29],具体的过程是指在OC的细胞中合成的WUS蛋白迁移至CZ中,主要通过绑定至CLV3启动子元件的方式能直接控制其转录激活[18],是WUS蛋白质被转运而非在其mRNA中被检测到,以发挥其功能。与前人做过的研究类似,在玉米的SAM中能检测KNOTTED1(KN1)mRNA,但在SAM的外周细胞和叶基上以及L1层无法积累KN1mRNA,而KN1蛋白存在于L1中[30-31],显示了在mRNA和蛋白质表达结构域之间存在明显差异。而WUS的RNA在CZ下方的L3层细胞形成的RM/OC中的几个细胞被发现[18, 22]。有关研究提出一种模型能够理解WUS-CLV3反馈机制的重要性,其主要包括WUS蛋白直接激活CLV3的转录和从CZ中发出的CLV3信号负反馈WUS来维持干细胞的数量[18]。

同时过表达WUS和STM能够形成异位芽,而其中的单独基因过表达不能产生上述效果[32-33]。由此可见,在胚胎器官发生过程中WUS和STM的组合是至关重要的。又因为PINFORMED(PIN)开始启动之后,WUS和STM表达的时刻可能标志着器官和茎的发生。STM并不像WUS仅在小区域中表达,其分布于整个分生组织。STM在SAM的作用与WUS和CLV相互独立又互补,其抑制干细胞分化来保持不确定的细胞命运[34],而WUS在一定区域扩增干细胞[32, 35],有利于平衡干细胞生长和器官原基的生长。

3 关键基因与相关激素的相互调节作用 3.1 LEC转录因子与植物激素交互作用产生刺激体细胞胚发生的环境有些单独基因如YUC的过表达不能够诱导体细胞胚的发生[36],然而植物激素ABA/GA水平的高低对体细胞胚发生的能力有着至关重要的影响,与ABA信号转导机制相关的重要基因的突变抑制体细胞胚的发生[37],而抑制GA合成途径的相关基因能够促进形成体细胞胚胎[38],由此可知ABA能够促进体细胞胚的发生,GA可能对其具有拮抗作用,这可以在ABA/GA对胡萝卜体细胞胚影响的研究中[39-40]得到进一步的证明。LEC2诱导体细胞胚发生常与GA的合成抑制相关,GA2ox6能够编码使GA生物活性失活的一种酶,常被AGAMOUS-LIKE15(AGL15)激活,它是一种MADS盒转录因子,过表达该基因能够增加体细胞胚发生的能力,而LEC2直接控制AGL15的活性[38]。然而GA生物合成酶基因的突变能够减少体细胞胚的数量,可见在体细胞胚不同阶段对GA的需求不同。与其类似,通过LEC2控制的编码使ABA分解代谢的ABA8’-羟化酶(CYP707A1,CYP707A2,CYP707A3)[41]的激活来降低ABA水平进而诱导体细胞胚胎发生[42],而在不成熟合子胚的子叶阶段,通过LEC1或LEC2来激活FUS3进而引起ABA水平的增加[41]有利于胚的成熟,这暗示着ABA的水平与其发生胚的潜力具有正调控的关系[43],在胚胎形成到胚胎成熟时ABA/GA的比例逐渐升高有利于胚胎发生及其发育,到器官发生时期其比例急剧下降来完成完整的生命周期。

除上述激素之外,过表达AGL15能够响应植物生长素(AUXIN)增强胚胎发生能力[41],并且LEC2具有快速增强AUXIN启动子活性的特性[42],使得由LEC2控制表达的组织能够响应生长素信号进行体细胞胚的诱导。又或许是通过LEC2激活IAA30[41],IAA30可以编码一种生长素信号蛋白,来提高游离生长素的浓度或者刺激组织中细胞对生长素的反应,在AUXIN信号转导途径中启动体细胞胚的发生。

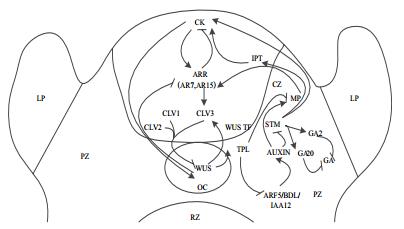

3.2 植物激素参与胚胎发育中SAM的调控植物激素参与控制胚胎发生的研究表明,AUXIN和细胞分裂素(Cytokinin,CK)对植物胚胎SAM的形成和维持具有重要的调节作用。除了下调STM基因的表达之外,与其他信号与STM共同参与使得SAM外围区域的AUXIN达到阙值的过程,并且能够调节SAM中的外围区域向器官发生的转变[44-46]。前人[47]已经探讨出分裂和维持未分化的干细胞与在SAM中心区域高水平的CK的活性相关。CK在幼芽组织[48]和芽再生期间[49]诱导植物生长素的生物合成进而促进建立生长素梯度。相反,由于STM基因的表达能促进CK的生物合成,AUXIN通过抑制STM基因的表达来控制CK的水平[50-51]。这两种激素相互抑制达到体内平衡,防止任意一激素过多影响干细胞的维持发展及器官发生畸变。响应于IAA的因子如(AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 3 / MONOPTEROS)ARF3、MP / ARF5和A型ARR ARR7和ARR15[49, 52],对于CK的分布范围由AUXIN通过异戊烯基转移酶(IPT)来负反馈调节;然而,TOPLESS(TPL)[53]由CK诱导的WUS基因激活,通过与IAA12 / BODENLOS(IAA12 / BDL)和MONOPTEROS /AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 5(MP / ARF5)的相互作用减少AUXIN信号传导[54-55],在这生长素转导途径中TPL作为一种转录共抑制子来调节植物生长发育。除此之外,KONX转录因子与CK和赤霉素GA交联并对器官的发生起到平衡的作用[56],能够刺激CK的积累维持干细胞的分裂,以及抑制SAM中的CK来阻止干细胞的分化[47]。CK的积累主要是由于在细胞分裂素合成中起重要作用的异戊烯基转移酶(IPT)基因被分生组织CZ中的KNOX直接激活,在KNOX发生突变的表型上CK信号受到严重阻碍[51, 57],而WUS直接抑制CK诱导的应答调节剂ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR(ARR)(ARR7,ARR15),其也可通过MP介导的AUXIN信号转导途径来受到抑制[52],使得CK非常精确地刺激SAM中干细胞的分裂[58]。对于GA的控制是由KONXI基因直接抑制GA生物合成基因GA20氧化酶和刺激GA2氧化酶的表达,能够在SAM的顶端抑制GA20的表达并且促进叶原基基部的GA20的表达使得GA转化为无活性的GA,仅有限的GA发挥作用[47, 59-60]。由此可见KNOXI转录因子对于分生组织功能来说是必需的,其可以通过诱导局部的CK合成发挥作用,作为一种中枢调节剂调节分生组织中的激素水平[61]。

在参与有关SAM形成的基因中,如STM和CLV1基因的表达上调大约处于发芽期,而WUS稍早上调,响应于细胞分裂素,其在SAM的中心区的组织中心表达[62],继而转移至覆盖的干细胞,通过WUS和CLAVATA的反馈机制维持组织和器官发展,在这其中WUS能够直接诱导CLAVATA3(CLV3)表达,而CLV编码一种信号肽能够限制WUS到组织中心细胞表达,其诱导上调导致下调WUS和限制CZ结构域的发展[63]。clv3突变体表现出过高的WUS表达量造成臃肿的SAM以及过表达CLV3导致SAM终止的现象[22, 64-65]表明CLV3能够抑制WUS的表达,并且能形成负反馈环[18]。

对于调节SAM的信号网络是由许多调节子和信号转导途径组成,独立于WUS基因表达的KNOX途径与激素具有交互作用,能够维持高浓度的CK和低浓度的GA的环境来确保正确的SAM功能,而响应于CK的WUS-CLV途径对于维护SAM是必要的的中心反馈回路,能够持续产生干细胞进而促进侧向器官生长,这两种途径对于维持SAM中的平衡器官原基的生长和干细胞持续产生是不可缺少的。对于其信号转导途径可归纳为图 2。

|

| 图 2 SAM中相关基因与激素之间的相互调控 |

综述以上植物胚胎发生前后期的机制,揭示了LEC类基因与植物激素在创造体细胞胚发生的环境中的重要作用,以及SAM的关键基因与植物激素相互作用共同维持和调节胚胎后期的发展,但是胚胎发生前期的一些基因及其功能还未得到验证,其与植物激素的相互调节有待进一步的研究,启动胚胎发生前期WUS和STM基因是否与LEC类基因交集还需考证。尽管在胚胎后期的研究较为详细,但是激素与基因之间相互作用而发挥功能的方式还需要进一步解析。

| [1] |

Suárez MF, Suárez MF, Botanik HC. Plant embryogenesis[J]. Methods in Molecular Biology, 2008, 427(1997): 535-576. |

| [2] |

Arnold SV, Sabala I, Bozhkov P, et al. Developmental pathways of somatic embryogenesis[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 2002, 69(3): 233-249. DOI:10.1023/A:1015673200621 |

| [3] |

Elhiti M, Stasolla C. Somatic embryogenesis:The molecular network regulating embryo formation[M]. New Delhi: Springer India, 2016.

|

| [4] |

Hübers M, Kerp H, Schneider JW, et al. Dispersed plant mesofossils from the middle Mississippian of eastern Germany:Bryophytes, pteridophytes and gymnosperms[J]. Review of Palaeobotany & Palynology, 2013, 193(3): 38-56. |

| [5] |

Rieu I, Laux T. Signaling pathways maintaining stem cells at the plant shoot apex[J]. Semin Cell Dev Biol, 2009, 20(9): 1083-1088. DOI:10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.09.013 |

| [6] |

Bowman JL, Eshed Y. Formation and maintenance of the shoot apical meristem[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2000, 5(3): 110-115. DOI:10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01569-7 |

| [7] |

蒋文婷, 曾会明. 落地生根胎生苗发育及其相关基因研究进展[J]. 生物技术通报, 2016(7): 13-20. |

| [8] |

Haecker A, Laux T. Cell-cell signaling in the shoot meristem[J]. Current Opinion in Plant Biology, 2001, 4(5): 441. DOI:10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00198-9 |

| [9] |

Kwong RW, Bui AQ, Lee H, et al. Leafy cotyledon1-like defines a class of regulators essential for embryo development[J]. Plant Cell, 2003, 15(1): 5-18. DOI:10.1105/tpc.006973 |

| [10] |

Zhu SP, Wang J, Ye JL, et al. Isolation and characterization of leafy cotyledon 1-like gene related to embryogenic competence in citrus sinensis[J]. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult, 2014, 119(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1007/s11240-014-0509-1 |

| [11] |

Wójcikowska B, Jaskóła K, Gąsiorek P, et al. Leafy cotyledon2(lec2) promotes embryogenic induction in somatic tissues of Arabidopsis, via yucca-mediated auxin biosynthesis[J]. Planta, 2013, 238(3): 425-440. DOI:10.1007/s00425-013-1892-2 |

| [12] |

Meinke DW, Franzmann LH, Nickle TC, et al. Leafy cotyledon mutants of Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, 1994, 6(8): 1049-1064. DOI:10.1105/tpc.6.8.1049 |

| [13] |

Stone SL, Kwong LW, Yee KM, et al. Leafy cotyledon2 encodes a B3 domain transcription factor that induces embryo development[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(20): 11806-11811. DOI:10.1073/pnas.201413498 |

| [14] |

Ledwoń A, Gaj MD. Leafy cotyledon2 gene expression and auxin treatment in relation to embryogenic capacity of Arabidopsis somatic cells[J]. Plant Cell Reports, 2009, 28(11): 1677-1688. DOI:10.1007/s00299-009-0767-2 |

| [15] |

Stone SL, Braybrook SA, Paula SL, et al. Arabidopsis leafy cotyledon2 induces maturation traits and auxin activity:Implications for somatic embryogenesis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2008, 105(8): 3151-3156. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0712364105 |

| [16] |

Yadav RK, Reddy GV. WUSCHEL protein movement and stem cell homeostasis[J]. Plant Signal Behav, 2012, 7(5): 592-594. DOI:10.4161/psb.19793 |

| [17] |

Busch W, Miotk A, Ariel FD, et al. Transcriptional control of a plant stem cell niche[J]. Dev Cell, 2010, 18(5): 841-853. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.012 |

| [18] |

Yadav RK, Perales M, Gruel J, et al. Wuschel protein movement mediates stem cell homeostasis in the Arabidopsis shoot apex[J]. Genes & Development, 2011, 25(19): 2025-2030. |

| [19] |

Cao X, He Z, Guo L, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms are critical for the regulation of wuschel expression in floral meristems[J]. Plant Physiology, 2015, 168(4): 1189-1196. DOI:10.1104/pp.15.00230 |

| [20] |

Han P, Li Q, Zhu YX. Mutation of Arabidopsis bard1 causes meristem defects by failing to confine wuschel expression to the organizing center[J]. Plant Cell, 2008, 20(6): 1482-1493. DOI:10.1105/tpc.108.058867 |

| [21] |

Vollbrecht E, Reiser L, Hake S. Shoot meristem size is dependent on inbred background and presence of the maize homeobox gene, knotted1[J]. Development, 2000, 127(14): 3161. |

| [22] |

Haecker A. Role of wuschel in regulating stem cell fate in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem[J]. Cell, 1999, 95(6): 805-815. |

| [23] |

Endrizzi K, Moussian B, Haecker A, et al. The shoot meristemless gene is required for maintenance of undifferentiated cells in Arabidopsis shoot and floral meristems and acts at a different regulatory level than the meristem genes wuschel and zwille[J]. Plant Journal, 1996, 10(6): 967-979. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-313X.1996.10060967.x |

| [24] |

Weigel D, Jürgens G. Stem cells that make stems[J]. Nature, 2002, 415(6873): 751-754. DOI:10.1038/415751a |

| [25] |

Gabor D, Anna M, Takuya S. A mechanistic framework for noncell autonomous stem cell induction in Arabidopsis[J]. Proc Natil Acad Sci, 2014, 111(40): 14619-14624. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1406446111 |

| [26] |

Schoof H, Lenhard M, et al. The stem cell population of Arabidopsis shoot meristems in maintained by a regulatory loop between the clavata and wuschel genes[J]. Cell, 2000, 100(6): 635-644. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80700-X |

| [27] |

Fletcher JC, Brand U, Running MP, et al. Signaling of cell fate dec-isions by clavata3 in Arabidopsis shoot meristems[J]. Science, 1999, 283(5409): 1911-1914. DOI:10.1126/science.283.5409.1911 |

| [28] |

Kondo T, Sawa S, Kinoshita A, et al. A plant peptide encoded by clv3 identified by in situ maldi-tof ms analysis[J]. Science, 2006, 313(5788): 845-848. DOI:10.1126/science.1128439 |

| [29] |

Ogawa M, Shinohara H, Sakagami Y, et al. Arabidopsis CLV3 peptide directly binds CLV1 ectodomain[J]. Science, 2008, 319(5861): 294. DOI:10.1126/science.1150083 |

| [30] |

Lucas WJ, Bouchépillon S, Jackson DP, et al. Selective trafficking of knotted1 homeodomain protein and its mrna through plasmodesmata[J]. Science, 1995, 270(270): 1980-1983. |

| [31] |

Jackson D. Double labeling of knotted1 mrna and protein reveals multiple potential sites of protein trafficking in the shoot apex[J]. Plant Physiology, 2002, 129(4): 1423-1429. DOI:10.1104/pp.006049 |

| [32] |

Lenhard M, Jürgens G, Laux T. The wuschel and shootmeristemless genes fulfil complementary roles in Arabidopsis shoot meristem regulation[J]. Development, 2002, 129(13): 3195-3206. |

| [33] |

Gallois JL, Woodward C, Reddy GV, et al. Combined shoot meristemless and wuschel trigger ectopic organogenesis in Arabidopsis[J]. Development, 2002, 129(13): 3207-3217. |

| [34] |

Scofield S, Murray JA. Knox gene function in plant stem cell niches[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2006, 60(6): 929-946. DOI:10.1007/s11103-005-4478-y |

| [35] |

Williams L, Fletcher JC. Stem cell regulation in the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem[J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2005, 8(6): 582-586. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.09.010 |

| [36] |

Zhao Y, Chory J. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis[J]. Science, 2001, 291(5502): 306-309. DOI:10.1126/science.291.5502.306 |

| [37] |

Gaj MD, Trojanowska A, Ujczak A, et al. Hormone-response mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana(L.)heynh impaired in somatic embryogenesis[J]. Plant Growth Regulation, 2006, 49(2): 183-197. |

| [38] |

Wang H, Caruso LV, Downie AB, et al. The embryo mads domain protein agamous-like 15 directly regulates expression of a gene encoding an enzyme involved in gibberellin metabolism[J]. Plant Cell, 2004, 16(5): 1206-1219. DOI:10.1105/tpc.021261 |

| [39] |

Kikuchi A, Sanuki N, Higashi K, et al. Abscisic acid and stress treatment are essential for the acquisition of embryogenic competence by carrot somatic cells[J]. Planta, 2006, 223(4): 637-645. DOI:10.1007/s00425-005-0114-y |

| [40] |

Tokuji Y, Kuriyama K. Involvement of gibberellin and cytokinin in the formation of embryogenic cell clumps in carrot(Daucus carota)[J]. J Plant Physiol, 2003, 160(2): 133-141. DOI:10.1078/0176-1617-00892 |

| [41] |

Braybrook SA, Stone SL, Park S, et al. Genes directly regulated by leafy cotyledon2 provide insight into the control of embryo maturation and somatic embryogenesis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2006, 103(9): 3468-3473. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0511331103 |

| [42] |

Wójcikowska B, Gaj MD. Leafy cotyledon2 -mediated control of the endogenous hormone content:Implications for the induction of somatic embryogenesis in Arabidopsis[J]. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture, 2015, 121(1): 255-258. DOI:10.1007/s11240-014-0689-8 |

| [43] |

Braybrook SA, Harada JJ. LECs go crazy in embryo development[J]. Trends Plant Sci, 2008, 13(12): 624-630. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.09.008 |

| [44] |

Long J, Barton MK. Initiation of axillary and floral meristems in Arabidopsis[J]. Dev Biol, 2000, 218(2): 341-353. DOI:10.1006/dbio.1999.9572 |

| [45] |

Reinhardt D, Kuhlemeier C. Auxin regulates the initiation and radial position of plant lateral organs[J]. Plant Cell, 2000, 12(4): 507-518. DOI:10.1105/tpc.12.4.507 |

| [46] |

Benkova E, Michniewicz M, Sauer M, et al. Local, efflux-dependent auxin gradients as a common module for plant organ formation[J]. Cell, 2003, 115(5): 591-602. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00924-3 |

| [47] |

Veit B. Hormone mediated regulation of the shoot apical meristem[J]. Plant Molecular Biology, 2009, 69(4): 397-408. DOI:10.1007/s11103-008-9396-3 |

| [48] |

Jones B, Gunnerås SA, Petersson SV, et al. Cytokinin regulation of auxin synthesis in Arabidopsis involves a homeostatic feedback loop regulated via auxin and cytokinin signal transduction[J]. Plant Cell, 2010, 22(9): 2956-2969. DOI:10.1105/tpc.110.074856 |

| [49] |

Cheng ZJ, Wang L, Sun W, et al. Pattern of auxin and cytokinin responses for shoot meristem induction results from the regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis by auxin response factor3[J]. Plant Physiology, 2013, 161(1): 240-251. DOI:10.1104/pp.112.203166 |

| [50] |

Heisler MG, Ohno C, Das P, et al. Patterns of auxin transport and gene expression during primordium development revealed by live imaging of the Arabidopsis inflorescence meristem[J]. Current Biology Cb, 2005, 15(21): 1899-1911. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.052 |

| [51] |

Yanai O, Shani E, Dolezal K, et al. Arabidopsis knoxi proteins acti-vate cytokinin biosynthesis[J]. Curr Biol, 2005, 17: 1566-1571. |

| [52] |

Zhong Z, Andersen SU, Ljung K, et al. Hormonal control of the shoot stem-cell niche[J]. Nature, 2010, 465(7301): 1089-1092. DOI:10.1038/nature09126 |

| [53] |

Kieffer M, Stern Y, Cook H, et al. Analysis of the transcription factor wuschel and its functional homologue in antirrhinum reveals a potential mechanism for their roles in meristem maintenance[J]. Plant Cell, 2006, 18(3): 560-573. DOI:10.1105/tpc.105.039107 |

| [54] |

Szemenyei H, Hannon M, Long JA. TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis[J]. Science, 2008, 319(5868): 1384-1386. DOI:10.1126/science.1151461 |

| [55] |

Long JA, Ohno C, Smith ZR, et al. Topless regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis[J]. Science, 2006, 312(5779): 1520. DOI:10.1126/science.1123841 |

| [56] |

Dodsworth S. A diverse and intricate signalling network regulates stem cell fate in the shoot apical meristem[J]. Developmental Biology, 2009, 336(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.031 |

| [57] |

Jasinski S, Piazza P, Craft J, et al. Knox action in Arabidopsis is mediated by coordinate regulation of cytokinin and gibberellin activities[J]. Current Biology Cb, 2005, 15(17): 1560-1565. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.023 |

| [58] |

Leibfried A, To JP, Busch W, et al. Wuschel controls meristem function by direct regulation of cytokinin-inducible response regulators[J]. Nature, 2005, 438(7071): 1172-1175. DOI:10.1038/nature04270 |

| [59] |

Sakamoto T, Kamiya N, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, et al. Knox homeodomain protein directly suppresses the expression of a gibberellin biosynthetic gene in the tobacco shoot apical meristem[J]. Genes & Development, 2001, 15(5): 581-590. |

| [60] |

Kyozuka J. Control of shoot and root meristem function by cytokinin[J]. Curr Opin Plant Biol, 2007, 10(5): 442-446. DOI:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.010 |

| [61] |

Yanai O, Shani E, Dolezal K, et al. Arabidopsis KNOXI proteins activate cytokinin biosynthesis[J]. Curr Biol, 2005, 17: 1566-1571. |

| [62] |

Gordon SP, Chickarmane VS, Ohno C, et al. Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2009, 106(38): 16529-16534. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0908122106 |

| [63] |

Müller R, Borghi L, Kwiatkowska D, et al. Dynamic and compensatory responses of Arabidopsis shoot and floral meristems to clv3 signaling[J]. Plant Cell, 2006, 18(5): 1188-1198. DOI:10.1105/tpc.105.040444 |

| [64] |

Brand U, Fletcher JC, Hobe M, et al. Dependence of stem cell fate in Arabidopsis on a feedback loop regulated by clv3 activity[J]. Science, 2000, 289(5479): 617-619. DOI:10.1126/science.289.5479.617 |

| [65] |

Miwa H, Kinoshita A, Fukuda H, et al. Plant meristems:Clavata3/esr-related signaling in the shoot apical meristem and the root apical meristem[J]. J Plant Res, 2009, 122(1): 31-39. DOI:10.1007/s10265-008-0207-3 |