b. School of Life Science, Yunnan University, Kunming 650091, China;

c. Germplasm Bank of Wild Species, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, China

The genus Panax L. (Araliaceae) is one of the most medicinally important plant in East Asia. It includes seven well-recognized species and one species complex that is disjunctly distributed in East Asia and eastern North America (Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Wen, 1999; Lee and Wen, 2004). Almost every species within this genus has been used as a medicinal herb in East Asia, especially in China (Yang et al., 1988). Because of its considerable medicinal benefits, Panax has been involved in many molecular-based phylogenetic analyses in the past few decades. However, high-resolution and well-supported phylogeny within this genus remain elusive. Phylogenetic analysis relying on ITS, 18S rRNA, and plastid fragments have shown that the genus Panax is a monophyletic group; however, the same approaches have not resolved infra-generic relationships within the clade (Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Wen, 1999; Zhu et al., 2003; Lee and Wen, 2004). Although recent studies have clarified the phylogenetic relationships between Panax trifolius, Panax stipuleanatus, Panax pseudoginseng, Panax notoginseng, and the Panax bipinnatifidus species complex, the phylogenetic relationships between Panax ginseng, Panax japonicus, and Panax quinquefolius remain unresolved (Shi et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2017).

The plastomes of angiosperms are typically circular DNA, consisting of two copies of a large inverted repeat (IR) region separated by a large single-copy (LSC) region and a small single-copy (SSC) region (Raubeson and Jansen, 2005; Wicke et al., 2011). Because plastome sequences show a high level of divergence between species and even populations, these sequences provide valuable information for resolving complex relationships in plants (Moore et al., 2007, 2010; Jansen et al., 2007; Parks et al., 2009). With the advent of second-generation DNA sequencing technologies, plastomes have been widely used in recent years to reconstruct robust phylogenies and to identify species (Nock et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013; Ruhsam et al., 2015; Huang et al., 2016). To date, a total of 27 complete Panax plastomes (Supplementary Table S1) have been sequenced (e.g., Kim and Lee, 2004; Choi et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2015; Han et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Nguyen et al., 2017). These plastid genomic resources provide an opportunity to reconstruct a well-supported phylogeny of this medicinally important genus.

The species P. stipuleanatus (Fig. 1) is restricted to the montane evergreen broad-leaved forests along the border between Vietnam and China in southeast Yunnan province (Xiang and Lowry, 2007). In this region, P. stipuleanatus has been traditionally used as a substitute for P. notoginseng, and its roots are extensively collected and sold in the local markets (Yang et al., 1988). Because of overharvesting, natural populations of Panax stipuleanatas have been markedly reduced. As a result, the species was listed as an endangered species by the Ministry of Environmental Protection of P. R. China in 2013 (http://www.zhb.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201309/t20130912_260061). Available genomic resources for P. stipuleanatus are therefore limited, and little is known about the plastome features of the species.

|

| Fig. 1 The geographic distribution and morphological features of Panax stipuleanatus H. T. Tsai & K. M. Feng. A, geographic distribution; B, aerial part; C, inflorescence; D, fruit; E, rootstock. |

Here, we present the complete plastome of P. stipuleanatus obtained through Illumina sequencing and a reference-guided assembly of de novo contigs. In conjunction with the previously published plastomes, the features of the plastomes among Panax species were compared, including gene content and order. Highly divergent DNA regions offering potential use in further species identification and phylogenetic analysis were also identified. Phylogenetic relationships among Panax species were analyzed with the plastome-based dataset. These results may well broaden our understanding of the evolutionary history of Panax.

2. Materials and methods 2.1. Genome sequencing and assemblyTotal genomic DNA was isolated from the silica-gel-dried leaves of P. stipuleanatus, collected in Maguan County, Yunnan Province, China, using a modified CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle, 1987; Yang et al., 2014). Voucher specimens (JYH-2016, 466) were deposited in the Herbarium of the Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS (KUN). Genomic DNA was randomly fragmented into 400e600 bp with an ultrasonicator. Short-insert (500 bp) paired-end libraries were constructed using the Genomic DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), according to the manufacturer's protocol, and then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 system at BGI (Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). The Illumina raw data were filtered with a NGS QC Toolkit (Patel and Jain, 2012). High-quality reads were assembled into contigs using SPAdes v3.10.1 (Nurk et al., 2013) with its default parameters. The representative plastome sequence contigs were then mapped onto the reference plastome sequence of P. japonicus (Genbank accession number: KX247146) in Bowtie v2.2.6 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) with its default-preset options. Assemblies were then assessed and connected using Bandage (Wick et al., 2015). The validated complete plastome sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table S1).

2.2. Genomic annotation and comparisonThe plastome of P. stipuleanatus was annotated with the online software tool, DOGMA (Wyman et al., 2004), coupled with manual corrections for start and stop codons. All tRNAs were further confirmed by the tRNAscan-SE v1.21 (Schattner et al., 2005). Functional classification of the plastid genes was determined by referring to the online database CpBase (http://chloroplast.ocean.washington.edu/). A circular map of the plastome was drawn in OrganellarGenomeDRAW (Lohse et al., 2007).

Complete plastomes of the P. bipinnatifidus species complex, P. ginseng, P. japonicus, P. notoginseng, Panax quiquefolius, P. trifolius, and Panax vietnamensis were downloaded from NCBI. Multiplesequence alignments were performed with MAFFT software (Katoh et al., 2002), and manually edited where necessary. Geneious v7.0 (Kearse et al., 2012) was used to compare the boundaries of the LSC, IR, and SSC regions among the Panax plastomes. To compare sequence divergence among different Panax plastomes, the mVISTA tool was used (Frazer et al., 2004), with P. ginseng set as the reference. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) occurring across Panax plastomes were identified with the Shuffle-LAGAN model in Geneious v7.0 (Kearse et al., 2012). Divergent percentages of SNPs among the homologous regions across these species were also calulated.

2.3. Synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rate analysisNon-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitutions, and their ratios (Ka/Ks), are important indictors that reflect the plastome evolution and natural selection (Yang and Nielsen, 2000). Protein-coding exons were extracted from the plastomes of the eight Panax taxa and Aralia undulata Handel-Mazzetti. These genes were translated into protein sequences and aligned separately using Geneious v7.0 (Kearse et al., 2012). The Ks and Ka substitution rates for each protein-coding exon were estimated in DnaSP v5.0 software (Librado and Rozas, 2009).

2.4. Phylogenetic analysisAll 28 available plastome sequences of Panax were included in the analysis. A. undulata was used as the outgroup to root the phylogenetic tree. Maximum-likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted based on the following data partitions: (1) the whole plastome; (2) the protein-coding exons (Table S2); (3) the LSC regions; (4) the SSC regions; (5) the IR regions; and (6) the introns and intergenic spacers. All sequences were aligned with the software MAFFT (Katoh et al., 2002). All gaps in the sequence alignment were excluded. For each dataset, the best-fitting partition scheme and nucleotide substitution models were screened in the program PartitionFinder v2.1.1 (Lanfear et al., 2012). For each analysis, the branch lengths were linked, and the models of nucleotide substitution were restricted to RAxML (Stamatakis, 2006); the "greedy" search algorithm was selected. All ML analyses were done in RAxML-HPC BlackBox v8.1.24 software (Stamatakis, 2006). The bootstrap (BS) value for each branch was computed with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

3. Results 3.1. Plastome featuresIn total, we obtained 4, 948, 544 paired-end clean reads for P. stipuleanatus. These reads were used to assemble the P. stipuleanatus plastome. The overall size of the P. stipuleanatus plastome is 156, 069 base pairs (bp), and it shows a typical quadripartite structure, including a pair of IRs (each 25, 887 bp) that divide the genome into LSC (86, 126 bp) and SSC (18, 169 bp) regions (Fig. 2, Table 1). The total length of the coding regions (i.e., proteincoding genes, tRNA genes, and rRNA genes) and non-coding regions (i.e., introns and intergenic spacers) are 91, 632 bp and 64, 437 bp, respectively (Table 1). The plastome of P. stipuleanatus possesses 114 unique genes, including 80 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNAs, and four rRNA genes. Of these, 12 protein-coding genes (atpF, ndhA, ndhB, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2, rpoC1, rps12, rps16, clpP, and ycf3), and six tRNAs (trnA-UGC, trnG-GCC, trnI-GAU, trnK-UUU, trnL-UAA, and trnV-UAC) contain at least one intron (Table 2).

|

| Fig. 2 Plastome map of the Panax stipuleanatus. Genes shown outside of the outer layer circle are transcribed counterclockwise, whereas those genes inside of this circle are transcribed clockwise. The colored bars indicate the known protein-coding genes, tRNA, and rRNA. The dashed, darker gray area of the inner circle denotes the GC content, while the lighter gray area indicates the AT content of the genome. LSC, large single-copy; SSC, small single-copy; IR, inverted repeat. |

| Species | Total | LSC | SSC | IRs | Coding sequence | Non-coding sequence | |||||

| Length (bp) | Length (bp) | Length (bp) | Length (bp) | Length (bp) | Length (bp) | ||||||

| Aralia undulate Handel-Mazzetti | 156, 333 | 86, 028 | 18, 089 | 26, 108 | 92, 417 | 63, 916 | |||||

| Panax bipinnatifidus Seemann species complex | 156, 063 | 86, 111 | 18, 174 | 25, 889 | 91, 632 | 64, 431 | |||||

| Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer | 156, 241-156, 425 | 86, 106-86, 200 | 16, 077-18, 084 | 26, 018-28, 018 | 92, 060-92, 238 | 64, 116-64, 259 | |||||

| Panax japonicus (T. Nees) C. A. Meyer | 156, 188 | 86, 199 | 18, 013 | 25, 988 | 91, 822 | 64, 365 | |||||

| Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F. H. Chen | 156, 324-156, 466 | 86, 082-86, 190 | 18, 004-18, 554 | 25, 861-26, 136 | 91, 866-92, 134 | 64, 202-64, 521 | |||||

| Panax quinquefolius L. | 156, 088-156, 364 | 86, 095-86, 124 | 17, 993-18, 080 | 26, 000-26, 080 | 88, 009-92, 012 | 64, 076-68, 355 | |||||

| Panax stipuleanatus C. T. Tsai & K. M. Feng | 156, 069 | 86, 126 | 18, 169 | 25, 887 | 91, 632 | 64, 437 | |||||

| Panax trifolius L. | 156, 157 | 86, 322 | 18, 047 | 25, 894 | 91, 441 | 64, 716 | |||||

| Panax vietnamensis Ha & Grushv | 155, 992-155, 993 | 86, 177-86, 178 | 17, 935 | 25, 940 | 91, 634-91, 643 | 64, 350-64, 358 |

| Category of Genes | Group of gene | Name of gene |

| Ribosomal RNA genes | rrn4.5×2, rrn5×2, rrn1×2, rrn23×2 | |

| Transfer RNA genes | trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-UCC, trnG-UCC*, trnH-GUG, trnK-UUU*, trnL-UAA*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnPUGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-UGU, trnT-GGU, trnV-UAC*, trnY-GUA, trnW-CCA, trnfM-CAU, trnA-UGC*×2, trnI-CAU×2, trnI-GAU*×2, trnL-CAA×2, trnN-GUU×2, trnR-ACG×2, trnV-GAC×2 | |

| Ribosomal protein (small subunit) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7×2, rps8, rps11, rps12**×2, rps14, rps15, rps16*, rps18, rps19 | |

| Ribosomal protein (large subunit) | rpl2*×2, rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23×2, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 | |

| RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 | |

| Translational initiation factor | infA | |

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem Ⅰ | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, ycf3**, ycf4 |

| Subunits of photosystem Ⅱ | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of cytochrome | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit of Rubisco | rbcL | |

| Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB*×2, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Subunit of acetyl-CoA | accD | |

| Synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| ATP-dependent protease | clpP** | |

| Component of TIC complex | ycf1×2 | |

| Genes of unknown function | Conserved open reading frames | ycf×2, ycf15×2 |

| ×2: Two gene copies in IR regions; *: With one intron; **: With two introns. | ||

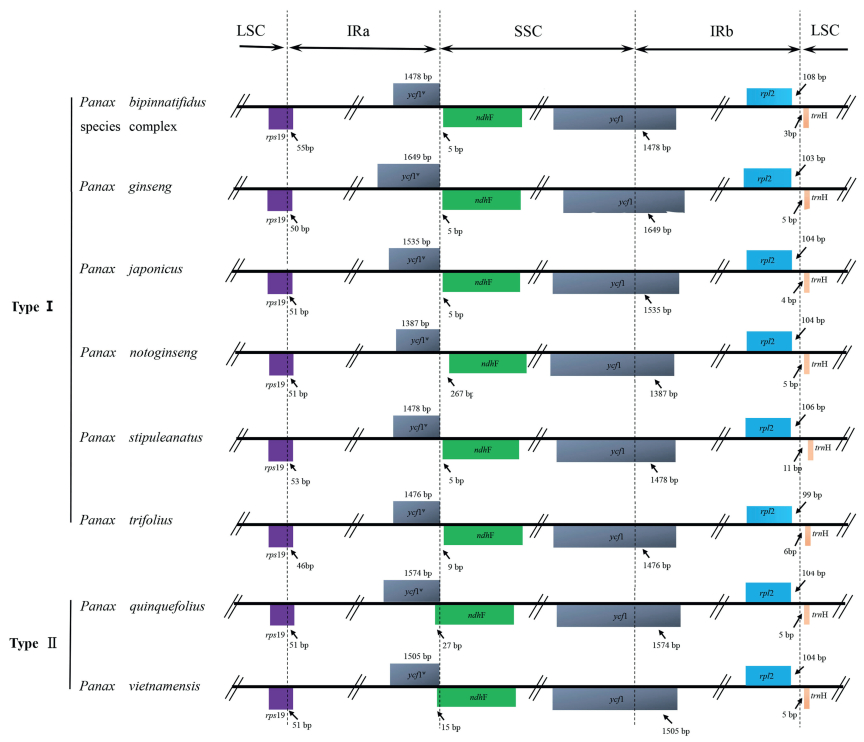

The IRs/LSC and IRs/SSC boundaries among Panax plastomes were compared (Fig. 3). The extensions of the IRs into rps19 and the intergenic spacer between rpl2 and trnH-GUG occur respectively at the IRa/LSC and IRb/LSC boundaries. Although the expansion of the IRs into the ycf1 pseudogene at the IRs/SSC junctions occurred in all species, the overlap between the ycf1 pseudogene and ndhF was only detected in P. quiquefolius and P. vietnamensis.

|

| Fig. 3 Comparison of the borders of the LSC, SSC, and IR regions among the eight Panax plastomes. LSC, large single-copy; SSC, small single-copy; IR, inverted repeat. |

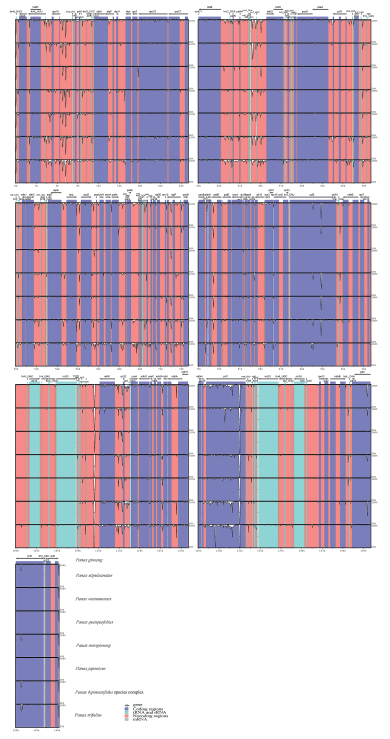

Plastome sequence divergences were identified among the homologous regions across the eight Panax taxa (Fig. 4). We identified 1130 SNPs in the matrix of these plastomes, with average variant frequency of 0.72%. SNP mutations include 743 SNP sites detected in the LSC region, 291 SNPs in the SSC region, and 48 SNPs in the IR region. Their corresponding average variant frequencies were 0.86%, 1.60%, and 0.19%. In addition, 498 SNPs (average variant frequency = 0.62%) were detected in the protein-coding exons, while 620 SNPs (average variant frequency = 0.96%) were detected in the non-coding regions (Table 3). The divergent frequencies of the coding regions ranged from 0.07% to 2.41% (Supplementary Table S3), and those of the non-coding regions ranged from 0.11% up to 5.66% (Supplementary Table S4). According to the sequence divergences, we screened nine protein coding regions-ccsA, matK, ndhF, petL, psaI, rpl22, rpoA, rps3, and ycf1-which showed the percentage of SNPs >1%. We also scanned 10 non-coding regions-atpA-atpF, ccsA-ndhD, infA-rps8, ndhI-ndhA, psbK-psbI, rpl14- rpl16, rpl2-trnH-GUG, rpl22-rps19, rps19-rpl2, and trnY-GUA-trnEUUC-which showed a divergence proportion >3%. These particular plastid DNA regions (19 in all) may be utilized as potential molecular markers to reconstruct the phylogeny of Panax and to identify different species of this genus.

| Data type | Number of SNPs | Characters (bp) | Divergence proportion (%) |

| Complete plastome | 1130 | 156, 069 | 0.7240 |

| Protein-coding genes | 498 | 79, 774 | 0.6243 |

| Non-coding regions | 620 | 64, 437 | 0.9622 |

| LSC region | 743 | 86, 126 | 0.8627 |

| SSC region | 291 | 18, 169 | 1.6016 |

| IR regions | 48 | 25, 887 | 0.1854 |

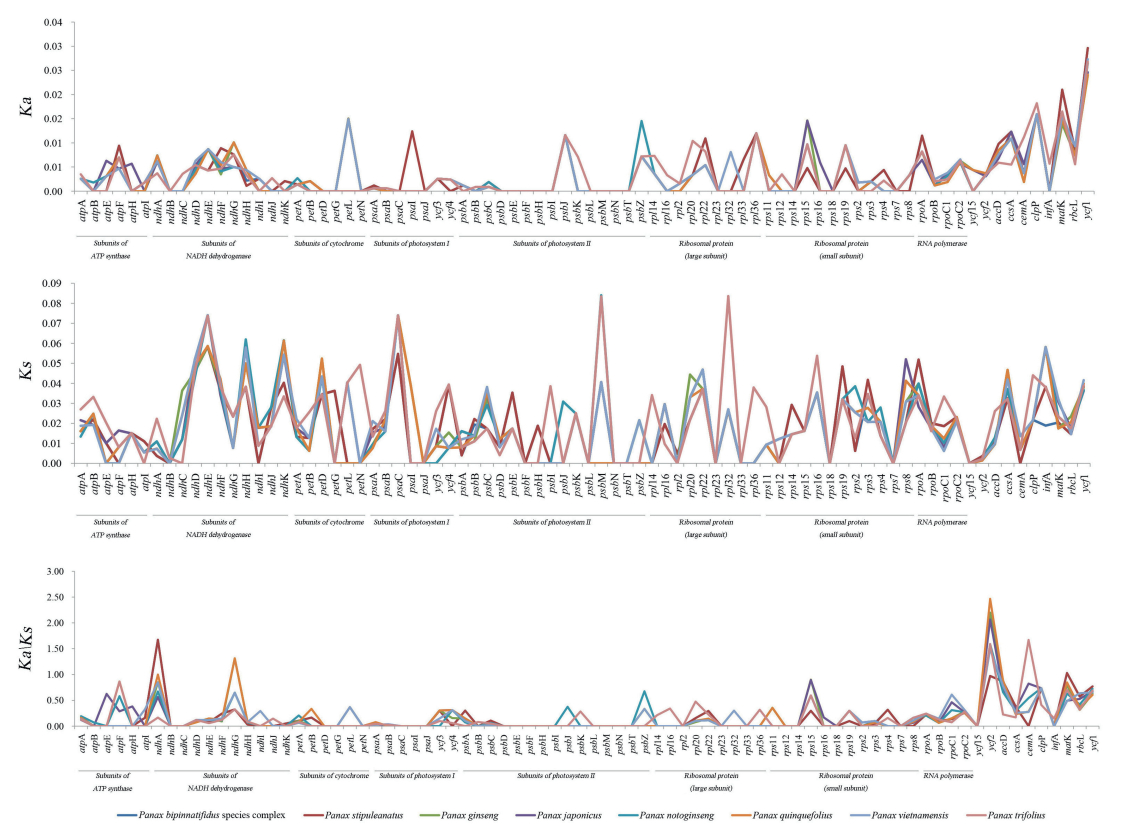

The Ks values of the eight Panax plastomes ranged from 0.0166 to 0.0218, while the Ka values ranged from 0.0032 to 0.0034; the Ka/Ks ratio ranged from 0.1391 to 0.1729 (Table 4, Fig. 5). We identified five genes (i.e., cemA, matK, ndhA, ndhG, and ycf2) with Ka/Ks values greater than one. Three of them (ndhA, ndhG, and ycf2) were identified in P. quinquefolius; one gene (ycf2) was identified in P. japonicus, P. vietnamensis and P. notoginseng; two genes were identified in P. ginseng (ndhG and ycf2), P. stipuleanatus (ndhA and matK), the P. bipinnatifidus species complex (ndhA and matK) and P. trifolius (cemA and ycf2). However, their P-values were greater than 0.05 (Supplementary Table S5), which suggested that no single protein-coding gene in the eight Panax plastomes has yet to be positively selected in a statistically significant way (Yang and Nielsen, 2000).

| Taxa | Non-synonymous (Ka) | Synonymous (Ks) | Ka/Ks |

| Panax bipinnatifidus species complex | 0.0032 ± 0.0006 | 0.0166 ± 0.0018 | 0.1391 |

| Panax ginseng | 0.0032 ± 0.0005 | 0.0185 ± 0.0020 | 0.1575 |

| Panax japonicus | 0.0034 ± 0.0005 | 0.0186 ± 0.0020 | 0.1683 |

| Panax notoginseng | 0.0032 ± 0.0006 | 0.0187 ± 0.0022 | 0.1521 |

| Panax quinquefolius | 0.0032 ± 0.0005 | 0.0177 ± 0.0020 | 0.1729 |

| Panax stipuleanatus | 0.0034 ± 0.0006 | 0.0169 ± 0.0018 | 0.1393 |

| Panax trifolius | 0.0034 ± 0.0005 | 0.0218 ± 0.0022 | 0.1523 |

| Panax vietnamensis | 0.0034 ± 0.0006 | 0.0188 ± 0.0021 | 0.1559 |

| Aralia undulata was used as an outgroup. Data are presented as the means ± standard error. | |||

|

| Fig. 5 Non-synonymous substitution (Ka), synonymous substitution (Ks), and the Ka/Ks values for the Panax plastid protein-coding genes. |

Six data partitions from the 29 plastomes were used to perform phylogenetic reconstruction. The tree topologies for the whole plastome (Fig. 6A), protein-coding exons (Fig. 6B), and SSC (Fig. 6D) were congruent with each other, only differing with regards to support values at the interior nodes. By comparison, the phylogenetic relationships based on the LSC regions (Fig. 6C), IR (Fig. 6E), and introns and intergenic spacers (Fig. 6F) showed many similarities with the results from the other three datasets, except for the positions of P. notoginseng, which clustered into a new branch with P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius. Among the six data partitions, the phylogenetic tree for the protein-coding regions received the highest support for the major branches. As the tree shows (Fig. 6B), the eight Panax species were fully resolved as four, well-supported monophyletic clades. The clade represented only by P. trifolius was placed at the basally branching position. The second clade (BS = 100%) includes P. stipuleanatus and the P. bipinnatifidus species complex. The third clade (BS = 100%) contains P. ginseng and P. quinquefolius. The fourth clade (BS = 100%) consists of P. japonicus, P. vietnamensis, and P. notoginseng, in which the subclade of P. japonicus + P. vietnamensis (BS = 100%) diverged from P. notoginseng. In addition, those taxa (P. ginseng, P. notoginseng, P. quinquefolius, and P. vietnamensis) with more than one plastome currently available, were recovered as well-supported monophyletic lineages in all the datasets.

|

| Fig. 6 Phylogenetic tree reconstruction of the genus Panax via maximum likelihood (ML), based on (A) the whole plastome; (B) the protein-coding exons; (C) the large single-copy (LSC) regions; (D) the small single-copy (SSC) regions; (E) the inverted repeated (IR) regions; and (F) the introns and intergenic spacers. The numbers above the line represent the ML-bootstrap values (1000 replicates). |

We compared the plastome of P. stipuleanatus with that of seven published Panax species. All Panax plastomes shared 114 unique genes (80 protein-coding genes, 30 tRNAs, and four rRNAs) in the same order. Although several previous studies (e.g., Millen et al., 2001; Jansen et al., 2007) have revealed that several proteincoding genes (i.e., accD, ycf1, ycf2, rpl22, rps16, rpl23, infA, and ndhF) have been independently lost over the course of angiosperm evolution, these genes were all identified in the eight Panax plastomes. Additionally, the sequence length of the whole plastome, the LSC, SSC, IRs, coding sequences, and non-coding regions of the eight Panax species were quite similar (Table 1). These results suggest that plastome structure and gene content in the genus Panax are highly conserved.

IR expansions often lead to size variations in the plastomes of angiosperms (e.g., Cosner et al., 1997; Plunkett and Downie, 2000; Chumley et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2018). However, the IRs/LSC junctions of the eight Panax plastomes were highly conserved: the IRb/LSC boundaries were located between the rpl2 and trnH-GUG genes and the IR regions expanded into rps19 at the IRa/LSC junction, which is similar to other genera within the Araliaceae family (Li et al., 2013). This type of IRs/LSC boundary has been detected in Cornales (Yang and Ji, 2017), but it has not yet been observed in any other orders within the asterids clade (Kim and Lee, 2004; Huang et al., 2014; Downie and Jansen, 2015; Stull et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2016). In contrast to the IRs/LSC junctions, the IRs/SSC boundaries among the eight Panax plastomes were slightly variable, which may have contributed to the overall size variations among Panax plastomes.

During the evolutionary history of a certain lineage, environmental change may impose selective pressures that result in adaptive evolution (Yang and Nielsen, 2000). However, when we examined the eight Panax plastomes, we did not observe any signs or evolutionary fingerprints of positive selection in the proteincoding genes at the generic level (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table S5). In addition, the average Ka values for these genomes were relatively low, and their Ka/Ks values were all less than one (Table 4). These results imply that the plastid protein-coding genes of Panax species may have undergone strong purifying selection during their evolution (Yang and Nielsen, 2000).

4.2. Phylogenetic inferencesWe used six datasets (complete plastome, protein-coding exons, LSC, SSC, IRs, and non-coding regions) to reconstruct the phylogeny of Panax. Although earlier studies revealed that both the phylogenetic resolution and the support values of nodes may be considerably improved by more and longer DNA sequences (Rokas and Carroll, 2005; Philippe et al., 2011), our results indicate that the phylogeny based on protein-coding exons generated the highest branch support (BS = 100%, Fig. 6B), even though its sequence length is shorter than that of whole plastomes and LSC regions. Furthermore, our analysis found that non-coding regions across Panax plastomes possessed the highest sequence divergence among the six datasets tested (Table 3), while the phylogeny based on non-coding regions did not have the highest branch support (Fig. 6F). The relatively lower node supports observed in the trees using whole plastomes and LSC regions may be attributed to the faster mutation rates of non-coding regions in the plastome, which, as Wiens (2003) has suggested, produces more evolutionary homoplasy. Accordingly, the protein-coding genes of plastomes can provide accurate information with which to trace the relationships within Panax. Compared to previous single- or multi-locus DNA sequence analyses, our plastid phylogenomic analysis produced higher-resolution nodes, with much higher support values within Panax. Similar findings have been reported in analyses of the plastome-wide protein-coding genes of major flowering plant lineages (Jansen et al., 2007), basal angiosperms (Moore et al., 2007), early diverging eudicots (Moore et al., 2010), commelinid monocots (Barrett et al., 2013), and basal Lamiid orders (Stull et al., 2015).

Phylogenetic analysis using protein-coding exons across the plastome recovered four, well-supported, monophyletic clades within Panax, and the relationships within each clade were also robustly supported (BS = 100%, Fig. 6B), which enabled the phylogenetic backbone of this genus to be recovered. The tree shows that P. ginseng is sister to P. quiquefolius with a high support value (BS = 100%), which is consistent with analysis based on expressed sequence tags (Choi et al., 2013), but differs from analyses of nuclear ITS sequences (Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Choi and Wen, 2000) and plastid intergenic spacers (Shi et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2017). The sister relationship between P. ginseng and P. quiquefolius was also supported by similar morphological traits (carrot-like main roots), habitats (temperate forests at high latitudes in East Asia and North America), and chromosome number (tetraploid, 2n = 48) (Yi et al., 2004; Choi et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2015).

|

| Fig. 4 Visualized alignment of the eight Panax plastomes. The mVISTA-based identity plots show the sequence identity among the eight Panax plastome, for which P. ginseng serves as the reference. Gray arrows indicate the position and direction of each gene. Genome regions are color-coded as protein coding, rRNA, tRNA, or conserved non-coding regions. Black lines define the regions of sequence identity shared with P. ginseng (using a 50%-identity cutoff criterion). |

P. notoginseng is a commonly cultivated medicinal herb in southwest China (Yang et al., 1988). However, its relationship to other Panax species has been disputed (e.g., Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Choi and Wen, 2000; Shi et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2017). Our results indicate that P. notoginseng, P. japonicus, and P. vietnamensis form a highly supported clade (BS = 100%), which is sister to the clade comprising of P. ginseng and P. quiquefolius; P. trifolius was found to be the earliest diverged clade of Panax, which is identical with previous analyses (Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Lee and Wen, 2004; Shi et al., 2015; Zuo et al., 2017). In previous studies, P. stipuleanatus has repeatedly shown a sister relationship with P. pseudoginseng (see Wen and Zimmer, 1996; Wen, 1999; Lee and Wen, 2004; Zuo et al., 2011, 2015, 2017); however, our phylogenomic analysis resolved P. stipuleanatus and the P. bipinnatifidus species complex as a clade (BS = 100%). Because we did not obtain a sample from P. pseudoginseng in the present study, future studies are required to resolve the position of this species.

The impact of polyploidization on plant speciation during the evolution of Panax is a particularly interesting issue. This genus contains three tetraploid species (2n = 46), P. ginseng, P. japonicus, and P. quiquefolius; furthermore, the P. bipinnatifidus species complex possesses both tetraploid and diploid species/populations (Yi et al., 2004). Our tree topologies clearly indicate that these tetraploid species were scattered in three well-supported clades, suggesting that whole genome duplication events may have occurred independently during the evolutionary history of Panax. This interpretation is supported by the study of Shi et al. (2015).

4.3. Utility of the Panax plastomesTwo plastid protein coding genes, rbcL and matK, and the psbA-trnH intergenic spacer, have been recommended as universal plastid DNA barcodes for land plants (Kress et al., 2005; Hollingsworth et al., 2011). Zuo et al. (2011) then proposed that psbA-trnH and ITS were sufficient for identifying species of Panax. However, we found that variation in rbcL and psbA-trnH was rela-tively low among the eight Panax species (at less than 1%) (Supplementary Tables S3-4). Hence, the universal plastid DNA barcodes rbcL and psbA-trnH may have limited power to identify Panax species. Thus, novel DNA barcodes for this genus are urgently needed.

Based on the sequence variations, we found nine protein-coding regions (ccsA, matK, ndhF, petL, psaI, rpl22, rpoA, rps3, and ycf1) and 10 non-coding regions (atpA-atpF, ccsA-ndhD, infA-rps8, ndhI-ndhA, psbK-psbI, rpl14-rpl16, rpl2-trnH-GUG, rpl22-rps19, rps19-rpl2, and trnY-GUA-trnE-UUC) harboring a high proportion of SNPs. We propose that these plastid DNA regions are potentially useful for identifying Panax species. Among them, matK and ycf1 have been proposed elsewhere as promising DNA barcodes (Hollingsworth et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2015), and rpl14-rpl16 have been widely used for phylogenetic studies (Shaw et al., 2014). In future studies, we will investigate whether or not these plastid DNA sequences can serve as reliable and effective DNA barcodes for rapid species identification of plants in the genus Panax.

Notably, in this study species with more than one plastome available were recovered as well-supported monophyletic groups, and different individuals of the same species generated notable genetic differentiation (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the plastome would be a reliable and accurate barcode for improving the resolution of species identification in the genus Panax. Further studies based on sampling at the population scale are needed to evaluate the efficiency of the plastome as an organelle-scale barcode.

5. ConclusionThe plastome of P. stipuleanatus, an endangered and medicinally important plant, was sequenced and assembled. The genome is 156, 069 bp in length and has a typical quadripartite structure. Comparative analysis showed that the plastomes of Panax are relatively conserved. We investigated the substitution rate of protein-coding regions, which suggest that the plastomes of Panax may have undergone strong purifying selection. We generated a well-supported phylogeny for Panax, in which P. stipuleanatus is sister to the P. bipinnatifidus species complex. Moreover, molecular markers with high sequence divergence were identified, which may be useful for phylogenetic analysis and species identification. Overall, the plastome of P. stipuleanatus will provide valuable genetic information for identifying species, phylogenetic research, as well as resource conservation.

AcknowledgementsThis research was financially supported by the Major Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31590823) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31070297). We are grateful to Jiahui Chen at the Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for his help with the data analyses.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2018.11.001.

Barrett C.F., Davis J.I., Leebens-Mack J., et al., 2013. Plastid genomes and deep relationships among the commelinids monocot angiosperms. Cladistics, 29, 65-87.

DOI:10.1111/cla.2013.29.issue-1 |

||

Choi H.I., Kim N.H., Lee J., et al., 2013. Evolutionary relationship of Panax ginseng and P. quinquefolius inferred from sequencing and comparative analysis of expressed sequence tags. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol, 60, 1377-1387.

DOI:10.1007/s10722-012-9926-3 |

||

Choi H.I., Waminal N.E., Park H.M., et al., 2014. Major repeat components covering one-third of the ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) genome and evidence for allotetraploidy. Plant J, 77, 906-916.

DOI:10.1111/tpj.2014.77.issue-6 |

||

Choi H.K., Wen J., 2000. A phylogenetic analysis of Panax (Araliaceae):integrating cp DNA restriction site and nuclear rDNA ITS sequence data. Plant Syst. Evol, 224, 109-120.

DOI:10.1007/BF00985269 |

||

Chumley T.W., Palmer J.D., Mower J.P., et al., 2006. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium × hortorum:organizationand evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol, 23, 2175-2190.

|

||

Cosner M.E., Jasen P.K., Palmer J.D., et al., 1997. The highly rearranged chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum (Campanuceae):insertions/deletions, and several repeat families. Curr. Genet, 31, 419-429.

DOI:10.1007/s002940050225 |

||

Dong W.P., Xu C., Li C.H., et al., 2015. Ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci. Rep, 5, 8348.

DOI:10.1038/srep08348 |

||

Downie S.R., Jansen R.K., 2015. A comparative analysis of whole plastid genomes from the Apiales:expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat, mitochondrial to plastid transfer of DNA, and identification of highly divergent noncoding regions. Syst. Bot, 40, 336-351.

DOI:10.1600/036364415X686620 |

||

Doyle J.J., Doyle J.L., 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull, 19, 11-15.

|

||

Frazer K.A., Pachter L., Poliakov A., et al., 2004. VISTA:computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res, 32, W273-W279.

|

||

Han Z., Li W., Liu Y., et al., 2016. The complete chloroplast genome of North American ginseng, Panax quinquefolius. Mitochondr. DNA, 27, 3496.

DOI:10.3109/19401736.2015.1066365 |

||

Hollingsworth P.M., Graham S.W., Little D.P., 2011. Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS One, 6, e19254.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019254 |

||

Huang H., Shi C., Liu Y., et al., 2014. Thirteen Camellia chloroplast genome sequences determined by high-throughput sequencing:genome structure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Evol. Biol, 14, 151.

DOI:10.1186/1471-2148-14-151 |

||

Huang Y., Li X., Yang Z., et al., 2016. Analysis of complete chloroplast genome sequences improves phylogenetic resolution in Paris (Melanthiaceae). Front. Plant Sci, 7, 1797.

|

||

Jansen R.K., Cai Z., Raubeson L.A., et al., 2007. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 104, 19369-19374.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0709121104 |

||

Katoh K., Misawa K., Kuma K.I., et al., 2002. MAFFT:a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res, 30, 3059-3066.

DOI:10.1093/nar/gkf436 |

||

Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., et al., 2012. Geneious Basic:an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics, 28, 1647-1649.

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 |

||

Kim K.J., Lee H.L., 2004. Complete chloroplast genome sequences from Korean ginseng (Panax schinseng Nees) and comparative analysis of sequence evolution among 17 vascular plants. DNA Res, 11, 247-261.

DOI:10.1093/dnares/11.4.247 |

||

Kress W.J., Wurdack K.J., Zimmer E.A., et al., 2005. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 102, 8369-8374.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0503123102 |

||

Lanfear R., Calcott B., Ho S.Y.W., et al., 2012. PartitionFinder:combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol, 29, 1695-1701.

DOI:10.1093/molbev/mss020 |

||

Langmead B., Salzberg S.L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods, 9, 357-359.

|

||

Lee C.H., Wen J., 2004. Phylogeny of Panax using chloroplast trnC-trnD intergenic region and utility of trnC-trnD in interspecific studies of plants. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol, 31, 894-903.

|

||

Li R., Ma P.F., Wen J., et al., 2013. Complete sequencing of five Araliaceae chloroplast genomes and the phylogenetic implications. PLoS One, 8, e78568.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0078568 |

||

Librado P., Rozas J., 2009. DnaSP v5:a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics, 25, 1451-1452.

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187 |

||

Liu L.X., Li R., Worth J., et al., 2017. The complete chloroplast genome of Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra, Myricaceae):implications for understanding the evolution of Fagales. Front. Plant Sci, 8, 968.

DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.00968 |

||

Lohse M., Drechsel O., Bock R., 2007. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW):a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet, 52, 267-274.

DOI:10.1007/s00294-007-0161-y |

||

Millen R.S., Olmstead R.G., Adams K.L., et al., 2001. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. Plant Cell, 13, 645-658.

DOI:10.1105/tpc.13.3.645 |

||

Moore M.J., Bell C.D., Soltis P.S., et al., 2007. Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 104, 19363-19368.

|

||

Moore M.J., Soltis P.S., Bell C.D., et al., 2010. Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, 107, 4623-4628.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0907801107 |

||

Nguyen B., Kim K., Kim Y.C., et al., 2017. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Panax vietnamensis Ha et Grushv (Araliaceae). Mitochondr. DNA, 28, 85-86.

DOI:10.3109/19401736.2015.1110810 |

||

Nock C.J., Waters D.L., Edwards M.A., et al., 2011. Chloroplast genome sequences from total DNA for plant identification. Plant Biotechnol. J, 9, 328-333.

DOI:10.1111/pbi.2011.9.issue-3 |

||

Nurk, S., Bankevich, A., Antipov, D., et al., 2013. Assembling genomes and mini-meta genomes from highly chimeric reads. In: Deng, M., Jiang, R., Sun, F., et al. (Eds.), Research in Computational Molecular Biology, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 158-170. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-37195-0_13

|

||

Parks M., Cronn R., Liston A., 2009. Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol, 7, 1.

DOI:10.1186/1741-7007-7-1 |

||

Patel R.K., Jain M., 2012. NGS QC Toolkit:a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One, 7, e30619.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 |

||

Philippe H., Brinkmann H., Lavrov D.V., et al., 2011. Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions:why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol, 9, e1000602.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602 |

||

Plunlett G.M., Downie S.R., 2000. Expansion and contraction of the chloroplast inverted repeat in Apiaceae subfamily Apioideae. Syst. Bot, 25, 648-667.

DOI:10.2307/2666726 |

||

Raubeson, L.A., Jansen, R.K., 2005. Chloroplast genomes of plants. In: Henry, R.J.(Ed.), Plant Diversity and Evolution: Genotypic and Phenotypic Variation in Higher Plants. CABI, Cambridge, pp. 45-68. https://www.cabdirect.org/?target=%2fcabdirect%2fabstract%2f20083015358

|

||

Rokas A., Carroll S.B., 2005. More genes or more taxa? The relative contribution of gene number and taxon number to phylogenetic accuracy. Mol. Biol. Evol, 22, 1337-1344.

DOI:10.1093/molbev/msi121 |

||

Ruhsam M., Rai H.S., Mathews S., et al., 2015. Does complete plastid genome sequencing improve species discrimination and phylogenetic resolution in Araucaria? Mol. Ecol. Resour, 15, 1067-1078.

DOI:10.1111/1755-0998.12375 |

||

Schattner P., Brooks A.N., Lowe T.M., 2005. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res, 33, W686-W689.

DOI:10.1093/nar/gki366 |

||

Shaw J., Shafer H.L., Leonard O.R., et al., 2014. Chloroplast DNA sequence utility for the lowest phylogenetic and phylogeographic inferences in angiosperms:the tortoise and the hare Ⅳ. Am. J. Bot, 101, 1987-2004.

DOI:10.3732/ajb.1400398 |

||

Shi F.X., Li M.R., Li Y.L., et al., 2015. The impacts of polyploidy, geographic and ecological isolations on the diversification of Panax (Araliaceae). BMC Plant Biol, 15, 297.

DOI:10.1186/s12870-015-0669-0 |

||

Stamatakis A., 2006. RAxML-Ⅵ-HPC:maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analysis with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics, 22, 2688-2690.

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 |

||

Stull G.W., de Stefano R.D., Soltis D.E., et al., 2015. Resolving basal lamiid phylogeny and the circumscription of Icacinaceae with a plastome-scale data set. Am. J. Bot, 102, 1794-1813.

DOI:10.3732/ajb.1500298 |

||

Wen J., 1999. Evolution of eastern Asian and eastern North American disjunct pattern inflowering plants. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst, 30, 421-455.

DOI:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.421 |

||

Wen J., Zimmer E.A., 1996. Phylogeny and biogeography of Panax L. (the ginseng genus):inferences from ITS sequences of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol, 6, 167-177.

DOI:10.1006/mpev.1996.0069 |

||

Wick R.R., Schultz M.B., Zobel J., et al., 2015. Bandage:interactive visualisation of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 31, 3350-3352.

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv383 |

||

Wicke S., Schneeweiss G.M., Depamphilis C.W., et al., 2011. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants:gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol, 76, 273-297.

DOI:10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4 |

||

Wiens J.J., 2003. Missing data, incomplete taxa, and phylogenetic accuracy. Syst. Biol, 52, 528-538.

DOI:10.1080/10635150390218330 |

||

Wyman S.K., Jansen R.K., Boore J.L., 2004. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics, 20, 3252-3255.

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352 |

||

Xiang, Q.B., Lowry, P.P., 2007. Panax. In: Wu, Z.Y., Raren, P.H. (Eds.), Flora of China, vol. 13. Science Press, Beijing, pp. 489-491.

|

||

Yang Z., Ji Y., 2017. Comparative and phylogenetic analyses of the complete chloroplast genomes of three Arcto-Tertiary relicts:Camptotheca acuminata, Davidia involucrata, and Nyssa sinensis. Front. Plant Sci, 8, 1536.

DOI:10.3389/fpls.2017.01536 |

||

Yang C.R., Zhou J., Tanaka O., 1988. Chemotaxonomy of Panax and its application of medical resources. Acta Bot. Yun(Suppl. Ⅰ), 47-62.

|

||

Yang J.B., Li D.Z., Li H.T., 2014. Highly effective sequencing whole chloroplast genomes of angiosperms by nine novel universal primer pairs. Mol. Ecol. Resour, 14, 1024-1031.

|

||

Yang J.B., Tang M., Li H.T., et al., 2013. Complete chloroplast genome of the genus Cymbidium:lights into the species identification, phylogenetic implications and population genetic analyses. BMC Evol. Biol, 13, 1.

DOI:10.1186/1471-2148-13-1 |

||

Yang Z., Nielsen R., 2000. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol, 17, 32-43.

DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236 |

||

Yao X., Tan Y.H., Liu Y.Y., et al., 2016. Chloroplast genome structure in Ilex (Aquifoliaceae). Sci. Rep, 6, 28559.

DOI:10.1038/srep28559 |

||

Yi T., Lowry Ⅱ P.P., Plunkett G.M., et al., 2004. Chromosomal evolution in Araliaceae and close relatives. Taxon, 53, 987-1005.

DOI:10.2307/4135565 |

||

Zhang D., Li W., Gao C., et al., 2016. The complete plastid genome sequence of Panax notoginseng, a famous traditional Chinese medicinal plant of the family Araliaceae. Mitochondr. DNA, 27, 3438.

DOI:10.3109/19401736.2015.1063131 |

||

Zhao Y., Yin J., Guo H., et al., 2015. The complete chloroplast genome provides insight into the evolution and polymorphism of Panax ginseng. Front. Plant Sci, 5, 696.

|

||

Zhou T., Wang J., Jia Y., et al., 2018. Comparative chloroplast genome analyses of species in gentiana section Cruciata (Gentianaceae) and the development of authentication markers. Int. J. Mol. Sci, 19, 1962.

DOI:10.3390/ijms19071962 |

||

Zhu S., Fushimi H., Cai S., et al., 2003. Phylogenetic relationship in the genus Panax:inferred from chloroplast trnK gene and nuclear 18S rRNA gene sequences. Planta Med, 69, 647-653.

DOI:10.1055/s-2003-41117 |

||

Zuo Y., Chen Z., Kondo K., et al., 2011. DNA barcoding of Panax species. Planta Med, 77, 182-187.

DOI:10.1055/s-0030-1250166 |

||

Zuo Y.J., Wen J., Ma J.S., et al., 2015. Evolutionary radiation of the Panax bipinnatifidus species complex (Araliaceae) in the Sino-Himalayan region of eastern Asia as inferred from AFLP analysis. J. Syst. Evol, 53, 210-220.

DOI:10.1111/jse.v53.3 |

||

Zuo Y.J., Wen J., Zhou S.L., 2017. Intercontinental and intracontinental biogeography of the eastern Asianeeastern North American disjunct Panax (the ginseng genus, Araliaceae), emphasizing its diversification processes in eastern Asia. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol, 117, 60-74.

DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.06.016 |