b. Key Laboratory of Ethnomedicine (Minzu University of China), Ministry of Education, Beijing, 100081, China;

c. Institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, 15170, Mongolia;

d. Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Ulaanbaatar, 210351, Mongolia;

e. College of Geographical Science, Inner Mongolia Normal University, Hohhot, 010022, China;

f. Department of Geography, School of Arts and Sciences, National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, 14201, Mongolia;

g. School of Pharmacy, Minzu University of China, Beijing, 100081, China

Folk taxonomy and nomenclature are common in the world (Loko et al., 2018; Tokuoka et al., 2019). The local people use their own knowledge to name plants, animals and microorganisms (Phaka et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). The traditional knowledge of classification, identification and nomenclature has shown significant values in nature conservation and biodiversity uses (Turpin and Si, 2017; Ulicsni et al., 2016). Traditional knowledge (TK) associated with biodiversity covers the folk nomenclature systems, uses of bioresources available, and management of ecosystems by the local people of a given area (Khasbagan et al., 2000).

Folk nomenclature of plant species are the roots of traditional botanical knowledge (Khasbagan and Soyolt, 2008; Li et al., 2013). Thus it will be impossible to hand TK down to future generations. Collection and analysis of plant folk names of the Mongolians are extremely important because of the rapid socio-economic changes and desertification of grasslands in the country. Unfortunately few investigations had been conducted to document the folk names of plants in Mongolia. On the other hand, ethnobotanical investigation in Inner Mongolia have been carried out since 1980s, including useful plants of herders (Village and Khasbagan, 2017), and folk nomenclature (Soyolt et al., 2013).

The genus Cistanche Hoffmg. et Link is a group of perennial parasitic herbaceous plants in the family Orobanchaceae. About 20 species had been described in the genus, with distribution in Asia and Europe (Zhang and Tzvelev, 1998). Most of their host plants are sand-binding plants such as some species in Kalidium Miq., Haloxylon Bunge and Tamarix L. (Li et al., 2019), and Ammopiptanthus mongolicus (Maximowicz) Cheng, Caragana tibetica Komarov, Potaninia mongolica Maximowicz, Reaumuria soongarica (Pallas) Maximowicz, Salsola passerina Bunge, Tetraena mongolica Maximowicz, and Zygophyllum xanthoxylon (Bunge) Maximowicz. Other members in Amaranthaceae (mostly from the former Chenopodiaceae) may also be their host plants (Zhang and Tzvelev, 1998).

"Conservation Flora MNR" recorded three species of Cistanche or Argamjin tsetseg in Mongolia. They are Cistanche feddenia K.S. Hao, C. salsa (C.A. Meyer) G. Beck, and C. tubulosa (Schenk) R. Wright. In the Key to Vascular Plants of Mongolia, two species of Cistanche were included, i.e. C. feddenia and C. salsa. A Russian scientist Gubanov (1996) had recorded four species of Cistanche in Conspectus of Flora in Outer Mongolia. They are: 1) Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma, 2) Cistanche lanzhouensis Z.Y. Zang, 3) C. ningxiaensis D.Z. Ma et J.A. Duan, and 4) C. salsa. The taxa, C. feddenia was divided into two species (Grubov, 1982). Among all Cistanche species, C. deserticola is the most valuable and widely used for medicinal purposes in different countries.

Cistanche deserticola is mainly distributed in China (Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Gansu, and Qinghai), Iran, India and Mongolia (Wang et al., 2012). C. deserticola has its own viable green leaf and root system, turning roots and leaves into parasites. The breeding organ stem has gained considerable resemnlance, but research has shown selectivity. It is also of the highest interest in breeding.

Scientists had studied Cistanche species since 1980s (Kobayashi and Komotsu, 1983). Hundreds of publications had been issued in recent 20 years (Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). The chemical analysis demonstrated that phenylethanoid glycosides, iridoids, betaine, Krebs cycle intermediates, lignans, alditols, oligosaccharides and polysaccharides are the main compounds in Cistanche plants (Lun et al., 2005; Li et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Pharmacological research showed that the extracts from Cistanche plants possess a wide spectrum of activities, such as curing kidney deficiency and senile constipation, advancing the ability to study and memorize, enhancing immunity, anti-aging and antifatigue. Phytochemical studies on this genus have revealed the chemical constituent of Cistanche plants (Jiang and Tu, 2009; Li et al., 2016). The wild C. deserticola has been on the edge of extinction due to over-harvesting for medicinal uses, and it has been listed as one of the Grade-II plants needing protection in China.

However, little records of traditional knowledge associated with Cistanche and its plant community had been reported in Mongolia. The aim of this paper is to document the folk names of species in plant community where C. deserticola occurs in Mongolia (thereafter Cistanche-associated community, or shortly Cistanche community) based on ethnobotanical investigations. The folk nomenclature of C. deserticola in Mongolian Gobi will be presented in the paper. Some issues related to plant conservation in Cistanche community will be argued.

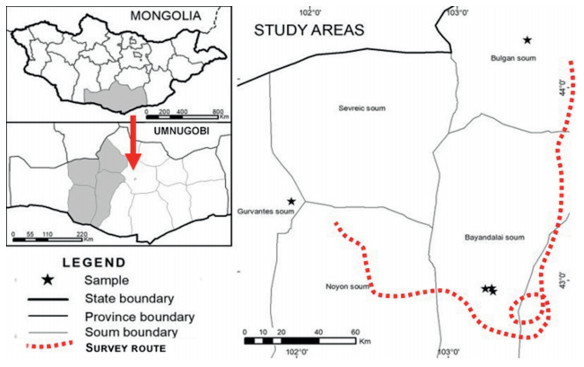

2. Material and methods 2.1. The study areaThe study area is in Umnugobi of Southern Gobi Desert area. Umnugobi is the biggest province in Mongolia, with a total area of 165, 500 km2 and a population of about 66.7 thousand (NSO, 2020). The climate here is extreme in Umnugobi Province. Its temperatures reach up to +40 ℃ in summer, and -30 ℃ in winter. Precipitation averages less than 100 mm per year, while in some areas it rains only once every two or three years.

The study was carried out in five sites: Zuun Bukht, Zuramtai Mountain, Naran Bag, Jaran Sand, and Tevsh Khairkhan, located in Umnugobi Province of Southern Gobi Desert area (between 24°12'-26°86' N and 98°13-102°42' E) (Fig. 1).

|

| Fig. 1 Study areas in Umnugobi Province shown sample sites. |

All literatures related to Umnugobi Province were collected. The local names, frequency of uses, and other values of Cistanche were gathered from the literatures. Fieldworks were conducted from April 25 to August 12, 2019. Ethnobotanical data were collected from the field investigations in five selected sites (Table 1). Fieldworks were carried out in five villages, and 58 local herders as key informants were interviewed. The informants* age varied from 18 to 75 years old (comprising 25 males and 33 females). Key informants own rich traditional knowledge about the Cistanche including habitat of old Cistanche in saxaul forest area. They guided us to visit the saxaul forest area as well. Particular attention was paid to collect information about folk names of Cistanche (Table 1) and other species in the plant community. While noting the information, all relevant taxonomic characteristics were documented. The identification was done by consulting with an expert: botanist Battseren Munkhjargal, Department of Botany, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, and through several literature sources. The determined species were further compared with the "Key to the Vascular Plants of Mongolia" for justification of correct scientific names and author citations (Urgamal et al., 2019). All voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium, Mongolian Academy of Sciences.

| No. | City | Site | Longitude | Latitude |

| 1 | Bayandalai Soum | Zuun Bukht, Zuramtai Mountain, saxaul forest | 103°17'15.7" | 42°56'13" |

| 2 | Bayandalai Soum | Zuun Bukht, Zuramtai Mountain, Ephedra steppe | 103°16'39.9" | 42°57'15" |

| 3 | Bayandalai Soum | Naran Bag | 103°14'12.5" | 42°57'03" |

| 4 | Gurvantes Soum | North part of Jaran Sand, saxaul forest | 101°55'36.6" | 43°22'37" |

| 5 | Bulgan Soum | Tevsh Mountain, saxaul forest | 103°28'57.5" | 44°14'50" |

The methods of semi-structured interviews were used in field surveys. Ethnobotanical interviews were organized in two ways: local plant specimens were collected beforehand and then interviews were organized; and local herders were invited to the field and were interviewed. Mongolian was used as the working language, and findings were recorded in Mongolian. Folk names of plants were confirmed through collection and identification of voucher specimens.

3. Results 3.1. The Cistanche-associated communityBased on the identification results of specimens collected from the Cistanche-associated community, the folk names of all plants corresponded with 96 species which belong to 26 families and 71 genera. Most species were confirmed as recorded by Ulziykhutag (1985) and Urgamal (2018). Some literatures did not report extensive research on species components of Mongolian saxaul forest, such as Gal (1972) who had given an overview of their work (Gal, 1972). The saxaul forest range is considered to be an independent region of the Asian desert. Its components are mostly from Asteraceae, Amaranthaceae, Zygophyllaceae, Poaceae, and other xerophytes, halophytes, gypsites and psamophytes.

The most dominant species in the Cistanche-associated community are Peganum nigellastrum, Salsola collina, Aristida heymannii, and Agriophyllum pungens, and co-dominants are Salsola passerine, Anabasis salsa, Calligonum mongolicum, Nitraria sibirica, and Stipa gobica in the saxaul forest (Fig. 2) (Table 2). Some photos of additional plants in the Cistanche-associated community may be available in the supplementary material (Fig. S1).

|

| Fig. 2 Cistanche deserticola-associated communities. |

| Life form | Habit | Species |

| Eucerophytes, halophytes, gypsites | Shrub | Calligonum mongolicum, Atraphaxis pungens, Zygophyllum xanthoxylon, Tamarix ramosissima, Nitraria sibirica, Nitraria roborowskii. |

| Subshrubs | Anabasis aphylla, Anabasis eriopodia, Eurotia ceratoides, Eurotia ewersmanniana, Artemisia xerophytica, Convolvulus gortschokovii, Ephedra przewalskii, Salsola ikonnikovii, Salsola passerine, Sympegma regelii, Kallidium cuspidatum, Kallidium fliatum, Kallidium gracile, Caragana microphylla. | |

| Mesoxero-galophyte | Biennial and annual herbaceous plants | Chesneya mongolica, Artemisia gobica, Lasiagrostis splendens, Chloris virgata, Pappopnorum boreale, Aristida adscensionis, Setaria viridis, Cleistogens mutica, Eragrostost, Elymus ginganteus, Asparagus gobicum, Rheum nanum, Chenopodium acuminatum, Echinopsilon divaricatum, Corispermum mongolicum, Agriophyllum gobicum, Sueda corniculata, Salsola ikonnikovii, Halogeton glomeratus, Halogeton arachnoideus |

The scientific names, Mongolian names and folk names were presented, alphabetically listed by family, genus, and species name spellings. The confirmation of some species was mainly based on publications of Grubov (2001), Gubanov (1996), Urgamal et al. (2017).

3.2. Folk names of plants in Cistanche-associated communityThe vascular plants of Cistanche-associated community were listed in Table 3 according to the most recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG IV, 2016) and other research results. We compared Mongolian names with folk names about all species in Cistanche community, and showed different naming systems by morphology, original places and traditional uses of the recorded plants (Table 3).

| Family | Scientific name | Mongolian name | Folk name |

| Amaranthaceae | Agriophyllum pungens (Vahl.) Link | Shivuurt tsulihir | Derveen tsulihir |

| Amaranthaceae | Anabasis brevifolia C. A. Mey. | Ahar navchit bagluur | Bagluur |

| Amaranthaceae | Atriplex sibirica L. | Sibiri shornoi | Gagadai, Luuli |

| Amaranthaceae | Bassia dasyphylla (Fisch. et Mey.) | Usleg manan-hamhag | Ust hamhag |

| Amaranthaceae | Chenopodium acuminatum Willd. | Shorgor luuli | Shornoi luuli |

| Amaranthaceae | Corispermum mongolicum Iljin | Mongol hamhuul | Horon hamhag |

| Amaranthaceae | Eurota ceratoides (L.) C. A. Mey. | Orog teseg | Tsomtsogt teseg |

| Amaranthaceae | Haloxylon ammodendron (C.A. Mey.) Bunge | Zag | Tsagaan zag |

| Amaranthaceae | Halogeton glomeratus (Bieb.) | Bag hush-hamhag | Hush-hamhag |

| Amaranthaceae | Kalidium foliatum (Pall.) Moq. | Navchirhagshar budargana | Undur shar, Shar budargana |

| Amaranthaceae | K. gracile Fenzl | Goolig badargana | Shar mod |

| Amaranthaceae | Salsola passerina Bunge | Bor budargana | Toson budargana |

| Amaranthaceae | S. pestifera Hels. | Urgust budargana | Urgust hamhuul |

| Amaranthaceae | Sympegma Regelii Bunge | Regeliin shar mod | Shar mod |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium mongolicum Regel | Humul | Humuul |

| Amaryllidaceae | A. anisopodium Ldb. | Sarvuun songino | Shuvuun hul |

| Amaryllidaceae | A. polyrrhizum Turcz. ex Regel | Taana | Taana |

| Apiaceae | Ferula bungeania Kitag. | Bungiin havrag | Havrag |

| Asclepiadaceae | Vincetoxicum sibiricum (L.) Decne | Sibiri erundgunu | Temeen huh |

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus gobicus Ivanova ex Grub. | Goviin hereen nud | Hereen nud |

| Asteraceae | Ajania fruticulosa (Ldb.) Poljak. | Suugun borolz | Bortaari |

| Asteraceae | Artemisia pectinata Pall. | Shulhii sharilj | Uher shulhii |

| Asteraceae | A. intricata Franch. | Orooldoo sharilj | Bor tulug |

| Asteraceae | A. anethifolia Web. ex Stechm. | Bojmog sharilj | Bojmog sharilj |

| Asteraceae | A. scoparia Waldst. et Kit. | Yamaan sharilj | Yamaan sharilj |

| Asteraceae | A. xerophytica Krasch. | Huuraisag sharilj | Bor shavag |

| Asteraceae | A. annua L. | Morin sharilj | Morin sharilj |

| Asteraceae | A. xanthochroa Krasch. | Shar sharilj | Shar shavag |

| Asteraceae | Asterothamnus centrali- asiaticus Novopokr. | Tuv aziin lavai | Bor lavai |

| Asteraceae | Brachanthemum gobicum Krasch. | Goviin tost | Umhii tulee |

| Asteraceae | Cancrinia discoidea (Ldb.) Poljak. | Zeerentseg altan tovch | Altan tovch |

| Asteraceae | Echinops gmelinii Turcz. | Gmelinii taijiin jins | Aduun uruul |

| Asteraceae | Heteropappus altaicus (Willd.) Novopokr | Altain sogsoot | Altain sogsoolj |

| Asteraceae | Lactuca tatarica (L.) C.A. Mey. | Tataar ziraa | Ziraa |

| Asteraceae | Saussurea salsa (Pall.) Spreng. | Martsnii banzdoo | Banzdoo |

| Asteraceae | S. amara DC. | Gashuun banzdoo | Gazriin huh |

| Asteraceae | Scorzonera divaricata Turcz. | Derevger havishana | Suut uvs |

| Asteraceae | S. capito Maxim. | Danhar havishana | Hurgan chih |

| Asteraceae | Taraxacum leucanthum (Ldb.) Ldb. | Tsagan tsetsegt bagvahai | Bagvaahai |

| Bignoniaceae | Incarvillea potaninia Batal. | Potaninii ulaan tulam | Tsagaan halgai |

| Boraginaceae | Arnebia guttata Bunge | Tolbot bereemeg | Bor elgene |

| Boraginaceae | Lappula intermedia (Ldb.) M. Pop | Zavsriin notsorgono | Zavsriin notsgono |

| Brassicaceae | Dontostemon senilis Maxim. | Utluun bagdai | Zurgaadai bagdai |

| Brassicaceae | Isatis costata C. A. Mey. | Gurvent huhurgunu | Havirgat huhurgunu |

| Brassicaceae | Ptilotrichum canescens (DC) C. A. Mey. | Buuralduu yangits | Tsagaan demeg |

| Convolvulaceae | Convolvulus ammanii Desr. | Ammanii sedergene | Sedergene |

| Convolvulaceae | C. gortschakovii Schrenk | Gorchakoviin sedergene | Shar bereemeg, |

| Cynomoriaceae | Cynomorium songaricum Rupr. | Zuungariin goyo | Ulaan goyo |

| Ephedraceae | Ephedra sinica Stapf | Nangiad zeergene | Zeergene |

| Ephedraceae | E. monosperma S. G. Gmel. ex C. A. Mey. | Yamaan zeergene | Yamaan zeergene |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia humifusa Schlecht | Nalchigar suut uvs | Suut uvs |

| Fabaceae | Astragalus variabilis Bunge ex Maxim. | Huvisangi hunchir | Horon hunchir |

| Fabaceae | A. junatovii Sancz. | Yunatoviin hunchir | Yunatoviin hunchir |

| Fabaceae | A. grubovii Sancz. | Gruboviin hunchir | Gruboviin hunchir |

| Fabaceae | A. monophyllus Bge. | Gants navchit hunchir | Gantsnavchintsart hunchir |

| Fabaceae | A. laguroides Pall. | Tuulain hunchir | Bujin hunchir |

| Fabaceae | Chesneya mongolica Maxim. | Mongol buurtsgana | Buurtsgana |

| Fabaceae | Caragana leucophloea Pojark. | Altan hargana | Ulaan hargana Altargana |

| Fabaceae | Oxytropis aciphylla Ledeb. | Urgust ortuuz | Ortuuz |

| Geraniaceae | Erodium stephanianum Willd. | Stepanii zaan tavag | Zaan tavag |

| Geraniaceae | E. tibetanum Edgew. | Tuvd zaan tavag | Hereen hoshuu |

| Iridaceae | Iris tenuifolia Pall. | Nariin tsahildag | Tsulbuur ubs |

| Iridaceae | I. lactea Pall. | Tsagaalin tsahildag | Hos hairst tsahildag |

| Lamiaceae | Lagochilus ilicifolius Bunge | Yamaan angalzuur | Tsarsnavchit angalzuur |

| Lamiaceae | Panzeria lanata (L.) Bun ge | Ushii nohoin hel | Temeen angalzuur |

| Orobanchaceae | Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma | Argamjin tsetseg | Tsagaan goyo |

| Plantaginaceae | Plantago minuta Pall. | Baga tavan salaa | Ulaan tulam |

| Plumbaginaceae | Limonium aureum (L.) Hill et Ktze | Altan bereemeg | Shar bermeg |

| Plumbaginaceae | L. tenellum (Turcz.) Ktze. | Tuyahan bereemeg | Tuyahan bermeg |

| Poaceae | Aristida heymannii Regel | Geimaniin buudii | Nohoin shivee |

| Poaceae | Cleistogenes soongorica (Roshev.) Ohwi | Zuungariin hazaar uvs | Sorgui hazaar uvs |

| Poaceae | Enneapogon desvauxii P.Beauv. | Umardiin ogotniin suul | Hurgalj, Budnuur |

| Poaceae | Eragrostis minor Host. | Baga hurgalj | Budneen ur |

| Poaceae | Leymus paboanus (Claus) Pilg. | Paboani Tsagaan suli | Suli |

| Poaceae | Ptilagrostis pelliot (Danguy) Grub. | Pellitiin yet uvs | Yet uvs |

| Poaceae | Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. | Nogoon honog budaa | Hermen suul |

| Poaceae | Stipa gobica Roshev. | Goviin hyalgana | Mongol uvs |

| Poaceae | S. glareosa var. pubescens Gub. | Sairiin hyalgana | Mongol hyalgana |

| Polygonaceae | Atraphaxis pungens (Biab.) | Urgust emgen shilbe | Emgen shilbe |

| Polygonaceae | A. frutescens (L.) K. Koch. | Suugun emgen shilbe | Tsagaan mod |

| Polygonaceae | Calligonum mongolicum Turcz. | Mongol azar | Toson torlog |

| Polygonaceae | Rheum nanum Siev. | Namhan gishuune | Bajuuna |

| Rosaceae | Amygdalus pedunculata Pall. | Bariult builes | Builees |

| Rosaceae | Potaninia mongolica Maxim. | Hulan hoirgo | Mongol hoirog |

| Rosaceae | Sibbaldianthe sericea Grub. | Torgon hereen hoshuu | Torgomsog hereen hoshuu |

| Salicaceae | Populus diversifolia Schrenk | Eldev navchit ulias | Tooroi, Turaanga |

| Tamaricaceae | Reaumuria soongarica (Pall.) Maxim. | Zuungariin budargana | Ulaan budargana |

| Tamaricaceae | Tamarix ramosissima Ledeb. | Olon tsetsegt suhai | Ulaan suhai |

| Ulmaceae | Ulmus pumila L. | Odoi hailas | Tarvagan hailas |

| Verbenaceae | Caryopteris mongolica Bge. | Mongol dogor | Yamaan ever |

| Zygophyllaceae | Nitraria sibirica Pall. | Sibiri harmag | Tovtsog harmag |

| Zygophyllaceae | Peganum nigellastrum Bge. | Harlag umhii uvs | Umhii uvs |

| Zygophyllaceae | Tribulus terrestris L. | Zelen zanguu | Nohoi zanguu |

| Zygophyllaceae | Zygophyllum xanthoxylon (Bge.) Maxim. | Shar hotir | Nohoin sheerenge |

| Zygophyllaceae | Z. rosovii Bunge | Rozoviin hotir | Botgon tavag |

| Zygophyllaceae | Z. potaninii Maxim. | Potaninii hotir | Argaliin und |

As shown in Table 3, the plants recorded from the Cistanche-associated community are mostly perennial herbaceous with 72 species, accounting for 75% of the total number of plants. Annual herbaceous plants of 24 species occupy 25%. There are 11 species of shrubs in the community, occupying 11.5%.

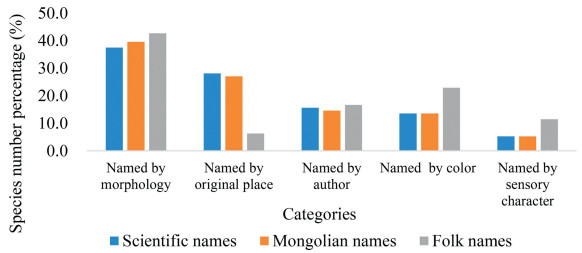

Mongolians have rich and unique traditional knowledge because of their long-term survival in the pasturelands and desert areas. The local people in South Gobi named wild plants based on their traditional knowledge (Fig. 3).

|

| Fig. 3 Meanings of plant names in the Cistanche community. |

The plant names mostly presented the information of plants. A comparison of meanings of plant names in the Cistanche community was shown in Fig. 3. The plant names in Cistanche community could be divided into five categories including morphology, original place, author name, color, and sensory character. In the scientific names of plants, the category of morphological characteristics constituted the highest proportion represented by 36 species (37.5%), while there were 15 species (15.6%) named in memory of authors and authority botanists or other people, 13 (13.5%) for color, 27 (28.1%) for original place, and 5 (5.2%) for sensory character. In Mongolian names, species named by morphological characteristics reached 38 species (39.6%), original place was 26 (27.1%), author name was 14 (14.6%), color was 13 (13.5%), and sensory character was 5 (5.2%). According to these data, the scientific and Mongolian names are not significantly different in five categories. That means the Mongolian names and scientific names are very similar by using all of categories as translated into Mongolian language.

The folk names indicated that meanings of plants were ranked by morphological characteristics (42.7%), color (22.9%), and sensory character (11.5%). The author names was 14 (14.6%), the same as that of scientific and Mongolian names. But the original place (27.1%) was quite different from other categories in folk names. In scientific nomenclature, the morphological characteristics of a plant is usually used to name the species. The original place names revealed the origins of plants, the first sites to collect specimens or their growing environment, such as Mongolia, Zuungariin gobi, Sibiri, Tataar, Soutern Gobi, borderland, dryland and marsh, and others. Some plants were named in memory of the botanists' names who firstly discovered the plants. This category is almost equal in scientific, Mongolian and folk names. For example, Amman, Bunge, Gmelin, Grubov, Potanin, Regel, Rozov, Yunatov and other botanists or authors had been used to name the plants. Scientifically the Latin names are used as classifying or identifying specific plants. The name of a plant is also given by the color of flowers, or stem, or leaves which have golden, brown, grey, green, pearl grey, yellow, white, stain or other colors. The meanings of names related to sensory characters have been identified as edible, salty, poisonous, tasteless, stinky or oily, which reflected the local people's traditional knowledge about these plants.

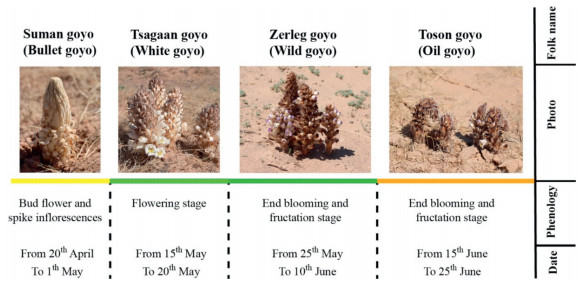

3.3. Folk nomenclature of Cistanche deserticolaSix folk names of Cistanche deserticola were recorded (Table 4). The plant grows in two forms: red and white. The white one is called "Tsoliin Argamjin tsetseg" and plays a key role in maintaining the local Gobi ecosystem.

| Scientific name | Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma |

| Mongolian name | Tsoliin Argamjin tsetseg |

| Folk names | 1) Tsagaan goyo; 2) Zerleg goyo; 3) Toson goyo; 4) Suman goyo; 5) Tatigshamo; 6) Goyohoi |

| Life form and morphology | Parasitic plant, with inflorescences up to 30 cm long (occasionally up to 50 cm), pale pink, sparse hairy, flower petals very short. Desert shrubs are good for breeding and are capable of producing up to 330 flowers per plant and producing about 2, 000, 000 seeds. Seeds survive for 10-12 years without losing germination. |

| Habitat | It grows mainly on thick sandy dunes in the Central Asian desert called Gobi. |

Tsoliin Argamjin tsetseg is the Mongolian name for Cistanche deserticola. Because it mainly grows on the roots of Haloxylon ammodendron, and the name comes from the Mongolian which means tethering animals in the desert. Another possibility is because it grows on sand dunes like a rope made of animal's hair. Under the species level of Tsoliin Argamjin tsetseg, six folk names were used. This species in South Gobi has been called "goyo" for a long history (Ligaa et al., 2006; Khurelchuluun et al., 2007). Therefore, "goyo" appeared in five names.

The only exception is Tatigshamo

Goyohoi (No. 6) is a folk name for a type of Cistanche deserticola. It refers to the C. deserticola with small size but beautiful flower. Goyohoi is very rarely occurred. Other four folk names (No. 1-4: Tsagaan goyo, Zerleg goyo, and Suman goyo) are related to the principal growth stage and development of C. deserticola. The explainations are shown in Fig. 4.

|

| Fig. 4 Principal growth stage related to folk names of Cistanche deserticola. |

Suman goyo (Bullet goyo): It is probably because it protrudes from the ground, like a shotgun's bullet. At the bud flower and spike inflorescences stage (Zhang and Tzvelev, 1998) of Cistanche deserticola, it is 50-150 (sometimes 250) cm high, with stem rounded, diameter 8 (-20) cm, opposite scales, with wide scaly apex, dense surface yellowish or pale yellow, bluish-brown after flowering it becomes colored. The lower part of the stem, which is located at the base of the stem, is coarse, with a cylindrical shape. The scales are often blunt. It resembles like shotgun's bullet form.

Tsagaan goyo (White goyo): The flowering stage starts in early or mid-May (Fig. 3), with year to year variations. During the flowering stage, some small floret buds may also form at the top of each side axis of the inflorescence and at the base of each floret group. Inflorescences with drooping flowers begin to bloom from about May 1, and full bloom occurs on May 15-20, and from then on.

Zerleg goyo (Wild goyo): In Mongolia, this type is rarely found. Some plants that do not bloom in the spring will bloom in the fall (September-October) when the moisture content is higher. But they will often fail to produce fruits.

Toson goyo (Oil goyo): Stage of end blooming and fructation of Cistanche deserticola is more useful. When the flowering phase is over and the plants are mowing, the resinous liquid is released from the plant. Apart from the fact that the people called resinous liquid as oil, it was also named after the name of the land because of the widespread distribution of the place Tost and Toson Bumba in Umnugobi Province.

We found six developmental stages of Cistanche deserticola: bud flower, inflorescence emergence, full flowering, end blooming, senescence and beginning of dormancy. The local people named four flowering stages with different names. It is useful that the growth cycle of C. deserticola was differed by folk names in southern Mongolia.

3.4. Folk usage and conservation of Cistanche deserticolaThe informants reported that the Gobi bear eats a little of Cistanche deserticola during the flowering period, and after flowering. The local people has used it to strengthen valetudinarian animals. C. deserticola has been used in traditional Mongolian medicine to heal wounds and stomach aches of children. C. deserticola has been used in combination with fluoride for headaches, jaundice, and stomach cramps due to its ability to suppress jaundice and digestion.

In traditional Mongolian medicine, the healing properties of white goyo and red goyo are considered to be similar, and they are also called "oil goyo". It has been a leading fitness medicine for many years and used in traditional medicine. In particular, C. deserticola is regarded as one of the best herbal medicines to treat some diseases such as male premature ejaculation and ejaculation, infertility in women, cold back pain, and anemia.

It is common to sink the fleshy stems of Cistanche deserticola in alcohol at about 40° in local societies. The dried C. deserticola plants are also used for medicinal purposes. Other uses had not been reported.

Cistanche deserticola has, unfortunately, become endangered due to various reasons. The major factors to threat C. deserticola are destruction of saxaul forest, overharvest because of increasing market demand, and drought resulted from global environmental change. It has been included in the Mongolian Law on Plants as a rare plant. In the 2nd edition of the "Mongolian Red Book" (1997), it was registered as a very rare and endangered plant. As the only rare and endangered parasitic plant species, it has been included in the 3rd edition of the "Mongolian Red Book" (2013) as an endangered species, and listed in the Mongolian Plant Red List and Conservation Plan (2012).

4. DiscussionResearches about folk nomenclature of Cistanche deserticola and other plants in the community were very rare in Mongolia and other countries. Mongolian botanists studied plant systematics (Ulziikhutag, 1984; Manibazar, 2000; Sanchir, 1999; Urgamal et al., 2019), especially the identification with scientific nomenclature (Banzragch and Luvsanjav, 1965). But none had studied the folk nomenclature. We documented the folk names and Mongolian names of plants in the Cistanche-associated community. In particular, folk names of C. deserticola related to plant morphology and phenology were described. The folk nomenclature for C. deserticola is very useful for people to understand this important medicinal plant, especially its different developmental stages (No. 1-4), its special form (No. 5), and its medicinal property (No. 6).

Based on our field surveys in the Gobi region, local people have a lot of traditional knowledge to recognize plant species and plant phenology by giving them different names based on morphological and ecological characteristics. Similarities exist in folk and scientific taxonomy. Some folk names for plants in our study areas are similar to those of binomial nomenclature (e.g. names for species in Artemisia).

Meanings of names with morphological characteristics showed that physical form and external structure of plants (height, inflorescence, handle, roof, pony, in the shower, or thorns). Additionally, the meanings of folk names contained morphological, color and sensory characters of plants, but only a few original places were recorded because the herders live usually in an area smaller than the plant distribution range. The meaning of name with color is dominant in folk names compared with the other two-name categories (scientific and Mongolian names). The local people mostly named plants by colors of plant parts (leaves, stems, flowers and others). To compare with scientific and Mongolian names, the folk names with sensory characters are used very often for the plants in Cistanche-associated community. As the locals do not know the scientific or even Mongolian names, they named plants by sensory characters based on their traditional uses. Therefore, they prefer to give names to plants followed sensory characteristics. There are many cases when the names of different species of plants overlap, and due to this, it is often the case that non-medicinal plants of the same name are wrongly used. For example, two names, red goyo and white goyo, are called "Goyo" under the same folk name, but the scientific names are different. That is, red goyo is for Cynomorium songaricum Rupr., while white goyo is for Cistanche deserticola.

In some cases, there are several different species of plants under the same name (Ligaa et al., 2005). That is, an ethno-species is much bigger than a natural species. Researchers in Inner Mongolia have noted that the folk names of plants are based on observations and understanding of the wild plants that grow in their desert environment (Khasbagan et al., 2000; Khasbagan and Soyolt, 2008), and that the high correlation between folk names and scientific names reflects the scientific meaning of folk botanical names and classifications (Ligaa et al., 2005). Complex primary names consist of two Mongol words. Some complex primary names include a word which indicates the life form. Caragana spinosa grows taller for camels, Caragana pygmaea is short for goats, and Caragana leucophloea is known for its golden stems. In Umnugobi Province, we also found similar names used by the local herders.

Our paper provided a comprehensive list of plants associated with Cistanche deserticola in South Gobi of Mongolia. Information presented in this study, especially the host plants of C. deserticola, would be valuable to understand this important plant community. Then conservation strategies may be made to effectively protect the rare and endangered species, C. deserticola, and the plant community as a whole.

The folk nomenclature of plants was formed gradually based on the local people's knowledge about plants and their ecological environments. It not only reflects how people describe a plant "species" and its natural ecosystem, but also relates it to its traditional uses. A recent study revealed that local people understood the habitat difference of different ethno-taxa of Acorus (Cheng et al., 2020). In the present study, there is also rich ethnoecological information in the Cistanche deserticola-associated community. The morphological and ecological features of plants are the most frequently used terms in the folk nomenclature. The ethnoecological implication of folk nomenclature is valuable for understanding the plant community and conserving plant diversity in Umnugobi Province, and other parts of Mongolia.

As a part of traditional botanical knowledge, the folk names of plants in the Cistanche community implied local people's wisdoms. The nomenclature was mostly originated from their morphological, color and sensory characters, or uses. The local people understand the relationships between C. deserticola and its associated species. It is essential to document such traditional knowledge associated with plant biodiversity. Thus, biodiversity conservation, taking its associated traditional knowledge as a whole, will be well-implemented according to the Convention on Biological Diversity.

5. ConclusionIn this study, we recorded six folk names for C. deserticola in Umnugobi Province, South Gobi of Mongolia. Six developmental stages of C. deserticola (bud flower, inflorescence emergence, flowering, end blooming, senescence and beginning of dormancy) were found. The local herders in southern Mongolia named four flowering stages with different folk names.

We recorded 96 species in 26 families and 71 genera from the Cistanche community in Umnugobi Province. These plants have been named by morphological characteristics, original place, name in memory of botanist or author, color of plant part, and traditional uses in southern Mongolia. There are some similarities between folk and binominal nomenclature, according to our case study. Many folk names in Umnugobi Province are from the colors of plant parts, i.e. leaves, stems, flowers, fruits, and others. The sensory character has commonly used to name plants in the Cistanche community.

Our study provided essential information for biodiversity conservation through documentation of traditional knowledge including folk nomenclature. Conservation strategy will be proposed to protect C. deserticola and other species in the plant community in South Gobi of Mongolia.

Author contributionsConceptualization, C.L., and A.B.; methodology, C.L. and U.M.; investigation, U.M., M.B., D.G., T.A., Z.A.; data analysis, U.M., Z.A., T.A., D.G. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, U.M. and T.A.; writing—review and editing, C.L.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, A.B., C.L. and U.M.; funding acquisition, C.L., and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AcknowledgementsThis research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31761143001, 31870316), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (7202109), Minzu University of China (KLEM-ZZ201904, KLEM-ZZ201906, YLDXXK20 1819), the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China (2019HB2096001006), Jiansheng Fresh Herb Medicine R & D Foundation (JSYY-20190101-043), and the Ministry of Education of China (B08044). Colleagues and Dr. Bayartungalag from the institute of Geography and Geoecology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences provided assistances in the field surveys. Yingjie Song at Minzu University of China provided useful comments. We are grateful to all of them.

Appendix A. Supplementary dataSupplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7.

APG IV, 2016. An update of the angiosperm phylogeny group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants. Bot. J. Linn. Soc, 181: 1-20. DOI:10.1111/boj.12385 |

Banzragch, D., Luvsanjav, Choi, 1965. Dictionary of Terminology of Mongolian Plants. State publishing house, Ulaanbaatar, p. 14.

|

Cheng Z., Shu H., Zhang S., et al, 2020. From folk taxonomy to species confirmation of Acorus (Acoraceae): evidences based on phylogenetic and metabolomic analyses. Front. Plant Sci, 11. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2020.00965 |

Gal J., 1972. Some of the characters of the gobi saxaul in Mongolian people's republic. Probl. Desert Dev, 3: 21-27. |

Gubanov I.A., 1996. Conspectus of the Flora of Outer Mongolia. "Valang" Press, Moscow, Russia.. Moscow, Russia: "Valang" Press.

|

Grubov, V. I., 1982. Key to Vascular Plants of Mongolia. Nauka, Leningrad, Russia.

|

Grubov, V. I., 2001. Key to the Vascular Plants of Mongolia. Science Publishers, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

|

Jiang Y., Tu P.F., 2009. Analysis of chemical constituents in Cistanche species. J. Chromatogr. A, 1216: 1970-1979. DOI:10.1016/j.chrome.2008.07.031 |

Khasbagan Huai, H. Y., Pei S. J., 2000. Wild plants in the diet of arhorchin Mongol herdsmen in inner Mongolia. Econ. Bot, 54: 528-536. DOI:10.2307/4256364 |

Khasbagan, Soyolt, 2008. Indigenous knowledge for plant species diversity: a case study of wild plants folk names used by the Mongolian in Ejina Desert, Inner Mongolia, PR. China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 4: 13. DOI:10.1186/17464269-4-2 |

Kobayashi H., Komatsu J., 1983. Constituents of cistanchis herba (1). J. Pharm. Soc. Jap, 103(5): 508. DOI:10.1248/yakushi1947.103.5_508 |

Khurelchuluun, B., Suran, D., Zina, S., 2007. Illustrated Guide of Raw Materials Used in Traditional Medicine. Erkhes Printing, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, pp. 1-32.

|

Li Z., Lin H., Gu L., et al, 2016. Herba Cistanche (Rou Cong-Rong): one of the best pharmaceutical gifts of traditional Chinese medicine. Front. Pharmacol, 7: 41. DOI:10.14336/AD.2017.0720 |

Li X., Zhang T. C., Qiao Q., et al, 2013. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of holoparasite Cistanche deserticola (Orobanchaceae) reveals gene loss and horizontal gene transfer from its host Haloxylon ammodendron (Chenopodiaceae). PloS One, 8: e58747. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0058747 |

Ligaa, U., Ochirbat, G., 2005. Ethnobotanical Dictionary (Latin e English e Mongolian-Russian), vol. 107. "Jinst Caragana" Press, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

|

Li Z. Y., Zhang C. H., Ren G. Y., et al, 2019. Ecological modeling of Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma in alxa. China. Sci. Rep, 9: 13134. DOI:10.1038/s41598019-48397-6 |

Ligaa, U., Davaasuren, B., Ninjil, N., 2006. Medicinal Plants of Mongolia Used in Western and Eastern Medicine. JCK Printing, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, pp. 1-448.

|

Loko L. E. Y., Toffa J., Adjatin A., et al, 2018. Folk taxonomy and traditional uses of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L. ) landraces by the sociolinguistic groups in the central region of the Republic of Benin. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 14: 52. DOI:10.1186/s13002-018-0251-6 |

Lun Z. R., Gasser R. B., Lai D. H., et al, 2005. Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China. Lancet Infect. Dis, 5: 31-41. DOI:10.1016/s1473-3099(04)01252-6 |

Manibazar, N., 2000. Urgamliin Duimin, vol. 2000. UB., p. 160(in Mongolian).

|

NSO (National Statistics Office of Mongolia), 2020. Mongolian Statistical Year Book. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

|

Phaka F. M., Netherlands E. C., Kruger D. J., et al, 2019. Folk taxonomy and indigenous names for frogs in Zululand, South Africa. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 15: 17. DOI:10.1186/s13002-019-0294-3 |

Sanchir, Ch, 1999. Inraspecifictaxa of Caragana microphylla lam. Grassland ecosystem management in the Mongolian planteau. Collection abstracts of symposium third world Academy of Sciences. Xilinhot 32-35.

|

Soyolt, Galsannorbu, Yongping, Wunenbayar, Liu G., et al, 2013. Wild plant folk nomenclature of the Mongol herdsmen in the Arhorchin national nature reserve, Inner Mongolia, PR China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 9: 30. DOI:10.1186/1746-4269-9-30 |

Tokuoka Y., Yamasaki F., Kimura K., et al, 2019. Tracing chronological shifts in farmland demarcation trees in southwestern Japan: implications from species distribution patterns, folk nomenclature, and multiple usage. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 15: 21. DOI:10.1186/s13002-019-0301-8 |

Turpin M., Si A., 2017. Edible insect larvae in Kaytetye: their nomenclature and significance. J. Ethnobiol, 37: 120-140. DOI:10.2993/0278-077137.1.120 |

Ulicsni, V., Svanberg, I., MolnA ar, Z., 2016. Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe-folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 12, 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7.

|

Ulziikhutag, N., 1984. Dictionary of Terminology of Mongolian Plants. State publishing house, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, p. 360(in Mongolian).

|

Ulziykhutag, N., 1985. Key to the Fodder Plants in the Pasture and Haymaking ofMongolia. State Publisher, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

|

Urgamal M., Gundegmaa V., Baasanmunkh Sh, et al, 2019. Additions to the vascular flora of Mongolia-IV. Proceedings of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences, 59: 41-53. DOI:10.5564/pmas.v59i2.1218 |

Urgamal M., Oyuntsetseg B., 2017. Atlas of the Endemic Vascular Plants of Mongolia. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: Bembi San Press.

|

Urgamal M., 2018. A catalogue of rare and threatened vascular plants of Mongolia. Botanical Issues of South Siberia and Mongolia, 17: 139-142. |

Village U., Khasbagan W., 2017. A preliminary investigation of wild plants used by the Mongols in Bairin Left Banner, Inner Mongolia, China: a case study in Chaganhad. J. Nature of Inner Asia, 1: 102-113. DOI:10.18101/25420623-2017-1-102-113 |

Wang T., Zhang L., Du Z.X., et al, 2019. Chemical diversity and prediction of potential cultivation areas of Cistanche herbs. Sci. Rep, 9: 19737. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-56379-x |

Wang T., Zhang X., Xie W., 2012. Cistanche deserticola Y. C Ma, "Desert ginseng": a review. Am. J. Chin. Med, 40: 1123-1141. DOI:10.1142/S0192415X12500838 |

Wang J., Seyler B.C., Ticktin T., et al, 2020. An ethnobotanical survey of wild edible plants used by the Yi people of Liangshan Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed, 16: 1-27. DOI:10.1186/s13002-0190349-5 |

Zhang, Z. Y., Tzvelev, N. N., 1998. Orobanchaceae. Flora of China, vol. 18. Science Press, Beijing, and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis, pp. 229-231.

|