扩展功能

文章信息

- 赵莹, 谢宇, 贺玺, 张艳, 魏溦, 李江

- ZHAO Ying, XIE Yu, HE Xi, ZHANG Yan, WEI Wei, LI Jiang

- 瓷烧结和不同数字制作技术对钴铬烤瓷冠适合性的影响

- Influence of porcelain firing and different manufacturing techniques in fit of Co-Cr porcelain crowns

- 吉林大学学报(医学版), 2018, 44(03): 548-552

- Journal of Jilin University (Medicine Edition), 2018, 44(03): 548-552

- 10.13481/j.1671-587x.20180317

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-11-28

钴铬烤瓷冠因其良好的生物相容性和机械性能被广泛应用于口腔修复领域[1]。边缘和内部适合性是影响修复体寿命的重要因素之一[2], 而影响修复体边缘及内部适合性的主要因素包括制作材料、制作技术和饰瓷烧结过程等[3]。针对不同的钴铬合金基底冠制作技术目前最常用的为传统失蜡铸造, 随着数字技术的飞速发展, 计算机辅助设计-计算机辅助制造技术(CAD/CAM)及3D打印技术也逐渐被引入到口腔领域, 电子技术因其相对费时少、工序少和节省材料等优点越来越受到重视[4]。精确度较高又不会对实验样品造成破坏的微计算机断层扫描技术(Micro-CT)法可通过建立2D/3D影像测量修复体具体数值[5], 但该方法较为昂贵目前应用并不多。目前国内外对于钴铬基底冠的边缘及内部适合性的研究较多, 但是对于钴铬合金基底冠上瓷后的变化及扫描不同模型的影响研究较少。本研究采用Micro-CT法测量不同制作技术和不同扫描对象制作的钴铬烤瓷冠饰瓷烧结前后适合性的差异, 为临床牙齿修复提供依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 主要材料和仪器钴铬合金金粉(Concept Laser公司, 德国), 切削钴铬合金预成块(Organic CoCr, R+K公司, 德国), 上瓷瓷粉(威兰德公司, 德国), 铸造蜡(BEGO公司, 德国), 塞拉格油泥型硅橡胶印模材料和高流动型轻体硅橡胶印模材料(DMG公司, 德国), 超硬石膏(Heraeus Kulzer公司, 美国)。扫描仪(ISCAN D104i, Imtetric 3D公司, 瑞士), 选择性激光打印机(Concept Laser公司, 德国), 树脂熔模打印机(3D System, 美国), 切削设备(Organical Multi & Change 20, R+K公司, 德国), 铸造机(Fornax, BEGO公司, 德国), Micro-CT影像系统(μCT50, SCANCO Medical AG公司, 瑞士), 维他4.0烤瓷炉(德国)。

1.2 标准全冠牙体预备选取5颗上颌第一前磨牙, 进行全冠牙体预备, 颊侧为宽2.0 mm的135°凹槽肩台, 领面舌面宽1.8 mm, 牙合面为2.0 mm, 轴面聚合度为5°。

1.3 电子文件(STL)的生成扫描预备后的离体牙、硅橡胶印模和石膏模型生成制作修复体需要的电子文件。

1.4 样本分组样本分为扫描离体牙3D打印激光熔覆凝结(SLM)组(tooth-SLM组)、硅橡胶印模3D打印SLM组(silicone rubber-SLM组)、石膏模型3D打印SLM组(stone die-SLM组)、扫描离体牙CAD/CAM切削组(tooth-CAD/CAM组)、硅橡胶印模CAD/CAM切削组(silicone rubber-CAD/CAM组)、石膏模型CAD/CAM切削组(stone die-CAD/CAM组), 以传统失蜡铸造组作为对照组。

1.5 轻体硅橡胶复制间隙利用轻体硅橡胶替代粘接剂复制修复体与基牙之间的间隙, 采用50 N模拟口腔中修复体粘接过程中的作用力使修复体就位[6]。

1.6 Micro-CT扫描和SCANCO Medical System软件重建Micro-CT扫描参数:70 kvp、200μA、300 ms, 1 024×1 024像素。扫描完成后采用SCANCO Medical System软件进行三维及二维重建。

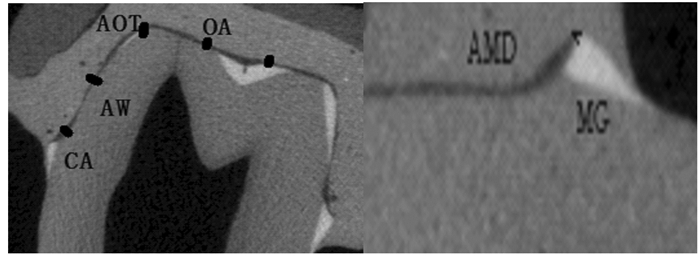

1.7 修复体内部和边缘适合性检测内部适合性:2个凹槽区(CA, 距预备体边缘约0.8 mm), 2个轴壁中点(AW), 2个轴壁与牙合面转角的位置(AOT), 2个牙合面三分位点(OA); 边缘适合性:2个绝对边缘差异(AMD), 2个边缘间隙(MG)[7]。见图 1。

|

| 图 1 Micro-CT 2D图像上边缘和内部适合性的测量位点 Figure 1 Measuring points of marginal and internal fits on Micro-CT 2D images |

|

|

上瓷过程为950℃~1 010℃真空下遮色瓷、体瓷、透明瓷和釉瓷分别循环烧结。

1.9 统计学分析采用SPSS16.0统计软件进行统计学分析。各组牙齿修复体边缘适合性和内部适合性组间比较采用方差分析, 上瓷过程前后修复体适合性比较采用配对t检验。双侧α=0.05为检验水准。

2 结果 2.1 各组修复体的边缘和内部适合性与对照组比较, 扫描离体牙硅橡胶印模3D打印SLM组及CAD/CAM切削组修复体AMD降低(P<0.05);与对照组比较, 3D打印SLM组修复体MG明显降低, 尤以硅橡胶印模3D打印SLM组最小(P<0.05)。与对照组比较, 硅橡胶印模3D打印SLM组修复体CA和AW明显降低(P<0.05), 以扫描离体牙CAD/CAM切削组修复体AW最小。与对照组比较, 石膏模型3D打印SLM组和CAD/CAM切削组修复体AOT和OA减少(P<0.05), 以硅橡胶印模CAD/CAM切削组修复体AOT和OA最小。见表 1。

| (n=5, x±s) | |||||||

| Group | Marginal fit(l/μm) | Internal fit(l/μm) | |||||

| AMD | MG | CA | AW | AOT | OA | ||

| Control | 162.1±14.7 | 106.4±16.1 | 127.2±14.2 | 95.0±4.4 | 129.8±8.5 | 158.6±5.9 | |

| Tooth-SLM | 133.2±14.8* | 94.9±3.7 | 136.1±21.3 | 81.6±15.6 | 160.0±13.7 | 248.5±10.3* | |

| Silicone rubber-SLM | 125.7±10.7* | 91.3±6.7* | 105.2±10.6* | 86.3±7.5* | 130.8±38.6 | 171.3±16.9 | |

| Stone die-SLM | 146.7±22.3 | 99.6±11.7 | 132.6±8.0 | 86.5±15.1 | 169.9±23.8* | 251.3±35.0* | |

| Tooth-CAD/CAM | 125.9±14.9* | 99.8±12.1 | 116.3±6.3 | 80.4±6.3* | 111.5±15.2* | 133.5±12.9* | |

| Silicone rubber-CAD/CAM | 126.5±8.7* | 96.0±4.6 | 119.1±12.3 | 81.8±11.0* | 108.3±3.5* | 120.6±11.9* | |

| Stone die-CAD/CAM | 131.2±11.1* | 111.2±9.6 | 123.2±10.3 | 93.4±5.1 | 128.6±11.7 | 165.1±15.9 | |

| * P < 0.05 vs control group. | |||||||

与瓷烧结前比较, 瓷烧结后修复体边缘和内部适合性普遍升高(P < 0.05)。见图 2。

|

| *P < 0.05 vs before porcelain firing. 图 2 上瓷前和上瓷后修复体边缘和内部适合性 Figure 2 Marginal and internal fits of restorations before and after porcelain firing |

|

|

双因素方差分析显示:MG与制作工艺和扫描对象有关联(P < 0.05), 内部适合性平均数与制作工艺和扫描对象有密切关联(P < 0.05)。见表 2。

| Factor | Marginal fit | Internal fit | ||||||

| AMD | MG | CA | AW | AOT | OA | Average | ||

| Fabricated techniques | 0.178 | 0.039 | 0.273 | 0.092 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Scanning objects | 0.142 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.198 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Fabricated techniques *scanning objects | 0.464 | 0.569 | 0.017 | 0.492 | 0.371 | 0.004 | 0.013 | |

边缘和内部适合性不仅是影响修复体寿命的重要因素之一, 而且也是评价其是否成功的标准。过大的边缘适合性导致粘接剂溶解, 间接导致继发龋、牙髓炎、牙髓坏死和牙周问题[8], 而不良内部适合性将导致牙冠内部受力不均及应力集中[9]。Castillo-Oyagüe等[10]研究显示:研究微渗漏与边缘适合性呈微弱正相关关系, 所以对于边缘及内部适合性的研究对微渗漏的研究也有一定的促进作用。Micro-CT作为可量化测量适合性变化的方法因其成本较高而未得到广泛应用, 本研究中采用该方法可避免破坏修复体并保证精确度[11]。随着科学技术的飞速发展, 关于钴铬烤瓷冠的制作工艺也越来越多, 如传统的失蜡铸造和现代的CAD/CAM及3D打印技术[12], 研究[13]显示临床可接受的边缘适合性中MG为120μm, 本实验中各组修复体边缘适合性中MG均小于120μm, 表明3D打印SLM组修复体边缘适合性与CAD/CAM切削组相差无几。而CAD/CAM组内部适合性较优越, 原因可能与金属粉末熔融过程中内部缺少气载分子的摩擦有关; 传统失蜡铸造因人为因素较多, 导致其精确性降低[14]。

影响修复体精确性的因素中印模材料的选择和制取很重要, 目前电子扫描获得的数字模型的精确性少有研究。本研究比较扫描预备牙体、硅橡胶印模和石膏模型后制作修复体的精确度, 结果显示:在3D打印SLM组和CAD/CAM组硅橡胶印模精确性较高, 证明其是一种性能较好的印模材料。原因可能在于CAD/CAM的扫描原理是利用激光3D摄像头, 拍摄到物体的影像数据, 通过点和线的位置计算合成物体的轮廓并输出[15], 直接扫描预备体时, 因牙体组织较光滑反射光线较强, 无法保证扫描精度, 需要喷扫描粉, 喷粉的过程及牙体组织本身光滑反射光线的情况均可能带来准确性的偏差[16]。因本实验采用离体牙体外扫描, 难以模拟相对复杂的口内环境, 也会造成该实验的局限[17]。

本实验新增加的硅橡胶材料属于加聚型聚硅醚, 研究[18]显示:硅橡胶材料精确度较高, 不易变形并且脱离口腔环境后温度及湿度对其影响较小, 而扫描的石膏模型灌制的标准化过程参差不齐、灌制模型过程中的小气泡和触碰等均会对石膏模型造成不易察觉的变化, 影响扫描后模型的精确性, 表明不同的制作技术及扫描不同的对象均会对修复体的适合性产生不同程度的影响。本研究结果为以后提高修复体精确性及对技术的选择提供了依据。

瓷烧结过程为真空下高温环境的往复循环, 研究[19]表明这种高温过程不仅影响其表面微结构及抗腐蚀性, 并且影响边缘适合性, 但相关研究并不多见。本研究结果显示:瓷烧结过程使修复体边缘及内部适合性均增大, 与瓷烧结前比较差异有统计学意义, 原因可能为高温度过程。不仅影响材料的微结构, 还会产生金属蠕变[20]。

综上所述, 瓷烧结过程会增大修复体的边缘和内部适合性, 3D打印SLM组修复体的边缘适合性优于其他技术, CAD/CAM组修复体内部适合性是目前技术中最佳的, 硅橡胶印模对修复体适合性的精确性影响最小。

| [1] | Kane LM, Chronaios D, Sierraalta M, et al. Marginal and internal adaptation of milled cobalt-chromium copings[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2015, 114(5): 680–685. DOI:10.1016/j.prosdent.2015.04.020 |

| [2] | Quante K, Ludwig K, Kern M. Marginal and internal fit of metal-ceramic crowns fabricated with a new laser melting technology[J]. Dent Mater, 2008, 24(10): 1311–1315. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2008.02.011 |

| [3] | Naveen HC, Pillai LK, Porwal A, et al. Effect of porcelain-firing cycles and surface finishing on the marginal discrepancy of titanium copings[J]. J Prosthodont, 2011, 20(2): 101–105. DOI:10.1111/jopr.2011.20.issue-2 |

| [4] | Ucar Y, Akova T, Akyil MS, et al. Internal fit evaluation of crowns prepared using a new dental crown fabrication technique:laser-sintered Co-Cr crowns[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2009, 102(4): 253–259. DOI:10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60165-7 |

| [5] | Hindelang F, Zurbach R, Roggo Y. Micro computer tomography for medical device and pharmaceutical packaging analysis[J]. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2015, 108: 38–48. DOI:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.01.045 |

| [6] | Laurent M, Scheer P, Dejou J, et al. Clinical evaluation of the marginal fit of cast crowns—validation of the silicone replica method[J]. J Oral Rehabil, 2008, 35(2): 116–122. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2003.01203.x |

| [7] | Borba M, Cesar PF, Griggs JA, et al. Adaptation of all-ceramic fixed partial dentures[J]. Dent Mater, 2011, 27(11): 1119–1126. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2011.08.004 |

| [8] | Kale E, Yilmaz B, Seker E, et al. Effect of fabrication stages and cementation on the marginal fit of CAD-CAM monolithic zirconia crowns[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2017, 118(6): 736–741. DOI:10.1016/j.prosdent.2017.01.004 |

| [9] | Mously HA, Finkelman M, Zandparsa R, et al. Marginal and internal adaptation of ceramic crown restorations fabricated with CAD/CAM technology and the heat-press technique[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2014, 112(2): 249–256. DOI:10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.03.017 |

| [10] | Castillo-Oyagüe R, Lynch CD, Turrión AS, et al. Misfit and microleakage of implant-supported crown copings obtained by laser sintering and casting techniques, luted with glass-ionomer, resin cements and acrylic/urethane-based agents[J]. J Dent, 2013, 41(1): 90–96. DOI:10.1016/j.jdent.2012.09.014 |

| [11] | Borba M, Miranda WG Jr, Cesar PF, et al. Evaluation of the adaptation of zirconia-based fixed partial dentures using micro-CT technology[J]. Braz Oral Res, 2013, 27(5): 396–402. DOI:10.1590/S1806-83242013000500003 |

| [12] | Xin XZ, Chen J, Xiang N, et al. Surface characteristics and corrosion properties of selective laser melted Co-Cr dental alloy after porcelain firing[J]. Dent Mater, 2014, 30(3): 263–270. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2013.11.013 |

| [13] | McLean JW, von Fraunhofer JA. The estimation of cement film thickness by an in vivo technique[J]. Br Dent J, 1971, 131(3): 107–111. DOI:10.1038/sj.bdj.4802708 |

| [14] | Sundar MK, Chikmagalur SB, Pasha F. Marginal fit and microleakage of cast and metal laser sintered copings-an in vitro study[J]. J Prosthodont Res, 2014, 58(4): 252–258. DOI:10.1016/j.jpor.2014.07.002 |

| [15] | Lambert H, Durand JC, Jacquot B, et al. Dental biomaterials for chairside CAD/CAM:State of the art[J]. J Adv Prosthodont, 2017, 9(6): 486–495. DOI:10.4047/jap.2017.9.6.486 |

| [16] | Mously HA, Finkelman M, Zandparsa R, et al. Marginal and internal adaptation of ceramic crown restorations fabricated with CAD/CAM technology and the heat-press technique[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2014, 112(2): 249–256. DOI:10.1016/j.prosdent.2014.03.017 |

| [17] | Sakornwimon N, Leevailoj C. Clinical marginal fit of zirconia crowns and patients' preferences for impression techniques using intraoral digital scanner versus polyvinyl siloxane material[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2017, 118(3): 386–391. DOI:10.1016/j.prosdent.2016.10.019 |

| [18] | Martins F, Branco P, Reis J, et al. Dimensional stability of two impression materials after a 6-month storage period[J]. Acta Biomater Odontol Scand, 2017, 3(1): 84–91. DOI:10.1080/23337931.2017.1401933 |

| [19] | Shokry TE, Attia M, Mosleh I, et al. Effect of metal selection and porcelain firing on the marginal accuracy of titanium-based metal ceramic restorations[J]. J Prosthet Dent, 2010, 103(1): 45–52. DOI:10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60216-X |

| [20] | Patil A, Singh K, Sahoo S, et al. Comparative assessment of marginal accuracy of grade Ⅱ titanium and Ni-Cr alloy before and after ceramic firing:An in vitro study[J]. Eur J Dent, 2013, 7(3): 272–277. DOI:10.4103/1305-7456.115409 |

2018, Vol. 44

2018, Vol. 44