扩展功能

文章信息

- 昝晓燕, 吴贻刚

- 趋化因子配体19和趋化因子受体7在肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症中的作用及有氧运动对其影响的研究进展

- Research progress in role of CCL19 and CCR7 in adipose tissue chronic in flammation and influence of aerobic exercise in CCL19-CCR signal

- 吉林大学学报(医学版), 2017, 43(03): 659-662

- Journal of Jilin University (Medicine Edition), 2017, 43(03): 659-662

- 10.13481/j.1671-587x.20170339

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-06-22

趋化因子受体7(C-C chemokine receptor 7, CCR7) 信号通路的主要功能有趋化性、细胞黏附与整合能力、免疫细胞增殖与分化等[1-4]。CCR7信号的异常变化不仅会引发即时免疫应答,还可能导致长期的慢性炎症反应[1]。肥胖是一种以全身脂肪组织增多为特征的代谢性疾病,机体脂肪含量与外周低度、慢性炎症的发生有密切关联[5-6],而慢性炎症对肥胖相关的胰岛素抵抗具有明显的促进作用[6]。研究[5, 7-10]表明:肥胖者脂肪组织的多种炎症因子如肿瘤坏死因子α(tumor necrosis factor-α,TNF-α)和白细胞介素6(interleukin-6,IL-6) 表达水平升高,同时脂肪组织促炎性巨噬细胞、T细胞和树突状细胞数量均有增多,但对这些炎症因子和免疫细胞增多的机制报道并不多。近年研究[11]显示:CCR7在肥胖脂肪组织免疫细胞招募和聚集过程中起重要的促进作用,该过程促成了脂肪组织慢性炎症反应和胰岛素抵抗的产生。目前尚无关于CCR7信号在肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症中机制的总结和概述。因此,本文以趋化因子配体19(chemoking ligand, CCL19) 和CCR7信号通路为中介,总结了在肥胖脂肪组织中该信号的发现过程,并对其介导慢性炎症和胰岛素抵抗的机制进行综述,探讨有氧运动通过抑制该信号来改善肥胖的可能机制,从而提出肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症形成的新机制并给出运动改善肥胖的潜在作用靶点。

1 CCR7信号通路CCR7是一种含有7次跨膜结构域的G蛋白耦联受体,通过位于细胞外的N末端与其2个配体CCL19和CCL21结合来发挥生理学效应[4]。CCR7在树突状细胞(dendritic cells,DCs)、巨噬细胞、B细胞、天然调节性T细胞、调节性T细胞和记忆T细胞中均有表达。CCL19和CCL21表达于富含T细胞的淋巴结区域内的基质细胞,在淋巴细胞向次级淋巴组织归巢中起重要的趋化作用[4]。趋化性是CCR7功能轴在适应性免疫中最主要的功能。CCR7信号可介导DCs和T淋巴细胞向次级淋巴组织归巢,并指引T细胞在次级淋巴组织中的定向移动和分区聚集[12]。但CCL21和CCL19与CCR7的结合既有协同又有竞争关系,生理浓度的CCL21可趋化外周血T细胞,但CCL19却不能。由于两者与CCR7的亲和力不同,在CCL21存在时,T细胞会远离CCL19而向CCL21浓度方向移动,这体现了两者的竞争关系[2]。此外,CCR7信号对细胞黏附与整合、分化、生长、存活、内吞、迁移速率与侵袭能力均有一定影响。CCR7信号在自然免疫过程中的功能多样性为其参与多种疾病的发生发展提供了基础。

2 肥胖与慢性炎症肥胖已成为全球性威胁人类健康的问题之一,被世界卫生组织(World Health Organization, WHO)列为导致疾病负担的十大危险因素之一。国家体育总局的研究[13]结果显示:2000—2014年各年龄段成年人肥胖发生率均处于上升趋势;年龄越大,肥胖发生概率越高;2014年全国成年人平均肥胖发生率为12.9%。由肥胖引发的代谢紊乱性疾病将给社会带来沉重的医疗负担。按照病因分型,肥胖可分为单纯性肥胖和继发性肥胖,单纯性肥胖约占肥胖总数的95%。该类肥胖主要是由于摄入的能量总量与身体消耗的总能量不平衡造成的,伴随能量失衡的是全身多器官慢性炎症。首先,长期营养过剩通过作用于代谢细胞(如脂肪细胞),引发炎症反应,随后对能量代谢稳态产生影响[14]。自首个炎症因子TNF-α在小鼠脂肪组织中被发现和报道[15]后,众多细胞因子如IL-6、白细胞介素1β(interleukin-1β,IL-1β)和趋化因子配体2(chemokine, ligand2, CCL2) 等也相继在肥胖相关脂肪组织、肝脏、胰腺、骨骼肌和大脑中被发现,但内脏脂肪组织更可能是炎症引发的胰岛素抵抗的最早起始点[16]。这些炎症因子并不像感染、创伤所引起急性炎症因子水平升高,而是表现为中度的、局部性的炎症因子表达水平升高[14]。其次,由能量过剩引发的代谢组织炎症反应对免疫细胞定向迁移起重要作用。动物实验和人体实验[14, 17-18]表明:脂肪组织促炎性巨噬细胞(M1型)、CD8+T细胞、DCs数量均增多;而抗炎性巨噬细胞(M2型)、调节性T细胞(Treg)、Th2细胞数量却减少。这种免疫细胞的失衡改变了原有的抗炎微环境状态,为局部免疫应答创造了条件。

尽管高糖、低氧、内质网应激、细胞损伤和死亡均可能是肥胖过程中的炎症介导者[18],但长期营养过剩很可能是肥胖慢性炎症反应的最初启动因素。过度营养产生的饱和脂肪酸(saturated fatty acid, SFA)可能对引发起始炎症反应有重要作用。研究[19]表明:高脂膳食(high fat diet, HFD)主要成分SFA可直接激活大鼠脑组织Toll样受体4(Toll-like receptor 4, TLR4) 信号而引发炎症反应;当TLR4被阻断后,瘦素信号、食欲、体质量异常和糖代谢紊乱均得以改善。SFA引发的脂肪组织TLR4表达水平上调可促使炎症因子释放,并导致骨骼肌胰岛素抵抗[20]。SFA还可以激活M1巨噬细胞和胰腺β细胞等从而引发炎症反应[21-22]。越来越多的研究[23-25]证实:SFA在肥胖慢性炎症形成过程中可通过激活不同信号引发局部炎症以及胰岛素抵抗。SFA可通过激活CCR7+脂肪组织巨噬细胞(adipose tissue macrophage, ATM)而介导肥胖慢性炎症形成过程[11],这为研究CCR7信号与肥胖慢性炎症的关系提供了依据。

3 CCR7信号与肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症研究者[26]早期采用微阵列基因芯片观察HFD诱导的KKAy小鼠腹部脂肪组织细胞因子表达情况发现:CCL19和CCR7表达水平均升高,但CCL21表达水平却不变;RT-PCR法进一步验证了前两者在转录水平上表达的上调。随后的研究[27]确证了在人体和动物脂肪细胞中,TNF-α对CCL19的转录活化作用。研究[28]显示:肥胖人群血清CCL19水平与体质量指数(BMI)存在一定的相关性,提示CCL21-CCR7信号比CCL19-CCR7信号在肥胖慢性炎症中的作用可能更为重要,而CCL19可能是由炎症微环境中的脂肪细胞所分泌的。

研究[29]显示:外源性内毒素可上调肥胖C57BL/6J小鼠血清CCL19水平,针对CCR7基因敲除后发现,HFD引起的肥胖、脂肪肝、血脂紊乱和胰岛素抵抗均得以改善;同时,脂肪组织DCs标志CD11c和多种炎症因子(如Mcp-1/CCL2、IL-6和TNF-α)表达水平均下调,但脂联素(adiponectin)水平却升高。研究[30]显示:CCR7-/-肥胖小鼠脂肪组织中DCs数量减少的同时伴随着局部炎症的减轻和胰岛素抵抗的改善。TNF-α和LPS协同上调3T3脂肪细胞分泌CCL19。研究[30]显示:在冷暴露条件下,CCR7-/-小鼠产热明显增多,并且附睾脂肪组织解偶联蛋白1(uncoupling protein-1, UCP-1)、UCP-2和Cidea转录表达水平明显升高,提示在肥胖进程中,CCR7的可能作用为:一方面趋化DCs至脂肪组织,该过程可能引发的效应为促进巨噬细胞向脂肪组织迁移[31],体质量增加、胰岛素抵抗和糖脂代谢异常[31-32],刺激促炎性Th17细胞分化[32];另一方面通过降低脂肪组织关键代谢因子(UCP-1、UCP-2和Cidea)来促进肥胖慢性炎症形成。当CCR7被抑制后,肥胖及慢性炎症现象均得以改善,但其中的具体机制仍需进一步实验验证。

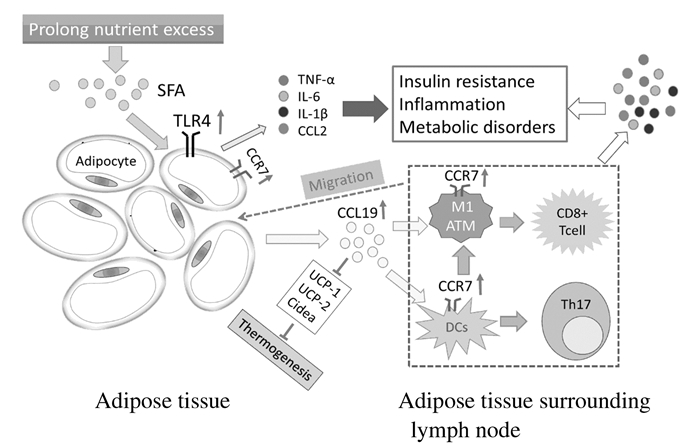

研究[11]显示:在肥胖内脏脂肪组织周围的淋巴结中,CCR7+ CD11c+ DCs和巨噬细胞数量明显增加,这种CCR7+免疫细胞的聚集促进了局部炎症和胰岛素抵抗形成;当CCR7被敲除后,脂肪组织DCs、M1巨噬细胞,CD8+T细胞和B细胞数量均明显下降,并且胰岛素抵抗和糖耐受明显改善,鉴于CCR7在趋化抗原提呈细胞向淋巴结迁移中的作用[12],本文作者认为:CCR7 -/-小鼠M1 ATM减少引起了CD8+ T细胞和B细胞向脂肪组织的迁移,减少了炎症因子形成并改善胰岛素信号。对肥胖小鼠使用抗CCR7抗体治疗取得了与CCR7-/-肥胖小鼠类似的结果 [11]。CCR7同样表达于具有脂质转运功能的ATM[33-34],研究[34-35]显示:SFA可刺激小鼠脂肪巨噬细胞分泌炎症因子TNF-α,TNF-α可上调CCR7 mRNA和细胞膜蛋白水平,ATM向脂肪组织附近的淋巴结迁移是以CCR7依赖的方式进行,CCR7-/-小鼠血清CCL2水平下降、CD11c+ DCs减少、M1 ATM减少并伴随TNF-α水平的下调,而后者是胰岛素信号的直接抑制剂[14]。ATM表达的Ⅱ类主要组织相容性复合体(MHCⅡ)和共刺激因子(CD40和CD80) 对于CD4+T细胞增殖和向淋巴结聚集具有重要作用[36-37],因此,CCR7缺陷引发的ATM迁移减少打破了促炎微环境,改善了局部免疫状态。CCR7在诱导肥胖慢性炎症和胰岛素抵抗中的可能作用见图 1。

|

| 图 1 CCR7在肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症和胰岛素抵抗形成中可能作用的示意图 Figure 1 Schematic diagram of possible roles of CCR7 in obesity adipose tissue chronic inflammation and insulin resistance |

|

|

有氧运动既可以减轻肥胖者的脂肪含量,又可以明显改善脂肪组织胰岛素抵抗和局部炎症状态[38]。除了IL-6、TNF-α、IL-1β和CCL2等众所周知的炎症因子在肥胖者脂肪组织中有表达,趋化因子如CXCL5、CXCL14、单核细胞趋化因子1(monocyte chemotactic protein-1,MCP-1) 以及CCL19等在肥胖者体内表达水平亦升高[26, 28]。长期有氧运动改善肥胖脂肪含量和慢性炎症的机制可能有:① 减少SFA在脂肪组织聚集,增加SFA氧化分解;② 循环SFA下降减弱了其对脂肪细胞和巨噬细胞TLR4的活化,从而减少促炎症因子分泌[20, 39];③ 促进抗炎因子分泌,改善局部免疫微环境,使得抗炎性免疫细胞占优势[40-41]。研究[41]表明:长期慢性运动可增加脂肪细胞NK细胞数量和IL-6分泌;而30%的卡路里限制可增加CD4+/CD8+细胞比例和MCP-1分泌水平。对于肥胖模型小鼠,运动训练可减弱M1巨噬细胞和CD8+ T淋巴细胞向脂肪组织浸润[42]。对于肥胖人群,有氧训练可增加外周血树突状细胞抗原1(blood dendritic cells antigen-1,BDCA-1)、TLR-4和TLR-7的表达,这种变化对增加免疫抵抗、降低体质量和改善血脂紊乱有促进作用[43]。结合上述CCR7在脂肪细胞、巨噬细胞和DCs中的表达及其在介导肥胖慢性炎症中的作用,本文作者推测:长期有氧运动对肥胖机体CCL19-CCR7信号的可能影响为:① 减弱SFA对CCR7+巨噬细胞和DCs的激活,从而改善局部炎微环境;② 降低CCR7在免疫细胞表面的表达,弱化其特异性反应过程;③ 减弱包括CCL19在内的多种促炎性趋化因子水平,从而减轻炎症并改善胰岛素抵抗。

综上所述,肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症与免疫功能紊乱关系密切。CCR7信号作为天然免疫的重要分子,其在肥胖慢性炎症中作用才被认识。肥胖脂肪组织CCL19-CCR7信号的上调对炎症因子分泌和多种免疫细胞招募起促进作用,同时抑制了脂肪分解代谢过程,加剧慢性炎症反应和胰岛素抵抗。结合有氧运动的减脂和改善局部炎症效果,本文作者推测:长期运动对CCL19-CCR7信号的负向调控可改善脂肪组织的促炎-抗炎微环境,同时改善脂代谢和胰岛素抵抗状态。更多针对CCL19-CCR7信号的研究将为预防和治疗肥胖脂肪组织慢性炎症提供依据。

| [1] | Moschovakis GL, Forster R. Multifaceted activities of CCR7 regulate T-cell homeostasis in health and disease[J]. Eur J Immunol, 2012, 42(8): 1949–1955. DOI:10.1002/eji.v42.8 |

| [2] | Nandagopal S, Wu D, Lin F. Combinatorial guidance by CCR7 ligands for T lymphocytes migration in co-existing chemokine fields[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(3): e18183. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0018183 |

| [3] | Ziegler E, Oberbarnscheidt M, Bulfone-Paus S, et al. CCR7 signaling inhibits T cell proliferation[J]. J Immunol, 2007, 179(10): 6485–6493. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6485 |

| [4] | Sanchez-Sanchez N, Riol-Blanco L, Rodriguez-Fernandez JL. The multiple personalities of the chemokine receptor CCR7 in dendritic cells[J]. J Immunol, 2006, 176(9): 5153–5159. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5153 |

| [5] | Paniagua JA. Nutrition, insulin resistance and dysfunctional adipose tissue determine the different components of metabolic syndrome[J]. World J Diabetes, 2016, 7(19): 483–514. DOI:10.4239/wjd.v7.i19.483 |

| [6] | Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance[J]. J Clin Invest, 2003, 112(12): 1821–1830. |

| [7] | Bullo M, Garcia-Lorda P, Megias I, et al. Systemic inflammation, adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor, and leptin expression[J]. Obes Res, 2003, 11(4): 525–531. DOI:10.1038/oby.2003.74 |

| [8] | Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue[J]. J Clin Invest, 2003, 112(12): 1796–1808. DOI:10.1172/JCI200319246 |

| [9] | Prieur X, Mok CY, Velagapudi VR, et al. Differential lipid partitioning between adipocytes and tissue macrophages modulates macrophage lipotoxicity and M2/M1 polarization in obese mice[J]. Diabetes, 2011, 60(3): 797–809. DOI:10.2337/db10-0705 |

| [10] | Deiuiis J, Shah Z, Shah N, et al. Visceral adipose inflammation in obesity is associated with critical alterations in tregulatory cell numbers[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(1): e16376. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0016376 |

| [11] | Hellmann J, Sansbury BE, Holden CR, et al. CCR7 maintains nonresolving lymph node and adipose inflammation in obesity[J]. Diabetes, 2016, 65(8): 2268–2281. DOI:10.2337/db15-1689 |

| [12] | Forster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands:balancing immunity and tolerance[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2008, 8(5): 362–371. DOI:10.1038/nri2297 |

| [13] | Tian Y, Jiang C, Wang M, et al. BMI, leisure-time physical activity, and physical fitness in adults in China:results from a series of national surveys, 2000-14[J]. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2016, 4(6): 487–497. DOI:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00081-4 |

| [14] | Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2011, 29(29): 415–445. |

| [15] | Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, et al. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance[J]. J Clin Invest, 1995, 95(5): 2409–2415. DOI:10.1172/JCI117936 |

| [16] | Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance[J]. J Clin Invest, 2006, 116(7): 1793–1801. DOI:10.1172/JCI29069 |

| [17] | Han JM, Levings MK. Immune regulation in obesity-associated adipose inflammation[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 191(2): 527–532. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1301035 |

| [18] | Deng T, Lyon CJ, Bergin S, et al. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer[J]. Annu Rev Pathol, 2016, 11: 421–449. DOI:10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044359 |

| [19] | Milanski M, Degasperi G, Coope A, et al. Saturated fatty acids produce an inflammatory response predominantly through the activation of TLR4 signaling in hypothalamus:implications for the pathogenesis of obesity[J]. J Neurosci, 2009, 29(2): 359–370. DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2760-08.2009 |

| [20] | Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, et al. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance[J]. J Clin Invest, 2006, 116(11): 3015–3025. DOI:10.1172/JCI28898 |

| [21] | Boden G, Shulman GI. Free fatty acids in obesity and type 2 diabetes:defining their role in the development of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction[J]. Eur J Clin Invest, 2002, 32(Suppl 3): 14–23. |

| [22] | Iyer A, Fairlie DP, Prins JB, et al. Inflammatory lipid mediators in adipocyte function and obesity[J]. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 2010, 6(2): 71–82. DOI:10.1038/nrendo.2009.264 |

| [23] | Salvado L, Coll T, Gomez-Foix AM, et al. Oleate prevents saturated-fatty-acid-induced ER stress, inflammation and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells through an AMPK-dependent mechanism[J]. Diabetologia, 2013, 56(6): 1372–1382. DOI:10.1007/s00125-013-2867-3 |

| [24] | Gadang V, Kohli R, Myronovych A, et al. MLK3 promotes metabolic dysfunction induced by saturated fatty acid-enriched diet[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2013, 305(4): E549–556. DOI:10.1152/ajpendo.00197.2013 |

| [25] | Ordelheide AM, Gommer N, Bohm A, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF):A saturated fatty acid-induced myokine with insulin-desensitizing properties in humans[J]. Mol Metab, 2016, 5(4): 305–316. DOI:10.1016/j.molmet.2016.02.001 |

| [26] | Lee HS, Park JH, Kang JH, et al. Chemokine and chemokine receptor gene expression in the mesenteric adipose tissue of KKAy mice[J]. Cytokine, 2009, 46(2): 160–165. DOI:10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.025 |

| [27] | Tourniaire F, Romier-Crouzet B, Lee JH, et al. Chemokine expression in inflamed adipose tissue is mainly mediated by NF-kappaB[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e66515. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0066515 |

| [28] | Kitahara CM, Trabert B, Katki HA, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and serum markers of inflammation, immunity, and insulin resistance[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2014, 23(12): 2840–2849. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0699-T |

| [29] | Sano T, Iwashita M, Nagayasu S, et al. Protection from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice lacking CCL19-CCR7 signaling[J]. Obesity (Silver Spring), 2015, 23(7): 1460–1471. DOI:10.1002/oby.21127 |

| [30] | Cho KW, Zamarron BF, Muir LA, et al. Adipose tissue dendritic cells are independent contributors to obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance[J]. J Immunol, 2016, 197(9): 3650–3661. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1600820 |

| [31] | Stefanovic-Racic M, Yang X, Turner MS, et al. Dendritic cells promote macrophage infiltration and comprise a substantial proportion of obesity-associated increases in CD11c+ cells in adipose tissue and liver[J]. Diabetes, 2012, 61(9): 2330–2339. DOI:10.2337/db11-1523 |

| [32] | Bertola A, Ciucci T, Rousseau D, et al. Identification of adipose tissue dendritic cells correlated with obesity-associated insulin-resistance and inducing Th17 responses in mice and patients[J]. Diabetes, 2012, 61(9): 2238–2247. DOI:10.2337/db11-1274 |

| [33] | Xu X, Grijalva A, Skowronski A, et al. Obesity activates a program of lysosomal-dependent lipid metabolism in adipose tissue macrophages independently of classic activation[J]. Cell Metab, 2013, 18(6): 816–830. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.001 |

| [34] | Orr JS, Kennedy AJ, Hill AA, et al. CC-chemokine receptor 7(CCR7) deficiency alters adipose tissue leukocyte populations in mice[J]. Physiol Rep, 2016, 4(18): e12971. DOI:10.14814/phy2.12971 |

| [35] | Suganami T, Yuan X, Shimoda Y, et al. Activating transcription factor 3 constitutes a negative feedback mechanism that attenuates saturated Fatty acid/toll-like receptor 4 signaling and macrophage activation in obese adipose tissue[J]. Circ Res, 2009, 105(1): 25–32. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196261 |

| [36] | Morris DL, Cho KW, Delproposto JL, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages function as antigen-presenting cells and regulate adipose tissue CD4+ T cells in mice[J]. Diabetes, 2013, 62(8): 2762–2772. DOI:10.2337/db12-1404 |

| [37] | Cho KW, Morris DL, Delproposto JL, et al. An MHC Ⅱ-dependent activation loop between adipose tissue macrophages and CD4+ T cells controls obesity-induced inflammation[J]. Cell Rep, 2014, 9(2): 605–617. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.004 |

| [38] | Keshel TE, Coker RH. Exercise training and insulin resistance:a current review[J]. J Obes Weight Loss Ther, 2015, 5(Suppl 5): S5–L3. |

| [39] | Reyna SM, Ghosh S, Tantiwong P, et al. Elevated toll-like receptor 4 expression and signaling in muscle from insulin-resistant subjects[J]. Diabetes, 2008, 57(10): 2595–2602. DOI:10.2337/db08-0038 |

| [40] | Kawanishi N, Yano H, Mizokami T, et al. Exercise training attenuates hepatic inflammation, fibrosis and macrophage infiltration during diet induced-obesity in mice[J]. Brain Behav Immun, 2012, 26(6): 931–941. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.04.006 |

| [41] | Wasinski F, Bacurau RF, Moraes MR, et al. Exercise and caloric restriction alter the immune system of mice submitted to a high-fat diet[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2013, 2013: 395672. |

| [42] | Kawanishi N, Mizokami T, Yano H, et al. Exercise attenuates M1 macrophages and CD8+ T cells in the adipose tissue of obese mice[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2013, 45(9): 1684–1693. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828ff9c6 |

| [43] | Nickel T, Hanssen H, Emslander I, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of aerobic training in obesity[J]. Mediators Inflamm, 2011, 2011: 308965. |

2017, Vol. 43

2017, Vol. 43