扩展功能

文章信息

- 李夫, 王瑞白, 肖彤洋, 刘海灿, 蒋毅, 万康林

- Li Fu, Wang Ruibai, Xiao Tongyang, Liu Haican, Jiang Yi, Wan Kanglin

- 结核分枝杆菌对替比培南联用β-内酰胺酶抑制剂的敏感性分析

- In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to tebipenem alone or in combination with β -lactamase inhibitors

- 疾病监测, 2018, 33(3): 241-245

- Disease Surveillance, 2018, 33(3): 241-245

- 10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2018.03.017

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-10-01

随着世界范围内耐药结核病比例的不断上升,传统的一、二线抗结核药物已不能满足临床治疗的需求,寻找新的、更加有效的结核病治疗方案显得越来越紧迫。近年来,对于未曾用于结核病治疗的抗生素再利用策略逐渐受到重视[1]。由于结核分枝杆菌天然编码β-内酰胺酶(BlaC),长期以来,β-内酰胺类抗生素被认为不适合用于结核病的治疗。自2009年Hugonnet等[2]报道了美罗培南联用克拉维酸(CLA)对耐多药结核具有良好的抑菌效果以来,对于碳青霉烯类药物用于结核病治疗的前景越来越受到关注。替比培南(TBM)是近几年由日本研发的一种用于严重细菌感染的口服碳青霉烯类药物,最早用于儿童肺炎的治疗[3]。Hazra等[4]发现结核分枝杆菌BlaC对TBM的水解作用较弱,且其活性受到TBM的抑制。CLA是一种广谱的β-内酰胺酶抑制剂,通常与阿莫西林制成复合制剂,并已应用于临床多年。阿维巴坦(AVI)是一种新型的β-内酰胺酶抑制剂,能不可逆地抑制β-内酰胺酶的活性,与其他β-内酰胺酶抑制剂相比,AVI不会诱导β-内酰胺酶的产生且具有长效的抑酶作用[5-6]。然而,对于TBM及联用β-内酰胺酶抑制剂对结核分枝杆菌的体外抑菌效果的研究还十分缺乏。本研究通过对128株结核分枝杆菌的药物敏感性测试,初步探究TBM及联用β-内酰胺酶抑制剂对中国结核分枝杆菌临床分离株的体外抑菌效果,并分析菌株抗结核药物耐药表型和基因型与TBM药物耐药之间的关联性。

1 材料与方法 1.1 菌株来源128株结核分枝杆菌临床分离株选取自中国疾病预防控制中心(CDC)传染病预防控制所菌株库,来源于北京、福建、贵州、西藏、新疆、四川、安徽和重庆等省份,其中全敏感株50株,耐多药株65株,广泛耐药株13株。菌株抗结核药物耐药类型包括,一、二线药物(异烟肼、利福平、乙胺丁醇、链霉素、卷曲霉素、阿米卡星、卡那霉素和氧氟沙星)。128株菌中,北京家族96株,占75.0%(96/ 128);非北京家族32株(包括T、H、NEW、U、LAM和CAS,分别为16、3、7、4、1和1株),占25.0%(32/128)。

1.2 药敏试验采用96孔微孔板显色法,具体参照Hall等[7]的报道。实验所用CLA购自美国Sigma公司,TBM和AVI购自美国MCE公司。选取6株菌(3株敏感株,3株耐多药株)进行预实验,以摸索抑制剂的最适浓度。将TBM药物浓度倍比稀释为16~0.125 µg/ml,抑制剂分别设置5个固定浓度组(10、5、2.5、1.25和0.625 µg/ml),并同时设置不含药物的生长对照。37 ℃培养7 d后,向对照孔中加入70 µl显色剂(5%吐温80:Alamar blue显色剂为5:2),24 h后观察颜色变化。若对照孔由蓝色变为粉红色,说明细菌已生长,此时将显色剂加入含药物孔中,24 h后读取结果。最低抑菌浓度(minimum inhibitory concentration,MIC)为能阻止显色剂颜色发生变化的最低药物浓度,临界浓度参考美国临床和实验室标准协会(CLSI)发布的M24-A2文件中,碳青霉烯类药物对分枝杆菌的临界浓度,MIC ≤4 µg/ml判定为敏感。

1.3 数据分析Spoligotyping数据分析采用BioNumerics 5.0软件,并与数据库SpolDB 4.0比对确定菌株基因型。采用SAS 9.2软件对不同表型和基因型菌株的耐药情况进行χ2检验,P < 0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 TBM及抑制剂组合物的体外抑菌效果在对6株结核分枝杆菌的药敏实验中,加入CLA或AVI后,MIC均出现了明显的下降。TBM分别在含1.25 µg/ml的CLA和5 µg/ml的AVI的培养基中具有最高的抑菌活性,而随着抑制剂浓度的继续升高,MIC值不再降低(表 1)。因此,后续大量药敏实验中所采用的CLA和AVI的浓度分别固定为1.25 µg/ml和5 µg/ml。

| 抑制剂 | 浓度(pg/ml) | |||||

| 0 | 0.625 | 1.25 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | |

| 阿维巴坦 | 8~16 | 4~8 | 2~4 | < 1~4 | < 1~2 | < 1~2 |

| 克拉维酸 | 8~16 | < 1~2 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 | < 1 |

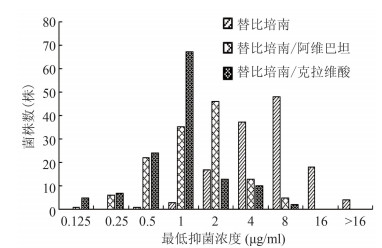

128株菌中,TBM的MIC值分布较广,多数菌株对其耐药,耐药率为54.7%(70/128),主要分布在8 µg/ml的药物浓度上。在加入β-内酰胺酶抑制剂后,其MIC值显著降低(4~8倍)。其中,TBM/CLA组合的抑菌效果最佳,MIC值主要分布在1 µg/ml和0.5 µg/ml,相应菌株数分别为67株(52.3%)和24株(18.8%);仅有2株菌耐药。TBM/AVI组合同样具有较好的抑菌效果,仅有5株耐药菌。TBM/AVI组合的MIC主要分布在1 µg/ml和2 µg/ml,见图 1。

|

| 图 1 128株结核分枝杆菌临床分离株的最低抑菌浓度分布 Figure 1 Distribution of MICs to 128 clinical M. tuberculosis isolates |

| |

不同耐药表型菌株中,抗结核药物敏感(DS)和耐多药/广泛耐药(M / XDR)菌株对TBM的MIC50分别为8 µg/ml和4 µg/ml,MIC90一致,均为16 µg/ml;对TBM/AVI的MIC50分别为2 µg/ml和1 µg/ml,MIC90一致,均为4 µg/ml;二者对TBM/CLA的MIC50一致,均为1 µg / ml,但前者MIC90(4 µg / ml)高于后者(2 µg/ml)。在不同基因型菌株中,北京基因型和非北京基因型菌株对TBM的MIC50分别为8 µg/ml和4 µg/ml,MIC90分别为16 µg/ml和8 µg/ml,前者均高于后者;对TBM / AVI的MIC50分别为2 µg / ml和1 µg/ml,MIC90分别为16 µg/ml和8 µg/ml,前者同样均高于后者;二者对TBM/CLA的MIC50一致,均为1 µg/ml,但前者MIC90(4 µg/ml)高于后者(2 µg/ml),见表 2。

| 特征分类 | 药物 | MIC范围(μg/ml) | MIC50(μg/ml) | MIC90(μg/ml) |

| 耐药类型 | ||||

| 敏感 | 替比培南 | 2~ > 16 | 8 | 16 |

| 替比培南/阿维巴坦 | 0.5~8 | 2 | 4 | |

| 替比培南/克拉维酸 | 0.25~8 | 1 | 4 | |

| 耐多药/广泛耐药 | 替比培南 | 0.5~ > 16 | 4 | 16 |

| 替比培南/阿维巴坦 | 0.125~8 | 1 | 4 | |

| 替比培南/克拉维酸 | 0.125~8 | 1 | 2 | |

| 基因型 | ||||

| 北京基因型 | 替比培南 | 1~ > 16 | 8 | 16 |

| 替比培南/阿维巴坦 | 0.25~8 | 2 | 4 | |

| 替比培南/克拉维酸 | 0.125~8 | 1 | 4 | |

| 非北京基因型 | 替比培南 | 0.5~16 | 4 | 8 |

| 替比培南/阿维巴坦 | 0.125~4 | 1 | 2 | |

| 替比培南/克拉维酸 | 0.125~2 | 1 | 2 |

DS菌株共50株,TBM耐药率为64.0%(32/50),M/XDR菌株共78株,耐药率为48.7%(38/78);对TBM/AVI耐药的DS菌株和M/XDR菌株分别为3株和2株,耐药率分别为6.0%(3/50)和2.6%(2/50);对TBM/CLA耐药的DS菌株和M/XDR菌株各1株,耐药率分别为2.0%(1/50)和1.3%(1/78)。经Pearson χ2检验分析可知,虽然DS菌株的耐药率均高于M/XDR菌株,但差异均无统计学意义(P >0.05),见表 3。

| 特征分类 | 菌株数 | 任一耐药 | 替比培南 | 替比培南/阿维巴坦 | 替比培南/克拉维酸 | |||||||

| 菌株数 | 耐药率(%) | 菌株数 | 耐药率(%) | 菌株数 | 耐药率(%) | 菌株数 | 耐药率(%) | |||||

| 耐药类型 | ||||||||||||

| 敏感 | 50 | 32 | 64.0 | 32 | 64.0 | 3 | 6.0 | 1 | 2.0 | |||

| 耐多药/广泛耐药 | 78 | 38 | 48.7 | 38 | 48.7 | 2 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.3 | |||

| χ2值 | 2.870 | 2.870 | 0.260 | - | ||||||||

| P值 | G.G9G | 0.090 | 0.609 | - | ||||||||

| 基因型 | ||||||||||||

| 北京型 | 96 | 58 | 60.4 | 58 | 60.4 | 5 | 5.2 | 2 | 2.1 | |||

| 非北京型 | 32 | 12 | 37.5 | 12 | 37.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |||

| χ2值 | 5.090 | 5.090 | 0.620 | - | ||||||||

| P值 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.429 | - | ||||||||

| 注:-表示菌株数量太少,无法进行统计 | ||||||||||||

北京型菌株共96株,对TBM耐药率为60.4%(58/96);非北京型菌株共32株,耐药率为37.5%(12/32),前者耐药率高于后者,且差异有统计学意义(χ2 = 5.090,P = 0.024)。TBM/AVI耐药菌株中,北京型菌株为5株,耐药率5.2%(5/96),并未检出非北京型菌株,统计学分析耐药率差异无统计学意义(P >0.05)。由于对TBM/CLA耐药的菌株数量太小,尚无法进行统计分析,见表 3。

3 讨论本研究选取128株源自中国多个省份的临床分离株,并对其进行了TBM及β-内酰胺酶抑制剂组合的药物敏感性研究。结果显示,多数菌株(54.7%)对TBM单药耐药,加入CLA后,菌株敏感性显著升高,MIC主要分布在0.5 µg/ml和1 µg/ml,仅有2株耐药菌株。TBM/AVI组合同样具有良好的抑菌活性,但MIC90稍高于TBM/CLA,与Horita等[8]报道的结果一致。而AVI活性相对较弱,可能是因为其本身具有较大的环状结构,从而影响了其抑制β-内酰胺酶的效力[5]。有研究表明,在空腹条件下,200 mg单剂量的TBM颗粒剂在血浆中的最大浓度能达到(9.4 ± 1.6)µg/ml [9],高于本结果中TBM和抑制剂组合物的MIC范围(0.125 ~ 8 µg/ml)。另外,临床上,阿莫西林/CLA的用量一般为3次/d,每次125 mg或250 mg,其中CLA在血液中的浓度峰值分别可达2.55 µg/ml或5.9 µg/ml [10]。本研究中所采用的CLA浓度为0.125 µg/ml,小于临床上所能达到的血药峰浓度。尽管TBM半衰期较短,但作为一种口服抗菌药物并表现出良好的抗结核效果,且具有较长的抗生素后效应(PAE)[11]。因此,TBM和抑制剂组合物用于结核病的临床治疗具有良好的应用前景,但其实际临床效果还有待进一步的研究。

有研究报道,相较于DS菌株,碳青霉烯类抗生素和抑制剂组合物对M/XDR菌株具有更低的MIC水平[8, 12-13]。本研究中,M/XDR菌株对3种药物组合的MIC水平整体低于DS菌株,可能是由于耐多药菌株存在多种突变,影响了其细胞壁的组成,从而导致其对碳青霉烯类抗生素更加敏感。目前,尚未见关于结核分枝杆菌抗结核药耐多药类型与TBM敏感性的相关研究报道。本文尝试分析二者之间的相关性,发现DS菌株与M/XDR菌株的耐药率差异均无统计学意义,这可能是由于多重耐药菌株是一类耐药菌株的统称,其中每个菌株药物靶点突变的情况可能不尽相同,因而可能导致统计分析的偏倚。因此,关于结核分枝杆菌抗结核药耐多药表型与TBM敏感性的相关性仍有待于更深入的研究。

由于耐多药北京基因型菌株多次引起爆发性流行,使得北京基因型菌株与耐药之间的关系成为研究的热点[14],但结果不尽相同。有研究报道,北京家族菌株作为优势菌株,具有更强的毒性和更容易产生耐药性[15-17]。也有文献报道,北京基因型菌株与非北京基因型菌株耐药率差异无统计学意义,如印度尼西亚、阿塞拜疆、中国浙江等地区[18-20]。本研究结果显示,北京家族菌株的TBM耐药率(60.4%)显著高于非北京家族菌株(37.5%),且MIC水平高于非北京型菌株。北京家族菌株比非北京家族可能对TBM更易耐药,支持北京家族更容易产生耐药性的观点。另外,由于非北京家族中未检出耐TBM/AVI和TBM/CLA的菌株,故无法对其进行统计分析,后续仍需更进一步的研究。

综上所述,TBM联用β-内酰胺酶抑制剂对我国结核分枝杆菌显示出良好的体外抑菌活性,但其实际临床应用效果还有待进一步的研究。北京基因型与TBM耐药呈现出相关性,未发现抗结核药物多重耐药表型与TBM耐药有相关性。

作者贡献:

李夫 ORCID:0000-0002-1814-6361

李夫:实验操作、数据整理及分析和文章撰写

王瑞白、肖彤洋、刘海灿、蒋毅:实验指导和实验操作

万康林:实验设计、实验指导和论文修改

| [1] |

D'Ambrosio L, Centis R, Sotgiu G, et al. New anti-tuberculosis drugs and regimens:2015 update[J]. ERJ Open Res, 2015, 1(1): 00010-2015. DOI:10.1183/23120541.00010-2015 |

| [2] |

Hugonnet JE, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, et al. Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Science, 2009, 323(5918): 1215-1218. DOI:10.1126/science.1167498 |

| [3] |

Sato N, Kijima K, Koresawa T, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of Tebipenem pivoxil(ME1211), a novel oral carbapenem antibiotic, in pediatric patients with otolaryngological infection or pneumonia[J]. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, 2008, 23(6): 434-446. DOI:10.2133/dmpk.23.434 |

| [4] |

Hazra S, Xu H, Blanchard JS. Tebipenem, a new carbapenem antibiotic, is a slow substrate that inhibits the β-lactamase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Biochemistry, 2014, 53(22): 3671-3678. DOI:10.1021/bi500339j |

| [5] |

Xu H, Hazra S, Blanchard JS. NXL104 irreversibly inhibits the β-lactamase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Biochemistry, 2012, 51(22): 4551-4557. DOI:10.1021/bi300508r |

| [6] |

Merdjan H, Rangaraju M, Tarral A. Safety and pharmacokinetics of single and multiple ascending doses of avibactam alone and in combination with ceftazidime in healthy male volunteers:results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies[J]. Clin Drug Investig, 2015, 35(5): 307-317. DOI:10.1007/s40261-015-0283-9 |

| [7] |

Hall L, Jude KP, Clark SL, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex for first and second line drugs by broth dilution in a microtiter plate format[J]. J Vis Exp, 2011(52): 3094. DOI:10.3791/3094 |

| [8] |

Horita Y, Maeda S, Kazumi Y, et al. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates to an oral carbapenem alone or in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2014, 58(11): 7010-7014. DOI:10.1128/aac.03539-14 |

| [9] |

Nakashima M, Morita J, Aizawa K. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tebipenem pivoxil fine granules, an oral carbapenem antibiotic, in healthy male volunteers[J]. Jpn J Chemother, 2009, 57: 90-94. |

| [10] |

White AR, Kaye C, Poupard J, et al. Augmentin(amoxicillin/clavulanate)in the treatment of community-acquired respiratory tract infection:a review of the continuing development of an innovative antimicrobial agent[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2004, 53(Suppl 1): i3-20. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkh050 |

| [11] |

Sugano T, Yoshida T, Yamada K, et al. Antimicrobial activity of tebipenem pivoxil against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, and its pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic profile in mice[J]. Jpn J Chemother, 2009, 57: 38-48. |

| [12] |

Forsman LD, Giske CG, Bruchfeld J, et al. Meropenem-clavulanic acid has high in vitro activity against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015, 59(6): 3630-3632. DOI:10.1128/aac.00171-15 |

| [13] |

Zhang D, Wang YF, Lu J, et al. In vitro activity of β-lactams in combination with β-lactamase inhibitors against multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015, 60(1): 393-399. DOI:10.1128/aac.01035-15 |

| [14] |

Anh DD, Borgdorff MW, Van LN, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype emerging in Vietnam[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2000, 6(3): 302-305. DOI:10.3201/eid0603.000312 |

| [15] |

Van Der Spuy GD, Kremer K, Ndabambi SL, et al. Changing Mycobacterium tuberculosis population highlights clade-specific pathogenic characteristics[J]. Tuberculosis, 2009, 89(2): 120-125. DOI:10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.003 |

| [16] |

Aguilar DL, Hanekom M, Mata D, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains with the Beijing genotype demonstrate variability in virulence associated with transmission[J]. Tuberculosis(Edinb), 2010, 90(5): 319-325. DOI:10.1016/j.tube.2010.08.004 |

| [17] |

Zhang HT, Li DF, Zhao LL, et al. Genome sequencing of 161Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from China identifies genes and intergenic regions associated with drug resistance[J]. Nat Genet, 2013, 45(10): 1255-1260. DOI:10.1038/ng.2735 |

| [18] |

车洋, 杨天池, 平国华, 等. 浙江省宁波地区耐多药结核分枝杆菌北京基因型的流行及与喹诺酮耐药关系的研究[J]. 疾病监测, 2017, 32(12): 962-965. Che Y, Yang TC, Ping GH, et al. Genotyping and quinolone resistance analysis of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis strains in Ningbo, China[J]. Dis Surveill, 2017, 32(12): 962-965. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2017.12.016 |

| [19] |

綦迎成, 刘洁, 鱼栓民, 等. 新疆结核分枝杆菌临床分离株Spoligotyping基因型的初步研究[J]. 疾病监测, 2010, 25(12): 951-954. Qi YC, Liu J, Yu SM, et al. Spoligotyping of clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Xinjiang[J]. Dis Surveill, 2010, 25(12): 951-954. DOI:10.3784/j.issn.1003-9961.2010.12.007 |

| [20] |

Van Crevel R, Nelwan RHH, De Lenne W, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains associated with febrile response to treatment[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2001, 7(5): 880-883. DOI:10.3201/eid0705.017518 |

2018, Vol. 33

2018, Vol. 33