2. 518036, 深圳市医诺智能科技发展有限公司

2. Shenzhen Yino Intelligence Technology Co. Ltd, Shenzhen 518036, China

放疗靶区和邻近的组织器官,特别是危及器官实际受到的照射剂量,即吸收剂量,是评估放疗疗效和不良反应或损伤的基础。由于直接计算的物理剂量(physical dose,PhD)受总剂量、分割计量、分次数等因素影响很大,难以进行比较,所以对预期疗效、不良反应和危及器官损伤的预测需要进行生物效应剂量(biological effective dose,BED)的换算。BED是指每次1.8~2.0 Gy,每周5次,总剂量60.0~70.0 Gy,即60.0~70.0 Gy/30~35次/6~7周的剂量分割模式下的剂量[1],一般以2.0 Gy计算,即常规2.0 Gy分次的等效剂量(equivalent dose in 2.0 Gy/f,EQD2)。这既是讨论肿瘤吸收剂量进行疗效判定的标准,也是靶区周围危及器官剂量控制的标准[2-4]。

在目前以适形和调强技术为主的精确放疗模式下,危及器官能够明确排除在靶区以外,所以每次的受照剂量较常规放疗明显减少[5-6]。常规分割模式下,危及器官每次的实际照射剂量明显低于2.0 Gy,因此危及器官特别是对分次剂量更为敏感器官的BED与PhD明显不同[7]。本研究结合L-Q(linear quadratic)模型[8],应用深圳市医诺智能科技发展有限公司的RTIS软件,在胸部肿瘤放疗患者中对这一问题进行探讨。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料选取2016年5月16日至2016年12月31日于我院应用美国VARIAN Eclipse Aria和美国PHILIPS Pinnacle计划系统完成治疗的30例胸部肿瘤患者,包括非小细胞肺癌、小细胞肺癌、食管癌、胸腺瘤和恶性淋巴瘤等。纳入标准:进行胸部靶区适形和调强放疗的患者。排除标准:胸部以外靶区照射患者。对上述治疗计划进行分析,治疗计划为95%计划靶体积(planning target volume,PTV)30~60 Gy/15~30次/3~6周。所有患者均在治疗前签署了知情同意书。

1.2 数据采集应用医诺RTIS V2.13软件,调取患者治疗计划,在常规计划评估界面显示脊髓和PTV的剂量分布情况。运行BED模块程序,匹配脊髓α/β值=3和PTV α/β值=10,显示脊髓和PTV的BED。两种情况均可同时显示剂量-体积直方图。从程序调取脊髓和PTV的最小、最大和平均剂量的PhD和BED数值进行统计分析。

1.3 统计学分析应用SPSS 19.0软件对数据进行统计学分析。脊髓和PTV的PhD和BED各均值符合正态分布且方差齐,分别进行均值比较和t检验,P<0.05表示差异有统计学意义。

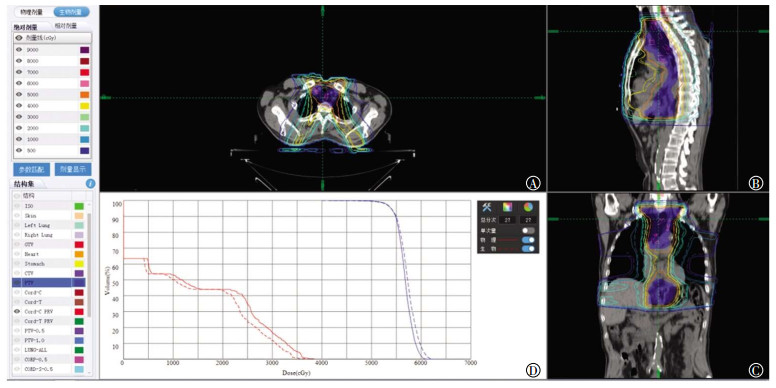

2 结果 2.1 治疗计划的评估评估显示1次剂量或总剂量下的PhD和BED等剂量曲线,从剂量-体积直方图可以看出,脊髓的BED曲线位于PhD曲线左侧,而PTV的BED曲线位于PhD曲线右侧(图 1中D、图 2中D)。

|

图 1 单次照射脊髓和PTV的PhD和BED(男性,54岁) Figure 1 The results of physicat dose and biological effective dose in cord and planning target volume for single radiation 图中, A:轴位剂量分布; B:矢状位剂量分布; C:冠状位剂量分布; D:体积-剂量直方图(红色为脊髓, 蓝色为PTV, 点线为BED, 实线为PhD)。GTV:大体肿瘤体积; CTV:临床靶体积; PTV:计划靶体积; PhD:物理剂量; BED:生物效应剂量。 |

|

图 2 30次照射脊髓和PTV的PhD与BED(男性,54岁) Figure 2 The results of physicat dose and biological effective dose in cord and planning target volume for 30 radiations 图中, 轴位剂量分布; B:矢状位剂量分布; C:冠状位剂量分布; D:体积-剂量直方图(红色为脊髓, 蓝色为PTV, 点线为BED, 实线为PhD)。GTV:大体肿瘤体积; CTV:临床靶体积; PTV:计划靶体积; PhD:物理剂量; BED:生物效应剂量。 |

由表 1可见,脊髓的PhD和BED的最小、最大、平均剂量的差异均有统计学意义(t=0.826、6.143、5.234,均P<0.05);而PTV的PhD和BED的最小、最大、平均剂量的差异均无统计学意义(t=6.953、-2.164、-1.193,均P>0.05)。但由于脊髓是典型的串行器官,因此,最小剂量、平均剂量的参考价值较小,临床主要应用最大剂量。

| 表1 30 例胸部肿瘤患者脊髓和PTV的PhD与EQD2比较(x±s) Table 1 The comparison of physical dose and biological effective dose in cord and planning target volume for 30 thoracic tumor patients(x±s) |

依据线性二次方程(L-Q模型)计算出2.0 Gy照射1次和30次时脊髓(α/β比值=3.0)在不同剂量曲线的PhD和BED。由表 2可见,随着剂量曲线下降,PhD和BED也随之降低,而且相同剂量曲线的BED较PhD更低。

| 表2 30例胸部肿瘤患者接受2.0 Gy 1次和30次照射时脊髓在不同剂量曲线下的PhD和BED Table 2 The data of physiacal dose and biological effective dose of cord in different dose curves with 2.0 Gy single and 30 radiations for 30 patients |

本研究应用的RTIS V2.13软件的治疗计划评估功能具有PhD显示和BED显示的双重模式,并且可以对照显示。在治疗计划评估中,可以选择单次治疗或全程治疗,软件以三维断面剂量曲线图和剂量-体积直方图形式显示PhD和BED(图 1、图 2)。

3 讨论放疗是利用放射线(主要是X射线)杀灭肿瘤细胞并治疗肿瘤。虽然近年来研究者认识到放疗与免疫的关系,并赋予放疗以全新概念[10],但是,对靶区剂量的控制和对周围组织特别是危及器官的最大限度防护,仍是放射物理学研究的主要问题[11]。虽然一直强调对于病变组织给予更高的剂量,但是在常规放疗中,射线不能充分避开周围正常组织和危及器官,因此受到正常组织特别是危及器官耐受性的限制,治疗剂量必须限制在一定水平[12]。也就是说,靶区附近危及器官的耐受量限制了靶区剂量的提高,因此不能实现由于提高肿瘤照射剂量而获得的疗效最大化。

近年来,临床放疗取得了突飞猛进的发展,以适形和调强技术为代表,现代放疗进入了以精确定位、精确计划、精确治疗为特色的时代。精确放疗的最大优势是靶区可以获得均匀的最大剂量的照射,同时靶区周围组织特别是危及器官受到最小剂量的照射[13-17]。在这种治疗模式的治疗计划下,危及器官的受照剂量一般位于等剂量曲线70%以下的剂量范围。也就是说,在常规分割模式下,危及器官每次实际的受照剂量往往低于1.4 Gy,显然,其生物效应明显降低,特别是对于脊髓等对分割剂量非常敏感的晚反应组织,其损伤程度明显降低。

上世纪20年代,国际辐射单位与测量委员会(ICRU)规范了辐射剂量单位,量化了辐射标准,放射物理、放射生物研究和临床治疗有了统一的剂量标准。PhD是指生物组织得到或吸收的剂量。根据国际原子能委员会第30号报告定义,BED是对生物体辐射反应程度的测量[18]。显然,PhD和BED是两个不同的概念,两者考察的侧重点完全不同。PhD是实际受到射线照射的量值,BED是受照剂量转化为常规分割后的量值。但是,两者又有密切联系,PhD越大,BED越大,生物效应越明显。然而,不同的组织或器官对这种增大的反应能力有很大差异。

1973年,Chadwick和Leenhouts[19]根据细胞存活曲线推导出L-Q模型,使不同时间、剂量、次数或不同分割方案的BED得以比较。同时,也可以通过BED对同一组织或危及器官在不同PhD下的生物效应进行评估[8]。

从放射生物学或放射损伤角度来说,脊髓几乎没有增殖能力,损伤后仅以修复代偿其正常功能,是典型的晚反应组织,对分次剂量的变化极为敏感,加大分次剂量时,损伤明显加重。相反,在常规分割模式下,随着PhD的降低,BED明显下降,损伤风险进一步减小。

颈部、胸部和上腹部肿瘤进行放疗时,脊髓均是需要控制受照剂量的危及器官。但是,使用PhD对分次剂量极为敏感的晚反应组织的生物效应进行评价显然不科学,需要换算为BED。在常规分割模式下,适形和调强治疗技术可以很好地防护邻近的组织器官,能够确保脊髓受到更低的照射剂量,这种低剂量带来更低的BED,使脊髓得到更好的保护[26]。另一方面,这种更高的脊髓BED耐受,可以使靶区的照射剂量得到提高,同时可以提高肿瘤的控制率。

临床放疗计划的审核需要考虑靶区剂量和危及器官受量,在常规分割模式下,靶区位于95%剂量曲线之内,因此PhD相当于BED,但是靶区以外的组织和危及器官因PhD的下降,会出现PhD与BED不一致。脊髓等晚反应组织对分次剂量更为敏感,因此会出现BED的进一步下降,也就是说脊髓等器官的耐受性提高。等剂量曲线下,实际BED与PhD并不一致,但这种差别在PhD图上看不出来。例如一个治疗计划,常规分割2.00 Gy/次,治疗次数为35,靶区PhD和BED约为70.00 Gy,如果脊髓剂量曲线为70%,则PhD为49.00 Gy,如果按照脊髓最大耐受剂量45.00 Gy进行评估,则计划不可行。但是,考虑脊髓实际以1.40 Gy/次的分割剂量受到照射,虽然PhD达到了49.00 Gy,但BED仅为43.05 Gy,显然在脊髓最大耐受剂量范围之内,则计划可行。

临床进行计划评估的常用软件,即治疗计划系统均是直接显示PhD,不能显示不同剂量曲线下当前靶区或危及器官的BED。因为一般临床治疗计划要求靶区位于95%剂量范围内,所以靶区本身PhD和BED差别不大,一般靶区的肿瘤组织α/β值较高(>10),对分次剂量并不敏感,因此在常规分割模式下,PhD与BED差别不大。但对于危及器官,特别是脊髓,随着PhD的下降,BED进一步降低,生物效应更趋于降低,因此对器官的保护效应更加明显。从肿瘤控制角度来说,这种确有把握的脊髓受量可以转化为靶区剂量的提高,从而提高肿瘤的控制率。在临床放疗计划中考虑到这种差别,并进行BED的评估显然可以使治疗计划更加科学、合理,对肿瘤的控制和脊髓损伤的防护均可达到最大化。

多年来,剂量-时间等放射生物学因素对临床BED研究具有明确的指导意义[28]。本研究应用RTIS V2.13软件对脊髓BED进行研究的结果与放射生物学理论值相符。在临床应用中,RTISV2.13软件系统对靶区和危及器官除了以直观的剂量曲线和剂量-体积直方图形式显示以外,也以数值列表形式显示体积、PhD和BED的最小剂量、最大剂量和平均剂量,以便于进一步细节评价。RTIS V2.13软件编程以线性二次方程(L-Q模型)公式为内核,同时考虑了优先级和治疗中断等对BED有影响的临床和放射生物学参数,α/β比值有常规预设,但也可以根据临床治疗自行设定,以进行个体化的评估。

总之,在常规分割治疗模式下应用适形和调强技术,应使用BED对脊髓的受照剂量进行控制和评估,从而提高肿瘤的治疗愈率。

利益冲突 本研究由署名作者按以下贡献声明独立开展,不涉及任何利益冲突。

作者贡献声明 刘卫东负责研究总体设计、方法的建立和论文的撰写;刘建平负责病例资料的收集、整理;郭猛负责医诺RTIS软件开发;杨海芳负责数据的整理;姜斌负责数据统计分析;徐春雨负责论文的校对。

| [1] | Jones B, Dale RG, Deehan C, et al. The role of biologically effective dose(BED) in clinical oncology[J]. Clin Oncol(R Coll Radiol), 2001, 13(2): 71–81. DOI:10.1053/clon.2001.9221 |

| [2] | Fowler JF. 21 years of biologically effective dose[J]. Br J Radiol, 2010, 83(991): 554–568. DOI:10.1259/bjr/31372149 |

| [3] | Mouttet-Audouard R, Lacornerie T, Tresch E, et al. What is the normal tissues morbidity following Helical Intensity Modulated Radiation Treatment for cervical cancer?[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2015, 115(3): 386–391. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.02.010 |

| [4] | Hopewell JW, Millar WT, Lindquist C, et al. Application of the concept of biologically effective dose (BED) to patients with Vestibular Schwannomas treated by radiosurgery[J]. J Radiosurg SBRT, 2013, 2(4): 257–271. |

| [5] | Su SF, Huang Y, Xiao WW, et al. Clinical and dosimetric characteristics of temporal lobe injury following intensity modulated radiotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2012, 104(3): 312–316. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2012.06.012 |

| [6] | Lee SH, Lee KC, Choi J, et al. Clinical applicability of biologically effectivedose calculation for spinal cord in fractionatedspine stereotactic body radiation therapy[J]. Radiol Oncol, 2015, 49(2): 185–191. DOI:10.1515/raon-2015-0008 |

| [7] | Wambersie A, Menzel HG, Gahbauer RA, et al. Biological weighting of absorbed dose in radiation therapy[J]. Radiat Prot Dosimetry, 2002, 99(1/4): 445–452. |

| [8] | Iwata H, Matsufuji N, Toshito T, et al. Compatibility of the repairable-conditionally repairable, multi-target and linear-quadratic models in converting hypofractionated radiation doses to single doses[J]. J Radiat Res, 2013, 54(2): 367–373. DOI:10.1093/jrr/rrs089 |

| [9] | Jin JY, Huang YM, Brown SL, et al. Radiation dose-fractionation effects in spinal cord:comparison of animal and human data[J]. J Radiat Oncol, 2015, 4(3): 225–233. DOI:10.1007/s13566-015-0212-9 |

| [10] | Deloch L, Derer A, Hartmann J, et al. Modern Radiotherapy Concepts and the Impact of Radiation on Immune Activation[J]. Front Oncol, 2016, 6: 141. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2016.00141 |

| [11] |

李玉, 徐慧军.

现代肿瘤放射物理学[M]. 北京: 中国原子能出版社, 2015: 526-530.

Li Y, Xu HJ. Modern radiophysicson tumor[M]. Beijing: China Atomic Energy Press, 2015: 526-530. |

| [12] | Gandhi AK, Sharma DN, Rath GK, et al. Early clinical outcomes and toxicity of intensity modulated versus conventional pelvic radiation therapy for locally advanced cervix carcinoma:a prospective randomized study[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2013, 87(3): 542–548. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.06.2059 |

| [13] | Co J, Mejia MB, Dizon JM. Evidence on effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiotherapy versus 2-dimensional radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Meta-analysis and a systematic review of the literature[J]. Head Neck, 2016, 38 Suppl 1: E2130S-2142. DOI: 10.1002/hed.23977. |

| [14] | Peng G, Wang T, Yang KY, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing outcomes and toxicities of intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2012, 104(3): 286–293. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2012.08.013 |

| [15] | Zhang MX, Li J, Shen GP, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy prolongs the survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma compared with conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy:A 10-year experience with a large cohort and long follow-up[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2015, 51(17): 2587–2595. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.006 |

| [16] | Zhou GQ, Yu XL, Chen M, et al. Radiation-induced temporal lobe injury for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy and conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e67488[2018-02-05]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3707870/pdf/pone.0067488.pdf. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067488. |

| [17] | Dolezel M, Odrazka K, Zouhar M, et al. Comparing morbidity and cancer control after 3D-conformal (70/74 Gy) and intensity modulated radiotherapy (78/82 Gy) for prostate cancer[J]. Strahlenther Onkol, 2015, 191(4): 338–346. DOI:10.1007/s00066-014-0806-y |

| [18] |

殷蔚伯, 余子豪, 徐国镇, 等.

肿瘤放射治疗学[M]. 4版.北京: 中国协和医科大学出版社, 2008: 276.

Yin WB, Yu ZH, Xu GZ, et al. Radiation oncology[M]. 4th ed. Beijing: China Union Medical University Press, 2008: 276. |

| [19] | Chadwick HK, Leenhouts HP. A molecular therapy of cell survival[J]. Physic Med Biol, 1973, 18: 78–87. DOI:10.1088/0031-9155/18/1/007 |

| [20] | Sanpaolo P, Barbieri V, Genovesi D. Biologically effective dose and definitive radiation treatment for localized prostate cancer:treatment gaps do affect the risk of biochemical failure[J]. Strahlenther Onkol, 2014, 190(8): 732–738. DOI:10.1007/s00066-014-0642-0 |

| [21] | Jin JY, Huang Y, Brown SL, et al. Radiation dose-fractionation effects in spinal cord:comparison of animal and human data[J]. J Radiat Oncol, 2015, 4(3): 225–233. DOI:10.1007/s13566-015-0212-9 |

| [22] | Barendsen GW. Dose fractionation, dose rate and iso-effect relationships for normal tissue responses[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1982, 8(11): 1981–1997. DOI:10.1016/0360-3016(82)90459-X |

| [23] | Maciejewski B, Taylor JM, Withers HR. Alpha/beta value and the importance of size of dose per fraction for late complications in the supraglottic larynx[J]. Radiother Oncol, 1986, 7(4): 323–326. DOI:10.1016/S0167-8140(86)80061-5 |

| [24] | Brenner DJ. Fractionation and late rectal toxicity[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2004, 60(4): 1013–1015. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.014 |

| [25] | Miralbell R, Robert SA, Zubizarreta E, et al. Dose-fraction sensitivity of prostate cancer deduced from radiotherapy outcomes of 5969 patients in seven international institutional datasets:α/β=1.4(0.9-2.2) Gy[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012, 82(1): e17–24. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.075 |

| [26] | Turesson I, Notter G. The influence of fraction size in radiotherapy on the late normal tissue reaction -Ⅰ:Comparison of the effects of daily and once-a-week fractionation on human skin[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 1984, 10(5): 593–598. DOI:10.1016/0360-3016(84)90289-X |

| [27] | Machtay M, Bae K, Movsas B, et al. Higher biologically effective dose of radiotherapy is associated with improved outcomes for locally advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma treated with chemoradiation:an analysis of the radiation therapy oncology group[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2012, 82(1): 425–434. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.004 |

| [28] | Xia B, Chen GY, Cai XW, et al. The effect of bioequivalent radiation dose on survival of patients with limited-stage small-cell lung cancer[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2011, 6: 50. DOI:10.1186/1748-717X-6-50 |

2018, Vol. 42

2018, Vol. 42