前列腺癌(prostate cancer, PCa)是一种具有致死和惰性表型的异质性疾病。根据美国癌症学会估算,2017年新发PCa病例约161 360例,约有26 730例将死于该疾病[1]。目前我国PCa发病率低于欧美国家,但近年随着人口老龄化及生活条件的改善,发病率有明显增加的趋势。另据报道,PCa患者在术后10年内复发的发生率高达27%~53%[2]。此时,对于病灶的精确定位和诊断就显得十分重要。

目前用于诊断PCa的PET显像剂主要有18F-FDG、11C-胆碱、18F-胆碱、68Ga-前列腺特异性膜抗原(68Ga-prostate-specific membrane antigen,68Ga-PSMA)等。18F-FDG作为葡萄糖类似物在多数肿瘤诊断中广泛应用,但因其在PCa细胞中利用率低、对PCa细胞的特异性差[3],因此18F-FDG用于诊断PCa的效果不够理想。胆碱是合成细胞膜的主要成分,由于胆碱激酶在肿瘤细胞中过度表达,导致放射性核素标记的胆碱在肿瘤中聚集。尽管11C-胆碱和18F-胆碱结构相似,但在物理半衰期和生理排泄模式中差异很大。11C-胆碱主要通过肝胆系统排泄,尿路排泄少,有利于PCa成像[4-6],但因半衰期短,只有20 min,使其在临床应用中受到极大的限制。18F-胆碱半衰期长(110 min),由尿道排出,导致其在膀胱中大量聚集,不利于PCa成像[6]。PSMA是一种Ⅱ型膜糖蛋白,在PCa细胞中过度表达,是检测、诊断和治疗PCa的理想靶点。68Ga-PSMA是由68Ga和PSMA组成的螯合物。最近的研究表明,68Ga-PSMA在局部分期方面优于常规显像剂(如18F-胆碱,11C-胆碱)[7-12],并且68Ga-PSMA PET/CT可以明显提高淋巴结转移的检测准确率[12]。

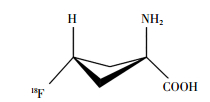

1979年Washburn等[13]合成了用于人体成像的放射性示踪剂1-氨基环丁烷-1-甲酸(1-aminocy-clobutane-1-[11C] carboxylic acid, 11C-ACBC)。1999年Shoup等[14]用氟原子取代氢原子的ACBC类似物,合成得到18F-氟环丁烷羧酸(18F-fluorocyclo-butane carboxylic acid, 18F-FACBC)。其化学名为反式-1-氨基-3-18F-氟环丁烷酸(anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocy-clobutane-1-carboxylic acid);分子式为C21H26N2O5;相对分子质量为132.12。18F-FACBC的化学结构见图 1。18F-FACBC与11C-ACBC具有相似的显像特点,但由于18F具有较长的半衰期且利于商品化,因此18F-FACBC逐渐成为人们研究的热点。后由英国Blue Earth Diagnostics公司开发18F-FACBC用于诊断PCa的PET显像剂,商品名为Axumin,并于2016年5月27日经美国食品药品监督管理局批准上市[15]。

|

图 1 18F-氟环丁烷羧酸的结构 Figure 1 Structure of 18F-fluorocyclo butane carboxylic acid |

18F-FACBC是合成的异亮氨酸类似物,被氨基酸转运蛋白吸收,导致在细胞内聚集。18F-FACBC经尿路排泄慢,且在膀胱聚集较少,有利于成像[16]。它主要分布在胰腺和肝脏中,骨髓分布较低[17]。18F-FACBC显像效果类似于11C-乙酸盐和18F-胆碱,18F-FACBC PET/CT对原发PCa诊断灵敏度高,但对良性前列腺增生和炎症等缺乏特异性[17-19]。Turkbey等[20]研究发现,18F-FACBC PET/CT诊断局部PCa的灵敏度和特异度分别为67%和66%。Kairemo等[17]对26例患者的18F-FACBC PET/CT图像进行分析,并对患者的前列腺特异性抗原(prostate specific antigen, PSA)浓度和PSA倍增时间进行比较,结果发现,阳性结果和阴性结果的PSA水平差异无统计学意义,且18F-FACBC PET诊断为阳性结果的患者显示出更短的倍增时间,表明18F-FACBC诊断为阳性结果的PCa侵袭性更强。18F-FACBC与11C-胆碱相比,无论患者的PSA水平高低,18F-FACBC都能检测到更多的复发或转移病灶[21]。

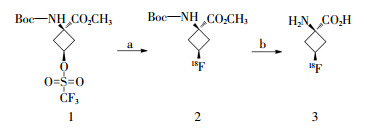

2 18F-FACBC的自动化合成18F-FACBC的放射合成路线见图 2[22]。以(1 s,3 s)-1-((叔丁氧基羰基)氨基)-3-((三氟甲基)磺酰氧基)环丁烷甲酸甲酯(图 2中1)为起始原料,经18F标记后得到(1 s,3 s)-1-((叔丁氧基羰基)氨基)-3-18F-氟环丁烷甲酸甲酯(图 2中2),然后经脱保护基和水解反应得到反式-1-氨基-3-18F-氟环丁烷酸,即18F-FACBC(图 2中3)。

|

图 2 18F-氟环丁烷羧酸的合成 Figure 2 Synthesis of 18F-fluorocyclo butane carboxylic acid |

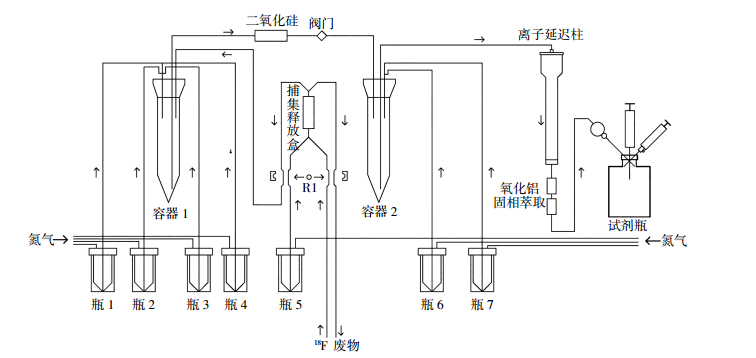

18F-FACBC自动化合成在化学过程控制单元中进行,见图 3。图中,瓶1:5 mg氨基聚醚和1 mL乙腈;瓶2:2 mL乙腈;瓶3:15 mg三氟甲磺酸酯前体1和1 mL乙腈;瓶4:10 mL二乙醚;瓶5:0.9 mg碳酸钾和0.6 mL水;瓶6:1.5 mL 4 mol/L盐酸;瓶7:15 mL无菌水。每个瓶配有氮气加压入口管线和特氟龙物料输出管线,可将瓶内的原料递送到化学过程控制单元内的容器1、容器2或捕集/释放盒中。容器1和2是发生化学反应的12 mL锥型瓶,其中包含来自相应v型小瓶的特氟龙管线,且可以独立加热。离子延迟柱组件包括离子延迟树脂、中性氧化铝和固相萃取柱。

|

图 3 自动化合成18F-氟环丁烷羧酸的流程图 Figure 3 Automated synthesis of 18F-fluorocyclo butane carboxylic acid |

首先,将H [18F] F的[18O] H2O溶液输送到捕集/释放盒中。立即将氨基聚醚乙腈溶液从瓶1加入到容器1中。捕集/释放盒释放K2CO3的水溶液加入到容器1制成K[18F]。将容器1加热至110 ℃ 7 min,蒸干溶剂,得到干燥的K[18F]。室温下冷却2.5 min,将瓶3的三氟甲磺酸酯前体1加入到容器1中,90℃加热10 min。加入[18F]F后,将乙醚从瓶4转移到容器1中,并打开阀门,将容器1中的内容物通过二氧化硅转移到容器2中,蒸去乙醚。将容器2加热至120℃,使中间体2(图 2中2)脱保护。将4 mol/L HCl从瓶6转移至容器2,并在120℃加热20 min。水合甲磺酸盐冷却1 min,然后用瓶7中的4 mL水稀释。将容器2中的水溶液转移到离子延迟柱中。将18F标记的产物通过离子延迟树脂、氧化铝和固相萃取柱串联纯化得到目标产物18F-FACBC。将产物18F-FACBC通过0.22 μm无菌过滤器注入含有0.7 mL 23.4%盐水的小试剂瓶,其预先装有两个注射器,以便取样进行质量控制。

3 18F-FACBC的质量控制18F-FACBC的质量控制主要包括无菌接种测试、致热原性、放射化学纯度、立体化学纯度、氨基聚醚含量、残留溶剂测定和pH测试[22]。无菌接种测试:使用Limulus Amebocyte裂解液一式两份,在20 min和60 min测试细胞内毒素。第2天在无菌层流罩中接种衰变样品(封闭无菌注射器),并将胰蛋白酶大豆肉汤培养基和流体巯基乙酸酯培养基培养皿孵育14 d,每天检查细菌生长。放射化学纯度由手性薄层色谱检测,展开剂为乙腈:甲醇:水20:5:5。立体化学纯度由二氧化硅薄层色谱检测,展开剂同上。将放射性核素标记产物的比移值与使用茚三酮染色(比移值0.3)显现的未标记产物的比移值进行比较,使用Chaly和Dahl[23]的方法评估产品中是否含有氨基聚醚。此外,残留溶剂的测定是使用火焰离子化检测器和DBWax柱的Varian Star 3400气相色谱仪(GC)系统进行分析。每批产品中有机溶剂的限值为二乙醚6.6 mg,乙醇4.9 mg,乙腈1.7 mg。

4 18F-FACBC的药理作用大量文献研究发现,18F-FACBC在PCa细胞中和异种移植裸鼠模型中摄取增加,其原因与PCa细胞中的丙氨酸-丝氨酸-半胱氨酸氨基酸转运蛋白和L-型氨基酸转运蛋白过度表达有关[21, 24-25]。由于癌细胞内氨基酸水平增加[26],且18F-FACBC被细胞吸收后不参与蛋白质的合成,导致18F-FACBC在癌细胞内聚集[15]。另一方面,在肾上皮细胞膜表达的一些激活素,能够重吸收近端小管中的氨基酸[27-28]。氨基酸转运蛋白在近端或远端小管的基底膜和肾集合管中表达,重吸收18F-FACBC导致其排入膀胱缓慢[29-30]。综合以上因素,18F-FACBC在肿瘤复发位点聚集浓度高且泌尿系统排泄缓慢,因此可以检测PCa复发病灶。

Oka等[16]对原位PCa移植模型大鼠体内的18F-FACBC生物分布进行研究发现,PCa淋巴结对18F-FACBC的摄取显著高于18F-FDG,可以准确区别PCa与淋巴结转移、淋巴结炎性和良性前列腺增生。Kanagawa等[31]通过18F-FACBC PET显像和生物分布分析,结果表明18F-FACBC在PCa转移灶的聚集明显高于淋巴结炎性病灶,证明其可用于鉴别诊断PCa和急性炎症。

5 18F-FACBC的临床研究Asano等[32]进行的18F-FACBC用于诊断PCa患者的Ⅰ期临床试验证实,PCa患者单次静脉注射18F-FACBC是安全的。注射后分析患者1~15、1~30、30~45、45~60 min和60~90 min的PET图像,结果发现,18F-FACBC在1~15 min快速分布到肿瘤组织,可持续30 min,在15 min浓度达到最大值[19]。当18F-FACBC注射剂量为93.8~287.8 MBq时可获得较好质量的PET图像[33]。Turkbey等[20]在PCa切除术和激素治疗前对21例PCa患者进行前瞻性研究,证实肿瘤组织摄取18F-FACBC比正常组织摄取更高。此外,Nanni等[34]也报道了18F-FACBC在人体内具有以下优点,中度异源骨髓活性和轻度肌肉活性,在唾液、淋巴和垂体组织中有中度摄取,在肠道中有轻中度活性,在肾脏中吸收较少,且肾脏排泄非常缓慢,在泌尿道和膀胱中无活性。因18F-FACBC在泌尿系统中分布较少,因此可以显著地降低由于泌尿道中示踪剂的存在而造成的泌尿道肿瘤复发检测的假阴性率[35]。由于18F-FACBC在大脑中摄取低且肾排泄慢,因此有利于脑和盆腔的成像。但是18F-FACBC在肝脏和胰腺中吸收较强,因此不利于这些器官的疾病检测。

Inoue等[36]对10例转移性PCa患者进行18F-FACBC Ⅱ期临床试验,测试其安全性,结果发现仅有2例患者有轻度不良反应,并且不治自愈。另外McConathy等[22]研究报道4例1级不良反应(味觉紊乱2例,轻度头痛2例),之后均自发消退。

18F-FACBC在临床研究过程中也发现存在假阳性或假阴性。在PCa、良性前列腺增生和前列腺内皮瘤中均存在18F-FACBC的摄取,从而导致假阳性的结果,此现象可通过联合应用18F-FACBC MRI和18F-FACBC PET/CT来避免。Ren等[37]联合应用18F-FACBC MRI和18F-FACBC PET/CT可提高PCa检测的灵敏度和特异度,其检测PCa的灵敏度为87%,特异度为66%。同时Ren等[37]总结报道了18F-FACBC PET/CT常见假阳性和假阴性的原因。当出现局部的强回声,并伴有CT、MRI和超声可见的解剖异常时,常见的假阳性原因包括骨样骨瘤、垂体腺瘤、前列腺增生等。常见的假阴性原因包括:根治性前列腺切除术、非根治性前列腺切除术等。

综上所述,18F-FACBC PET显像剂具有很好的体内分布、良好的药物代谢动力学参数、较长的半衰期以及易合成等优点,因此18F-FACBC具有广阔的应用前景。

利益冲突 本研究由署名作者按以下贡献声明独立开展,不涉及任何利益冲突。

作者贡献声明 高骏负责论文撰写;段玉清、于江、李祎亮负责论文指导和审校。

| [1] | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2017, 67(1): 7–30. DOI:10.3322/caac.21387 |

| [2] | Simsir A, Cal C, Mammadov R, et al. Biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy:is the disease or the surgeon to blame?[J]. Inter Braz J Urol, 2011, 37(3): 328–335. DOI:10.1590/S1677-55382011000300006 |

| [3] | Avril N, Dambha F, Murray I, et al. The clinical advances of fluo-rine-2-D-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography in urological cancers[J]. Int J Urol, 2010, 17(6): 501–511. DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02509.x |

| [4] | Lindenberg L, Choyke P, Dahut W. Prostate cancer imaging with novel PET tracers[J]. Curr Urol Rep, 2016, 17(3): 18. DOI:10.1007/s11934-016-0575-5 |

| [5] | Bauman G, Belhocine T, Kovacs M, et al. 18F-fluorocholine for prostate cancer imaging:a systematic review of the literature[J]. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis, 2012, 15(1): 45–55. DOI:10.1038/pcan.2011.35 |

| [6] | Krause BJ, Souvatzoglou M, Treiber U. Imaging of prostate cancer with PET/CT and radioactively labeled choline derivates[J]. Urol Oncol, 2013, 31(4): 427–435. DOI:10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.08.008 |

| [7] | Roethke MC, Kuru TH, Afshar-Oromieh A, et al. Hybrid positron emission tomography-magnetic resonance imaging with Gallium 68 prostate-specific membrane antigen tracer:a next step for imaging of recurrent prostate cancer-preliminary results[J]. Eur Urol, 2013, 64(5): 862–864. DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.003 |

| [8] | Afshar-Oromieh A, Zechmann CM, Malcher A, et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a (68) Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and (18) F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2014, 41(1): 11–20. DOI:10.1007/s00259-013-2525-5 |

| [9] | Afshar-Oromieh A, Avtzi E, Giesel FL, et al. The diagnostic value of PET/CT imaging with the (68) Ga-labelled PSMA ligand HBED-CC in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2015, 42(2): 197–209. DOI:10.1007/s00259-014-2949-6 |

| [10] | Eiber M, Maurer T, Souvatzoglou M, et al. Evaluation of hybrid 68Ga-PSMA ligand PET/CT in 248 patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy[J]. J Nucl Med, 2015, 56(5): 668–674. DOI:10.2967/jnumed.115.154153 |

| [11] | Eiber M, Weirich G, Holzapfel K, et al. 68Ga-PSMA HBED-CC PET/MRI in intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer improves the intraprostatic tumor localization compared to multiparametric Mr[J/OL]. J Nucl Med, 2016, 57(Suppl 2):28[2017-03-01]. http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/57/supplement_2/28.short. |

| [12] | Maurer T, Gschwend JE, Rauscher I, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of (68) Gallium-PSMA positron emission tomography compared to conventional imaging for lymph node staging of 130 consecutive patients with intermediate to high risk prostate cancer[J]. J Urol, 2016, 195(5): 1436–1443. DOI:10.1016/j.juro.2015.12.025 |

| [13] | Washburn LC, Sun TT, Byrd B, et al. 1-aminocyclobutane[11C]car-boxylic acid, a potential tumor-seeking agent[J]. J Nucl Med, 1979, 20(10): 1055–1061. |

| [14] | Shoup TM, Goodman MM. Synthesis of[F-18]-1-amino-3-fluorocy-clobutane-1-carboxylic acid (FACBC):A PET tracer for tumor delineation[J]. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm, 1999, 42(3): 215–225. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1344(199903)42:3<215:AID-JLCR180>3.0.CO;2-0 |

| [15] | Okudaira H, Shikano N, Nishii R, et al. Putative transport mechanism and intracellular fate of trans-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobu-tanecarboxylic acid in human prostate cancer[J]. J Nucl Med, 2011, 52(5): 822–829. DOI:10.2967/jnumed.110.086074 |

| [16] | Oka S, Hattori R, Kurosaki F, et al. A preliminary study of anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutyl-1-carboxylic acid for the detection of prostate cancer[J]. J Nucl Med, 2007, 48(1): 46–55. |

| [17] | Kairemo K, Rasulova N, Partanen K, et al. Preliminary clinical experience of trans-1-amino-3-(18) F-fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid (anti-(18) F-FACBC) PET/CT imaging in prostate cancer patients[J/OL]. Biomed Res Int, 2014:305182[2017-03-02]. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/305182/. DOI:10.1155/2014/305182. |

| [18] | Schuster DM, Taleghani PA, Nieh PT, et al. Characterization of primary prostate carcinoma by anti-1-amino-2-[(18) F]-fluorocyclobu-tane-1-carboxylic acid (anti-3-[(18) F] FACBC) uptake[J]. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2013, 3(1): 85–96. |

| [19] | Sörensen J, Owenius R, Lax M, et al. Regional distribution and kinetics of[18F]fluciclovine (anti-[18F]FACBC), a tracer of amino acid transport, in subjects with primary prostate cancer[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2013, 40(3): 394–402. DOI:10.1007/s00259-012-2291-9 |

| [20] | Turkbey B, Mena E, Shih J, et al. Localized prostate cancer detection with 18F FACBC PET/CT:comparison with Mr imaging and histopa-thologic analysis[J]. Radiology, 2014, 270(3): 849–856. DOI:10.1148/radiol.13130240 |

| [21] | Nanni C, Schiavina R, Boschi S, et al. Comparison of 18F-FACBC and 11C-choline PET/CT in patients with radically treated prostate cancer and biochemical relapse:preliminary results[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2013, 40 Suppl 1: S11–17. DOI:10.1007/s00259-013-2373-3 |

| [22] | McConathy J, Voll RJ, Yu W, et al. Improved synthesis of anti-[18F]FACBC:improved preparation of labeling precursor and automated radiosynthesis[J]. Appl Radiat Isot, 2003, 58(6): 657–666. DOI:10.1016/S0969-8043(03)00029-0 |

| [23] | Chaly T, Dahl JR. Thin layer chromatographic detection of kryptofix 2.2.2 in the routine synthesis of[18F]2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose[J]. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B, 1989, 16(4): 385–387. DOI:10.1016/0883-2897(89)90105-0 |

| [24] | Schuster DM, Votaw JR, Nieh PT, et al. Initial experience with the radiotracer anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid with PET/CT in prostate carcinoma[J]. J Nucl Med, 2007, 48(1): 56–63. DOI:10.1007/s00259-008-0993-9 |

| [25] | Schuster DM, Savir-Baruch B, Nieh PT, et al. Detection of recurrent prostate carcinoma with anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT and 111In-capromab pendetide SPECT/CT[J]. Radiology, 2011, 259(3): 852–861. DOI:10.1148/radiol.11102023 |

| [26] | Shuster JR, Lance RS, Troyer DA. Molecular preservation by extraction and fixation, mPREF:a method for small molecule biomarker analysis and histology on exactly the same tissue[J]. BMC Clin Pathol, 2011, 11(1): 14. DOI:10.1186/1472-6890-11-14 |

| [27] | Chillarón J, Estévez R, Mora C, et al. Obligatory amino acid exchange via systems bo, +-like and y+L-like. A tertiary active transport mechanism for renal reabsorption of cystine and dibasic amino acids[J]. J Biol Chem, 1996, 271(30): 17761–17770. DOI:10.1074/jbc.271.30.17761 |

| [28] | Romeo E, Dave MH, Bacic D, et al. Luminal kidney and intestine SLC6 amino acid transporters of B0AT-cluster and their tissue distribution in Mus musculus[J]. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2006, 290(2): F376–383. DOI:10.1152/ajprenal.00286.2005 |

| [29] | Bodoy S, Martín L, Zorzano A, et al. Identification of LAT4, a novel amino acid transporter with system L activity[J]. J Biol Chem, 2005, 280(12): 12002–12011. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M408638200 |

| [30] | Park SY, Kim JK, Kim IJ, et al. Reabsorption of neutral amino acids mediated by amino acid transporter LAT2 and TAT1 in the basolateral membrane of proximal tubule[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 2005, 28(4): 421–432. DOI:10.1007/BF02977671 |

| [31] | Kanagawa M, doi Y, Oka S, et al. Comparison of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid (anti-[18F]FACBC) accumulation in lymph node prostate cancer metastasis and lymphadenitis in rats[J]. Nucl Med Biol, 2014, 41(7): 545–551. DOI:10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2014.04.004 |

| [32] | Asano Y, Inoue Y, Ikeda Y, et al. Phase I clinical study of NMK36:a new PET tracer with the synthetic amino acid analogue anti-[18F]FACBC[J]. Ann Nucl Med, 2011, 25(6): 414–418. DOI:10.1007/s12149-011-0477-z |

| [33] | Inoue Y, Asano Y, Satoh T, et al. Phase Ⅱa clinical trial of trans-1-amino-3-(18) F-fluoro-cyclobutane carboxylic acid in metastatic prostate cancer[J]. Asia Ocean J Nucl Medi Biol, 2014, 2(2): 87–94. |

| [34] | Nanni C, Schiavina R, Rubello D, et al. The detection of disease relapse after radical treatment for prostate cancer:is anti-3-18F-FACBC PET/CT a promising option?[J]. Nucl Med Commun, 2013, 34(9): 831–833. DOI:10.1097/MNM.0b013e3283636eaf |

| [35] | Tolvanen T, Yli-Kerttula T, Ujula T, et al. Biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of[11C]choline:a comparison between rat and human data[J]. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2010, 37(5): 874–883. DOI:10.1007/s00259-009-1346-z |

| [36] | Inoue Y, Asano Y, Satoh T, et al. Phase Ⅱa clinical trial of trans-1-amino-3-18F-fluoro-cyclobutane carboxylic acid in metastatic prostate cancer[J]. Asia Ocean J Nucl Medi Biol, 2014, 2(2): 87–94. |

| [37] | Ren J, Yuan L, Wen G, et al. The value of anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluo-rocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT in the diagnosis of recur-rent prostate carcinoma:a meta-analysis[J]. Acta radiologica, 2015, 57(4): 487–493. DOI:10.1177/0284185115581541 |

2017, Vol. 41

2017, Vol. 41