2 虚拟地理环境教育部重点实验室(南京师范大学), 江苏 南京 210023;

3 江苏省地理信息资源开发与利用协同创新中心, 江苏 南京 210023)

末次冰期气候突变事件,如Dansgaard-Oeschger(DO)[1~2]和Heinrich (H)事件[3]一直是古气候研究的热点。在亚洲季风区,已有石笋记录将轨道-千年尺度季风变化拓展到64万年前[4~11]。这些记录对认识季风突变基本规律及其全球联系有着极为重要的学术价值和参考意义。近年来,随着高分辨率记录不断涌现,这些气候突变事件在内部结构、转型模式等方面表现出诸多区域差异[12~15]。特别是深海氧同位素3阶段(MIS3)晚期,短尺度气候突变尤为显著[16],有利于诊断其内部差异。如湖北三宝洞、黔西南大石包洞及雾露洞记录揭示了DO4~DO3细节过程[17],进一步优化了早期葫芦洞[4]时标和事件结构。而在最新发表的川东北石笋记录中[18],DO4和DO4.1的年龄比Zhao等[17]记录显著偏年轻,且DO4.1持续时间较短。这些差异是反映气候的区域性,还是由记录本身造成,需要进一步诊断。

同时,细节过程研究有利于认识季风突变动力学机制。早期,依据葫芦洞和冰芯记录时频特征与相对振幅方面相似性,Wang等[4]提出北大西洋温盐环流对亚洲季风的主控作用。在细节上,位于中国西南地区的小白龙记录显示[19],在DO12开始,季风抬升极为缓慢;中国中部宋家洞的DO4.1事件在幅度和持续时间上与中国东部记录一致,但有别于中国西南记录[20]。湖北青天洞高分辨率δ18O记录表明,较短时间尺度DO事件模式在高、低纬地区存在显著差异[21]。由此本文推断,亚洲季风除受到北高纬的主控外,还受到了低纬水热活动及南半球的影响[22]。因此,有必要从大区域、多记录角度对这些短尺度突变事件进行再考证,以此认识季风突变基本规律。

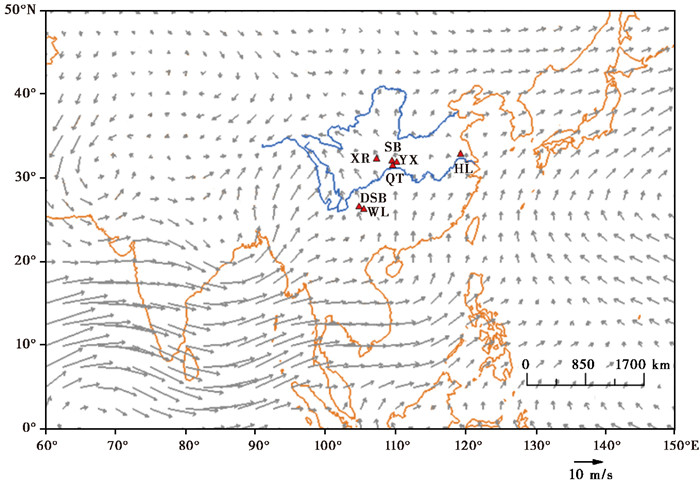

1 数据来源本文选取MIS3晚期7个洞穴8支石笋记录,区域范围跨北纬26°~33°,东经105°~120°之间,由南到北依次是黔西南雾露洞Wu3[23]和Wu32[17]、大石包洞DSB3[17]、长江中游青天洞QT15[21]、永兴洞YX51[24]、三宝洞SB46[17]、川东仙人洞XR025[18]以及南京葫芦洞MSD[4]。研究地点见图 1,洞穴石笋材料见表 1。

|

图 1 洞穴研究地点 研究地点包括:葫芦洞[4](HL:32°30′N,119°10′E),仙人洞[18](XR:32°24′N,107°10′E),三宝洞[17](SB:31°40′N,110°26′E),永兴洞[24](YX:31°35′N,111°14′E),青天洞[21](QT:31°20′N,110°22′E),大石包洞[17](DSB:26°05′N,105°03′E),雾露洞[17, 23](WL:26°03′N,105°05′E);灰色箭头表示研究区1981~2010年6~9月风向及风场强度 Fig. 1 Cave locations included in this study. Study sites include Hulu Cave[4](HL:32°30′N, 119°10′E), Xianren Cave[18](XR:32°24′N, 107°10′E), Sanbao Cave[17](SB:31°40′N, 110°26′E), Yongxing Cave[24](YX:31°35′N, 111°14′E), Qingtian Cave[21](QT:31°20′N, 110°22′E), Dashibao Cave[17](DSB:26°05′N, 105°03′E), and Wulu Cave[17, 23](WL: 26°03′N, 105°05′E). The gray arrows indicate wind directions and intensities between June and September, 1981~2010 |

| 表 1 研究材料概况 Table 1 Descriptions of cave sites and stalagmite records |

这些洞穴均处于亚洲季风区,平均年降水量范围为1000~2000mm,其中夏季6~9月降雨量占到全年降水量的50 %以上,年平均气温在7.4~15℃之间,最高温出现在夏季(6~9月)。据报道,这些洞穴内部湿度均接近100 % [4, 17~18, 21, 23-24]。

石笋记录遴选基于以下几点:1)发育时段位于MIS3晚期(约34~27kaB.P.期间);2)具有较高分辨率:除MSD和YX51外,其他分辨率均小于40a,其中QT15甚至达到了5a;3)包含部分或全部DO事件(DO5~DO3);4)年龄精度高,有3个或以上的测年控制点,且误差小于200a。因此,保证了短尺度气候突变事件具有较高的信噪比。

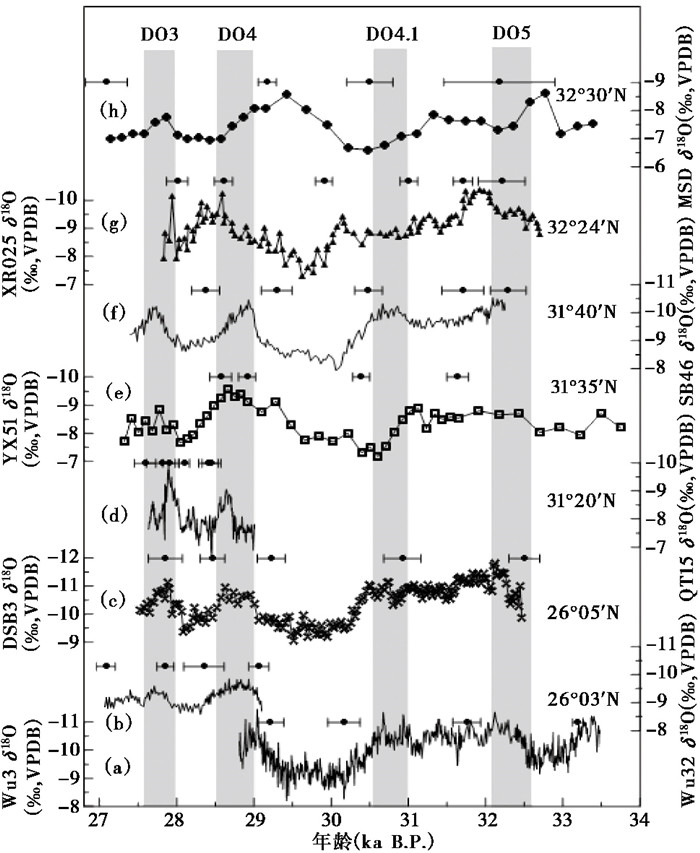

如图 2所示,8支石笋δ18O记录对比可见,在不同记录中,DO5~DO3事件有明显差异,主要体现在:1)事件的开始/结束时间不一致;2)同一事件在不同记录中持续时间长短不一;3)事件相对振幅存在差异;4)事件内部结构存在差异。据此,我们采用中值点的判断方式对DO5、DO4、DO4.1以及DO3这4个事件的开始/结束时间、振幅以及持续时间等进行分别统计,结果见表 1。其中,XR025和Wu3缺失DO3事件;QT15和Wu32缺失DO4.1事件;SB46、QT15和Wu32缺失DO5事件,其余石笋记录均完整覆盖DO5~DO3事件。

|

图 2 区域石笋δ18O记录对比 由南到北依次是:(a)雾露洞Wu32δ18O[23],(b)Wu3δ18O[17],(c)大石包洞DSB3δ18O[17],(d)青天洞QT15δ18O[21],(e)永兴洞YX51δ18O[24],(f)三宝洞SB46δ18O[17],(g)仙人洞XR025δ18O[18],(h)葫芦洞MSD δ18O[4]灰色阴影部分表示DO3、DO4、DO4.1和DO5事件;各记录测年点及其测年误差见图 Fig. 2 Regional correlation of δ18O records from different cave records. From south to north: (a)Wu32 δ18O[23], (b)Wu3 δ18O[17], (c)DSB3 δ18O[17], (d)QT15 δ18O[21], (e)YX51 δ18O[24], (f)SB46 δ18O[17], (g)XR025 δ18O[18], (h)MSD δ18O[4]. Gray bars illustrate each DO event, dating points and errors are indicated at the top of each record |

统计发现(图 2和表 1),DO3、DO4和DO5事件在不同记录中幅度差异较大,变化范围分别为0.8 ‰ ~1.7 ‰、0.9 ‰ ~1.7 ‰和0.6 ‰ ~1.4 ‰。DO4.1事件幅度差异较小,约为0.5 ‰ ~0.7 ‰;DO4和DO5事件在不同记录中持续时间差异较大,为230~1080a和310~1290a;DO3和DO4.1事件持续时间差异较小,为170~580a和90~530a。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 DO5~DO3事件区域特征早期研究发现,气候突变事件的振幅自低纬向高纬呈逐步增大[25~26]。图 2对比结果显示,在石笋记录中,MIS3晚期短尺度季风突变事件幅度没有显示出由南到北逐渐增大趋势。在不同石笋记录中,每个DO事件的振幅差最大可达0.9 ‰,持续时间差最大达到900a。

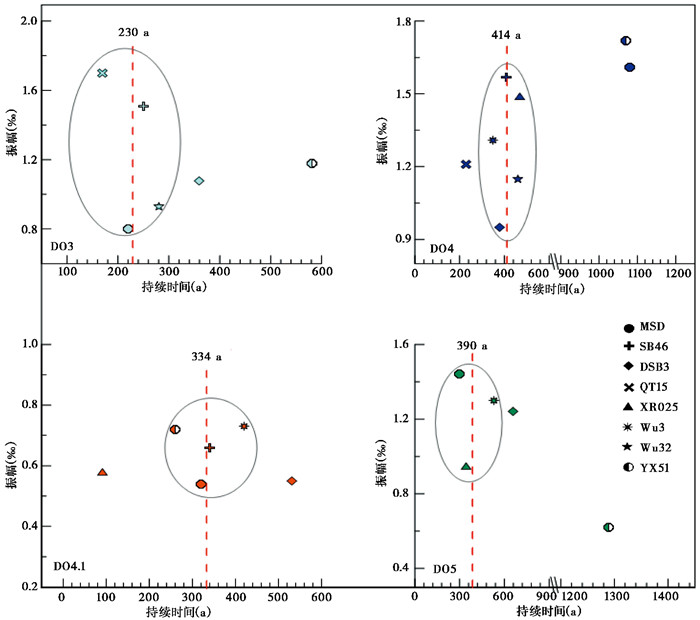

统计分析发现(图 3),DO5、DO4、DO4.1以及DO3这4个事件的振幅和持续时间并无直接的关联性,说明这二者没有相互影响。但就单个事件持续时间来看,上述4个小图均有一个共同特征,即除个别离散点外,其他半数以上的点都相对集中分布在一个范围内,比较接近于某一个数值。据此,我们用能反映数据离散程度的标准差,分别对DO5、DO4、DO4.1和DO3事件的持续时间进行了计算。结果发现:包含了DO3事件的6支石笋样本总的标准差较大,为134,而只选择QT15、SB46、WL32和MSD4这4支石笋,占总样本数67 % (半数以上,具有统计意义),且持续时间比较接近的圈内样本数进行计算,其标准差仅有40,这是总样本量半数以上组合的最小标准差值。由此说明,这4支石笋所记录的DO3事件更能反映出事件本身真实持续时间的值。然后再对这4支更接近真实值石笋的持续时间进行平均,得出持续时间约为230 a,即表示DO3事件的持续时间最有可能接近于230 a(图 3中垂直虚线所在位置)。用同样的方法对DO4、DO4.1和DO5分别进行计算评估,结果显示,DO4事件中,占总样本数63 %的5个圈内样本数,最小标准差为45,即DO4事件的持续时间应该比较接近410 a;DO4.1事件中,占总样本数67 %的4个圈内样本数,最小标准差为56,故DO4.1事件的持续时间应该接近于330a左右;同样,DO5事件占总样本数60 %的3个圈内样本数,最小标准差是100,所以DO5事件的持续时间应该更接近于390a左右。所以,虽然这8支地理位置相距较远且洞穴环境差异较大的石笋,所记录的MIS3晚期较短时间尺度的气候突变事件其振幅和持续时间等均有差异性,但在差异性中却能够找到一定的共性。

|

图 3 DO事件持续时间及振幅诊断 灰色线圈范围由各事件幅度、持续时间变化最小方差决定,垂直虚线及数值指示圈内数值平均值 Fig. 3 Evaluation of the amplitude and duration of each DO event. Gray circles are drawn based on minimum-variance of δ18O changes in each DO event, in which vertical dotted lines and numbers show averaged values constrained by gray circles |

一般而言,石笋是由大气降水渗入土壤,再溶蚀基岩滴入洞内,形成次生碳酸盐柱状体,其在平衡状态下的形成机理为:水汽蒸发-输送-降水、渗流水与土壤及基岩进行交换、滴水沉积结晶[27~28]。水汽在运移过程中受到了地理位置、气候及下垫面等因素影响,会产生一系列同位素分馏过程,例如海陆效应、雨量效应、纬度效应等,从而使洞穴沉积中的δ18O与水汽源δ18O值产生一定的差异[29~31]。但研究表明[32],上述的“环境效应”在较短时间尺度上会对石笋δ18O值产生一定影响,对长时间尺度大气降水δ18O值的变化影响权重基本恒定。所以一般认为,石笋δ18O继承了大气雨水的同位素信号[33]。基于大气水分运移及氧同位素主控因素的差异,不同区域洞穴石笋的氧同位素值指代的气候意义不会完全相同。就亚洲季风系统而言,东亚季风与印度季风是其重要组成部分[34],其虽有复杂性,但对于特定洞穴地点而言,纬度、海拔及上覆基岩状态是恒定不变的,变化的只是水汽源、降水量和气温[35~36]。所以众多研究表明,亚洲季风区石笋氧同位素主要反映了与夏季风强度相关的大气降水δ18O值组成变化,即夏季风越强,δ18O越偏负,反之则越偏正[6, 10, 37]。罗维均等[38]研究发现,虽然洞穴顶板盖层的厚度、植被覆盖状况、洞穴内空气流通及相对湿度等会对大气降水-石笋氧同位素信号产生干扰,但总体上石笋氧同位素组成能直接反映大气降水δ18O及变化情况,即氧同位素信号在土壤带中的传递过程不会导致同位素信号的失真,石笋记录的同位素信号与大气降水水汽来源(即大气降水δ18O特征)的区域特征有关;同样,Hesterberg和Siegenthaler[39]观测发现,土壤CO2的δ18O值,无论年内还是年际变化均与土壤水的δ18O值变化一致,即二者之间的氧同位素交换是平衡的;其他学者也得出相似的结论[40]。据此,如图 3所示,在DO5、DO4、DO4.1和DO3事件持续时间统计中,都有≥60 %的样本数相对集中于一个最有可能代表事件可靠持续时间的数值。各个石笋间的“相似性特征”暗示尽管受到局地环境改造,但气候真实的信号可被石笋同位素记录保留或继承。

但由于上述洞穴南北跨7个纬度,东西跨15个经度,空间分布范围较广。受水汽来源、洞穴微环境、渗水通道及过程、生长动力等影响,同一事件在不同记录中的差异性可能反映同一气候信号受到局地环境的改造[41~43]。

Fairchild等[42]从大气、植被/土壤、岩溶含水层、洞穴堆积物晶体生长和次生蚀变等5个方面分析了影响洞穴地球化学的因素,认为在其影响下,气候信号的传递会逐步减弱,导致古气候记录信号的解译偏差;同样,Lachniet[43]通过分析大气、土壤、表层岩溶和洞穴方解石中对δ18O的多重控制作用,认为只有明确氧稳定同位素分馏的过程,才能深入了解现代气候与石笋δ18O之间的真实关系,更好的追踪过去气候和环境的变化[44~45]。就特定渗水通道或石笋而言,渗流水的滞留时间长短(即库效应)往往通过混合过程削弱气候事件的幅度[42]。研究表明,盖板通透性强,植被茂盛,洞穴滴水的主要来源是快速的优先流,反之则以基质流为主要运移方式[46]。“库效应”还可在数年内削弱岩溶水的季节性振幅,使得石笋生长母液的同位素组成季节变化远小于同期雨水同位素变化,变化幅度减小的程度取决于与水流机制相关的混合过程的效率和频率[47]。也就是说,上述洞穴石笋的δ18O信号差异可能反映沉积过程或同位素传递效应的复杂性(如图 2和3)。此外,样品发育的连续性、采样分辨率、测年精度和时标模式等也会影响具体DO事件的振幅。这些因素往往也是导致其持续时间差异的关键因素。因此,对石笋记录的古气候信号解译,需要建立在当地区域水文和气候学研究的基础上[45, 47~52]。

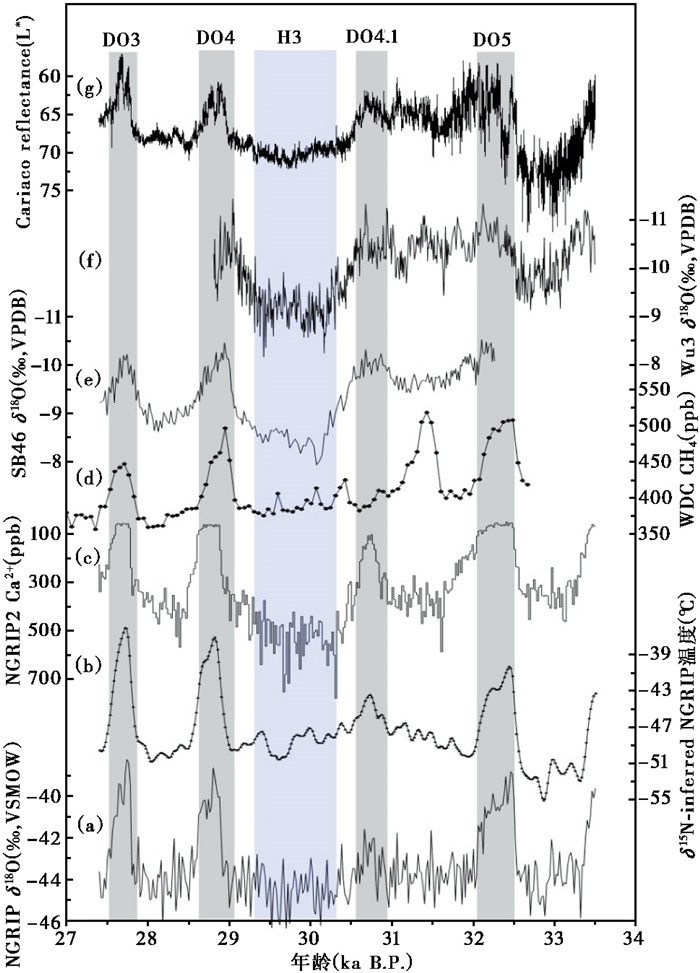

2.2 MIS3晚期季风突变事件与高、低纬联系如图 3所示,SB46和Wu3记录的DO5~DO3事件均位于灰色圈内,即其幅度和持续时间均落于最小方差范围内,可以代表该时段亚洲季风响应模式。与高、低纬记录对比显示(图 4),除了大气甲烷DO4.1事件(图 4d)偏老[53],其他DO事件发生的时间几乎一致。由此说明,在MIS3晚期,不同气候子系统的短尺度DO事件时频特征具有一致变化。

|

图 4 MIS3晚期DO事件高、低纬记录对比 (a)NGRIP冰芯δ18O[54];(b)NGRIP冰芯δ15N计算的温度[55];(c)NGRIP冰芯Ca2+浓度[54];(d)南极WDC冰芯CH4[56];(e)三宝洞SB46δ18O[17];(f)雾露洞Wu3δ18O[23];(g)Cariaco海盆岩芯反射率[56]灰色阴影分别表示DO5~DO3事件和H3事件 Fig. 4 egional correlation of different records during late MIS3. (a)NGRIP δ18O record[54], (b)δ15N-inferred NGRIP temperature record[55], (c)NGRIP Ca2+ record[54], (d)WDC methane record from Antarctic ice core[56], (e)SB46 δ18O record[17], (f)Wu3 δ18O record[23] and (g) the reflectance record from Cariaco Basin[56]. Gray bars show DO5~DO3 and H3 events |

在细节上,石笋记录[17, 23](图 4e和4f)与高北纬冰芯δ18O(图 4a)[54]、δ15N(图 4b)[55]表征的温度存在如下差异:1)在DO5~DO3的事件形态上,石笋所记录的亚洲季风突变事件在达到最强后,便会保持在这一稳定状态,在峰形上表现为矩形状的“方波形”,这和极地温度在DO峰值期表现出的逐步衰减过程不同;2)H3期间,极地气温基本维持较低水平(图 4a和4b)。而在H3晚期,亚洲季风逐步增强;3)在DO5冷阶(32~31kaB.P.),相对于DO5和DO4.1,季风强度几乎无衰减。而极地气温(图 4a和4b)和大气CH4浓度(图 4d)则下降显著。据研究,格陵兰冰芯的粉尘来源主要是亚洲内陆荒漠区[57~59],经强冬季风输送到格陵兰地区。所以,一般认为格陵兰冰芯的粉尘浓度在很大程度上可以指示亚洲冬季风强度[60],即格陵兰冰芯Ca2+离子浓度越大则冬季风越强。在DO5冷阶,Ca2+浓度增加并不显著(图 4c),反映冬季风较弱,侧面支持了“DO5冷阶期间稍强夏季风现象”。在H3期间,Ca2+离子浓度显著增大,显示冬季风增强;同期,石笋δ18O正偏,夏季风减弱。特别是在H3晚期,冰芯Ca2+浓度逐渐减小,石笋δ18O呈现负偏(图 4e和4f),说明亚洲冬夏季风呈反相位变化。

一般来说,大气CH4主要反映低纬湿地范围和CH4产率变化[61],与低纬季风的水汽循环变化紧密相关。然而,在DO5冷阶和H3期间,CH4记录(图 4d)与石笋及Ca2+浓度(图 4c)存在显著区别,即大气CH4浓度一直保持较低水平。有研究认为,在冷期,随着热力和水文中心南移进入南半球,北半球CH4产率降低[62]。如果这种关系成立,DO5~DO3期间季风与甲烷关系侧面支持北半球是大气CH4主要来源。另外的可能是,在H3晚期CH4记录分辨率较低,难以识别出夏季风增强现象。在热带大西洋,Cariaco海盆反照率(L*)指示的贸易风强度变化与亚洲夏季风变化一致(图 4g)[56]。在细节上,DO5冷阶和H3晚期贸易风强度与石笋记录耦合。

上述对比显示,石笋记录与高、低纬过程均存在相似特征,可能指示季风变化同时受到高、低纬影响。其中,千年尺度气候突变事件的开始及结束,即季风突变主要受到高北纬主控;而在事件内部则可能受到了中、低纬水热条件的影响。这种混合性特征说明,低纬季风与高北纬气候有着截然不同的驱动力,而低纬水热活动对亚洲夏季风突变气候信号的塑造及演化具有重要意义。

3 结论本文选择发育于MIS3晚期(34~27kaB.P.)亚洲季风区8个高分辨率石笋记录,空间范围跨北纬26°~33°之间,东经105°~120°。经对比发现,短尺度季风突变事件(DO5~DO3)时空差异显著:1)开始/结束时间不同;2)不同记录中,事件振幅偏差达0.7 ‰;3)事件持续时间相差约400a;4)同一事件在不同记录中内部结构不一致。其时空差异可能受到洞穴微环境、渗水通道及过程、生长动力、分辨率和测年精度等众多复杂因素的综合影响。同时,统计分析发现,这些短尺度DO事件持续时间集中分布于一定范围(DO5~DO3持续时间约为390a、330a、410a及230a)。这种“相似性特征”暗示尽管受到局地环境改造,但气候的真实信号并未被完全掩盖,可能被石笋同位素记录保留或继承。

高、低纬不同地质记录也存在显著差异:在事件振幅上,亚洲季风区石笋δ18O所记录的DO5~DO3事件的相对振幅较小,和北半球冰芯温度记录不同;在事件形态上,DO极盛期季风强度可维持长期稳定,同位素曲线表现为“方波形”,而极地温度则逐步衰减。在H3内部,尽管与低纬过程相关的大气CH4保持稳定,但亚洲夏季风逐步抬升。相比之下,北极气温长期维持在极地水平上,说明高、低纬气候在突变事件内部解耦。对比显示,冰芯Ca2+离子浓度示踪的亚洲冬季风在H事件内部逐步衰减,表明该期亚洲冬、夏季风可能呈反相位。在细节上,季风突变事件模式与贸易风强度变化类似。这些内部细节特征反映亚洲季风区石笋记录具有显著的“低纬特色”。因此,无论高纬气候信号是否是亚洲季风突变的“开关”,低纬过程确实是季风突变不可或缺的“塑造者”。在机制模拟研究中,低纬水热贡献需引起重视。

致谢: 感谢审稿专家及编辑部杨美芳老师给予的建设性修改意见,在此一并感谢!

| [1] |

Johnsen S J, Clausen H B, Dansgaard W, et al. Irregular glacial interstadials recorded in a new Greenland ice core[J]. Nature, 1992, 359(6393): 311-313. DOI:10.1038/359311a0 |

| [2] |

Dansgaard W, Johnsen S J, Clausen H B, et al. Evidence for general instability of past climate from a 250-kyr ice-core record[J]. Nature, 1993, 364(6434): 218-220. DOI:10.1038/364218a0 |

| [3] |

Heinrich H. Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130, 000 years[J]. Quaternary Research, 1988, 29(2): 142-152. |

| [4] |

Wang Y J, Cheng H, Edwards R L, et al. A high-resolution absolute-dated Late Pleistocene monsoon record from Hulu Cave, China[J]. Science, 2001, 294(5550): 2345-2348. DOI:10.1126/science.1064618 |

| [5] |

Wang Y J, Cheng H, Edwards R L, et al. The Holocene Asian monsoon:Links to solar changes and North Atlantic climate[J]. Science, 2005, 308(5723): 854-857. DOI:10.1126/science.1106296 |

| [6] |

Wang Y J, Cheng H, Edwards R L, et al. Millennial-and orbital-scale changes in the East Asian monsoon over the past 224, 000 years[J]. Nature, 2008, 451(7182): 1090-1093. DOI:10.1038/nature06692 |

| [7] |

Yuan D X, Cheng H, Edwards R L, et al. Timing, duration, and transitions of the last interglacial Asian monsoon[J]. Science, 2004, 304(5670): 575-578. DOI:10.1126/science.1091220 |

| [8] |

Zhang P Z, Cheng H, Edwards R L, et al. A test of climate, sun, and culture relationships from an 1810-year Chinese cave record[J]. Science, 2008, 322(5903): 940-942. DOI:10.1126/science.1163965 |

| [9] |

Cai Y J, Fung I Y, Edwards R L, et al. Variability of stalagmite-inferred Indian monsoon precipitation over the past 252, 000 y[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(10): 2954-2959. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424035112 |

| [10] |

Cheng H, Edwards R L, Sinha A, et al. The Asian monsoon over the past 640, 000 years and ice age terminations[J]. Nature, 2016, 534(7609): 640-646. DOI:10.1038/nature18591 |

| [11] |

赵侃, 孔兴功, 程海, 等. MIS3晚期东亚季风强度和DO事件年龄[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(1): 177-183. Zhao Kan, Kong Xinggong, Cheng Hai, et al. Intensity and timing of D-O events of East Asian monsoon during the late episode of MIS3[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(1): 177-183. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2008.01.020 |

| [12] |

王晓艳, 何尧启, 姜修洋. CIS 24事件的精确定年及亚旋回特征:以黔北三星洞石笋为例[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(6): 1418-1424. Wang Xiaoyan, He Yaoqi, Jiang Xiuyang. Precise dating of the Chinese-Interstadial 24 event and its sub-cycles inferred from a high resolution stalagmite δ18O record in northern Guizhou Province[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(6): 1418-1424. |

| [13] |

何尧启, 姜修洋. 黔北洞穴石笋记录的GIS-8事件亚旋回特征[J]. 第四纪研究, 2012, 32(3): 561-562. He Yaoqi, Jiang Xiuyang. Sub-Greenland-Interstadial 8 Event of Asian monsoon from a stalagmite record in northern Guizhou Province[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2012, 32(3): 561-562. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2012.03.23 |

| [14] |

刘殿兵, 汪永进, 陈仕涛, 等. 东亚季风MIS3早期DO事件的亚旋回及全球意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(1): 169-176. Liu Dianbing, Wang Yongjin, Chen Shitao, et al. Sub-Dansgaard-Oeschger events of East Asian monsoon and their global significance[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(1): 169-176. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2008.01.019 |

| [15] |

崔梦月, 洪晖, 孙晓双, 等. 福建仙云洞石笋记录的新仙女木突变事件结束时的缓变特征[J]. 第四纪研究, 2018, 38(3): 711-719. Cui Mengyue, Hong Hui, Sun Xiaoshuang, et al. The gradual change characteristics at the end of the Younger Dryas event inferred from a speleothem record from Xianyun cave, Fujian Province[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2018, 38(3): 711-719. |

| [16] |

Hinnov L A, Schulz M, Yiou P. Interhemispheric space-time attributes of the Dansgaard-Oeschger oscillations between 100 and 0 ka[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2002, 21(10): 1213-1218. DOI:10.1016/S0277-3791(01)00140-8 |

| [17] |

Zhao K, Wang Y J, Edwards R L, et al. High-resolution stalagmite δ18O records of Asian monsoon changes in Central and Southern China spanning the MIS3/2 transition[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2010, 298(1-2): 191-198. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.07.041 |

| [18] |

陈琼, 刘淑华, 米小建, 等. 川东北石笋记录的GIS 4-5夏季风气候变化及与高纬气候的联系[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(6): 1264-1269. Chen Qiong, Liu Shuhua, Mi Xiaojian, et al. Speleothem-derived Asian summer monsoon variations during Greenland Interstadials 4 to 5 in NE Sichuan, Central China and teleconnections with high latitude climates[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2014, 34(6): 1264-1269. |

| [19] |

Cai Y J, An Z S, Cheng H, et al. High-resolution absolute-dated Indian Monsoon record between 53 and 36 ka from Xiaobailong Cave, Southwestern China[J]. Geology, 2006, 34(8): 621-624. DOI:10.1130/G22567.1 |

| [20] |

Zhou H Y, Zhao J X, Feng Y X, et al. Heinrich event 4 and Dansgaard/Oeschger events 5-10 recorded by high-resolution speleothem oxygen isotope data from Central China[J]. Quaternary Research, 2014, 82(2): 394-404. |

| [21] |

王权, 汪永进, 刘殿兵, 等. DO3事件的湖北神农架高分辨率年纹层石笋记录[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(1): 108-116. Wang Quan, Wang Yongjin, Liu Dianbing, et al. The DO3 event in Asian monsoon climates evidenced by an annually laminated stalagmite from Qingtian Cave, Mt. Shennongjia[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(1): 108-116. |

| [22] |

孙喜利, 杨勋林, 史志超, 等. 石笋记录的西南地区MIS4阶段夏季风的演化[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(6): 1370-1380. Sun Xili, Yang Xunlin, Shi Zhichao, et al. The evolution of summer monsoon in Southwest China during MIS4 as revealed by stalagmite δ18O record[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(6): 1370-1380. |

| [23] |

Duan F C, Liu D B, Cheng H, et al. A high-resolution monsoon record of millennial-scale oscillations during late MIS3 from Wulu Cave, South-West China[J]. Journal of Quaternary Science, 2014, 29(1): 83-90. |

| [24] |

Chen S T, Wang Y J, Cheng H, et al. Strong coupling of Asian monsoon and Antarctic climates on sub-orbital timescales[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 32995. DOI:10.1038/srep32995 |

| [25] |

Shakun J D, Clark P U, He F, et al. Global warming preceded by increasing carbon dioxide concentrations during the last deglaciation[J]. Nature, 2012, 484(7392): 49-54. DOI:10.1038/nature10915 |

| [26] |

Cuffey K M, Clow G D, Steig E J, et al. Deglacial temperature history of West Antarctica[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2016, 113(50): 14249-14254. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1609132113 |

| [27] |

Hendy C H. The isotopic geochemistry of speleothems-Ⅰ. The calculation of the effects of different modes of formation on the isotopic composition of speleothems and their applicability as palaeoclimatic indicators[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1971, 35(8): 801-824. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(71)90127-X |

| [28] |

Genty D, Baker A, Massault M, et al. Dead carbon in stalagmites:Carbonate bedrock paleodissolution vs. ageing of soil organic matter. Implications for 13C variations in speleothems[J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2001, 65(20): 3443-3457. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7037(01)00697-4 |

| [29] |

章新平, 田立德, 刘晶淼, 等. 沿着三条水汽输送路径的降水中δ18O变化特征[J]. 地理学报, 2005, 25(2): 190-196. Zhang Xinping, Tian Lide, Liu Jingmiao, et al. Variations of δ18O in precipitation along three vapor transport paths[J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 2005, 25(2): 190-196. |

| [30] |

Dansgaard W. Stable isotopes in precipitation[J]. Tellus Series B:Chemical of Physical Meteorology, 1964, 16(4): 436-468. |

| [31] |

Worden J, Noone D, Bowman K, et al. Importance of rain evaporation and continental convection in the tropical water cycle[J]. Nature, 2007, 445(7127): 528-532. DOI:10.1038/nature05508 |

| [32] |

谭明, 南素兰. 中国季风区降水氧同位素年际变化的"环流效应"初探[J]. 第四纪研究, 2010, 30(3): 620-622. Tan Ming, Nan Sulan. Primary investigation on interannual changes in the circulation effect of precipitationoxygen isotopes in monsoon China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2010, 30(3): 620-622. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2010.03.21 |

| [33] |

Cruz F W, Burns S J, Karmann I, et al. Insolation-driven changes in atmospheric circulation over the past 116, 000 years in subtropical Brazil[J]. Nature, 2005, 434(7029): 63-66. DOI:10.1038/nature03365 |

| [34] |

陈隆勋, 张博, 张瑛. 东亚季风研究的进展[J]. 应用气象学报, 2006, 17(6): 711-724. Chen Longxun, Zhang Bo, Zhang Ying. Progress in research on the East Asian monsoon[J]. Journal of Applied Meteorological Science, 2006, 17(6): 711-727. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7313.2006.06.009 |

| [35] |

Rozanski K, Araguás-Araguás Luis, Gonfiantini R. Isotopic patterns in modern global precipitation[M]//Swart P K, Lohmann K C, McKenzie J eds. Climate Change in Continental Isotopic Records. Geophysical Monograph Series, 78. Washington DC: American Geophysical Union(AGU), 2013: 1-36.doi: 10.1029/GM078p0001.

|

| [36] |

Jonson K R, Ingram B L. Spatial and temporal variability in the stable isotope systematics of modern precipitation in China:Implications for paleoclimate reconstructions[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2004, 220(3-4): 365-377. DOI:10.1016/S0012-821X(04)00036-6 |

| [37] |

Cheng H, Edwards R L, Broecker W S, et al. Ice age terminations[J]. Science, 2009, 326(5950): 248-252. DOI:10.1126/science.1177840 |

| [38] |

罗维均, 王世杰, 刘秀明. 中国大气降水δ18O区域特征及其对古气候研究的意义[J]. 地球与环境, 2008, 36(1): 47-55. Luo Weijun, Wang Shijie, Liu Xiuming. Regional characteristics of modern precipitation δ18O values and implications for paleoclimate research in China[J]. Earth and Environment, 2008, 36(1): 47-55. |

| [39] |

Hesterberg R, Siegenthaler U. Production and stable isotopic composition of CO2 in a soil near Bern, Switzerland[J]. Tellus, 1991, 43B(2): 197-205. |

| [40] |

Brenninkmeijer C A M, Kraft P, Mook W G. Oxygen isotope fractionation between CO2 and H2O[J]. Chemical Geology, 1983, 1(2): 181-190. |

| [41] |

McDermott F. Palaeo-climate reconstruction from stable isotope variations in speleothems:A review[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2004, 23(7): 901-918. |

| [42] |

Fairchild L J, Smith C L, Baker A, et al. Modification and preservation of environmental signals in speleothems[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2006, 75: 105-153. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.08.003 |

| [43] |

Lachniet M S. Climatic and environmental controls on speleothem oxygen-isotope values[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2009, 28(5-6): 412-432. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.10.021 |

| [44] |

Baldini J U L, McDermott F, Fairchild I J. Spatial variability in cave drip water hydrochemistry:Implications for stalagmite paleoclimate records[J]. Chemical Geology, 2006, 235(3-4): 90-404. |

| [45] |

Mattey D, Lowry D, Duffet J, et al. A 53-year seasonally resolved oxygen and carbon isotope record from a modem Gibraltar speleothem:Reconstructed drip water and relationship to local precipitation[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2008, 269(1-2): 80-95. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.01.051 |

| [46] |

周运超, 王世杰, 谢兴能, 等. 贵州4个洞穴滴水对大气降雨响应的动力学及其意[J]. 科学通报, 2004, 49(21): 2220-2227. Zhou Yunchao, Wang Shijie, Xie Xingneng, et al. Dynamics and significance of drips in four caves in Guizhou Province in response to atmospheric rainfall[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2004, 49(21): 2220-2227. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.2004.21.015 |

| [47] |

Duan W H, Cheng H, Tan M, et al. Onset and duration of transitions into Greenland Interstadials 15.2 and 14 in Northern China constrained by an annually laminated stalagmite[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 4042-4048. |

| [48] |

Darling W G. Hydrological factors in the interpretation of stable isotopic proxy data present and past:A European perspective[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2004, 23(7-8): 743-770. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2003.06.016 |

| [49] |

Cruz F W, Karmann I, Viana O, et al. Stable isotope study of cave percolation waters in subtropical Brazil:Implications for paleoclimate inferences from speleothems[J]. Chemical Geology, 2005, 220(3-4): 245-262. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2005.04.001 |

| [50] |

Baldini J U L, McDermott F, Fairchild I J. Spatial variability in cave drip water hydrochemistry:Implications for stalagmite paleoclimate records[J]. Chemical Geology, 2006, 235(3-4): 390-404. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2006.08.005 |

| [51] |

Cobb K M, Adkins J F, Partin J W, et al. Regional-scale climate influences on temporal variations of rainwater and cave dripwater oxygen isotopes in Northern Borneo[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2007, 263(3-4): 207-220. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.08.024 |

| [52] |

McDonald J, Drysdale R, Hill D, et al. The hydrochemical response of cave drip waters to sub-annual and inter-annual climate variability, Wombeyan caves, SE Australia[J]. Chemical Geology, 2007, 244(3-4): 605-623. DOI:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2007.07.007 |

| [53] |

WAIS Divide Project Member. Precise interpolar phasing of abrupt climate change during the last ice age[J]. Nature, 2015, 520(7459): 661-665. |

| [54] |

Rasmussen S O, Seierstad I K, Andersen K K, et al. Synchronization of the NGRIP, GRIP, and GISP2 ice cores across MIS2 and palaeoclimatic implications[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2008, 27(1-2): 18-28. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2007.01.016 |

| [55] |

Kindler P, Guillevic M, Baumgartner M, et al. Temperature reconstruction from 10 to 12 kyr b2k from the NGRIP ice core[J]. Climate of the Past, 2014, 10(2): 887-902. DOI:10.5194/cp-10-887-2014 |

| [56] |

Deplazes G, Lückge A, Peterson C L, et al. Links between tropical rainfall and North Atlantic climate during the last glacial period[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2013, 6(3): 213-217. DOI:10.1038/ngeo1712 |

| [57] |

Biscaye P E, Grousset F E, Revel M, et al. Asian provenance of glacial dust(stage 2)in the Greenland Ice Sheet Project 2 Ice Core, Summit, Greenland[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 1997, 102(C12): 26765-26781. DOI:10.1029/97JC01249 |

| [58] |

Bory J M, Biscaye P E, Svensson A, et al. Seasonal variability in the origin of recent atmospheric mineral dust at North GRIP, Greenland[J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2002, 196(3-4): 123-134. DOI:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00609-4 |

| [59] |

Svensson A, Biscaye P E, Grousset F E. Characterization of Late Glacial continental dust in the Greenland Ice Core Project ice core[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research, 2000, 105(D4): 4637-4656. DOI:10.1029/1999JD901093 |

| [60] |

Ruth U, Bigler M, Röthlisberger R, et al. Ice core evidence for a very tight link between North Atlantic and East Asian glacial climate[J]. Geophysical Research Letters, 2007, 340(3): L03706. |

| [61] |

Chappellaz J, Blunler T, Raynaud D, et al. Synchronous changes in atmospheric CH4 and Greenland climate between 40 and 8 kyr BP[J]. Nature, 1993, 366(6454): 443-445. DOI:10.1038/366443a0 |

| [62] |

Rhodes R H, Brook E J, Chiang J C H, et al. Enhanced tropical methane production in response to iceberg discharge in the North Atlantic[J]. Science, 2015, 348(6238): 1016-1019. DOI:10.1126/science.1262005 |

2 Key Laboratory of Virtual Geographic Environment(Nanjing Normal University), Ministry of Education, Nanjing 210023, Jiangsu;

3 Jiangsu Center for Collaborative Innovation in Geographical Information Resource Development and Application, Nanjing 210023, Jiangsu)

Abstract

In this study, eight stalagmite δ18O records were chosen from seven caves from the Asian Summer Monsoon (ASM) region. The geographical location of these cave sites ranges from 26°N to 33°N, and 105°E to 120°E, with a sufficient spatial coverage. From north to south, sample MSD is from Hulu Cave (32°30'N, 119°10'E), XR025 from Xianren Cave (32°24'N, 107°10'E), SB46 from Sanbao Cave (31°40'N, 110°26'E), YX51 from Yongxing Cave (31°35'N, 111°14'E), QT15 from Qingtian Cave (31°20'N, 110°22'E), DSB3 from Dashibao Cave (26°05'N, 105°03'E), Wu3 and Wu32 from Wulu Cave (26°03'N, 105°05'E). Apparently, site-specific karstic conditions, microclimate, soil cover and vegetation types, etc., are strikingly different at these sites, probably inducing contrasting expressions of regional climate events. These stalagmite records, mainly spanning the late MIS3 (34~27 ka B.P.), are characterized by high-resolution data and precisely-constrained chronologies, which are suitable for detecting the internal structure of short-lived abrupt ASM changes. Generally, in our studied interval, the chronologies of these records were constrained by more than three U/Th dating results, with dating uncertainties of less than 200 years. Sampling resolution is better than 40 years or even 5 years on QT15. Millennial-scale climate events in these stalagmite records, include Dansgaard-Oeschger (DO) 5 to DO3 and Heinrich event (H) 3. Regardless of the observed resemblance between DO events, regional differences can be observed in amplitude and duration. By statistical analysis, a deviation of 0.7 ‰ in amplitude and 400 years in duration was estimated between different records. To some degree, different microclimates, karstic and environmental conditions can result in these contrasting estimations. At the same time, most (over 60%) of calculated values fall within a narrow envelope, suggesting that DO events from these stalagmite records more likely reflect a true climate signal. δ18O records of samples Wu3 from Wulu Cave, Southern China and SB46 from Sanbao Cave, Central China can be a template for these abrupt ASM changes in the late MIS3.When compared with high-and low-latitude records, the timing and frequency of ASM changes agree well with Greenland temperature variations. In detail, a high level of ASM intensity and a gradual ASM rise are evident during Stadial 5 (between DO5.1 and DO4.1) and late H3, respectively, significantly different from Greenland temperature. Such ASM response is further supported by the ice-core Ca2+ record, during which Asian winter monsoon broadly weakened. Hence, a negative correlation can be expected between Asian summer and winter monsoons. The atmospheric CH4 concentration, believed to represent tropical wetlands, however, exhibits a detailed structure similar to Greenland temperature changes during Stadial 5 and H3. It is possible that a southern hemispheric source is important for CH4 changes during cooling episodes. At the tropical Atlantic, the sediment reflectance from Cariaco Basin shows a striking resemblance to ASM variability, including those during Stadial 5 and late H3. Consequently, millennial-scale ASM variability is intimately linked to thermal and hydrological activities in low latitudes, although the initial trigger might be attributed to that around the North Atlantic. 2020, Vol.40

2020, Vol.40