2 中国科学院大学, 地球与行星科学学院, 北京 100049;

3 中国科学院南海生态环境工程创新研究院, 广东 广州 510301)

浮游有孔虫是生活在海洋表层水体中的一种微体古生物,是海洋表层水体中主要的钙质生产者之一[1]。基于浮游有孔虫同位素和Mg/Ca温度等指标的研究已经成为古海洋、古气候研究的重要手段之一[2~9]。浮游有孔虫丰度和主要优势属种的生活水深具有显著的季节性变化[10~11]。对现代浮游有孔虫生态特征的了解,如浮游有孔虫的具体生活水深以及浮游有孔虫的季节繁盛特征等,是浮游有孔虫地球化学指标古海洋环境重建应用的重要基础。由于不同海区海洋环境的差异会造成浮游有孔虫生态的地理区系差异,直接引用其他海区的生态资料应用于古海洋解释可能会造成明显的不合理性。因此,非常有必要开展相应的浮游有孔虫现代生态调查研究工作。目前,在西太平洋、大西洋等区域均进行了许多现代浮游有孔虫生态调查研究工作[10, 12~16],在南海通过沉积物捕获器[17~21]和浮游拖网[22~25]调查也开展了相应方面的研究工作,但关于现代浮游有孔虫生态资料还比较缺乏。

浮游有孔虫Globigerinoides ruber被广泛应用于表层古海洋环境重建[26~28]。G.ruber有两个形态种G.ruber sensu stricto(s.s.)和G.ruber sensu lato(s.l.)。前人[26, 29]根据二者在南海沉积物中的氧碳同位素和Mg/Ca比值差异,认为这两个形态种在南海存在显著的生态差异。推测G.ruber(s.l.)可能比G.ruber(s.s.)生活于更深的水层或更冷的季节。然而来自墨西哥湾沉积物捕获器中关于这两个G.ruber形态种的氧碳同位素分析则认为,它们之间并没有明显的生态差异[30],并质疑南海之前的研究。因此,南海现代浮游有孔虫的相关生态研究将为这个争议提供重要的证据。尽管南海之前开展了一些浮游有孔虫现代调查研究,然而这些工作多是基于沉积物捕获器,侧重关注浮游有孔虫群落及主要属种的季节性变化,对于典型浮游有孔虫和G.ruber不同形态种的水深分布了解还很少,在南海南部这方面的研究则尤其匮乏,缺少解决上述争论的直接证据。因此,本文拟利用夏季南海南部10个站位垂直拖网样品,通过详细的分层样品分析来获得典型浮游有孔虫和G.ruber两个形态种的垂直分布信息及其与现代南海海洋环境条件之间的关系。

南海处于印度季风和亚洲季风的中间区域,是典型的季风影响区。夏季盛行西南季风,冬季受到东北季风的控制,春、秋则处于季风的转换期。夏季风期间,在越南沿岸附近存在一支北向的强流,构成南沙反气旋的西翼,而西南向的婆罗洲沿岸流则构成南沙反气旋的东翼[31~32]。在夏季由于受到越南上升流的影响,温跃层抬升,造成南海南部温跃层深度西浅东深[33]。这种表层环流的季节性变化进而影响到南海南部上层水体温度、盐度、初级生产力等水文环境变化。本研究采样时间6月,正好处于夏季风开始爆发时期。

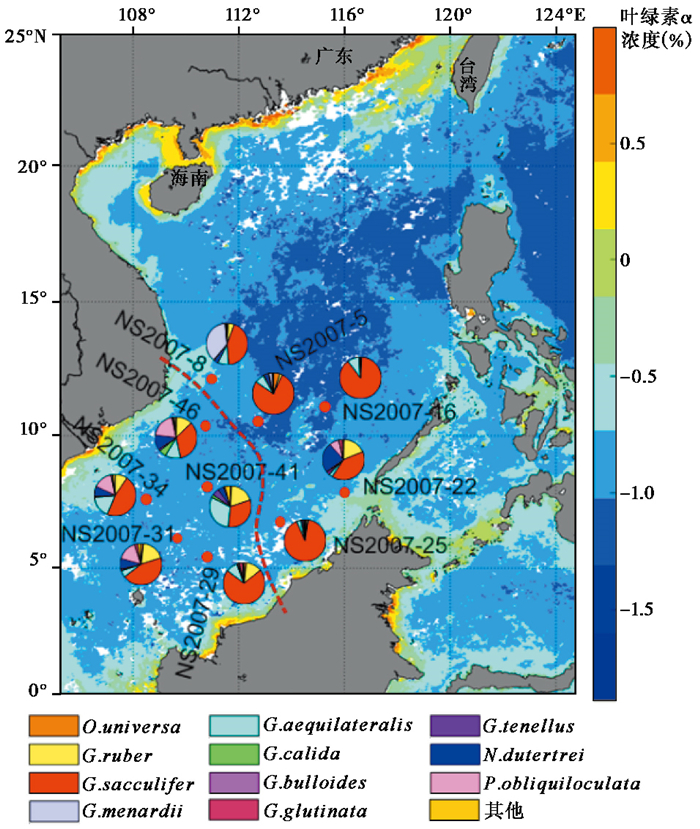

1 材料和方法研究材料来源于2007年6月中国科学院南海海洋研究所执行南海南部南沙科考调查期间所获得的浮游有孔虫垂直分层拖网样品。该拖网网口直径0.75 m,网径100 μm,网口面积0.44 m2。共在10个站位从0~250 m(部分站位0~60 m)水深获得46个拖网样品(图 1和表 1);同时进行随船温盐深(Conductance,Temperature,Depth,简称CTD)现场数据的采集。

|

图 1 取样站位位置、各站位浮游有孔虫主要属种相对含量及叶绿素α浓度分布(2007年6月) 红色曲线用以区分东部和西部站位 Fig. 1 Location of the sampling stations, abundance of dominant planktonic foraminiferal species and distribution of the Chlorophyll α concentration(June, 2007) Red dotted line is used to separate east and west stations |

| 表 1 取样站位信息 Table 1 The information of the sampling stations |

对采集的拖网样品用5 %的福尔马林固定液保存在塑料广口瓶中,防止样品中有机质的分解对浮游有孔虫壳体的保存产生的影响。在实验室预处理样品时,向样品中加入0.1 %虎红溶液染色,活体浮游有孔虫因含有原生质将会被染成玫瑰红色,可与白色死体浮游有孔虫相区分[34]。用2 mm孔径的筛网过筛去除鱼虾等大型生物,再经125 μm的标准网筛进行洗样过筛,在实体显微镜下把大于125 μm玫瑰红色的浮游有孔虫壳体挑出,鉴定并统计个数。

2 结果和讨论 2.1 浮游有孔虫总体分布特征此次调查的夏季南海南部10个站位0~250 m水层中46个浮游拖网样品共鉴定统计出17个浮游有孔虫属种,其中平均百分含量占样品总数3 %以上的优势属种有6种,分别为Globigerinoides sacculifer占65.6 %,为绝对优势种,Globigerinoides ruber占9.2 %,Neogloboquadrina dutertrei占7.6 %,Globigerinella aequilateralis占5.8 %,Globorotalia menardii和Pulleniatina obliquiloculata分别占4.0 %和3.4 %。以上6种优势属种占该区浮游有孔虫总群落的95.5 %,是典型的热带亚热带浮游有孔虫组合[12, 35]。其他零星分布的属种有Orbulina universa、Globigerinita glutinata、Globigerina calida、Globigerinoides tenellus、Hastigerinella pelagica、Globigerina bulloides、Globigerinoides conglobatus、Candeina nitida、Globorotalia scitula、Globoratalia hirsuta和Globorotalia bermudezi。以上属种组合总的特征是暖水种含量高、分布广泛,广适应性冷水种偶尔出现,表明调查区域的浮游有孔虫是以暖水种为特征的群落组合。

各站位浮游有孔虫简单分异度在8~12之间,与之前南海南部研究结果一致[36],整体上表现为在西南部陆架浅水区相对较低,东北部其他区域相对较高,这与南海北部分异度在近岸浅水区较低的结果相似[22]。在垂直分布上,整体上表现出在次表层水体中浮游有孔虫简单分异度较高,这可能和南海叶绿素高浓度通常出现在次表层的垂直分布有关[37~38],高生产力能够促进浮游有孔虫属种多样性的增强,此外,浅水区的水深可能也对该区浮游有孔虫的多样性有一定的影响。

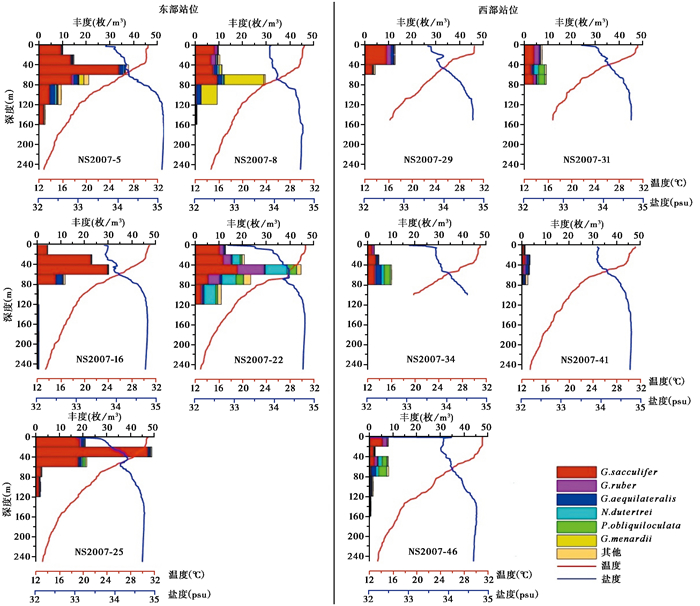

浮游有孔虫丰度在研究海区整体上呈现西南低东北高的分布趋势(图 2),最高丰度出现在NS2007-22站位,达到20.6枚/m3,而在西部站位体积丰度基本不到10枚/m3。这与崔喜江等[36]对南海南部水体浮游有孔虫的研究结果有所差异。根据图 2的CTD温度数据看以看出,东部站位混合层深度整体上比西部站位较深,推测可能和夏季风爆发造成的混合层加深有关,进而影响到水体生产力的变化,但具体影响机理还有待深入研究。

|

图 2 浮游有孔虫体积丰度各站位垂直分布图 温度和盐度数据来自随船CTD实测 Fig. 2 Comparison between the vertical distribution of planktonic foraminifera abundance with temperature and salinity Data of temperature and salinity are from onboard CTD measurements |

垂直分布上(图 2),各个站位的浮游有孔虫主要富集在0~100 m的水层中,在100 m以下都出现减少的趋势,与前人对现代浮游有孔虫的研究结果基本一致[39]。且在0~100 m水层中浮游有孔虫主要集中在60~80 m,前人研究[37]表明叶绿素浓度也在次表层水体中出现高值,因此推测可能与该海区叶绿素含量水层分布有关。此外,相同水层不同站位浮游有孔虫丰度差异也比较大,最大生物量在NS2007-22站40~60 m水层出现,高达44.59枚/m3,而在NS2007-41站相同层位仅3.16枚/m3。

NS2007-22站位和NS2007-25站位均处在近岸叶绿素浓度较高的区域(图 1),尽管该两站位表层水体的低盐特征表明受到了河流输入的影响,但这两个站位浮游有孔虫丰度均较高。前人的研究[40]也发现由于加里曼丹岛河流的输入,会在其西北侧形成一个低盐水域。然而两个站位有孔虫群落有显著差异,NS2007-22站位属种分异度高,中深层属种占比明显比NS2007-25站位高。这种差异可能与温跃层深度密切相关。NS2007-22站位正好处于巴拉巴克海峡附近,在该处南海和苏禄海水体的充分交换使得NS2007-22站位混合层加深,生产力增高,其中混合层厚度达到60 m左右,使得浮游有孔虫的生态特征和群落组合都表现出独特性,其丰度和分异度都有所增加。

2.2 浮游有孔虫优势属种水层垂直分布特征浮游有孔虫水层深度分布信息是其古海洋解释的重要前提[12, 24]。在古海洋研究中,目前有两种方法来探讨具体浮游有孔虫属种的生活水深。第一种是基于浮游有孔虫氧同位素与水体氧同位素剖面对比的方法来间接获取浮游有孔虫的平均生活水深[41~42];另一种就是根据现代垂直分层拖网调查来直接获取浮游有孔虫的生活水层信息[15, 24~25, 36, 43]。本研究主要基于后一种方法来开展研究区主要浮游有孔虫的垂直水深分布。

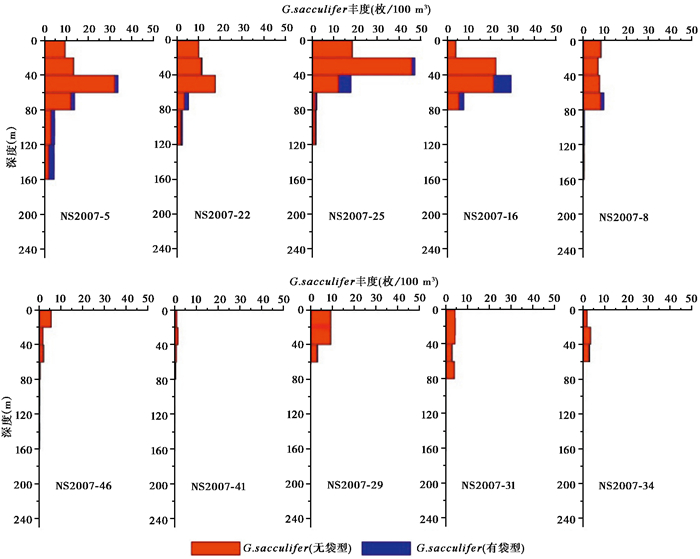

通过各个站位浮游拖网计算得出了6个优势属种在不同深度的丰度。前人认为G.ruber和G.sacculifer是典型的热带和亚热带浅层水属种,主要生活在50 m以上的水层[35]。在本次调查中,G.sacculifer基本在各个站位都占绝对优势,其主要生活水深在20~60 m,其体积丰度最大值出现在NS2007-25站20~40 m水层,丰度高达47.3枚/m-3(图 3)。G.sacculifer分为有袋型和无袋型两种生长形态,无袋型的数量要远远高于有袋型,有袋G.sacculifer的分布深度较无袋G.sacculifer较深,主要出现在40~80 m水层,可能与该种繁殖时的钙化相关。G.sacculifer在南海的水深分布特征和赤道西太平洋的结果[44]一致。

|

图 3 G.sacculifer各站位垂直分布 Fig. 3 Vertical distribution of G.sacculifer |

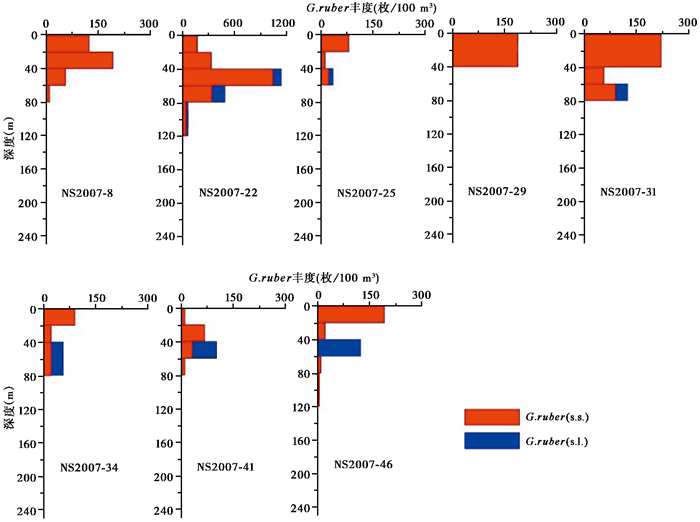

而南海南部夏季G.ruber以G.ruber(s.s.)为主,其中形态种G.ruber(s.s.)在较浅水层含量高、而形态种G.ruber(s.l.)在较深水层中含量增加(图 4),前者主要生活在0~40 m水层中,后者则主要出现在40~60 m水层中,表明夏季南海G.ruber(s.l.)比G.ruber(s.s.)生活在相对更冷和更深的水体中。前人[26, 29]根据表层沉积物中氧同位素和Mg/Ca研究结果推测G.ruber(s.l.)比G.ruber(s.s.)适宜更深的水层或更冷的季节,但在墨西哥湾的研究却未发现两个形态种之间的生态差异[30]。本研究的调查结果验证了南海G.ruber两个形态种确实存在明显的生态差异。因此,在南海进行古环境研究时,建议对G.ruber区分两个不同的形态类型。另外,在NS2007-22站位,我们发现G.ruber在40~80 m水深中大量出现,生活空间明显向下延伸。由于该处位于水体交换频繁的区域,混合层相对较深(见图 2)。因此,我们认为这可能与混合层加深导致的生活空间下移有关。

|

图 4 G.ruber各站位垂直分布图 Fig. 4 Vertical distribution of G.ruber |

通过南海南部夏季G.ruber和G.sacculifer垂直深度分布的对比(图 3和4),表明夏季该海域G.ruber平均生活深度较G.sacculifer浅,前者主要生活在0~40 m水层,而后者在20~60 m水层更为繁盛。前人[14]在西太平洋的研究表明,G.sacculifer平均生活深度较G.ruber浅,认为这种分布特征主要受到太阳光强[45]和食物来源[12]的影响。而Mohtadi等[42]利用G.ruber壳体的Mg/Ca数据推断出G.ruber生活的水深在0~30 m,生活在更浅的水层中。通过本研究,我们认为南海南部夏季G.ruber分布于较浅水层更能代表表层水体的信息。此外,在实验室培养中发现G.sacculifer和G.ruber具有不同捕食行为[12, 46],这可能是造成两者在研究海区生活水层差异的原因之一以及与Kuroyanagi和Kawahata[14]对太平洋生态研究结果不一致的原因。

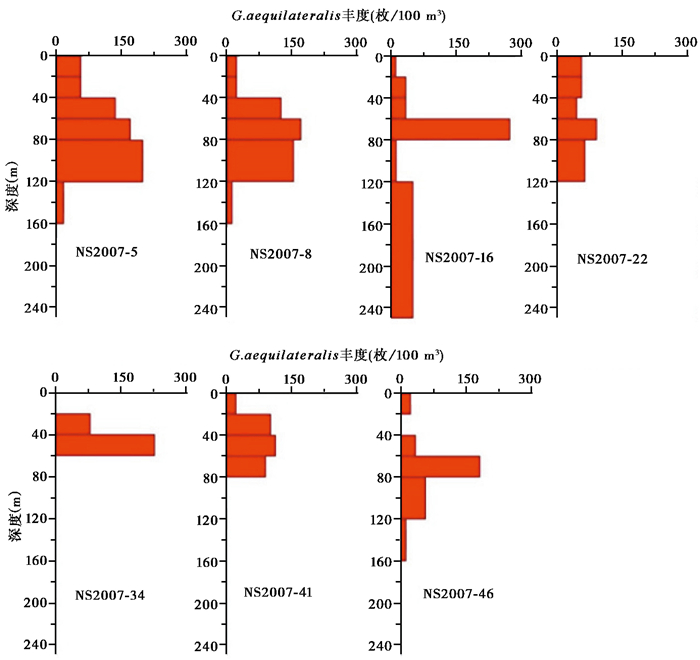

G.aequilateralis壳体带刺,常见于热带-亚热带水域,被认为是中层水分子,主要生活在50~100 m[12, 35]。本研究发现在夏季南海南部其主要出现在40~120 m的水层中(图 5),显示了其生活水层相对较深。Faber等[47]发现G.aequilateralis具有两种互相排斥且与宿主具有密切稳定关联的共生藻类型,并显示其生命过程受到不同共生藻类型的影响[48]。这可能是在调查中观察到其生活水深范围较广的原因。

|

图 5 G.aequilateralis各站位垂直分布图 Fig. 5 Vertical distribution of G.aequilateralis |

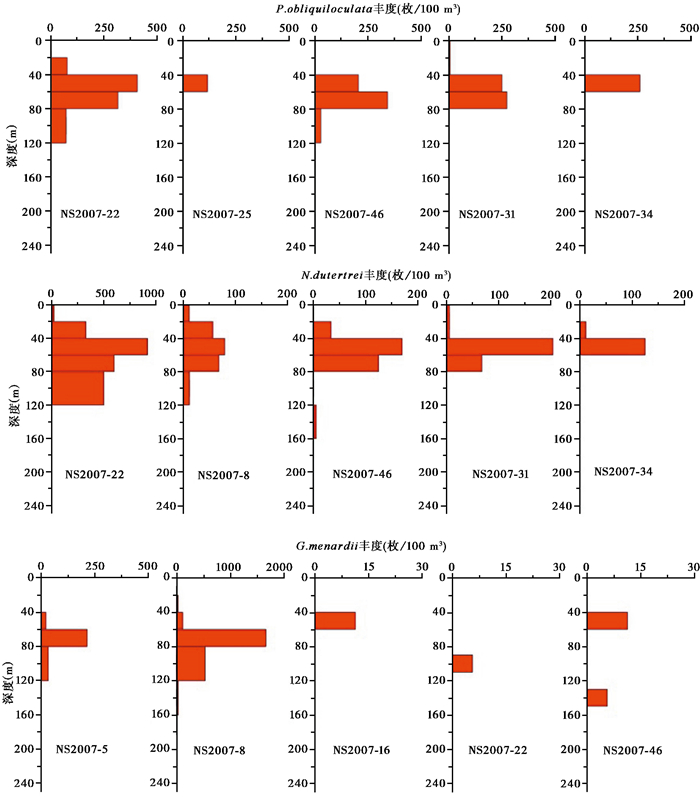

N.dutertrei和P.obliquiloculata是南海南部冰期-间冰期旋回中两个主要的浮游有孔虫属种[6]。在古环境研究中,它们均被认为是典型的温跃层属种[42],可以用作温跃层环境变化指示种。这两个属种在南海南部夏季主要生活在40~80 m的水深(图 6),且有明显伴随出现的现象。Mohtadi等[42]在爪哇岛附近海域利用N.dutertrei和P.obliquiloculata壳体钙化温度推测两者分别生活在60~80 m和60~90 m水层。这与本文的结果基本一致。此外,Field[49]和Wejnert等[50]在加利福尼亚附近海域分别通过浮游拖网和沉积物捕获器样品中浮游有孔虫研究认为N.dutertrei和P.obliquiloculata主要富集层位和温跃层有关。而在本次研究中结合随船CTD记录的温盐垂直变化数据和其生活深度的对比,可以发现在夏季南海N.dutertrei和P.obliquiloculata与温跃层之间同样具有紧密的关系,并在NS2007-22站位随温跃层的加深,生活的水层变深。

|

图 6 N.dutertrei、P.obliquiloculata和G.menardii各站位垂直分布图 Fig. 6 Vertical distributions of N.dutertrei, P.obliquiloculata and G.menardii |

在前人的研究中[35],G.menardii被认为生活在100 m以下的深层水种。而在本研究区域中,G.menardii在深水站位NS2007-5和NS2007-8站位中60 m以下水深大量存在,体积丰度最大达到1663.7枚/100 m3(见图 6),而在陆架区NS2007-29、NS2007-31、NS2007-34这3个站位没有发现。这表明水深对G.menardii平面上的分布具有一定的影响。崔喜江等[36]和万随等[44]在南海和西太平洋拖网的研究也表明G.menardii在0~250 m内都可富集,表层0~50 m壳壁较薄,个体较小,而较深水层壳体变大。这揭示了G.menardii垂直生活范围较广,与本次对南海夏季G.menardii的研究结果基本一致。

尽管本文利用浮游生物拖网资料直观的反映了区域范围内浮游有孔虫的垂直分布特征,但由于拖网取样具有瞬时性,单次的拖网调查只能了解相应季节浮游有孔虫的垂直分布情况,不一定代表其年均水深分布。另外,由于南海的表层海洋环境受季风影响变化有明显的季节转换,有必要对不同季节浮游有孔虫的水深分布生态特征进行研究,从而了解主要属种垂直深度分布的季节性变化信息及年平均分布信息。

3 结论综上所述,通过对南海南部0~250 m内不同深度浮游有孔虫的分析,结合该海区随船测得的温盐等数据,初步探讨了该区浮游有孔虫的生态分布及与海洋环境因子的关系,认识如下:

(1) 南海南部0~250 m水层共鉴定浮游有孔虫17个属种,其中G.sacculifer,G.ruber,N.dutertrei和G.aequilateralis广泛分布,G.menardii和P.obliquiloculata在部分站位含量丰富。总体分布特征是暖水种含量高,分布广泛,广适应性冷水种少见,表明调查区属于典型的热带暖水种组合。

(2) 南海南部夏季G.ruber的平均生活深度较G.sacculifer浅,G.ruber主要生活在0~40 m水深,G.sacculifer在20~60 m水层更为繁盛;次表层种N.dutertrei和P.obliquiloculata主要生活深度为40~80 m;中层水种G.aequilateralis在40~120 m都有分布。

(3) G.ruber两个形态种G.ruber(s.s.)和G.ruber(s.l.)在南海具有明显的生态差异,G.ruber(s.s.)主要出现在0~40 m水层,而G.ruber(s.l.)出现在40~60 m水层,前者更能代表表层水体的信息。

(4) 南海南部夏季浮游有孔虫的分布主要受到初级生产力和水深的影响,浮游有孔虫丰度在平面上表现为西南低、东北高,可能与混合层引起的生产力变化有关。

致谢: 感谢中国科学院南海海洋研究所实验3号科考船上工作人员在采样过程中给予的配合与帮助;中国科学院热带海洋环境动力学重点实验室提供了本研究站位温盐环境数据;审稿专家提出了建设性的修改意见,在此一并表示衷心感谢!

| [1] |

Schiebel R. Planktic foraminiferal sedimentation and the marine calcite budget[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 2002, 16(4): 13-11. |

| [2] |

Chen M T, Wang C H, Huang C Y, et al. A Late Quaternary planktonic foraminifer faunal record of rapid climatic changes from the South China Sea[J]. Marine Geology, 1999, 156(1): 85-108. |

| [3] |

Jian Z, Wang P, Chen M-P, et al. Foraminiferal responses to major Pleistocene paleoceanographic changes in the southern South China Sea[J]. Paleoceanography, 2000, 15(2): 229-243. |

| [4] |

翦知盡, 汪品先, 赵泉鸿, 等. 南海北部上新世晚期东亚冬季风增强的同位素和有孔虫证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2001, 21(5): 461-469. Jian Zhimin, Wang Pinxian, Zhao Quanhong, et al. Late Pliocene enhanced East Asian winter monsoon:Evidence of isotope and foraminifers from the northern South China Sea[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2001, 21(5): 461-469. |

| [5] |

汪品先, 翦知盡, 赵泉鸿, 等. 南海演变与季风历史的深海证据[J]. 科学通报, 2003, 48(21): 2228-2239. Wang Pinxian, Jian Zhimin, Zhao Quanhong, et al. Deep-sea evidence of the evolution of the South China Sea and monsoon history[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48(21): 2228-2239. |

| [6] |

Xiang R, Chen M, Li Q, et al. Planktonic foraminiferal records of East Asia monsoon changes in the southern South China Sea during the last 40, 000 years[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2009, 73(1-2): 1-13. |

| [7] |

Manno C, Pavlov A K. Living planktonic foraminifera in the Fram Strait(Arctic):Absence of diel vertical migration during the midnight sun[J]. Hydrobiologia, 2014, 721(1): 285-295. |

| [8] |

杨策, 徐建, 张鹏, 等. 27万年来南海南部上部水体结构和古生产力变化的古海洋学记录[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(3): 452-462. Yang Ce, Xu Jian, Zhang Peng, et al. Paleoceanographic records of upper ocean water structure and paleoproductivity in the southern South China Sea since 270 ka[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(3): 452-462. |

| [9] |

王海粟, 党皓文, 翦知盡. 中更新世转型时期南海北部上层水体结构演化特征——ODP1146站浮游有孔虫稳定同位素记录[J]. 第四纪研究, 2019, 39(2): 316-327. Wang Haisu, Dang Haowen, Jian Zhimin. Variations in the upper water structure of northern South China Sea during the mid-Pleistocene Climate Transition Period:Planktonic foraminifera oxygen isotope records of ODP site 1146[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2019, 39(2): 316-327. |

| [10] |

Yamasaki M, Sasaki A, Oda M, et al. Western equatorial Pacific planktic foraminiferal fluxes and assemblages during a La Niña year(1999)[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2008, 66(3-4): 304-319. |

| [11] |

Kim H J, Hyeong K, Park J-Y, et al. Influence of Asian monsoon and ENSO events on particle fluxes in the western subtropical Pacific[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅰ:Oceanographic Research Papers, 2014, 90: 139-151. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.002 |

| [12] |

Hemleben C, Spindler M, Anderson O R. Modern Planktonic Foraminifera[M]. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1989: 1-363.

|

| [13] |

Bárcena M A, Flores J A, Sierro F J, et al. Planktonic response to main oceanographic changes in the Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean) as documented in sediment traps and surface sediments[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2004, 53(3-4): 423-445. |

| [14] |

Kuroyanagi A, Kawahata H. Vertical distribution of living planktonic foraminifera in the seas around Japan[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2004, 53(1): 173-196. |

| [15] |

An B, Li T, Liu J, et al. Spatial distribution and controlling factors of planktonic foraminifera in the modern Western Pacific[J]. Quaternary International, 2018, 468: 14-23. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2018.01.003 |

| [16] |

Jonkers L, Hillebrand H, Kucera M. Global change drives modern plankton communities away from the pre-industrial state[J]. Nature, 2019, 570(7761): 372-375. |

| [17] |

成鑫荣, 陈荣华, 翦知盡, 等. 南海中部沉积物捕集器中浮游有孔虫的稳定同位素分析[J]. 海洋地质与第四纪地质, 2002, 22(4): 73-78. Cheng Xinrong, Chen Ronghua, Jian Zhimin, et al. Preliminary report on the stable isotopic change of plankyonic foraminifers from the sediment traps in the central South China Sea[J]. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 2002, 22(4): 73-78. |

| [18] |

Lin H L, Hsieh H-Y. Seasonal variations of modern planktonic foraminifera in the South China Sea[J]. Deep-Sea Research Part Ⅱ:Topical Studies in Oceanography, 2007, 54(14-15): 1634-1644. |

| [19] |

Wan S, Jian Z, Cheng X, et al. Seasonal variations in planktonic foraminiferal flux and the chemical properties of their shells in the southern South China Sea[J]. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2010, 53(8): 1176-1187. |

| [20] |

Lin H-L. The seasonal succession of modern planktonic foraminifera:Sediment traps observations from southwest Taiwan waters[J]. Continental Shelf Research, 2014, 84: 13-22. DOI:10.1016/j.csr.2014.04.020 |

| [21] |

Xiang R, Liu J, Wang D, et al. Seasonal flux variability of planktonic foraminifera during 2009-2011 in a sediment trap from Xisha Trough, South China Sea[J]. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 2015, 18(4): 403-413. |

| [22] |

向荣, 陈木宏, 张兰兰, 等. 南海北部秋季活体浮游有孔虫的组成与分布[J]. 地球科学——中国地质大学学报, 2010, 35(1): 1-10. Xiang Rong, Chen Muhong, Zhang Lanlan, et al. Compositions and distribution of living planktonic foraminifera in autumn waters of the northern South China Sea[J]. Earth Science-Journal of China University of Geosciences, 2010, 35(1): 1-10. |

| [23] |

Lin H-L, Sheu D-D, Yang Y, et al. Stable isotopes in modern planktonic foraminifera:Sediment trap and plankton tow results from the South China Sea[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2011, 79(1-2): 15-23. |

| [24] |

刘芳, 向荣, 张兰兰, 等. 台风过境前后南海北部水体浮游有孔虫群落变化[J]. 热带海洋学报, 2012, 31(4): 90-95. Liu Fang, Xiang Rong, Zhang Lanlan, et al. Influences of typhoon on planktonic foraminiferal fauna in the northern South China Sea[J]. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 2012, 31(4): 90-95. |

| [25] |

罗琼一, 金海燕, 翦知盡, 等. 南海现代浮游有孔虫的垂直分布及其古海洋学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(6): 1342-1353. Luo Qiongyi, Jin Haiyan, Jian Zhimin, et al. Vertical distribution of living planktonic foraminifera in the northern South China Sea and its paleoceanographic implications[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(6): 1342-1353. |

| [26] |

Wang L. Isotopic signals in two morphotypes of Globigerinoides ruber(white) from the South China Sea:Implications for monsoon climate change during the last glacial cycle[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2000, 161(3): 381-394. |

| [27] |

Tian J, Wang P, Chen R, et al. Quaternary upper ocean thermal gradient variations in the South China Sea:Implications for East Asian monsoon climate[J]. Paleoceanography, 2005, 20(4): PA4007. DOI:10.1029/2004PA001115 |

| [28] |

Steinke S, Mohtadi M, Groeneveld J, et al. Reconstructing the southern South China Sea upper water column structure since the Last Glacial Maximum:Implications for the East Asian winter monsoon development[J]. Paleoceanography, 2010, 25(2): PA2219. DOI:10.1029/2009PA001850 |

| [29] |

Steinke S, Chiu H Y, Yu P S, et al. Mg/Ca ratios of two Globigerinoides ruber (white) morphotypes:Implications for reconstructing past tropical/subtropical surface water conditions[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2005, 6(11): Q1105. DOI:10.1029/2005GC000926 |

| [30] |

Thirumalai K, Richey J N, Quinn T M, et al. Globigerinoides ruber morphotypes in the Gulf of Mexico:A test of null hypothesis[J]. Scientific Reports, 2014, 4(1): 1-7. |

| [31] |

方文东, 郭忠信, 黄羽庭. 南海南部海区的环流观测研究[J]. 科学通报, 1997, 42(21): 2264-2271. Fang Wendong, Guo Zhongxin, Huang Yuting. Observational study of the circulation in the southern South China Sea[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, 42(21): 2265-2271. |

| [32] |

李立. 南海上层环流观测研究进展[J]. 应用海洋学学报, 2002, 21(1): 114-125. Li Li. Research progress on the observation of the upper ocean circulation in the South China Sea[J]. Journal of Applied Oceanography, 2002, 21(1): 114-125. |

| [33] |

苏纪兰, 袁立业. 中国近海水文[M]. 北京: 海洋出版社, 2005: 250-272. Su Jilan, Yuan Liye. China Offshore Hydrology[M]. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2005: 250-272. |

| [34] |

Rathburn A E, Levin L A, Held Z, et al. Benthic foraminifera associated with cold methane seeps on the Northern California margin:Ecology and stable isotopic composition[J]. Marine Micropaleonology, 2000, 38(3-4): 247-266. |

| [35] |

Bé A W H. An Ecological, Zoogeographic, and Taxonomic Review of Recent Planktonic Foraminifera[M]. London: Academic Press, 1977: 1-100.

|

| [36] |

崔喜江, 向荣, 郑范, 等. 南海南部活体浮游有孔虫分布特征及其影响因素初探[J]. 热带海洋学报, 2006, 25(4): 25-30. Cui Xijiang, Xiang Rong, Zheng Fan, et al. A preliminary study of living planktonic foraminifera distribution and its affecting factors in southern South China Sea[J]. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 2006, 25(4): 25-30. |

| [37] |

黄良民. 南海不同海区叶绿素a和海水荧光值的垂向变化[J]. 热带海洋学报, 1992, 11(4): 91-97. Huang Liangmin. Vertical variations of chlorophyll a and fluorescence values of different areas in South China Sea[J]. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 1992, 11(4): 91-97. |

| [38] |

高姗.基于遥感的南海初级生产力时空变化特征与环境影响因素研究[D].北京: 中国气象科学研究院硕士论文, 2008: 8-25. Gao Shan. Spatial and Temperal Distribution of Ocean Primary Productivity and Its Relation with Oceanic Environments in the South China Sea Based on Remote Sensing[D]. Beijing: The Master's Dissertation of Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, 2008: 8-25. |

| [39] |

徐学东, 宇田理重, 土桥正也, 等. 西北太平洋黑潮主轴区浮游有孔虫的垂直分布及其古海洋学意义[J]. 第四纪研究, 1999(6): 502-510. Xu Xuedong, Uda Rie, Tsuchihashi Masaya, et al. Vertical distribution of planktonic foraminifers in Kuroshio area of NW Pacific and its paleoceanographic implications[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 1999(6): 502-510. |

| [40] |

谢华伟. 加里曼丹岛西北侧低盐水季节变化及机理分析[J]. 海洋学研究, 2011, 29(2): 3-13. Xie Huawei. Analysis of the seasonal variations and their mechanism of the low-salinity water to the northwest side of Kalimantan Island[J]. Journal of Marine Sciences, 2011, 29(2): 3-13. |

| [41] |

Huang K-F, You C-F, Lin H-L, et al. In situ calibration of Mg/Ca ratio in planktonic foraminiferal shell using time series sediment trap:A case study of intense dissolution artifact in the South China Sea[J]. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2008, 9(4): Q04016. DOI:10.1029/2007GC001660 |

| [42] |

Mohtadi M, Steinke S, Groeneveld J, et al. Low-latitude control on seasonal and interannual changes in planktonic foraminiferal flux and shell geochemistry off south Java:A sediment trap study[J]. Paleoceanography, 2009, 24(1): PA1201. DOI:10.1029/2008PA001636 |

| [43] |

唐灵刚, 向荣, 杨艺萍, 等. 东印度洋赤道南北两侧春季活体浮游有孔虫的组成与分布[J]. 微体古生物学报, 2018, 35(4): 337-347. Tang Linggang, Xiang Rong, Yang Yiping, et al. Compositions and distribution of living planktonic foraminifera in spring waters on the Equatorial transection from the eastern Indian Ocean[J]. Acta Micropalaeontologica Sinica, 2018, 35(4): 337-347. |

| [44] |

万随, 翦知盡, 成鑫荣. 赤道西太平洋冬季浮游有孔虫分布与壳体同位素特征[J]. 第四纪研究, 2011, 31(2): 284-291. Wan Sui, Jian Zhimin, Cheng Xinrong. Distribution of winter living planktonic foraminifers and characteristics to their shell's stable isotopic in the western Equatorial Pacific[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2011, 31(2): 284-291. |

| [45] |

Bijma J, Faber W W, Hemleben C. Temperature and salinity limits for growth and survival of some planktonic foraminifers in laboratory cultures[J]. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 1990, 20(20): 95-116. |

| [46] |

Spindler M, Hemleben C, Salomons J B, et al. Feeding behavior of some planktonic foraminifers in laboratory cultures[J]. The Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 1984, 14(4): 237-249. |

| [47] |

Faber W W, Anderson O R, Caron D A. Algal-foraminiferal symbiosis in the planktonic foraminifer Globigerinella aequilateralis:Ⅱ. Effects of two symbiont species on foraminiferal growth and longevity[J]. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 1989, 19(3): 185-193. |

| [48] |

Faber W W, Anderson O R, Caron D A. Algal-foraminiferal symbiosis in the planktonic foraminifer Globigerinella aequilateralis:Ⅰ. Occurrence and stability of two mutually exclusive chrysophyte endosymbionts and their ultrastructure[J]. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 1988, 18(4): 334-343. |

| [49] |

Field B D. Variability in vertical distributions of planktonic foraminifera in the California Current:Relationships to vertical ocean structure[J]. Paleoceanography, 2004, 19(2): PA2014. DOI:10.1029/2003PA000970 |

| [50] |

Wejnert K E, Pride C J, Thunell R C. The oxygen isotope composition of planktonic foraminifera from the Guaymas Basin, Gulf of California:Seasonal, annual, and interspecies variability[J]. Marine Micropaleontology, 2010, 74(1): 29-37. |

2 School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

3 Innovation Academy of South China Sea Ecology and Environmental Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510301, Guangdong)

Abstract

Ecological distribution of planktonic foraminifera has a closely relationship with upper ocean environment. In order to clear the relationship between them, we analyze 46 samples of plankton tow from upper 250 m water depth in the southern South China Sea in June 2007. A total of 17 species of planktonic foraminifera are identified in this study, therein, Globigerinoides sacculifer is the dominant species. The abundance of planktonic foraminifera is generally low in southwest and high in northwest of study area, which may be related to the change of primary productivity caused by the mixed layer. The habitat depth of Globigerinoides ruber is shallower than that of G.sacculifer. G. ruber(s.s.)distributes at water depth of 0~40 m, and G.ruber(s.l.)mainly appears at water depth of 40~60 m, which support the speculation from sediment record that the two different morphotypes of G.ruber have apparent ecological difference. Besides, it is interesting that Globigerinella aequilateralis has an extensive living depth possible because that it is controlled by two mutually exclusive symbiotic algaes. Neogloboquadrina dutertrei and Pulleniatina obliquiloculata show similar ecological preferences, often appear at the same stations and water depths. And the distribution depths of maximum abundance of N.dutertrei and P. obliquiloculata are associated with thermocline depth. Globorotalia menardii show a high abundance in deep-water sites and is rare in continental shelf sites, which suggest that water depth also can affect the distribution of planktonic foraminifera. 2019, Vol.40

2019, Vol.40