2 南京大学地理与海洋科学学院, 江苏 南京 210023)

跨大陆的文化和技术交流是人类发展进步的主要动力来源之一[1~4],早在史前时代(4200 a B.P.之前)即已存在,如粟黍、麦类作物、驯化的牛羊、青铜器、玉器、黄金、冶金技术和建筑技术等即在史前时代传播于欧亚大陆[1, 5~6]。农业对人类社会发展产生了深远的影响,不仅加强了东西方文化交流,也对全球人口数量增长做出了突出贡献[4]。农业起源是人类演化历史中最为重大的变革之一,作为世界上最早的农业起源中心,西亚的“新月形沃地”和我国的黄河流域中下游地区在10000 a B.P.前后分别出现了驯化的麦类和粟黍作物[7~11]。驯化的农作物随着人群流动、文化交流从起源中心地向外扩散[12]。公元前三千纪之后的农作物传播(被称为“史前食物全球化”)是欧亚大陆史前文化交流的重要内容,近年来成为学术界广泛关注的重大科学问题[4, 6, 13~14]。起源于黄河流域的粟黍向西传播[15~17],同时,起源于西亚的麦类作物向东传播[18~20],4500~3500 a B.P.,粟黍和麦类作物混合利用的现象主要出现在中亚东部和我国的西北地区[4]。4000 a B.P.前后,由于生产技术进步及人群流动加快,欧亚大陆文化交流速度加快,东西方两种不同的农业体系交汇于我国的甘青地区[21]。

甘青地区既是东西方文化交流的关键区域,也是我国古文明发源的重要区域之一。该区域一直是我国史前人类活动的最重要区域之一,具有完整的文化序列,自大地湾文化开始,先后经历了仰韶、马家窑等新石器时代文化。3500 a B.P.前后,铜石并用时代统一的齐家文化裂变为包括寺洼、辛店、卡约、诺木洪和四坝、沙井等青铜时代多元文化并存的格局[22~26]。由于该区域的重要地位,国内外学者在该区域开展了大量的关于史前中西交流的学术研究,研究结果显示,4000 a B.P.前后东西方文化交流强度增加,大小麦、青铜器等先后传入甘青地区[27];齐家文化(4300~3500 a B.P.)作为甘青地区4000 a B.P.前后分布最广泛的史前文化类型,持续时间长、影响范围广,麦类作物在齐家文化时期传入甘青地区,成为粟黍农业的有效补充[4]。通过研究齐家文化时期的农业结构,能够探究东西方文化的交流状况[28~31]。

甘青地区齐家文化时期已开展的植物大遗存研究主要集中在青海省东北部和甘肃河西走廊地区。齐家文化早期,麦类作物首次出现于甘青地区西部以粟黍为主的农业生产活动中,农业结构开始趋于复杂化[15, 32~37]。3500 a B.P.前后,中原地区多个遗址均发现了麦类作物遗存[38~43]。那么,在麦类作物传入甘青地区西部之后,向东经甘青地区东部进入中原地区的路线上,迄今尚未有植物考古学研究。但是,作为甘青地区最早被粟黍农业影响的区域,甘青地区中、东部仅有堡子坪遗址[16]、李家坪遗址[32]和鱼儿坬遗址[44]3个遗址的植物考古研究工作,而且前期的研究工作主要集中于单个遗址或区域地貌单元内部,对认识部分地貌单元的农业发展状况有重要意义[16, 32~37, 44~45]。厘清史前跨区域农业文化交流需要在甘青地区中、东部地区开展大量的植物考古学研究工作。同时,甘青地区跨域多个地貌单元、齐家文化前后延续800年之久[31],目前尚未有齐家文化不同发展阶段、不同分布区域农业的扩张与强化过程研究。

本文选择了甘青地区中、东部地区7处齐家文化时期的考古遗址,基于浮选获取的植物大化石,结合甘青地区已开展的相关研究成果,探究齐家文化时期(4000 a B.P.前后)甘青地区东西部先民的农业结构差异,并进一步探讨甘青地区4000 a B.P.前后农业结构变化的影响因素,为史前跨区域农业文化交流补充关键数据。

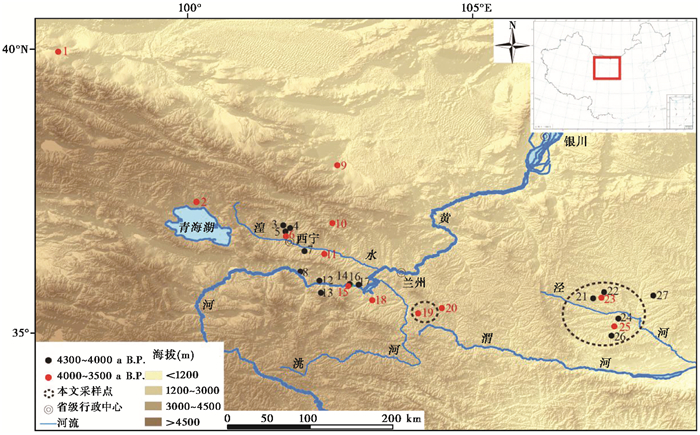

1 研究区概况考古学意义的甘青地区,包括甘肃省和青海省东北部。该地区自东向西由黄土高原向青藏高原过渡,地势由东向西逐渐升高(图 1);该区域地处我国青藏高寒区、东部季风区和西北干旱区的交汇地带,自然环境具有明显的过渡性,在各地貌单元内气候条件差异显著,气候分别以半湿润、半干旱及干旱为主,年均温在- 8.5~14.8 ℃之间,年均降水量在50~860 mm之间(图 1)[46]。由地貌差异和气候条件导致的地表植被、生态环境差异也较为明显。在甘青地区东部的陇东盆地,气候以东亚季风影响下的半湿润气候为主,年均温7~10 ℃,降水量为350~650 mm[44];在甘青地区西部的河西走廊地区,气候属于大陆性干旱-半干旱气候,年均温2~6 ℃,年均降水量50~200 mm[47];在青海省东北部,气候属于温带大陆性气候,年均温3~5 ℃,年均降水量350~450 mm[48]。

|

图 1 甘青地区开展植物考古研究的齐家文化时期遗址 1—火烧沟遗址(Huoshaogou site);2—沙柳河桥东遗址(Shaliuheqiaodong site);3—阿家村遗址(Ajiacun site);4—喇嘛刺坡遗址(Lamacipo site);5—杨家寨阳坡根遗址(Yangjiazhaiyangpogen site);6—下孙家寨遗址(Xiasunjiazhai site);7—东村(甲)遗址(Dongcunjia site);8—中滩遗址(Zhongtan site);9—皇娘娘台遗址(Huangniangniangtai site);10—金蝉口遗址(Jinchankou site);11—赵家庄遗址(Zhaojiazhuang site);12—贡什加遗址(Gongshenjia site);13—才让当高遗址(Cairangdanggao site);14—辛家遗址(Xinjia site);15—喇家遗址(Lajia site);16—清泉旱台遗址(Qingquanhantai site);17—鄂家遗址(Ejia site);18—李家坪遗址(Lijiaping site);19—冠子嘴遗址(Guanzizui site);20—堡子坪遗址(Buziping site);21—上面坬遗址(Shangmiangua site);22—堡子壕遗址(Buzihao site);23—后河马沟沟遗址(Houhemagougou site);24—东坡遗址(Dongpo site);25—桥村遗址(Qiaocun site);26—蒋家嘴遗址(Jiangjiazui site);27—鱼儿坬遗址(Yu'ergua site) Fig. 1 Archaeological sites for archaeobotanical research during Qijia Period in Gansu-Qinghai region |

本文研究的7处齐家文化时期的遗址点分布于甘青地区的东部(6处,见图 1中21~26号)和中部(1处,见图 1中19号)。甘青地区东部的遗址分别是镇原县上面坬遗址(35.64°N,107.13°E)、堡子壕遗址(35.71°N,107.30°E)和后河马沟沟遗址(35.634°N,107.27°E),灵台县东坡遗址(35.26°N,107.57°E)、桥村遗址(35.15°N,107.49°E)和蒋家嘴遗址(35.04°N,107.44°E) (见图 1中21~26号);甘青地区中部的遗址是临洮县冠子嘴遗址(35.34°N,104.03°E) (见图 1中19号)。

2 材料与方法 2.1 植物大遗存获取与鉴定方法我们于2011~2017年先后在甘青地区新调查和发现齐家文化遗址7处[49],在不同遗址的灰坑或文化层中共采集浮选土样23份(7~14 L不等),平均每份样品9 L,共计208 L。采样过程中遵循两个原则:一是采样单位均未受到二次埋藏堆积和现代人类活动扰动;二是采样单位有明确断代遗物(典型陶片),避免对遗迹单位的相对年代认识不清。调查过程中对采样遗址进行GPS定位并记录遗址周边的地貌、水文环境。采集土样全部通过水波浮选仪浮选,比重大于水的骨头、陶片等重浮物则落于水箱内的筛网上,用样品袋收集、编号;利用80目筛网收集轻浮物(比重小于水的物质),收集后用纱布包裹,在阴凉通风处晾干。在兰州大学西部环境教育部重点实验室的环境考古实验室分别用5目、10目、18目、26目、35目和80目的筛网进行初筛,然后在体视显微镜下初选和鉴定,部分炭化种子在中国社会科学院考古研究所科技考古中心植物考古实验室进行种属鉴定。

2.2 AMS 14C测年在考古调查中,我们首先基于遗迹单位里的包裹物进行考古年代判定。在炭化植物种子鉴定后,分别选取上面坬遗址、桥村遗址和蒋家嘴遗址获得的5~10粒炭化农作物种子(粟或黍)进行AMS 14C测年。部分AMS 14C测年的石墨制靶过程在兰州大学西部环境教育部重点实验室的年代学实验室完成,部分AMS 14C测年的石墨制靶过程在北京大学考古文博学院年代实验室完成,年代测定在北京大学加速质谱实验室完成。年代测定所用的14C半衰期为5568年,“a B.P.”为距1950年。所测年的14C年代全部通过Calib 7.0.4校正软件中的Intcal 13树轮校正曲线,将其转换为日历年代[50~51]。

3 结果7处齐家文化遗址采集的23份浮选土样共鉴定出炭化植物种子13567粒,粟、黍共12513粒,占炭化植物种子总数的92.23 % (表 1)。其中,农作物包括粟(Setaria italica;图 2a)、黍(Panicum miliaceum;图 2b)和大豆(Glycine max),杂草类种子包括狗尾草(Setaria viridis;图 2c)、草木樨(Melilotus officinalis;图 2d)、堇菜(Viola verecumda;图 2e)、猪毛菜(Salsola collina;图 2f)、锦葵(Malva sinensis;图 2g)、牻牛儿苗(Erodium stephanianum;图 2h)、野燕麦(Avena fatua;图 2i)、藜(Chenopodium hybridum)、虫实(Corispermum hyssopifolium)、地肤(Kochia scoparia)、黄芪(Astragalus membranaceus)、马蔺(Iris lactea)、苔草(Carexhetero stachya)、水棘针(Amethystea caerulea)和酸模叶蓼(Polygonum lapathifolium)。

| 表 1 7处齐家文化遗址出土炭化植物种子统计表 Table 1 Charred plant seeds identified from 7 archaeological sites during Qijia Period in Gansu-Qinghai region |

|

图 2 7处齐家文化遗址出土部分炭化植物种子(比例尺为1 mm) (a)—蒋家嘴遗址,粟(Jiangjiazui site,Foxtail Millet);(b)—蒋家嘴遗址,黍(Jiangjiazui site,Broomcorn Millet);(c)—蒋家嘴遗址,狗尾草(Jiangjiazui site,Green Bristlegrass);(d)—后河马沟沟遗址,草木樨(Houhemagougou site,Daghestan Sweetclover);(e)—堡子壕遗址,堇菜(Buzihao site,Serrate Violet);(f)—上面坬遗址,猪毛菜(Shangmiangua site,Common Russianthistle);(g)—堡子壕遗址,锦葵(Buzihao site,Malva Sinensis);(h)—上面坬遗址,牻牛儿苗(Shangmiangua site,Common Heron's Bill);(i)—上面坬遗址,野燕麦(Shangmiangua site,Avena Fatua) Fig. 2 Charred plant seeds identified from 7 archaeological sites during Qijia Period in Gansu-Qinghai region(scale bar:1 mm) |

从出土农作物的绝对数量来看(表 1),7个遗址中粟所占比例均最高,后河马沟沟遗址、桥村遗址、东坡遗址、上面坬遗址粟所占比重均高达90 %以上,分别为100 %、93.7 %、92.8 %和92.7 %;冠子嘴遗址、堡子壕遗址、蒋家嘴遗址粟所占农作物的比重也达到80 %左右,分别为85.0 %、80.0 %和79.3 %;另外,2粒大豆分别出自桥村遗址、蒋家嘴遗址。杂草种子中,除狗尾草、草木樨、苔草出土概率较高,分别为72.9 %、11.6 %和8.4 %外,其余杂草的出土概率均小于2 %。

对陇东盆地的上面坬遗址、桥村遗址和蒋家嘴遗址出土的粟、黍进行AMS 14C年代测年,结果分别为3845±30 a B.P.、3635±25 a B.P.和3835±25 a B.P.,树轮校正后分别为4279±125 cal. a B.P.、3972±100 cal. a B.P.和4277±127 cal. a B.P.(2 Sigma)(表 2)。

| 表 2 齐家文化遗址AMS 14C年代测年结果 Table 2 14C dating results on Qijia archaeological sites in Gansu-Qinghai region |

粟黍作物和麦类作物在欧亚大陆的传播是4000 a B.P.前后中西方文化交流的重要内容[21]。起源于西亚地区的麦类作物于5000 a B.P.沿“亚洲内陆山地走廊”向东传入塔吉克斯坦和哈萨克斯坦等地区,后于4000 a B.P.前后传入我国境内[53]。粟、黍作物于5500 a B.P.前随马家窑文化在甘青地区传播,并于4500 a B.P.之前传入河西走廊,随后沿“丝绸之路”路线和“欧亚草原”路线向新疆和中亚传播[19]。两种不同的农业体系于4000 a B.P.前后交汇于我国的甘青地区。随着麦类作物的传入,甘青地区4000 a B.P.前后的农业结构、生业模式产生了重要技术革命性的变化。

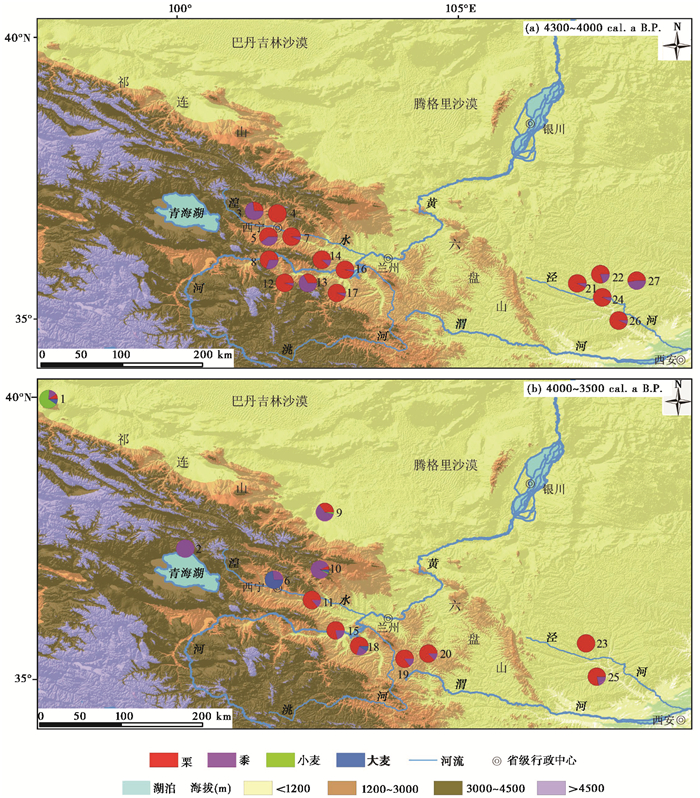

4000 a B.P.前,甘青地区东部齐家文化遗址(上面坬遗址、堡子壕遗址、东坡遗址、蒋家嘴遗址、鱼儿坬遗址[44])的浮选结果均显示(图 3a),以粟、黍为主的北方旱作农业是甘青地区东部地区齐家文化时期最主要的生业模式之一,粟、黍也是先民最主要的食物来源。同时,以上5处遗址粟的绝对数量均大于黍,粟、黍比分别为12.8、4.0、12.9、3.8和1.1,炭化植物种子结果显示粟应为当时人类最主要的食物来源。4000 a B.P.前甘青地区其他齐家文化时期考古遗址(图 3a)的浮选结果均显示,粟、黍是齐家文化早期(4000 cal.a B.P.前)的主要农作物。如青海省东北部的阿家村遗址(3975±107 cal. a B.P.)[17]、喇嘛刺坡遗址[34]、杨家寨阳坡根遗址(4064±83 cal. a B.P.)[17]、东村(甲)遗址[34]、中滩遗址(3975±107 cal. a B.P.)[17]、贡什加遗址(3955±112 cal. a B.P.)[17]、才让当高遗址[34]、辛家遗址(4035±109 cal. a B.P.)[17]、清泉旱台遗址[36]和鄂家遗址[36]。其中,喇嘛刺坡遗址[34]、杨家寨阳坡根遗址[17]、东村(甲)遗址[34]、中滩遗址[17]、贡什加遗址[17]、辛家遗址[17]、清泉旱台遗址[36]、鄂家遗址[36]和鱼儿坬遗址[44]的浮选结果均显示,粟多于黍。虽然阿家村遗址和才让当高遗址的粟、黍比小于1,但因为该遗址粟黍的绝对数量很少(可鉴定炭化农作物种子分别仅有11粒和3粒),浮选结果可能未反映遗址的真实状况(图 3a)。此外,青海省东北部地区群尖盆地的梅家遗址(4162±184 cal. a B.P.)曾浮选获得大麦7粒[34]。但是,因该遗址测年材料为炭屑,没有农作物直接测年结果,这里暂不考虑。除植物大遗存外,遗址出土人骨的稳定同位素也显示了当时人群的C4食性(以粟、黍为主)。Ma等[54]对河湟地区齐家文化时期遗址先民的δ13C研究发现,人和杂食动物均以C4食物为主,人骨稳定同位素的结果也印证了当时人类从事以粟黍为主的旱作农业。综上所述,炭化植物种子结果显示,甘青地区在齐家文化早期(4000 cal.a B.P.前)形成了以粟为主、黍为辅的农业结构。

|

图 3 甘青地区齐家文化4000 a B.P.前后植物遗存鉴定结果(遗址序号与图 1一致) Fig. 3 The results of identified charred seeds before and after 4000 a B.P. belonged to the Qijia Period in the Gansu-Qinghai region(Numbers are the same as Fig. 1) |

4000 cal.a B.P.后,甘青地区东、中部齐家文化遗址(后河马沟沟遗址、桥村遗址和冠子嘴遗址)的浮选结果显示,甘青地区东、中部的先民仍从事以粟黍为主的旱作农业(图 3b)。但是,甘青地区广大的中、西部地区不同程度的出现了麦类作物遗存,其中包括河西地区的火烧沟遗址(3703±126 cal. a B.P.)[15]、皇娘娘台遗址(3774±133 cal. a B.P.)[37]和东灰山遗址(3487±86 cal. a B.P.)[55],青海省东北部地区的下孙家寨遗址(3997±88 cal. a B.P.)[34]、金蝉口遗址(3730± 99 cal. a B.P.)[34]和喇家遗址(3435±25 cal. a B.P.)[33],洮河流域的李家坪遗址(3591± 106 cal. a B.P.)[32],等。同时,4000~3500 cal.a B.P.甘青地区的火烧沟遗址、磨沟墓地的人骨碳同位素信号也显示,该区域的农业活动方式为粟黍作物与麦类作物混合[4]。已发表的植物遗存相关结果说明[15,32~34,37,55],麦类作物在齐家文化中晚期开始传入河西走廊地区、青海省东北部地区和洮河流域,但其种植规模较小,粟黍农业仍是当时的主要农业方式(图 3b)。相较于齐家文化早期的粟黍农业,麦类作物在齐家文化晚期的传入使得当地的农业结构趋于复杂化。此外,除火烧沟遗址浮选的麦类作物绝对数量大于粟黍外,其余齐家文化遗址出土的麦类作物数量均远小于粟黍。麦类作物的由西向东传播导致麦类作物对粟黍作物的替代在空间上可能也逐次进行。河西走廊西部地区的主流农业方式可能已经替换为麦类作物为主(图 3b),甘青地区中部的青海省东北部地区、洮河流域等区域已在齐家文化晚期开始出现麦类作物的农业生产,而分布于甘青地区最东部的陇东地区尚未出现麦类作物。

4.2 甘青地区齐家文化时期农业结构变化的影响因素齐家文化时期甘青地区农业结构的变化,不但受控于麦类作物东向传播的时空差异,也与齐家文化不同分布区域的气候变化和特征有关,不同区域的齐家文化人群对于中西农业交流和气候变化的响应程度不同。

种植业能够为新石器时代人类提供相对稳定的食物来源,促进了人口数量的增长,人口的不断增长可能导致了人群的向外扩张[56]。伴随着人群扩张,携带了不同农作物类型的史前人类在欧亚大陆开始了跨大陆的文化交流。粟黍农作物于10000 a B.P.前后在中国北方地区开始被驯化,北京东胡林[57~59]、河北徐水县南庄头和武安县磁山等遗址分别出现了粟、黍的植物大化石或微体化石[58]。在我国北方地区前仰韶文化时期(8500~7000 a B.P.)的考古遗址普遍发现了黍、粟遗存[58];仰韶文化早期(7000~6000 a B.P.)的晋南、豫西及关中地区的遗址植物浮选结果显示,农业在生业模式中的比重增大,并逐渐形成以粟、黍耕植为主要生产方式的农业社会[60~62];仰韶中晚期(6000~5000 a B.P.),粟、黍农作物随马家窑文化的扩张继续向西传播[16],5200 a B.P.传播到河湟谷地[17],5000~4500 a B.P.向西传播到河西走廊[18],而后随“丝绸之路”和“欧亚草原”南北两条路线继续向新疆和中亚传播[63]。炭化植物种子结果显示,齐家文化早期甘青地区即已形成了以粟为主、黍为辅的农业结构,这种农业结构在黄河流域的其他地区普遍存在[61, 64~65]。粟、黍农业属于雨养农业,耕作方式简单,田间管理粗放,无需投入大量劳动力,其耕植方式极易被古人掌握。此外,我国多年农作物产量研究表明,粟的单产为2250~3750 kg/ha,而黍为750~1500 kg/ha[66~67],粟的产量远大于黍;同时,在气候条件较为干旱的甘青地区,粟较黍具有更高的水分利用效率[68],这些有利的自身条件使粟成为甘青地区齐家文化时期最主要的农作物。因此,古人在4000 a B.P.前选择了以粟为主、黍为辅的农业耕植方式。粟黍作物的西向传播为甘青地区的农业发展奠定了基础。

麦类作物于10000 a B.P.前后在西亚的新月形沃地驯化[8, 69],9000~8500 a B.P.向东传播到中亚的土库曼斯坦和巴基斯坦[70~71];8500 a B.P.后,麦类作物继续向中亚、东亚地区扩展传播,4600 a B.P.左右传播至中亚东部,此后继续向东传播至东亚地区[53, 72]。我国最早的小麦直接测年来自山东的赵家庄遗址(4450~4220 cal. a B.P.)[43, 73],甘青地区最早的麦类作物出现于河西走廊的缸缸洼遗址(3975~3711 cal. a B.P.)和火石梁遗址(4084~3844 cal. a B.P.)[15]。西向传播的粟、黍作物与东向传播的麦类作物在齐家文化时期交汇于甘青地区。麦类作物的东向传播为该地区先民选择、耕植麦类作物提供了可能。

大量古气候研究表明,4000 a B.P.前后甘青地区气候开始变冷变干[74~80],齐家文化逐渐走向衰落,农业结构也随之发生转变。但由于甘青地区空间范围较大,气候变化对该地区东、西部的影响也有所不同。以甘肃东部苏家湾剖面为例[81],9000~3800 a B.P.乔灌木花粉迅速增加,松属占绝对优势,表明当时气候相对温暖湿润。该地区的气候条件尚可满足粟、黍的种植,陇东地区的先民依然延续了前期的农业生产模式。但在甘青地区西部却与之不同,以青海湖区为例[82],4500 a B.P.前该地区植被以森林草原为主,4500 a B.P.之后气候趋于干冷,尤其到3900 a B.P.后,植被由森林草原转变为稀树草原,气候条件趋于干冷。相对麦类作物而言,粟、黍的生长需要更高的热量和水分,气候恶化导致以粟、黍为主的农业生产力下降,单一的粟、黍农业可能已经不能满足人类的食物需求。同时,麦类作物的引入为农业结构的转型提供了可能。麦类作物不但拥有更高的产量,也更能适应相对干冷的气候条件[83]。同时,甘青地区东部(遗址平均海拔1108 m)海拔较低;河西走廊地区(遗址平均海拔1615 m)和青海省东北部地区(遗址平均海拔2235 m)海拔较高。后者较高的海拔导致温度相对较低,不利于粟、黍作物的生长,而麦类作物(尤其是大麦)的耐低温生长特性使之更易于生长在海拔相对较高的河西走廊和青海省东北部地区。因此,当甘青地区西部气候趋于干冷之后,原有的粟黍农业受到影响,不能满足人类食物需要,耐低温的麦类作物被引入该区域,作为粟黍农业的有效补充,满足先民食物需求。

综上所述,中西方史前农业交流为甘青地区先民提供了粟黍作物和麦类作物耕植的技术。4000 a B.P.前后甘青地区不同区域的气候差异导致农业结构的不同,东部地区较为温暖湿润的气候条件使得该地区先民延续前期的粟黍农业方式,西部地区的气候干冷化导致先民选择耐低温的麦类作物作为粟黍农业的有效补充。

5 结论本文对甘肃中、东部7处齐家文化时期遗址的植物大遗存进行研究,将其与已有研究结果对比,分析了甘青地区齐家文化时期农业结构的时空差异及其影响因素。结果如下:

(1) 调查的7处齐家文化时期遗址出土的农作物遗存中,粟、黍占绝大多数(共计12513粒,占炭化植物种子总数的92.23 %),其中粟的数量(总计10194粒)均多于黍的数量(总计2319粒),说明甘肃东部地区齐家文化时期的古人类均以粟作农业为主,粟、黍是当地先民最主要的食物来源。

(2) 齐家文化早期,甘青地区农业结构均以种植粟、黍为主,且粟的绝对数量大于黍,这可能与粟本身的高产性和对水资源利用的高效性等生长特性有关;齐家文化晚期,甘青地区东、西部的农业结构出现分异,东部仍以粟黍农业为主(冠子嘴遗址、堡子坪遗址、桥村遗址、后河马沟沟遗址),西部河西走廊和青海省东北部农业结构开始趋于多样化,形成了粟黍农业为主、麦类农业为辅的农业结构模式。

(3) 甘青地区齐家文化时期的农业结构变化,不但受控于麦类作物东向传播的时空差异,也与齐家文化不同分布区域的气候变化和特征有关。齐家文化早期,起源于中亚的麦类作物还尚未传入甘青地区,在晚期传入青海省及河西走廊地区,但仍未传入甘肃东部地区,这与东部地区较为温暖湿润的气候条件有关。相对温暖湿润的气候条件使得粟、黍产量尚可以满足先民的生活需求,甘青地区东部的先民延续了前期的粟黍农业方式。4000 a B.P.前后西部地区的气候趋于干冷,导致先民选择耐低温、有效适应高海拔环境的麦类作物作为粟黍农业的有效补充。

致谢: 感谢审稿专家和编辑部杨美芳老师宝贵的修改意见,在此一并感谢!

| [1] |

Kuzmina E E. The Prehistory of the Silk Road[M]. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008: 810-812.

|

| [2] |

Gignoux C R, Henn B M, Mountain J L. Rapid, global demographic expansions after the origins of agriculture[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(15): 6044-6049. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914274108 |

| [3] |

Anthony D W. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language:How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World[M]. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010: 15-20.

|

| [4] |

董广辉, 杨谊时, 韩建业, 等. 农作物传播视角下的欧亚大陆史前东西方文化交流[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2017, 60(5): 530-543. Dong Guanghui, Yang Yishi, Han Jianye, et al. Exploring the history of cultural exchange in prehistoric Eurasia from the perspectives of crop diffusion and consumption[J]. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2017, 60(6): 1110-1123. |

| [5] |

Sherratt A. The Trans-Eurasian exchange: The prehistory of Chinese relations with the West[M]//Mair V. Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Honolulu: Hawaii University Press, 2006: 36-45.

|

| [6] |

Jones M K, Hunt H, Lightfoot E, et al. Food globalization in prehistory[J]. World Archaeology, 2011, 43(4): 665-675. DOI:10.1080/00438243.2011.624764 |

| [7] |

严文明. 农业发生与文明起源[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2000: 1-20. Yan Wenming. Appearance of Agriculture and Origin of Culture[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2000: 1-20. |

| [8] |

Zeder M A. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin:Origins, diffusion, and impact[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(33): 11597-11604. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0801317105 |

| [9] |

Riehl S, Zeidi M, Conard N J. Emergence of agriculture in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Iran[J]. Science, 2013, 341(6141): 65-67. DOI:10.1126/science.1236743 |

| [10] |

Lv H Y, Zhang J P, Liu K, et al. Earliest domestication of common millet(Panicum miliaceum)in East Asia extended to 10, 000 years ago[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(18): 7367-7372. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0900158106 |

| [11] |

Zhao Z J. New archaeobotanic data for the study of the origins of agriculture in China[J]. Current Anthropology, 2011, 52(S4): S295-S306. DOI:10.1086/659308 |

| [12] |

Spengler R N. Agriculture in the Central Asian Bronze Age[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2015, 28(3): 215-253. DOI:10.1007/s10963-015-9087-3 |

| [13] |

张东菊, 董广辉, 王辉, 等. 史前人类向青藏高原扩散的历史过程和可能驱动机制[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2016, 59(8): 1007-1023. Zhang Dongju, Dong Guanghui, Wang Hui, et al. History and possible mechanisms of prehistoric human migration to the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2016, 59(9): 1765-1778. |

| [14] |

Jones M K, Hunt H V, Kneale C, et al. Food Globalisation in Prehistory: The Agrarian Foundations of An Interconnected Continent[C]. British Academy, 2016: 33-45.

|

| [15] |

Dodson J R, Li X Q, Zhou X Y, et al. Origin and spread of wheat in China[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2013, 72: 108-111. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.04.021 |

| [16] |

Jia X, Dong G H, Li H, et al. The development of agriculture and its impact on cultural expansion during the late Neolithic in the western Loess Plateau, China[J]. The Holocene, 2013, 23(1): 85-92. DOI:10.1177/0959683612450203 |

| [17] |

Chen F H, Dong G H, Zhang D J, et al. Agriculture facilitated permanent human occupation of the Tibetan Plateau after 3600 BP[J]. Science, 2015, 347(6219): 248-250. DOI:10.1126/science.1259172 |

| [18] |

李水城, 水涛, 王辉. 河西走廊史前考古调查报告[J]. 考古学报, 2010(2): 229-262. Li Shuicheng, Shui Tao, Wang Hui. Report on prehistoric archaeological survey in Hexi Corridor[J]. Acta Archaeologica Sinica, 2010(2): 229-262. |

| [19] |

Liu X Y, Lightfoot E, O'Connell T C, et al. From necessity to choice:Dietary revolutions in West China in the second millennium BC[J]. World Archaeology, 2014, 46(5): 661-680. DOI:10.1080/00438243.2014.953706 |

| [20] |

马志坤, 郇秀佳, 马永超, 等. 古代淀粉遗存反映的新石器中期华北平原北部旱作农业发展状况——以河北阳原姜家梁遗址为例[J]. 第四纪研究, 2018, 38(5): 1313-1324. Ma Zhikun, Huan Xiujia, Ma Yongchao, et al. Ancient starch reveals millet farming in northern part of the North China Plain during mid-term Neolithic Period:A case study of the Jiangjialiang site[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2018, 38(5): 1313-1324. |

| [21] |

Miller A V, Usmanova E, Logvin V, et al. Subsistence and social change in Central Eurasia:Stable isotope analysis of populations spanning the Bronze Age transition[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 42: 525-538. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2013.11.012 |

| [22] |

安成邦, 陈发虎. 大地湾遗址及其文化地位[J]. 兰州大学学报:社会科学版, 2000, 28(2): 105-109. An Chengbang, Chen Fahu. Dadiwan site and its cultural status[J]. Journal of Lanzhou University(Social Sciences), 2000, 28(2): 105-109. |

| [23] |

安成邦, 王琳, 吉笃学, 等. 甘青文化区新石器文化的时空变化和可能的环境动力[J]. 第四纪研究, 2006, 26(6): 923-927. An Chengbang, Wang Lin, Ji Duxue, et al. The temporal and spatial changes of Neolithic cultures in Gansu-Qinghai region and possible environmental forcing[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2006, 26(6): 923-927. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2006.06.006 |

| [24] |

严文明. 仰韶文化研究[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 1989: 16-62. Yan Wenming. Research on Yangshao Culture[M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 1989: 16-62. |

| [25] |

李水城. 东风西渐:中国西北史前文化之进程[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 2009: 246-258. Li Shuicheng. Westward Spread of Eastern:The Process of Prehistoric Culture in Northwest of China[M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2009: 246-258. |

| [26] |

蒋超年.甘青地区青铜时代考古学文化及族属研究[D].长春: 东北师范大学硕士论文, 2011: 15-36. Jiang Chaonian. Researches on the Archaeological Culture and Ethnicity of Bronze Age in the Region of Gansu and Qinghai[D]. Changchun: The Master's Thesis of Northeast Normal University, 2011: 15-36. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10200-1012294136.htm |

| [27] |

Dong G H, Yang Y S, Liu X Y, et al. Prehistoric trans-continental cultural exchange in the Hexi Corridor, Northwest China[J]. The Holocene, 2018, 28(4): 621-628. DOI:10.1177/0959683617735585 |

| [28] |

周新郢.甘青地区中全新世环境变迁、农业活动及人类适应[D].北京: 中国科学院研究生院博士论文, 2009: 5-23. Zhou Xinying. Environmental Changes, Agricultural Activities and Human Adaptation in the Holocene in the Ganqing Region[D]. Beijing: The Doctoral's Dissertation of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2009: 5-23. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y1617744 |

| [29] |

侯光良, 刘峰贵, 刘翠华, 等. 中全新世甘青地区古文化变迁的环境驱动[J]. 地理学报, 2009, 64(1): 53-58. Hou Guangliang, Liu Fenggui, Liu Cuihua, et al. Prehistorical cultural transition forced by environmental change in mid-Holocene in Gansu-Qinghai region[J]. Acta Geographica Sinica, 2009, 64(1): 53-58. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0375-5444.2009.01.006 |

| [30] |

韩海涛.史前人类文化对环境的响应及在甘青地区的表现[D].兰州: 兰州大学硕士论文, 2005: 15-27. Han Haitao. The Response of Prehistoric Human Culture to Environment and Its Performance in Gansu and Qinghai Provinces[D]. Lanzhou: The Master's Thesis of Lanzhou University, 2005: 15-27. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y731948 |

| [31] |

谢端琚. 甘青地区史前考古[M]. 北京: 文物出版社, 2002: 15-20. Xie Duanju. Pre-historical Archaeology of Gansu and Qinghai Provinces[M]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press, 2002: 15-20. |

| [32] |

杨颖.河湟地区金蝉口和李家坪齐家文化遗址植物大遗存分析[D].兰州: 兰州大学硕士论文, 2014: 20-35. Yang Ying. The Analysis of Charred Plant Seeds at Jinchankou Site and Lijiaping Site during Qijia Culture Period in the Hehuang Region, China[D]. Lanzhou: The Master's Thesis of Lanzhou University, 2014: 20-35. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10730-1014304165.htm |

| [33] |

董广辉, 张帆宇, 刘峰文, 等. 喇家遗址史前灾害与黄河大洪水无关[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2018, 61(4): 467-475. Dong Guanghui, Zhang Fanyu, Liu Fengwen, et al. Multiple evidences indicate no relationship between prehistoric disasters in Lajia site and outburst flood in upper Yellow River valley, China[J]. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2018, 61(4): 441-449. |

| [34] |

贾鑫.青海省东北部地区新石器-青铜时代文化演化过程与植物遗存研究[D].兰州: 兰州大学博士论文, 2012: 10-130. Jia Xin. Cultural Evolution Process and Plant Remains during Neolithic-Bronze Age in Northeast Qinghai Province[D]. Lanzhou: The Doctoral's Dissertation of Lanzhou University, 2012: 10-130. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10730-1014452377.htm |

| [35] |

张小虎. 青海官亭盆地植物考古调查收获及相关问题[J]. 考古与文物, 2012(3): 26-33. Zhang Xiaohu. The result and its related issues of the investigation of archaeo-botanical remains in the Guanting Basin, Qinghai[J]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 2012(3): 26-33. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7830.2012.03.004 |

| [36] |

张小虎.中全新世黄河流域不同区域环境考古研究[D].北京: 北京大学博士论文, 2010: 1-30. Zhang Xiaohu. Mid-Holocene Environmental Archaeology Research in different regions of Huanghe River Reaches[D]. Beijing: The Doctoral's Dissertation of Peking University, 2010: 1-30. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y1775057 |

| [37] |

Zhou X Y, Li X Q, Dodson J, et al. Rapid agricultural transformation in the prehistoric Hexi Corridor, China[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 426: 33-41. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.04.021 |

| [38] |

Bao Y G, Zhou X Y, Liu H B, et al. Evolution of prehistoric dryland agriculture in the arid and semi-arid transition zone in Northern China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2018, 13(8): e0198750. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0198750 |

| [39] |

邓振华, 秦岭. 中原龙山时代农业结构的比较研究[J]. 华夏考古, 2017, 3: 98-108. Deng Zhenhua, Qin Ling. Comparative study of agricultural structure in Longshan period of Central Plains[J]. Huaxia Archaeology, 2017, 3: 98-108. |

| [40] |

赵志军. 小麦传入中国的研究——植物考古资料[J]. 南方文物, 2015(3): 44-52. Zhao Zhijun. Study on the wheat's introduction into China[J]. Cultural Relics in Southern China, 2015(3): 44-52. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-6275.2015.03.009 |

| [41] |

Liu X Y, Lister D L, Zhao Z J, et al. The virtues of small grain size:Potential pathways to a distinguishing feature of Asian wheats[J]. Quaternary International, 2016, 426: 107-119. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.02.059 |

| [42] |

Betts A, Jia Peter Weiming, Dodson J. The origins of wheat in China and potential pathways for its introduction:A review[J]. Quaternary International, 2014, 348: 158-168. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.07.044 |

| [43] |

Long T W, Leipe C, Jin G Y, et al. The early history of wheat in China from 14C dating and Bayesian chronological modelling[J]. Nature Plants, 2018, 4(5): 272-279. DOI:10.1038/s41477-018-0141-x |

| [44] |

周新郢, 李小强, 赵克良, 等. 陇东地区新石器时代的早期农业及环境效应[J]. 科学通报, 2011, 56(4): 318-326. Zhou Xinying, Li Xiaoqiang, Zhao Keliang, et al. Early agricultural development and environmental effects in the Neolithic Longdong Basin(East Gansu)[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2011, 56(4): 318-326. |

| [45] |

安成邦, 吉笃学, 陈发虎, 等. 甘肃中部史前农业发展的源流:以甘肃秦安和礼县为例[J]. 科学通报, 2010, 55(14): 1381-1386. An Chengbang, Ji Duxue, Chen Fahu, et al. Evolution of prehistoric agriculture in central Gansu Province, China:A case study in Qin'an and Li County[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2010, 55(14): 1381-1386. |

| [46] |

崔一付.甘青地区新石器时代晚期陶器贸易及其影响因素初步研究[D].兰州: 兰州大学硕士论文, 2016: 6-7. Cui Yifu. Early Ceramic Trade and Its Influence Factors During Late Neolithic in Gansu-Qinghai Region[D]. Lanzhou: The Master's Thesis of Lanzhou University, 2016: 6-7. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10730-1016723461.htm |

| [47] |

许娈.气候变化对河西走廊沙漠化影响的风险评价研究[D].兰州: 兰州大学硕士论文, 2015: 18-19. Xu Luan. The Risk Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change on Desertification in Hexi Corridor[D]. Lanzhou: The Master's Thesis of Lanzhou University, 2015: 18-19. http://cdmd.cnki.com.cn/Article/CDMD-10730-1015334630.htm |

| [48] |

张山佳, 董广辉. 青藏高原东北部青铜时代中晚期人类对不同海拔环境的适应策略探讨[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(4): 696-708. Zhang Shanjia, Dong Guanghui. Human adaptation strategies to different altitude environment during mid-late Bronze Age in northeast Tibetan Plateau[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(4): 696-708. |

| [49] |

国家文物局. 中国文物地图集[M]. 甘肃省分册. 北京: 测绘出版社,, 2011: 75-80. Bureau of National Cultural Relics. Atlas of Chinese Cultural Relics—Fascicule of Gansu Province[M]. Beijing: The Mapping Publishing Company, 2011: 75-80. |

| [50] |

Stuiver M, Reimer P J. Extended 14C data base and revised CALIB 3.0 14C age calibration program[J]. Radiocarbon, 1993, 35(1): 215-230. DOI:10.1017/S0033822200013904 |

| [51] |

Reimer P J, Baillie M G L, Bard E, et al. IntCal09 and marine09 radiocarbon age calibration curves, 0-50000 years cal BP[J]. Radiocarbon, 2009, 51(4): 1111-1150. DOI:10.1017/S0033822200034202 |

| [52] |

Dong G H, Wang Z L, Ren L L, et al. A comparative study of radiocarbon dating charcoal and charred seeds from the same flotation samples in the late Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in the Gansu and Qinghai Provinces, Northwest China[J]. Radiocarbon, 2014, 56(1): 157-163. DOI:10.2458/56.16507 |

| [53] |

Spengler R N, Willcox G. Archaeobotanical results from Sarazm, Tajikistan, an early Bronze Age settlement on the edge:Agriculture and exchange[J]. Environmental Archaeology, 2013, 18(3): 211-221. DOI:10.1179/1749631413Y.0000000008 |

| [54] |

Ma M M, Dong G H, Jia X, et al. Dietary shift after 3600 cal yr BP and its influencing factors in Northwestern China:Evidence from stable isotopes[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2016, 145: 57-70. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.05.041 |

| [55] |

Flad R, Li S C, Wu X H, et al. Early wheat in China:Results from new studies at Donghuishan in the Hexi Corridor[J]. The Holocene, 2010, 20(6): 955-965. DOI:10.1177/0959683609358914 |

| [56] |

董广辉, 张山佳, 杨谊时, 等. 中国北方新石器时代农业强化及对环境的影响[J]. 科学通报, 2016, 61(26): 2913-2925. Dong Guanghui, Zhang Shanjia, Yang Yishi, et al. Agricultural intensification and its impact on environment during Neolithic Age in Northern China[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2016, 61(26): 2913-2925. |

| [57] |

Yang X Y, Wan Z W, Perry L, et al. Early millet use in Northern China[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(10): 3726-3730. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1115430109 |

| [58] |

秦岭.中国农业起源的植物考古研究与展望[C]//北京大学文博学院, 北京大学中国考古学研究中心编.考古学研究(九).北京: 文物出版社, 2012: 260-315. Qin Ling. Paleoethnobotanical study of origin of agriculture in China[C]//School of Archaeology and Museology of Peking University, Center for the Study of Chinese Archaeology of Peking University. Archaeological Study (9). Beijing: Cultural Relics Publishing House, 2012: 260-315. http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-KGXY201200017.htm |

| [59] |

赵志军. 中国古代农业的形成过程——浮选出土植物遗存证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 73-84. Zhao Zhijun. The process of origin of agriculture in China:Archaeological evidence from flotation results[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2014, 34(1): 73-84. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-7410.2014.01.10 |

| [60] |

魏兴涛. 豫西晋西南地区新石器时代植物遗存的发现与初步研究[J]. 东方考古, 2014(0): 343-363. Wei Xingtao. The discoveries and preliminary researches of plant remains in the region of the western Henan and the southwestern Shanxi in the Neolithic Age[J]. East Asia Archaeology, 2014(0): 343-363. |

| [61] |

张健平, 吕厚远, 吴乃琴, 等. 关中盆地6000-2100 cal.aB.P.期间黍、粟农业的植硅体证据[J]. 第四纪研究,, 2010, 30(2): 287-297. Zhang Jianping, Lü Houyuan, Wu Naiqin, et al. Phytolith evidence of millet agriculture during about 6000-2100 cal.aB.P. in the Guanzhong Basin, China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2010, 30(2): 287-297. |

| [62] |

王欣, 尚雪, 蒋洪恩, 等. 陕西白水河流域两处遗址浮选结果初步分析[J]. 考古与文物, 2015(2): 100-104. Wang Xin, Shang Xue, Jiang Hongen, et al. Preliminary analysis of flotation results of two sites in Baishui River basin, Shaanxi Province[J]. Archaeology and Cultural Relics, 2015(2): 100-104. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7830.2015.02.013 |

| [63] |

Spengler R, Frachetti M, Doumani P, et al. Early agriculture and crop transmission among Bronze Age mobile pastoralists of Central Eurasia[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B:Biological Sciences, 2014, 281(1783): 20133382. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2013.3382 |

| [64] |

刘长江, 靳桂云, 孔昭宸, 等. 植物考古——种子和果实研究[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2008: 1-273. Liu Changjiang, Jin Guiyun, Kong Zhaochen, et al. Archaeobotany—Research on Seeds and Fruits[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2008: 1-273. |

| [65] |

张小虎, 夏正楷, 杨晓燕, 等. 黄河流域史前经济形态对4 kaB.P.气候事件的响应[J]. 第四纪研究, 2008, 28(6): 1061-1069. Zhang Xiaohu, Xia Zhengkai, Yang Xiaoyan, et al. Different response models of prehistoric economy to 4 kaB.P. climate event in the reaches of Huanghe River[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2008, 28(6): 1061-1069. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2008.06.011 |

| [66] |

柴岩, 冯佰利. 中国小杂粮产业发展现状及对策[J]. 干旱地区农业研究, 2003, 21(3): 145-151. Chai Yan, Feng Baili. Development status and countermeasures of China's small grain industry[J]. Agricultural Research in the Arid Areas, 2003, 21(3): 145-151. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-7601.2003.03.032 |

| [67] |

杨文治, 余存祖.黄土高原主要粮作物的生产力及增产技术体系[M]//杨文治, 余存祖.黄土高原区域治理与评价.北京: 科学出版社, 1992: 5-26. Yang Wenzhi, Yu Cunzu. Productivity and production technology system of main grain crops in Loess Plateau[M]//Yang Wenzhi, Yu Cunzu. Ecological Reconstruction and Evaluation of the Loess Plateau. Beijing: Science Press, 1992: 5-26. |

| [68] |

Seghatoleslami M J, Kafi M, Majidi I, et al. Effect of drought stress at different growth stages on yield and water use efficiency of fiveproso millet(Panicum miliaceum)genotypes[J]. JWSS-Isfahan University of Technology, 2007, 11(1): 215-227. |

| [69] |

L?sch S, Grupe G, Peters J. Stable isotopes and dietary adaptations in humans and animals at pre-pottery Neolithic Nevall? ?ori, Southeast Anatolia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology:The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, 2006, 131(2): 181-193. |

| [70] |

Harris D R, Masson V M, Berezkin Y E, et al. Investigating early agriculture in Central Asia:New research at Jeitun, Turkmenistan[J]. Antiquity, 1993, 67(255): 324-338. DOI:10.1017/S0003598X00045385 |

| [71] |

Costantini L. The first farmers in Western Pakistan:The evidence of the Neolithic agropastoral settlement of Mehrgarh[J]. Pragdhara, 2008, 18: 167-178. |

| [72] |

Doumani P N, Frachetti M D, Beardmore R, et al. Burial ritual, agriculture, and craft production among Bronze Age pastoralists at Tasbas(Kazakhstan)[J]. Archaeological Research in Asia, 2015(1): 17-32. |

| [73] |

靳桂云, 王海玉, 燕生东.山东胶州赵家庄遗址龙山文化炭化植物遗存研究[M]//中国社会科学院考古研究所科技考古中心.科技考古(第三辑).北京: 科学出版社, 2011: 36-53. Jin Guiyun, Wang Haiyu, Yan Shengdong, et al. A study on carbonized plant remains from Zhaojiazhuang site Longshan Culture in Jiaozhou, Shandong[M]//Center for Scientific Archaeology of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archaeometry(Vol. 3). Beijing: Science Press, 2011: 36-53. |

| [74] |

姚檀栋, 施雅风, Thompson L G.祁连山敦德冰芯记录的全新世气候变化[M]//施雅风, 孔昭宸.中国全新世大暖期气候与环境.北京: 海洋出版社, 1992: 210. Yao Tandong, Shi Yafeng, Thompson L G. Holocene climate changes as recorded by Dunde ice core in Qilianshan[M]//Shi Yafeng, Kong Zhaochen. Climate and Environment of Holocene Megathermal in China. Beijing: China Ocean Press, 1992: 210. |

| [75] |

Lister G S, Kelts K, Zao C K, et al. Lake Qinghai, China:Closed-basin like levels and the oxygen isotope record for ostracoda since the latest Pleistocene[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1991, 84(1-4): 141-162. DOI:10.1016/0031-0182(91)90041-O |

| [76] |

An C B, Tang L Y, Barton L, et al. Climate change and cultural response around 4000 cal yr BP in the western part of Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Quaternary Research, 2005, 63(3): 347-352. DOI:10.1016/j.yqres.2005.02.004 |

| [77] |

Yang X P, Scuderi L A. Hydrological and climatic changes in deserts of China since the Late Pleistocene[J]. Quaternary Research, 2010, 73(1): 1-9. |

| [78] |

Yang X P, Scuderi L, Paillou P, et al. Quaternary environmental changes in the drylands of China—A critical review[J]. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2011, 30(23-24): 3219-3233. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.08.009 |

| [79] |

Zhou A F, Sun H L, Chen F H, et al. High-resolution climate change in mid-Late Holocene on Tianchi Lake, Liupan Mountain in the Loess Plateau in Central China and its significance[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2010, 55(20): 2118-2121. DOI:10.1007/s11434-010-3226-0 |

| [80] |

吴文祥, 刘东生. 4000 aB.P.前后东亚季风变迁与中原周围地区新石器文化的衰落[J]. 第四纪研究, 2004, 24(3): 278-284. Wu Wenxiang, Liu Tungsheng. Variations in East Asia monsoon around 4000 aB.P. and the collapse of Neolithic cultures around Central Plain[[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2004, 24: 278-284. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1001-7410.2004.03.006 |

| [81] |

安成邦, 冯兆东, 唐领余. 黄土高原西部全新世中期湿润气候的证据[J]. 科学通报, 2003, 48(21): 2280-2287. An Chengbang, Feng Zhaodong, Tang Lingyu. Evidence of a humid mid-Holocene in the western part of Chinese Loess Plateau[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48(21): 2280-2287. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.2003.21.014 |

| [82] |

Shen J, Liu X Q, Wang S M, et al. Palaeoclimatic changes in the Qinghai Lake area during the last 18, 000 years[J]. Quaternary International, 2005, 136(1): 131-140. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.11.014 |

| [83] |

Zhao H, Huang C C, Wang H Y, et al. Mid-Late Holocene temperature and precipitation variations in the Guanting Basin, upper reaches of the Yellow River[J]. Quaternary International, 2018, 74-81. |

2 School of Geographic and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, Jiangsu)

Abstract

The interaction between the east and the west in prehistoric times and its influence on the change of human production mode is a frontier scientific problem. Gansu-Qinghai region is a key area of cultural interaction between the east and the west. Archaeological studies show that the intercontinental cultural interaction in this region began in the Qijia culture period(4300~3500 a B.P.) belonged to the Copper-Stone Age, and the production mode of the ancestors of Qijia culture from the early(4300~4000 a B.P.) to the late(4000~3500 a B.P.) changed significantly. However, the research on plant archaeology that has been carried out mainly focuses on western Gansu and eastern Qinghai, while the research on central and eastern Gansu is relatively weak, resulting in the spatiotemporal variation process of agricultural structure in the period of Qijia culture and its influencing factors are still unclear.In view of the above problems, this paper analyzes the temporal and spatial differences and its influencing factors of the agricultural structure in the Qijia culture period in Gansu-Qinghai region by studying the plant macrofossils at the sites of Qijia culture period in central and eastern Gansu Province. We collected 7 sites of Qijia culture that included Shangmiangua site(35.64°N, 107.13°E), Buzihao site(35.71°N, 107.30°E), Houhemagougou site(35.634°N, 107.27°E) in Zhenyuan County, Dongpo site(35.26°N, 107.57°E), Qiaocun site(35.15°N, 107.49°E), Jiangjiazui site(35.04°N, 107.44°E) in Lingtai County on eastern Gansu and Guanzizui site in Lintao County on central Gansu. We got 23 soil samples on central and eastern Gansu Province. 13567 of charred plant seeds were identified respectively. Based on the flotation method and AMS 14C chronometry, The results showed that in the early period of the Qijia culture, the agricultural structure in the east and west of the Gansu-Qinghai region was dominated by foxtail millet and supplemented by broomcorn millet, which may be related to the high yield of foxtail millet and the high efficiency of water usage. In the late period of Qijia culture, wheat and barley originated in West Asia were introduced into the Gansu-Qinghai region, and the agricultural structure in the west was changed to mainly millet agriculture and supplemented by wheat agriculture. However, in the eastern part of Gansu, a single agricultural structure dominated by millet was continued, which may be related to different regions' responses to climate change. Millet can satisfy people's demand.This study shows that the spatiotemporal variation of crop planting structure during the Qijia culture period in the Gansu-Qinghai region is affected by the interaction between the prehistoric east and the west, climate change and local environment and other factors, which is helpful to understand the process and mechanism of the evolution of human-land relations in the key period of the communication between the prehistoric east and the west. 2019, Vol.39

2019, Vol.39