2 中国科学院青藏高原地球科学卓越创新中心, 北京 100101;

3 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049;

4 中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所, 中国科学院脊椎动物演化与人类起源重点实验室, 北京 100044;

5 中国科学院生物演化与环境卓越创新中心, 北京 100044)

粟(谷子、小米)(Setaria italica)、黍(黄米)(Panicum miliaceum)作为东亚最早驯化的旱作农作物,为中华文明的起源和发展提供了重要的物质基础[1~2]。传统的种子遗存鉴定,在旱作农业起源研究中发挥了巨大作用[3],但大部分植物种子只有被炭化后才能保存下来,而且越是早期的大植物遗存,保存的越稀少,而且更容易腐烂、灰化,难以发现或无法发现[4~9],学术界对东亚粟、黍如何从野生种类逐步演化、变异和发展成栽培的农作物还了解较少,对粟、黍旱作农业起源时间、地点、传播存在不同观点[10~12]。能否明确粟、黍及其祖本植物植硅体的形态特点,寻找和建立明确的种类鉴定和演化过程的标准,是研究取得突破的关键之一,对于东亚农作物起源和传播研究意义重大,对世界其他地区农作物的鉴定也具有重要的借鉴意义。

从世界范围看,一些重大的农业起源研究成果,首先是研究方法上的突破。近20年来,国际上针对考古遗存中农作物鉴定问题,发展了许多新方法和新手段,综合利用了植物大化石(如炭化颗粒、小穗轴)的器官形态、微体化石的细胞形态(植硅体、淀粉、孢粉)、分子化石的分子结构和同位素特征、以及遗传物质的DNA特征等使得植物遗存的鉴定取得了长足进展[13~21]。例如美洲热带雨林地区,在很少保存大植物遗存的遗址地层中,提取出鉴定特征明确且丰富的植硅体化石等,使科学界确信美洲农业起源同其他旧大陆一样,原始农业也发生在10 ka前后的全新世早期[22]。我国利用植硅体、淀粉粒等微体化石对农作物鉴定分析方法也取得了重要进展,如粟、黍稃壳植硅体形态鉴定标志的建立[23],促进了旱作农业起源和传播的研究[17, 24~30],但如何寻找、判别众多的野生与驯化农作物植硅体、淀粉粒以及分子生物学指标,寻找不同驯化阶段、不同品种、不同作物鉴定特征,仍然是亟待突破的难题。

小穗(spikelet)作为植物的繁殖器官,不仅细胞形态相对稳定,而且是人类收获、保存的果实的一部分,与人类活动密切相关。不同禾本科植物小穗中的植硅体形态特征不同,具有分类学意义,尤其受到考古学家的重视。早期禾本科植物小穗的表皮细胞植硅体研究,集中于对形态的定性描述和分类,Bonnett[31]曾经对燕麦颖片、鞘皮进行了植硅体分析,并研究了它们在组织中的分布状况,Wynn和Smithson[32]研究了英国大量草本植物小穗中的表皮细胞及角质层的硅化类型,按照小穗中植硅体的形态和沉积位置对其进行了初步的分类,发现短细胞最早开始硅化,随后长细胞形成大量的树枝状植硅体(dendritic phytolith),推测小穗中的植硅体可能具有保护种子的作用。玉米[33]、小麦[34]和水稻[35~36]小穗中的植硅体也得到深入研究,并且广泛应用于揭示这些作物起源与传播的研究中[22, 37~38]。

粟类作物(主要指粟和黍)小穗主要由五部分构成:分别是下颖、上颖、下位外稃(不孕花外稃),上位外稃(孕花外稃)和内稃(孕花内稃)(图 1)。其中内稃可进一步分为第一花内稃和第二花内稃,但第一花内稃通常退化为膜状组织或者缺失,因此内稃一般指第二花内稃。本文中所指的稃片,均为孕花外稃和孕花内稃。

|

图 1 粟、黍小穗结构 根据Nasu等(2007)[39]和Lu等(2009)[23]改绘 Fig. 1 Spikelet structure of foxtail millet and common millet, modified from Nasu et al. (2007)[39] and Lu et al. (2009)[23] |

粟类作物小穗植硅体的研究始于20世纪80年代,Parry和Hodson[40]首先对粟的小穗植硅体进行了扫描电镜分析,发现在小穗的上表皮中发育大量的带有乳头状突起的植硅体,但未提出明确的量化鉴定标准。直到近些年,粟类作物小穗植硅体才被研究者重视起来[7, 23, 41~44],并在其他指标无法使用或难以使用的情况下,提供了重要的信息,在植物考古学领域取得了重要的进展[17, 24]。小穗中不同组织产生的植硅体类型,基本可归纳为两大类:1)短细胞哑铃型和十字型,分别生长于黍和粟的内、外颖片和不孕花外稃中;2)长细胞树枝状植硅体,由黍、粟的孕花外稃和孕花内稃中表皮长细胞硅化而成,其中尤以树枝状植硅体最具有鉴定特征和分类意义。

本文主要回顾了近年来粟类作物植硅体形态研究的进展,同时针对目前研究中存在的问题和质疑,着重讨论了粟类作物与野生近源种稃片植硅体的区别,以及植硅体和大植物遗存保存差异等问题,以期推动我国植硅体形态测量与植物考古研究的深入发展。

1 区分粟与黍小穗表皮长细胞植硅体形态稳定,属间差异明显(图 2),具有很大的分类潜力。但长期以来,表皮长细胞植硅体形态的研究始终没有突破性进展,主要原因是黍、粟小穗的不同组织,同一组织不同部位植硅体形态不仅各不相同,而且会连续变化;另一方面,稃片不同细胞层之间常常同时硅化,形成不同组合特征的细胞硅化结构,因而无法找到能够区分黍、粟的植硅体典型特征[23]。基于以上的特点,Lu等[23]通过对小穗进行解剖式分析,将稃片分为上、中、下3部分,对不同种属的同一部位进行对应观察,分析黍、粟稃片的硅化表皮细胞的形态参数,测量长细胞两侧分支的长度,并对主要形态参数进行统计检验,找到了5个可以鉴定粟、黍的明确标志,可以概括为:1)颖片和下位外稃中粟为十字型,黍为哑铃型;2)粟的孕花外稃和内稃中未被孕花外稃覆盖的部分,发育特有的乳头状突起;3)孕花外稃和内稃表皮长细胞壁:粟为Ω型,黍为η型;4)孕花外稃和内稃表皮长细胞末端:粟为交叉波纹型(短),黍为交叉指型(长);5)粟的孕花外稃和内稃表皮长细胞表面特有脊线雕纹[23]。

|

图 2 粟、黍稃片表皮长细胞植硅体形态对比 (a)粟、黍稃片表皮长细胞模式(其特点是Ω型顶端膨胀呈弧形,η型顶端平滑甚至比下部更窄),根据Ge等(2018)[45]改绘;(b,c)粟、黍种子及稃片表皮长细胞形态;(d)引自Kealhofer等(2015)[7],该文将(e,f)中所示的Ω型鉴定为η型 Fig. 2 Morphological comparison of epidermal long cell phytoliths between foxtail millet and common millet. (a)The morphological patterns of epidermal long cells of foxtail millet and common millet(characterized by the expanded ends for Ω type, flat and narrow ends for η type), modified from Ge et al. (2018)[45]; (b, c)The shape of seeds and epidermal long cells of foxtail millet and common millet; (d)Quoted from Kealhofer et al. (2015)[7], which identifed the Ω type shown in(e, f)as η type |

其中,孕花外稃和内稃表皮长细胞壁的Ω/η类型,是鉴定粟、黍的最重要特征[23],表皮长细胞形态从稃片两端、四周到中心位置,逐渐分化成ΩⅠ/ηⅠ、Ω Ⅱ/ηⅡ和ΩⅢ/ηⅢ类型,但是在稃片两端,两种植物均存在一定数量的n型未分化表皮长细胞,易与黍的η型混淆,因此为了保证鉴定的准确性,一般情况下ΩⅠ/ηⅠ不作为鉴定标志,除非在同一块碎片中也存在表皮细胞末端特征或者乳突。有学者提出狗尾草属的一些种类中也存在η类型,但是从其提供的图片来看,明显将分支末端显著膨胀的ΩⅠ/ΩⅡ型鉴定为ηⅠ/ηⅡ型(引自Kealhofer等[7]中图 3d)(图 2)。当然,也不可否认,稃片的长细胞会发生极少量的形态突变,但在有足够统计量的基础上,这些突变形态是在误差范围内的,不会对统计结果造成根本影响。从一般特征中寻找规律,是形态测量学遵循的思路,利用极少数明显变异的形态建立鉴定标志或评估标准的可靠性,是不符合统计规律的,在实际应用中也无法取得可靠结果。

|

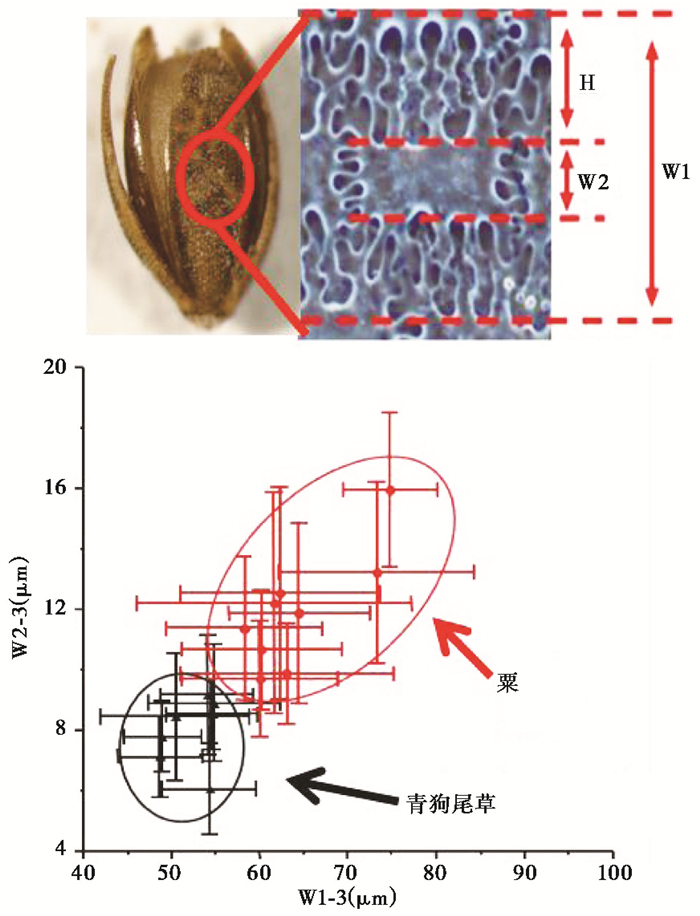

图 3 粟与青狗尾草稃片长细胞植硅体形态参数对比 W1:表皮长细胞总宽度,W1-3:ΩⅢ级表皮长细胞总宽度,W2:表皮长细胞本体宽度,W2-3:ΩⅢ级表皮长细胞本体宽度,H:表皮长细胞侧面分支长度,在Zhang等[41]基础上修改 Fig. 3 Comparison of morphological parameters of long cell phytoliths between foxtail millet and green foxtail. W1:width of epidermal long cells, W1-3:width of ΩⅢ epidermal long cells, W2:width of epidermal long cell body, W2-3:width of ΩⅢ epidermal long cell body, H:lateral branch length of epidermal long cell, after Zhang et al. [41] |

准确鉴定粟、黍,需要观察到完整的Ω/η图案。当Ω/η图案无法识别时,则需要同时观察到具有表皮细胞末端(手指/波型)的特征,或观察到乳头状突起作为关键参考,乳突在粟稃片和颖片的外表面上是常见的[40],但在黍中则不发育[23]。如以上方法皆不可鉴定,也可通过对R值的计算(交叉宽度与波动幅度的比率)进行判断[23],但需要满足一定的统计量。短细胞植硅体一定程度上也可以作为鉴定的参考,Out和Madella[43]通过对哑铃型植硅体形态分析,提出了区分粟、黍哑铃型植硅体鉴定标准,但是由于哑铃型植硅体多来自于叶片组织,在黍亚科植物中普遍存在[46],无论在自然地层还是考古地层中含量均较为丰富,使用哑铃型鉴定粟、黍,需要以沉积物中只有粟或黍为前提,因此只能用作辅助诊断特征。如上所述,最易识别的标志有3个:1)表皮长细胞两侧树枝状分支凸起的形态,粟是Ω型,黍是η型;2)相邻表皮长细胞两端交接部位形态,粟是短而圆的波浪状,而黍是长而直的手指类型;3)粟稃片发育乳头状凸起。以上3个特征,在大多数情况下可以准确鉴定粟和黍,而不需要对其形态参数进行测量统计。如果进行测量,需要注意避开粟稃片发育乳突的位置,表皮长细胞上的凸起,会显著的改变凸起周围树枝状分支的大小,从而影响统计结果。

具有鉴定特征的小穗植硅体,主要产生于种子的稃片。由于这些表皮细胞植硅体为薄片状、易碎,在自然堆积中的含量较少。在考古文化堆积中,尤其是北方新石器中、晚期的文化层中,粟类农作物种子是该类植硅体的主要来源,因此,利用Lu等[23]的鉴定标准区分考古堆积中的粟、黍遗存是准确的,也是在统计误差内可以重复检验的。另外需要指出的是,这些植硅体鉴定标志,针对的是如何有效区分粟和黍(不同属之间),而非区分粟、黍与其野生近源种(同属内不同种),例如用R值和乳突的形态判别粟与狗尾草属植物[7],不仅混淆了指标使用范围,也与原文的主旨相悖。

2 利用植硅体区分不同驯化阶段的粟、黍 2.1 区分粟与青狗尾草认识农作物的驯化过程是理解农业起源和发展的基础。农作物的驯化是指野生植物通过人工选择所产生的一系列遗传性状上的重要变化,这些变化使得驯化品种相对于野生种更加易于耕种且适于食用。粟的野生祖本植物是青狗尾草(Setaria viridis)[47],在粟驯化和栽培初期,沉积物中可能存在一定数量的青狗尾草,区分考古遗存中的粟与其野生祖本,对认识粟的起源和传播具有重要意义。

获得种子大小的宏观特征以及植硅体形态的微观特征在驯化中的变化过程,是研究植物驯化的关键,也是揭示驯化发生的有利证据[48~50]。通常情况下,种子宏观特征与植硅体微观形态是相关联的。粟和青狗尾草的种子形态相似,大致为椭圆-纺锤形,二者差别最显著的是种子中部膨胀的程度,也就是种子最长轴与最短轴的比值(长宽比,L/W),种子两端/长度变化并不明显。前人对粟和青狗尾草种子形态做过详细研究:青狗尾草的种子比粟的窄,其长宽比在3.27~1.76之间,而粟的长宽比在2.35~1.27之间,长宽比重叠约30% [39]。植硅体形态反映了植物细胞或细胞间隙的形态,也存在同种子宏观形态一致的变化,种子膨胀,稃片中部的宽度显著增加,导致稃片内细胞膨胀,细胞间隙增大,表皮长细胞植硅体的宽度因此增加。

但是植物细胞形态的分化受基因的调控[51~52],不同属的植物由于细胞形态差异明显,植硅体形态上的差异更易于区分,例如粟、黍、稗(Echinochloa sp.)、珍珠粟(Pennisetum glaucum)、高粱(Sorghum bicolor)之间,稃片植硅体的形态有显著不同[44~45];而同属植物植硅体形态则存在一定程度的相似性,尤其是野生种和驯化种之间高度相似[41],例如粟和青狗尾草,单一的形态标志往往无法胜任鉴定工作,需要借助形态测量学手段,利用统计学方法进行区分。

统计结果表明,粟和青狗尾草植硅体的显著差别,体现在稃片中部发育的ΩⅢ级表皮长细胞上。粟ΩⅢ级的尺寸(W1-3=63.8±11.8 μm,W2-3=11.8±3.2 μm,H-3=26.0±5.0 μm,N=872)明显大于青狗尾草ΩⅢ级的尺寸(W1-3=52.1±6.4 μm,W2-3=8.0±1.9 μm,H-3=22.1±2.9 μm,N=607)(W1-3、W2-3、H-3分别表示ΩⅢ级表皮长细胞总宽度、表皮长细胞本体宽度、表皮长细胞侧面分支长度)。虽然数据仍然存在约25%的重合,有一定的不确定性,但为在大植物遗存灰化或缺失的情况下鉴定粟与青狗尾草、为粟类作物起源的研究提供了一种行之有效的方法和研究思路[41](图 3)。需要强调的是,在测量统计的过程中对样本量有一定的要求[34, 53],根据Ball等[53]给出的公式,对硅化细胞的长度等一维数据的测量,至少保证每个形态有70个或更多的数据,Zhang等[41]共采集了16个品种、1479组、4437个数据进行统计,保证了每个样品的统计量达到200个以上[7]。较少的测量数据,尤其是20个以下的测量数据,很可能造成较大的统计误差,甚至得到错误的结果。

2.2 区分粟、青狗尾草与常见狗尾草属野生植物前人证据表明,生业方式从采集渔猎向农业转变的过程中,人类尝试利用并驯化过多种野生植物[54~57],例如在东亚,人类驯化水稻的同时,很可能利用或者驯化了稗草(Echinochloa sp.)[58]。中国境内有狗尾草属植物14种[59],粟类作物在驯化过程中,是否也经历了选择—尝试—选择的过程,最终发现青狗尾草更易栽培和驯化?回答这些问题,关键要发现并正确区分相关的植物遗存,排除考古遗存中杂草的干扰。

为此,在本文中,我们选取了我国北方常见的狗尾草属杂草植物,进行了初步的探索。我们对6种常见的狗尾草种类进行了取样分析,包括大狗尾草(S.faberi)、皱叶狗尾草(S. plicata)、金色狗尾草(S.pumila)(=Setaria lutescens)[59]、褐毛狗尾草(S.pallidifusca)(有学者将其视为幽狗尾草S.parviflora的变种,但因为前者较小花序,我们将S.pallidifusca作为一个独立的物种)[59~60]、两个狗尾草属的未定种(Setaria sp.)(收集于浙江省),以及Zhang等[41]文中使用的7个青狗尾草样品和5个谷子品种(不包括3个欧洲来源的品种)(表 1)。

| 表 1 植物样品详单[41] Table 1 The information of tested plant samples |

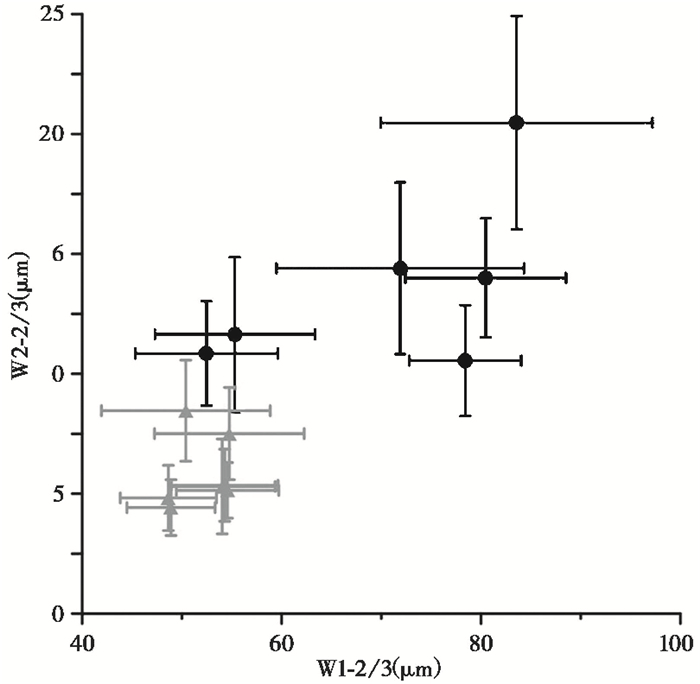

上文已经提及,Ω类型是狗尾草属植物特有的稃片表皮长细胞形态,从本文分析的几种常见狗尾草属植物来看,典型的ΩⅢ类型仅存在于粟和青狗尾草中(图 4)。因此,通过是否出现ΩⅢ类型,首先可以将粟和青狗尾草从几种常见的狗尾草属植物中区分出来;进一步测量稃片中部表皮长细胞的宽度,发现狗尾草属植物ΩⅡ级的宽度(狗尾草属植物稃片中部只发育ΩⅡ级)(W1-2=70.4±15.5 μm,W2-2=13.7±4.6 μm,N=600)显著大于青狗尾草的ΩⅢ级(W1-3=52.1±6.4 μm,W2-3=8.0±1.9 μm,N=606),甚至达到粟的ΩⅢ级水平(W1-3=63.8±11.8 μm,W2-3=11.8±3.2 μm,N=872)(图 5),判别分析的正确率可以达到85.0% (表 2)。通过本文对上述样品的形态观察和测量分析,获得了以下半定量区分标准:较宽的ΩⅡ级稃片,只来自于本文分析的几种狗尾草属野生植物,而ΩⅢ级则产自于粟或者青狗尾草。

|

图 4 青狗尾草与狗尾草属常见植物稃片的不同部位植硅体形态对比 1.大狗尾草(Setaria faberi),2.褐毛狗尾草(Setaria pallidifusca),3.皱叶狗尾草(Setaria plicata),4.狗尾草未定种(Setaria. sp.)(采自浙江天台山),5.金色狗尾草(Setaria pumila),6.狗尾草未定种(Setaria. sp.)(采自浙江上山),7.青狗尾草(S.viridis),8.粟(S. italica);每个种中的英文字母指示稃片的不同部位 Fig. 4 Morphological comparison of phytoliths in different parts of lemma and palea from green foxtail and common Setaria grasses. English letters in each sample represent different parts of the husk |

|

图 5 青狗尾草与常见狗尾草属植物种子稃片表皮长细胞宽度分布 黑色表示狗尾草属植物,灰色表示青狗尾草,W1-2/3,W2-2/3分别表示ΩⅡ/ΩⅢ级表皮长细胞的总宽度和本体宽度,青狗尾草数据来自ΩⅢ型,狗尾草属植物数据来自ΩⅡ型 Fig. 5 The width distribution of epidermal long cells in lemma and palea of green foxtail and common Setaria grasses. The black indicates data of common Setaria grasses, the gray indicates data from green foxtail, W1-2/3 and W2-2/3 indicate the total width and body width of Ω Ⅱ /Ω Ⅲ epidermal long cells, respectively. The data of green foxtail measure from Ω Ⅲ, and the data of common Setaria grasses measure from Ω Ⅱ type |

| 表 2 青狗尾草与狗尾草属植物稃片中部植硅体形态的判别分析结果 Table 2 Results of discriminant analysis for the phytolith morphology in the middle of lemma and palea in green foxtail and common Setaria grasses |

如何区分狗尾草属内各种野生植物,是未来旱作农业植硅体研究的难点之一。由于狗尾草属植物稃片长细胞的形态极为相似,单一形态的特征分析,已经很难满足属内种间植物定量鉴定的要求,充分利用统计学、形态测量学等手段,进行多指标分析,是研究的突破口,学术界也做了多方面的探索。国内有学者利用机器学习方法,对稻亚科短细胞哑铃型植硅体属间水平的鉴定特征进行了探索,是值得借鉴的方法[19],但考虑到哑铃型是黍亚科最为常见的植硅体,这一类型在黍亚科内是否具有属间或种间分类潜力,还值得进一步探讨。Weisskopf和Lee[42]观察了Setaria faberi、Setaria palmifolia(J.Koenig)Stapf.、Setaria pumilla、Setaria verticillata、Digitaria adscendans、Echinochloa colona、Echinochloa crusgalli和Paspalum conjugatum等几种杂草稃片的表皮长细胞和短细胞植硅体形态特征,证明了多指标获取鉴定特征的重要性,但是未能提出量化的鉴定标准。Kealhofer等[7]提出综合利用ΩⅢ和ΩⅠ来区分狗尾草属的杂草植物,也是值得借鉴的研究思路,但是单一的ΩⅠ型易与ηⅠ型或n型未分化表皮长细胞混淆,而且该文对ΩⅠ型的鉴定有误(见图 2d),对表皮长细胞测量数据过少,多数低于20个/参数/种[7],其结果需要进一步讨论。

2.3 区分黍与野黍子黍的野生祖本目前仍然未知[61],关于黍的早期驯化过程,驯化开始的时间、地点等问题,一直存在较大争议。野黍子(2n=36)(Panicum miliaceum subsp. ruderale(Kitag)Tzvel或Panicum ruderale(Kitag.)Chang)是黍子的野生/退化品种,广泛分布在西亚到中国的广大地区[62]。前人研究表明,它可能是黍子的野生祖先或是其杂草/野化的形式[63~64]。它的形态特征与驯化的黍子相比,具有深色的稃片、较矮的株高、稀疏和开放的花序、更多的分蘖数量、更少的小穗数量、更小的种子,同时保留了自动落粒性[63~64]。

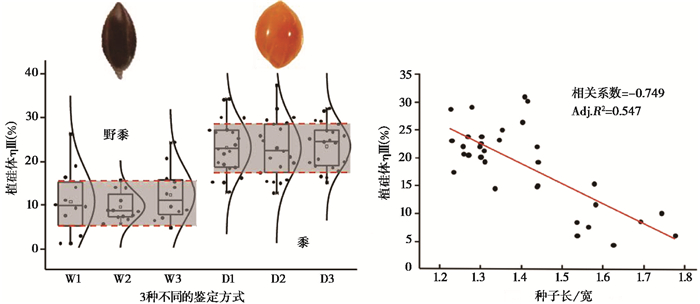

一般认为退化/野化的驯化作物具有与其野生祖本相似的生物学性状[63]。根据这一特点,利用不同的统计方法,通过计算超过10万个野黍子与驯化黍子稃片长细胞植硅体ηⅢ类型个体的数量,发现驯化品种中ηⅢ类型百分含量在误差范围内显著大于野生型的含量,且与其统计方法无关,与种子的长宽比显著负相关,种子长宽比越小,ηⅢ的含量越高[65](图 6)。进一步对比不同地区、不同环境,以及同一地区、相同环境生长的黍子和野黍子,均发现驯化品种中植硅体ηⅢ类型百分含量显著大于野生品种的含量,表明植硅体ηⅢ含量的种间差别要显著的大于种内的差别,初步排除了环境因素对黍子稃片植硅体形态的影响[65]。

|

图 6 黍与野黍稃片长细胞ηⅢ的含量对比及其与粒型的关系 W1~W3:野黍子3种不同的统计鉴定方法,D1~D3:黍子3种不同的统计鉴定方法;根据Zhang等(2018)改绘[65] Fig. 6 The comparison of the content of ηⅢ in the long cell phytoliths between Panicum miliaceum and Panicum ruderale and its relationship with grain shape. W1~W3:three statistical methods of ηⅢ in Panicum ruderale, D1~D3:three statistical methods of ηⅢ in common millet, modified from Zhang et al. (2018)[65] |

种子增大是农作物由野生到驯化的一个重要标志[49],在水稻[66]、小麦和大麦[48]中均可发现这一规律。种子在驯化过程中增大,长宽比值逐渐减小,即种子变得更宽,更饱满[67],同时稃片的宽度随之增加,导致稃片内细胞形态改变,表皮长细胞分化更为剧烈,产生了更多的ηⅢ类型。因此这一发现将黍子植硅体形态变化和农作物驯化过程连接起来,即随着驯化程度的不断加深,黍子稃片植硅体ηⅢ的含量逐渐升高,这一规律为在缺失野生祖本的情况下,探索黍子的驯化过程提供了新的途径,也为探寻其他未知祖本的谷类作物驯化过程提供了新的思路。

3 粟、黍植硅体埋藏学问题大植物遗存和微体化石互补,是植物考古学发展的趋势[42],但是同一个遗址大植物遗存和植硅体分析结果常常不一致,通常是浮选结果粟多于黍,植硅体结果黍多于粟,例如喇家遗址[68~69]、朱寨遗址[27]和关中盆地的遗址等[25, 70]。粟、黍谁在唱主角?正确的理解这一现象,有助于植物遗存资料的解释和校正,也关系到对黄河流域旱作农业和中原文化发展过程基本事实的认识[71]。

前人研究表明,无论氧化还是还原条件、无论带壳还是去壳,黍的炭化温度区间均显著小于粟,由于超过炭化温度区间的上限,种子就会灰化或爆裂变形,因此黍炭化而保存下来的几率要低于粟[72~73]。

植硅体是否也存在保存差异?是否需要对绝对数量进行校正?回答这些问题,需要通过系统的条件实验分析。初步研究表明[29],无论采用湿式还是干式灰化的方法,在保证现代样品破碎程度与地层“化石”破碎程度基本一致的情况下,1粒黍子的植硅体产量比1粒粟多约3倍,但是1 g粟的种子数平均是黍子的2.26倍,所以相同重量的粟、黍,其稃片植硅体产量在误差范围内基本相等,也就是说植硅体的绝对数量可以直接反映出黍、粟的相对重量(产量)。

植物考古的定量分析方法,如相对百分含量和标准密度都是以绝对数量为基础,而出土概率也是与植物遗存的有无相关,如果化石在形成伊始就存在保存概率上的差异,那么基于数量所做的量化分析就会存在误差[73],因此,研究大植物化石和微体化石的埋藏过程依然是植物考古研究需要深入的工作,如何建立化石出土的数量(百分含量)和单位面积农作物产量的关系,如何校正粟、黍大植物遗存和微体化石数据的关系,是值得进一步研究的课题。

4 结论与展望近几年来,基于小穗表皮长细胞植硅体形态,识别农作物及其亲缘野生植物的方法,在显示出较大潜力的同时也存在着挑战。在考古文化堆积中,应用稃片表皮长细胞形态鉴定粟、黍及其野生祖本和常见的近缘野生品种是可靠的。但是由于植硅体形态的种间相似性,对其近缘野生植物小穗植硅体的系统研究亟待开展。总结上述研究背景和问题,在粟类农作物植硅体形态学领域面临的可能突破点是:1)材料:需加强对驯化-亲缘野生植物的系统研究,尤其需要更多的国内外地方品种、不同生态型品种的对比研究;2)方法:加强几何形态测量学方法的应用,关注稃片不同部位植硅体形态的连续变化过程,关注不同生态型、不同生长阶段的种子植硅体形态变化过程;3)机制:深入开展植硅体埋藏学研究,通过系统的条件实验,明确农作物稃片植硅体统计数量与农作物产量的关系;结合遗传学的优势,通过植硅体形态在野生-驯化不同阶段的对比、不同生态型品种间的相似性和差异性的对比,揭示人类农业行为与植硅体形态变化的关系,进一步明确并量化植硅体形态变化在植物驯化过程中的意义,使小穗植硅体鉴定发挥更大的实用价值,对水稻、麦类等农作物的鉴定发挥更大的借鉴作用。

致谢: 感谢审稿专家和编辑部杨美芳老师提出的建设性修改意见!

| [1] |

Bellwood P. First Farmers:The Origin of Agricultural Societies[M]. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005: 1-332.

|

| [2] |

Crawford G. East Asian plant domestication[M]//Stark S T. East Asian Plant Domestication. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006: 77-95.

|

| [3] |

赵志军. 植物考古学:理论、方法和实践[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2010: 1-243. Zhao Zhijun. Paleoethnobotany:Theories, Methods and Practice[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2010: 1-243. |

| [4] |

Fuller D. Agricultural origins and frontiers in South Asia:A working synthesis[J]. Journal of World Prehistory, 2006, 20(1): 1-86. |

| [5] |

刘长江, 靳桂云, 孔昭宸. 植物考古——种子和果实研究[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2008: 1-273. Liu Changjiang, Jin Guiyun, Kong Zhaochen. Archaeobotany-Research on seeds and fruits[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2008: 1-273. |

| [6] |

Motuzaite-Matuzeviciute G, Hunt H V, Jones M K. Experimental approaches to understanding variation in grain size in Panicum miliaceum(broomcorn millet)and its relevance for interpreting archaeobotanical assemblages[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2012, 21(1): 69-77. DOI:10.1007/s00334-011-0322-2 |

| [7] |

Kealhofer L, Huang F, Devincenzi M, et al. Phytoliths in Chinese foxtail millet(Setaria italica)[J]. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 2015, 223: 116-127. DOI:10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.09.004 |

| [8] |

Harvey E L, Fuller D Q. Investigating crop processing using phytolith analysis:The example of rice and millets[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2005, 32(5): 739-752. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2004.12.010 |

| [9] |

Pearsall D M. Paleoethnobotany:A Handbook of Procedures(3rd)[M]. Walnut Creek: Routledge, 2015: 1-513.

|

| [10] |

Hunt H V, Linden M V, Liu X Y, et al. Millets across Eurasia:Chronology and context of early records of the genera Panicum and Setaria from archaeological sites in the old world[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2008, 17(Suppl.1): S5-S18. |

| [11] |

Hunt H V, Campana M G, Lawes M C, et al. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of broomcorn millet(Panicum miliaceum L.)across Eurasia[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2011, 20(22): 4756-4771. DOI:10.1111/mec.2011.20.issue-22 |

| [12] |

Miller N F, Spengler R N, Frachetti M. Millet cultivation across Eurasia:Origins, spread, and the influence of seasonal climate[J]. The Holocene, 2016, 26(10): 1566-1575. DOI:10.1177/0959683616641742 |

| [13] |

Fuller D Q, Qin L, Zheng Y F, et al. The domestication process and domestication rate in rice:Spikelet bases from the lower Yangtze[J]. Science, 2009, 323(5921): 1607-1610. DOI:10.1126/science.1166605 |

| [14] |

Lee G A, Crawford G W, Liu L, et al. Plants and people from the early Neolithic to Shang periods in North China[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(3): 1087-1092. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0609763104 |

| [15] |

Lu H, Yang X, Ye M, et al. Millet noodles in late Neolithic China[J]. Nature, 2005, 437(7061): 967-968. DOI:10.1038/437967a |

| [16] |

Dickau R, Ranere A J, Cooke R G. Starch grain evidence for the preceramic dispersals of maize and root crops into tropical dry and humid forests of Panama[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(9): 3651-3656. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0611605104 |

| [17] |

Yang X, Wan Z, Perry L, et al. Early millet use in Northern China[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(10): 3726-3730. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1115430109 |

| [18] |

Allaby R G, Fuller D Q, Brown T A. The genetic expectations of a protracted model for the origins of domesticated crops[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(37): 13982-13986. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0803780105 |

| [19] |

Cai Z, Ge S. Machine learning algorithms improve the power of phytolith analysis:A case study of the tribe Oryzeae(Poaceae)[J]. Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 2017, 55(4): 377-384. DOI:10.1111/jse.12258 |

| [20] |

杨晓燕. 中国古代淀粉研究:进展与问题[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(1): 196-210. Yang Xiaoyan. Ancient starch research in China:Progress and problems[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(1): 196-210. |

| [21] |

史吉晨, 介冬梅, 刘利丹, 等. 东北地区芦苇植硅体分形特征初步研究[J]. 第四纪研究, 2017, 37(6): 1444-1455. Shi Jichen, Jie Dongmei, Liu Lidan, et al. The preliminary research on the fractal characteristics of Phragmites communis phytolith in Northeast China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2017, 37(6): 1444-1455. |

| [22] |

Piperno D R, Flannery K V. The earliest archaeological maize(Zea mays L.)from highland Mexico:New accelerator mass spectrometry dates and their implications[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001, 98(4): 2101-2103. DOI:10.1073/pnas.98.4.2101 |

| [23] |

Lu H Y, Zhang J P, Wu N Q, et al. Phytoliths analysis for the discrimination of Foxtail millet(Setaria italica)and Common millet(Panicum miliaceum)[J]. PLoS ONE, 2009, 4(2): e4448. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0004448 |

| [24] |

Lu H Y, Zhang J P, Liu K B, et al. Earliest domestication of common millet(Panicum miliaceum)in East Asia extended to 10, 000 years ago[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(18): 7367-7372. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0900158106 |

| [25] |

Zhang J, Lu H, Wu N, et al. Phytolith evidence for rice cultivation and spread in mid-late Neolithic archaeological sites in central North China[J]. Boreas, 2010, 39(3): 592-602. |

| [26] |

Zhang J, Lu H, Gu W, et al. Early mixed farming of millet and rice 7800 years ago in the middle Yellow River region, China[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(12): e52146. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0052146 |

| [27] |

Wang C, Lu H, Gu W, et al. Temporal changes of mixed millet and rice agriculture in Neolithic-Bronze age Central Plain, China:Archaeobotanical evidence from the Zhuzhai site[J]. The Holocene, 2018, 28(5): 738-754. DOI:10.1177/0959683617744269 |

| [28] |

Wang C, Lu H, Gu W, et al. The spatial pattern of farming and factors influencing it during the Peiligang Culture period in the middle Yellow River valley, China[J]. Science Bulletin, 2017, 62(23): 1565-1568. DOI:10.1016/j.scib.2017.10.003 |

| [29] |

张健平, 吕厚远, 吴乃琴, 等. 关中盆地6000-2100 cal. a B.P.期间黍、粟农业的植硅体证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2010, 30(2): 287-297. Zhang Jianping, Lü Houyuan, Wu Naiqin, et al. Phytolith evidence of millet agriculture during about 6000-2100 cal. a B.P. in the Guanzhong Basin, China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2010, 30(2): 287-297. |

| [30] |

Gong Y W, Yang Y M, Ferguson D K, et al. Investigation of ancient noodles, cakes, and millet at the Subeixi Site, Xinjiang, China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2011, 38(2): 470-479. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2010.10.006 |

| [31] |

Bonnett O T. The Oat Plant:Its Histology and Development[M]. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois. Agricultural Experiment Station, 1961: 1-120.

|

| [32] |

Wynn P D, Smithson F. Opaline silka in the inflorescences of some British grasses and cereals[J]. Annual of Botany, 1966, 30(3): 525-538. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a084094 |

| [33] |

Piperno D R, Pearsall D M. Phytoliths in the reproductive structures of maize and teosinte:Implications for the study of maize evolution[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1993, 20(3): 337-362. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1993.1021 |

| [34] |

Ball T B, Gardner J S, Anderson N. Identifying inflorescence phytoliths from selected species of wheat(Triticum monococcum, T.dicoccon, T. dicoccoides, and T.aestivum)and barley(Hordeum vulgare and H.spontaneum)(Gramineae)[J]. American Journal of Botany, 1999, 86(11): 1615-1623. DOI:10.2307/2656798 |

| [35] |

Pearsall D M, Piperno D R, Dinan E H, et al. Distinguishing rice(Oryza-Sativa Poaceae)from wild Oryza species through phytolith analysis-Results of preliminary research[J]. Economic Botany, 1995, 49(2): 183-196. DOI:10.1007/BF02862923 |

| [36] |

Zhao Z J, Pearsall D M, Benfer R A, et al. Distinguishing rice(Oryza sativa Poaceae)from wild Oryza species through phytolith analysis, Ⅱ:Finalized method[J]. Economic Botany, 1998, 52(2): 134-145. DOI:10.1007/BF02861201 |

| [37] |

Jin G, Wu W, Zhang K, et al. 8000-year old rice remains from the north edge of the Shandong highlands, East China[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2014, 51: 34-42. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2013.01.007 |

| [38] |

Madella M, García-Granero J J, Out W A, et al. Microbotanical evidence of domestic cereals in Africa 7000 years ago[J]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(10): e110177. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0110177 |

| [39] |

Nasu H, Momohara A, Yasuda Y, et al. The occurrence and identification of Setaria italica(L.)P. Beauv.(foxtail millet)grains from the Chengtoushan site(ca. 5800 cal BP)in Central China, with reference to the domestication centre in Asia[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2007, 16(6): 481-494. DOI:10.1007/s00334-006-0068-4 |

| [40] |

Parry D W, Hodson M J. Silica distribution in the caryopsis and inflorescence bracts of foxtail millet[Setaria italica(L.)Beauv.]and its possible significance in Carcinogenesis[J]. Annals of Botany, 1982, 49(4): 531-540. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a086278 |

| [41] |

Zhang J P, Lu H Y, Wu N Q, et al. Phytolith analysis for differentiating between foxtail millet(Setaria italica)and green foxtail(Setaria viridis)[J]. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(5): e19726. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0019726 |

| [42] |

Weisskopf A R, Lee G A. Phytolith identification criteria for foxtail and broomcorn millets:A new approach to calculating crop ratios[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2016, 8(1): 29-42. DOI:10.1007/s12520-014-0190-7 |

| [43] |

Out W A, Madella M. Morphometric distinction between bilobate phytoliths from Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica leaves[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2016, 8(3): 505-521. DOI:10.1007/s12520-015-0235-6 |

| [44] |

Madella M, Lancelotti C, García-Granero J J. Millet microremains-An alternative approach to understand cultivation and use of critical crops in prehistory[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2016, 8(1): 17-28. DOI:10.1007/s12520-013-0130-y |

| [45] |

Ge Y, Lu H, Zhang J, et al. Phytolith analysis for the identification of barnyard millet(Echinochloa sp.)and its implications[J]. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2018, 10(1): 61-73. DOI:10.1007/s12520-016-0341-0 |

| [46] |

Twiss P C, Suess E, Smith R M. Division S-5-soil genesis, morphology, and classification(morphological classification of grasses phytolith)[J]. Soil Science Society of America, 1969, 33(1): 109-115. DOI:10.2136/sssaj1969.03615995003300010030x |

| [47] |

de Wet J M J, Oestry-Stidd L L, Cubero J I. Origins and evolution of foxtail millet(Setaria italica)[J]. Journal D'agriculture Traditionnelle et de Botanique Appliquée, 1979, 26(1): 53-64. DOI:10.3406/jatba.1979.3783 |

| [48] |

Willcox G. Measuring grain size and identifying Near Eastern cereal domestication:Evidence from the Euphrates valley[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2004, 31(2): 145-150. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2003.07.003 |

| [49] |

Harlan J R, de Wet J M J, Price E G. Comparative evolution of cereals[J]. Evolution, 1973, 27(2): 311-325. DOI:10.1111/evo.1973.27.issue-2 |

| [50] |

Fuller D Q. Contrasting patterns in crop domestication and domestication rates:Recent archaeobotanical insights from the old world[J]. Annals of Botany, 2007, 100(5): 903-924. DOI:10.1093/aob/mcm048 |

| [51] |

Pearsall D M. Paleoethnobotany:A Handbook of Procedures(second edition)[M]. San Diego: Academic Press, 2000: 1-725.

|

| [52] |

Piperno D R. Phytolith:A Comprehensive Guide for Archaeologists and Paleoecologists[M]. New York: AltaMira Press, 2006: 1-248.

|

| [53] |

Ball T, Gardner J S, Brotherson J D. Identifying phytoliths produced by the inflorescence bracts of three species of wheat(Triticum monococcum L., T.dicoccon Schrank., and T.aestivum L.)using computer-assisted image and statistical analyses[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1996, 23(4): 619-632. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1996.0058 |

| [54] |

Piperno D R, Weiss E, Holst I, et al. Processing of wild cereal grains in the upper Palaeolithic revealed by starch grain analysis[J]. Nature, 2004, 430(7000): 670-673. DOI:10.1038/nature02734 |

| [55] |

Liu L, Duncan N A, Chen X, et al. Plant domestication, cultivation, and foraging by the first farmers in early Neolithic Northeast China:Evidence from microbotanical remains[J]. The Holocene, 2015, 25(12): 1965-1978. DOI:10.1177/0959683615596830 |

| [56] |

Liu L, Bestel S, Shi J, et al. Paleolithic human exploitation of plant foods during the Last Glacial Maximum in North China[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(14): 5380-5385. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1217864110 |

| [57] |

Weiss E, Wetterstrom W, Nadel D, et al. The broad spectrum revisited:Evidence from plant remains[J]. Proceedings of National Academy Sciences of the Unite States of America, 2004, 110(26): 9551-9555. |

| [58] |

Yang X, Fuller D Q, Huan X, et al. Barnyard grasses were processed with rice around 10000 years ago[J]. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 16251. DOI:10.1038/srep16251 |

| [59] |

Chen S, Sylvia M P. Setaria P. Beauvois, Ess. Agrostogr. 51. 1812, nom. cons., not Acharius ex Michaux(1803)[M]//Flora of China Editorial Committee. Flora of China(Vol. 22). Beijing: Science Press, 2006: 531-537.

|

| [60] |

中国植物志编委会. 中国植物志(第10(1)卷)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 1990: 358. Flora of China Editorial Committee. Flora Reipublicae Popularis Sinicae (Vol.10(1))[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1990: 358. |

| [61] |

Hunt H V, Badakshi F, Romanova O, et al. Reticulate evolution in Panicum(Poaceae):The origin of tetraploid broomcorn millet, P.miliaceum[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2014, 65(12): 3165-3175. DOI:10.1093/jxb/eru161 |

| [62] |

Zohary D, Hopf M. Domestication of Plants in the Old World:The Origin and Spread of Cultivated Plants in West Asia, Europe and the Nile Valley[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000: 1-280.

|

| [63] |

王星玉. 黍稷[M]//董玉琛, 郑殿生. 中国作物及其野生近源植物: 粮食作物卷. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2006: 337-338. Wang Xingyu. Broocorn millet[M]//Dong Yuchen, Zheng Diansheng. Crops and Their Wild Relatives in China: Food Crops. Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2006: 337-338. |

| [64] |

Sakamoto S. Origin and dispersal of common millet and foxtail millet[J]. Jarq-Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly, 1987, 21(2): 84-89. |

| [65] |

Zhang J P, Lu H Y, Liu M X, et al. Phytolith analysis for differentiating between broomcorn millet(Panicum miliaceum)and its weed/feral type(Panicum ruderale)[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8: 13022. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-31467-6 |

| [66] |

Fuller D Q, Harvey E, Qin L. Presumed domestication?Evidence for wild rice cultivation and domestication in the fifth millennium BC of the lower Yangtze region[J]. Antiquity, 2007, 81(312): 316-331. DOI:10.1017/S0003598X0009520X |

| [67] |

Gegas V C, Nazari A, Griffiths S, et al. A genetic framework for grain size and shape variation in wheat[J]. Plant Cell, 2010, 22(4): 1046-1056. DOI:10.1105/tpc.110.074153 |

| [68] |

王灿, 吕厚远, 张健平, 等. 青海喇家遗址齐家文化时期黍粟农业的植硅体证据[J]. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(1): 209-217. Wang Can, Lü Houyuan, Zhang Jianping, et al. Phytolith evidence of millet agriculture in the late Neolithic archaeological site of Lajia, Northwestern China[J]. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(1): 209-217. |

| [69] |

赵志军. 青海喇家遗址尝试性浮选的结果[N]. 中国文物报, 2003-09-19(7). Zhao Zhijun. The preliminary floatation results of the Lajia site, Qinghai Province[N]. China Cultural Relics News, 2003-09-19(7). |

| [70] |

Zhao Z. New Archaeobotanic data for the study of the origins of agriculture in China[J]. Current Anthropology, 2011, 52(S4): S295-S306. DOI:10.1086/659308 |

| [71] |

吕厚远. 中国史前农业起源演化研究新方法与新进展[J]. 中国科学:地球科学, 2018, 60(2): 181-199. Lü Houyuan. New methods and progress in research on the origins and evolution of prehistoric agriculture in China[J]. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2018, 60(12): 2141-2159. |

| [72] |

Märkle T, Rösch M. Experiments on the effects of carbonization on some cultivated plant seeds[J]. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 2008, 17(1): 257-263. |

| [73] |

王灿. 中原地区早期农业-人类活动及其与气候变化关系研究[D]. 北京: 中国科学院大学博士论文, 2016: 26-27. Wang Can. Research on the Early Farming-human Activities in the Central China and Their Relation with Climate Changes[D]. Beijing: The Doctoral Dissertation of University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2016: 26-27. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/details/detail.do?_type=degree&id=Y3168488 |

2 CAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Science, Beijing 100101;

3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

4 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044;

5 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Beijing 100044)

Abstract

Phytolith analysis provides a viable method in identification of millets, especially when millet grains decayed in the archaeobotanical context. Although the diagnostic criteria used to distinguish millets and their relative wild weeds have quickly gained terrain, however, to date, the identification has still been questionable. This paper summarized the recent progress in the study of phytoliths in millet and relative wild grasses. Based on the new data, the problems and potentials of phytoliths identification of millets were further discussed as follows:(1) It is reliable to statistically identify millets and their wild relatives by phytoliths of epidermal long cells from lemma and palea, under the archaeological context. (2) By comparing the common Setaria genus of Northern China, it was found that typical ΩⅢ type is unique to S.italica and S. viridis, and the size is significantly different from the wild common Setaria genus. (3) Further explained the identification method of epidermal long cell phytoliths, typically the identifiable features and the application range of Ω/η type, and explained the key issue of statistical size. (4) Discussed the relationship between the yield of phytoliths and the yield of crops and the burial problems of phytoliths. Finally, some preliminary suggestions for deepening the morphology of millet phytoliths were put forward. It is hoped that through the summary and discussion of this paper, the phytolith analysis method can be more accurately and widely applied in the research of millet origin and spread. 2019, Vol.39

2019, Vol.39