2 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049)

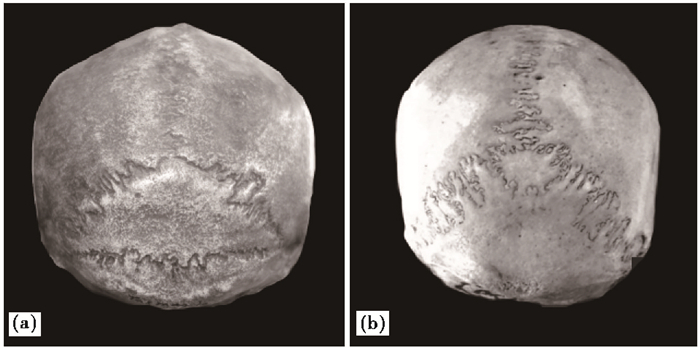

在人类头骨人字点下侧常出现两种特殊类型的缝间骨——印加骨(Inca bone,图 1a)和前顶间骨(Pre- interparietal bone,图 1b)[1],这两项性状在不同区域现代人群中的分布对于解析现代人群的扩散和分布及人群间的亲缘关系具有重要作用[2]。印加骨又名顶间骨或顶枕间骨,其形状、结构和位置变异范围较为宽泛,其中完整型印加骨是一块位于枕鳞顶间部的三角状骨片,以一条位于最上项线或枕外隆突上的横向骨缝为下界;前顶间骨则处于枕鳞顶间部顶角位置,上缘为人字缝尖,下缘常为一水平横缝,两侧边缘长度不超过人字缝的上内侧三分之一。目前,学界对印加骨和前顶间骨的鉴定标准不统一,且对两者发育机制仍存有争议[3~4]。笔者在梳理人字点周边缝间骨类型时认为,将印加骨和前顶间骨归为两种不同类型的缝间骨更为合理:印加骨是由枕骨枕鳞顶间部内各骨化中心相互间或与枕鳞枕上部愈合失败形成的;而前顶间骨可能由内侧板上核的异常愈合或额外骨化中心发育形成[5]。前顶间骨多分类型[6~8](骨块数目多达3至5个)的出现更在一定程度暗示前顶间骨起源于额外骨化中心的出现。考虑到人字点骨是由位于后卤的额外骨化中心发育形成,某些学者如Hanihara和Ishida[9]将前顶间骨和人字点骨归入同一类型进行统计。

自Dart[10]发现南方古猿头骨具有四分类型印加骨后,学者们逐渐关注印加骨在古人类头骨的表达,特别是针对中国古人类头骨展示出的多例印加骨现象提出独到的见解[11~14]。考虑到前人研究中印加骨和前顶间骨这两种缝间骨常混淆为印加骨,本文试图重新分析中国化石人类头骨中的印加骨形态特征,并对其进行鉴定分类,旨在为探寻中国古人类演化提供一些值得参考的信息。

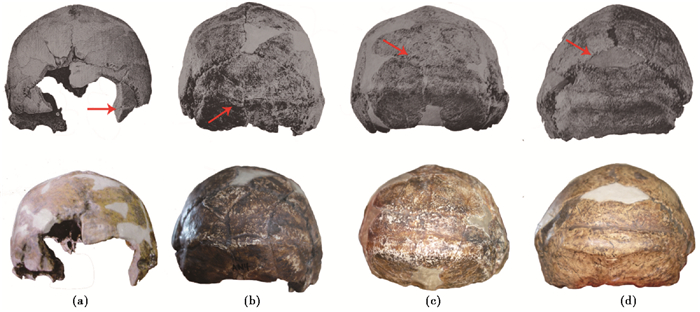

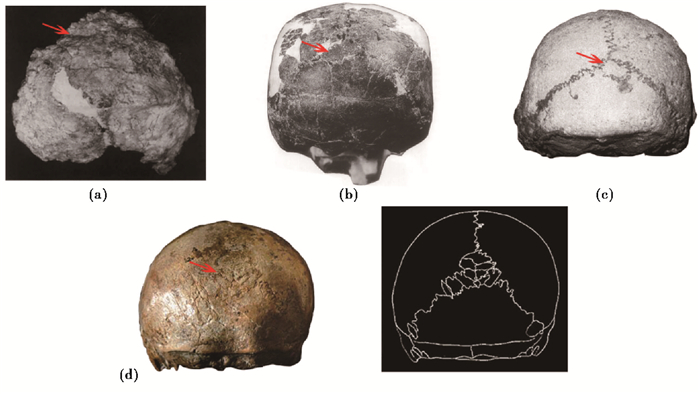

1 材料和方法本文主要选用11例中国古人类颅骨或颅骨碎片作为研究材料,含直立人4例(北京直立人2号、10号、11号和12号)(图 2),早期智人4例(大荔头骨、丁村枕骨、许家窑6号和10号顶骨)和早期现代人3例(石沟枕骨、穿洞2号头骨和丽江头骨);另外有一例国外早期现代人Olenjy Ostrow头骨(AN617),详情可见表 1。

|

图 2 北京直立人2 (a)、10 (b)、11 (c)和12 (d)号头骨背侧观 上侧图像引自Weidenreich[11],下侧图像拍摄自馆藏模型;如Weidenreich[11]所示,箭头在(a)和(b)中指向横向骨缝,在(c)和(d)中指向印加骨 Fig. 2 Posteriorview of Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅱ (a), Ⅹ (b), Ⅺ (c)and Ⅻ (d):upper image was quoted from Weidenreich[11]; lower image was photoed from the models collected in IVPP. As Weidenreich[11] stated, the arrows displayed in (a) and (b) show the mendosal suture, while the arrows displayed in (c) and (d) show the inca bone |

| 表 1 古人类研究材料 Table 1 The research materials from fossil human |

印加骨和前顶间骨主要分类标准参考杜抱朴[5]:

(1) 印加骨位于人字缝和枕骨之间,下缘常为一条横向骨缝,处于枕外隆突和上项线上方或最上项线位置可抵至两侧星点位置。印加骨可呈三角形、菱形、椭圆形、四边形或五边形等,长和宽一般大于2 cm,可见1、2或多块骨骼。

(2) 前顶间骨位于人字点后,枕鳞顶间部顶角位置,上缘为人字缝尖,下缘常为一水平横缝,两侧边缘长度不超过人字缝的上内侧三分之一,多呈三角形,由1、2或多块骨骼构成。

2 讨论 2.1 中国古人类Weidenreich[11]指出北京直立人头骨中共有4例头骨(2、10、11和12号头骨)存在印加骨。2号和10号头骨展现出一条横向骨缝(枕横缝)将枕鳞顶间部与枕骨其他区域隔开,而11号和12号头骨各展示一块占据枕鳞上半部的三角形骨块(图 2)。Weidenreich[11]在书中第25页对2号头骨进行如下描述: “2号头骨几乎缺失整块枕骨,但在枕骨右侧部位靠近星点区域仍保留一块碎片。从一条假缝的外侧缘可知,该头骨具有一条愈合横向骨缝。”(图 2a)。但是笔者未在2号头骨模型中观测到上述横向骨缝的愈合痕迹。其他学者亦对北京直立人2号头骨是否具有印加骨存于疑虑:Lahr[13]在文中转述北京直立人印加骨特征时,写到“Weidenreich(1943a)发现五例北京猿人头盖骨中有四例具有印加骨(Ⅹ,Ⅺ,Ⅻ,Ⅱ?)”,而在2号头骨后侧标注有问号;吴新智[12]指出北京猿人6具头盖骨中3具有印加骨。可即便在化石标本中展现出骨缝愈合的痕迹,也很难将其归因于印加骨的出现。

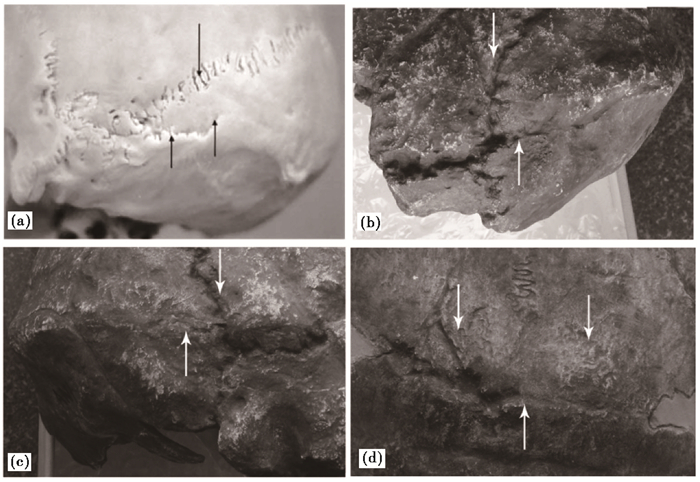

枕横缝的愈合异常会导致两种性状——假缝和印加骨的出现。假缝一般起自星点附近区域的人字缝内侧,在上项线上侧位置处向内侧走行,多为两侧对称发生[16](图 3a)。刘俊刚等[17]应用CT扫描儿童枕骨鳞部,共发现23例假缝。这些假缝自人字缝沿枕骨鳞部最上项线向内延伸至外1/ 3处,外宽内窄,两侧对称发生,常见于4个月以内的小婴儿。Mann等[18]和Antón[19]认为假缝在胎儿出生后开始愈合,约在2岁或4岁时完成愈合,但Tubbs等[16]在8例成年(> 30岁)个体头骨中观测到假缝的存在。笔者未在2号头骨左侧星点内侧区域观测到假缝或假缝的愈合痕迹,因而可以排除假缝的可能性。即便真如Weidenreich[11]所示,这例骨缝是由完整型横向骨缝(贯通两侧人字缝)愈合异常所致,那这条骨缝所在位置仍存在疑问。北京直立人头骨常发育有枕骨圆枕,呈一宽条状骨质隆起,中央部高度隆起,向外侧延伸至枕鳞的左右星点区,而Weidenreich[11]在图 2a展示这条骨缝处于枕骨圆枕区域。但在现代人中,完整型印加骨下侧缘横向骨缝处于最上项线或枕外隆突上侧。结合刘武等[20]的观点即枕骨圆枕是由上项线和最上项线融合形成,我们认为北京直立人枕横缝出现的合理位置应在枕骨圆枕上侧(如11号头骨所示),而非枕骨圆枕区域。因此,北京直立人2号头骨并不存在印加骨。

10号头骨星点内侧各存在一条长约15 mm的假缝(图 3b和3c)。一长约48.3 mm横向裂缝与左侧假缝相接,向内侧行至中线位置止于正中矢状裂隙,然后第二处横向裂缝(长27.9 mm)继续向外侧走行,却未与右侧假缝向相接(图 2b)。Weidenreich[11]认为这两处横向裂缝并非是由头骨破碎造成的,而指向横向骨缝的存在。从上文可知,若10号头骨存在枕横缝这一特征,其位置应在枕骨圆枕上方。考虑到这两处横状裂缝边缘较为整齐,笔者认为这两处横向裂缝更可能是颅骨在受地层挤压导致变形的过程中形成,而与枕横缝愈合异常无关。当头骨受地层挤压时,处于枕、项平面的枕骨转折位置处就成为应力分布较为集中的区域,而枕骨圆枕区域的骨壁厚度明显高于其他区域,因而位于枕骨圆枕稍下方区域就成为易破裂区。因此,北京直立人10号头盖骨存在真正印加骨的证据并不确凿充分。

|

图 3 假缝示意图(a,引自Tubbs等[16])、北京直立人10号头骨左侧(b)和右侧(c)假缝(下侧箭头指示假缝,上侧箭头指示人字缝)以及北京直立人11号头骨中印加骨形态(d)(下侧箭头指示枕横缝,上侧箭头指示人字缝) Fig. 3 Exampleof the mendosal suture(a, Tubbs, et al. [16]), the left(b) and right(c) mendosal sutures displayed in the Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅹ:infer arrows show the mendosal suture and superior arrow shows the lambdoidal suture. The inca bone displayed in Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅺ (d), infer arrow shows the transverse occipital suture and superior arrows show the lambdoidal sutures |

11号头骨的人字缝区域显现一例三角状缝间骨,其中左、右侧骨缝分别长约37.7 mm和42.0 mm,约占人字缝长度的一半(图 2c和3d)。这块缝间骨下缘横向骨缝距枕圆枕中点约27.1 mm,占枕骨枕平面上半部区域,所以将其归为印加骨较为恰当。在12号头骨模型人字缝尖稍后侧区域同样可见一三角状的缝间骨,左、右侧骨缝分别长约33.1 mm和28.8 mm,约占人字缝长的1/ 3(图 2d)。下侧骨缝至枕骨圆枕中央位置约32.7 mm,明显超出枕鳞上部中线位置,将其归入该前顶间骨更为合适。但令笔者感到困惑的是,12号头骨模型中该缝间骨与枕骨相接的下侧骨缝边缘较为光滑。此外,Thoma[21]同样将北京直立人12号头骨中人字缝尖下的缝间骨归入前顶间骨,而非印加骨。

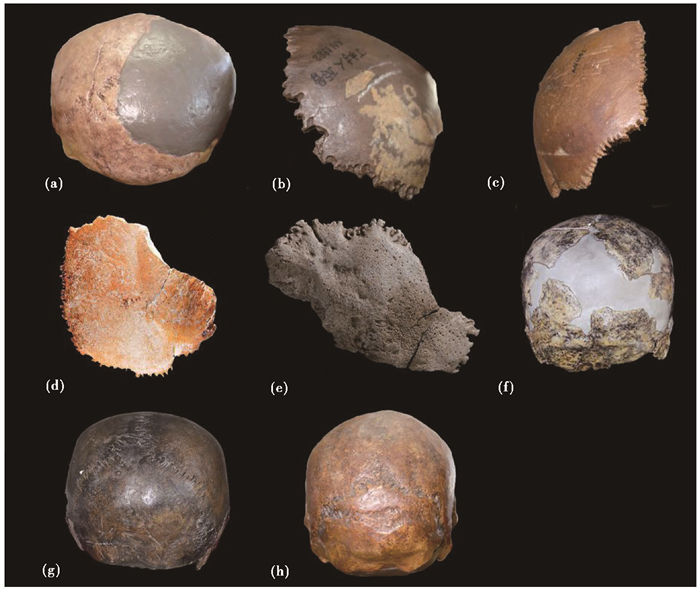

大荔古人类头骨的枕鳞右上部缺失,但在左上部区域存留一块缝间骨残片,高度和宽度约20.0 mm[22],下侧横向骨缝长约20.2 mm(图 4a)。笔者认为大荔缝间骨下缘明显高于枕鳞上部中线位置,暗示存在前顶间骨而非印加骨。1976年发现丁村幼儿顶骨后上部即人字缝和矢状缝转角位置处似乎缺失一角,但顶骨后缘和上缘的锯齿保持完(图 4b)。吴新智[23]提出丁村古人类可能存在三角型印加骨,但刘武等[15]在描述丁村顶骨时将印加骨这一术语调整为顶枕缝间骨。结合丁村标本属于幼儿个体,笔者认为丁村顶骨中的人字缝和矢状缝形态很难提供指向性信息表明该顶骨所属个体拥有印加骨,这可能是骨缝正常形态或尺寸较小的顶枕缝间骨或前顶间骨。同一现象亦见于许家窑地点的6号(图 4c)和10号顶骨(图 4d)。吴新智[23]提及这两件顶骨后上角有天然缺刻,且10号顶骨缺刻范围大于6号顶骨,这很可能暗示许家窑早期智人具有印加骨这项性状。据笔者观察近20例印加骨馆藏标本和广泛阅读文献后,发现典型或者其他类型的印加骨出现并不会伴随顶骨后上角的缺刻,当然不排除这是由笔者观察标本较少所致。但从发育机制的角度来看,印加骨是由枕骨内部骨化中心的愈合异常所致[3~4],这意味着印加骨与顶骨相接处的人字缝应保持常见形态。因此,将人字缝和矢状缝连接区域的这种顶骨特殊形态与印加骨联系起来似乎并不恰当,更可能归因于额外骨外中心的出现(人字点骨或前顶间骨)影响了人字缝尖区域的骨缝形态。整体而言,丁村和许家窑地点的顶骨化石形态并不能提供强有力的证据支持这3件顶骨标本所属个体具有印加骨,下缘横向骨缝才是提示印加骨或前顶间骨是否存在的关键性特征。

|

图 4 大荔头骨(a)、丁村顶骨(b)、许家窑Ⅵ顶骨(c)、许家窑Ⅹ顶骨(d)、石沟枕骨(e)、穿洞2号头骨(f)[15]、丽江头骨(g)和Olenjy Ostrow头骨(h) Fig. 4 Viewof Dali skull (a), Dingcun parietal bone (b), Xujiayao Ⅵ parietal bone (c), Xujiayao Ⅹ parietal bone (d), Shigou occipital bone (e), Chuangdong Ⅱ skull (f)[15], Lijiang skull(g) and Olenjy Ostrow skull (h) |

石沟枕骨上缘是一条长约52.0 mm的横向骨缝,从左侧向右侧轻微斜向下走行(图 4e)。笔者基于以下两项特征,认为石沟枕骨所属个体可能伴有一完整型印加骨:1)横向骨缝下紧邻最上项线;2)枕骨右下侧残留的枕乳缝意味该横向骨缝与星点区域相接近。穿洞古人类2号头骨中左侧枕鳞上部残留一段横向骨缝,这段骨缝所处位置明显高于人字点和枕骨圆枕间的中线位置,表明穿洞2号头骨可能具有前顶间骨(图 4f)。丽江古人类头骨[24]在人字缝尖区域存在一近似倒三角状的缝间骨,长约33.5 mm,高约30.7 mm(图 4g)。鉴于这一缝间骨对两侧顶骨和枕骨顶部形态均有影响,将其归为人字点骨更为合适。

此外,笔者在观察中国科学院古脊椎动物和古人类研究所馆藏人类头骨标本和模型时,发现Olenjy Ostrow(AN617)头骨模型(图 4h)的枕骨枕鳞区展示出一特殊形态的骨缝结构。这条骨缝长约47.5 mm,呈水平走行,但该骨缝未能贯穿枕骨鳞部仅与左侧人字缝相接。虽然这例骨缝位于人字缝尖和枕外隆突间的中线位置,但鉴于其未将枕骨顶间部与其他部分完全分隔开,表明这一头骨并未存在印加骨,而为单一完整的枕骨。由此可见,即便在某一头骨枕鳞中部显示出横向骨缝,但若这一骨缝结构未能保存完整,我们仍需慎重考虑这件标本所属个体是否具有印加骨。

国外古人类头骨亦显示多例前顶间骨或印加骨(图 5)。目前,国外研究中报道3例头骨具有前顶间骨:Thoma[21]指出Vértesszöllös枕骨鳞部上侧出现一横向骨缝,将一三角形骨块与枕骨相隔;Ndutu头骨人字缝尖下侧可见一不对称三角形缝间骨[22];希腊佩特拉罗纳Clemontsi洞穴中的Petralona头骨人字缝尖下侧可见一近似矩形的缝间骨[23]。Boaz和Howell[25]报道一例古人类头骨L.894-1中的lt残片中可见三处骨缝汇聚在一起,但这一区域并非是星点区,结合骨片的平坦程度表明这件骨块是由枕骨枕鳞和右侧顶骨组成。从头骨lt碎片中的横向骨缝可推断L.894-1头骨可能具有假缝或印加骨。Mizoguchi[26]在提及澳大利亚东南部的Keilor头骨时,写道“值得注意的是这例头骨具有尺寸较大的印加骨,以至于人字点的位置都不能够精确定位(Brown,2009)”;Hanihara和Ishida[27]在文中提及De Villiers发现在南非早期现代人头骨展现出印加骨。此外,尽管Bae[14]认为Saccapastore头骨具有印加骨,但从图 5d不难看出这例头骨在人字点附近展示出多块顶枕缝间骨,且对两侧顶骨和枕骨形态均有扰动,因此不宜归入印加骨。笔者认为即便印加骨和部分前顶间骨的发育机制相同——由枕骨鳞部骨化中心愈合异常所致,两者可归为同一类型骨骼,且不考虑古人类是否为生存在某一固定区域内的同一族群,仍难看出中国古人类(直立人和早期智人)个体拥有印加骨的频率高于国外古人类。

|

图 5 Vértesszöllös枕骨(a)[28]、Ndutu头骨(b)[29]、Petralona头骨(c)[30]和Saccapastore头骨(d)[31] Fig. 5 Posteriorview of the Vértesszöllös occipital bone (a)[28], Ndutu skull (b)[29], Petralona skull (c)[30] and Saccapastore skull (d)[31] |

在多地区连续进化及附带杂交假说中[32],印加骨常作为一项重要的连续性性状,用以支持中国更新世古人类间存在一定的亲缘关系。但前人关于中国古人类印加骨的研究均较简略,缺少具体的形态描述与鉴定分类标准,这为后续对比研究带来一定的困惑。本文对相关古人类头骨化石开展更为细致的研究后,发现北京直立人11号头骨和石沟枕骨所属个体拥有印加骨,而北京直立人12号头骨、大荔头骨和穿洞2号头骨具有前顶间骨。北京直立人2号中骨缝愈合痕迹和10号头骨中的横向骨缝并非是枕横缝,可能是与地质埋藏相关,表明这两例头骨并不存在印加骨。丁村和许家窑地点的3例顶骨化石展现出的后上角缺刻特征,应与额外骨化中心的出现密切相关而非由枕骨骨化中心的愈合异常所致,因而将其与印加骨相联系并不恰当。故此,本文认为中国更新世古人类印加骨的出现频率并不高。

值得注意的是,当骨缝保留极少或者并不完整时,我们仍需谨慎考虑标本所属个体是否真的具有印加骨或前顶间骨。希望更多古人类化石标本的出现及枕骨和印加骨发育机制的深入探索,为印加骨形态和发生频率的研究提供更有力的证据,这对了解中国古人类的体质特征以及演化道路具有重要意义。

致谢: 感谢中国科学院古脊椎动物与古人类研究所标本室马宁老师在观摩模型和标本给予的热情帮助;感谢刘文辉同学在模型拍照中给予的帮助。

| [1] |

Bhanu P S, Sankar K D. Interparietal and pre-interparietal bones in the population of south coastal Andhra Pradesh, India[J]. Folia Morphologica, 2011, 70(3): 185-190. |

| [2] |

Carolineberry A, Berry R J. Epigenetic variation in the human cranium[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1967, 101(Pt2): 361-379. |

| [3] |

Srivastava H C. Ossification of the membranous portion of the squamous part of the occipital bone in man[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1992, 180(Pt2): 219-224. |

| [4] |

Matsumura G, Uchiumi T, Kida K, et al. Developmental studies on the interparietal part of the human occipital squama[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1993, 182(Pt2): 197-204. |

| [5] |

杜抱朴. 人字点骨、印加骨和前顶间骨鉴定分类辨析[J]. 现代人类学, 2017, 5(4): 47-53. Du Baopu. Discriminate analysis of the ossicle at lambda, inca bone and pre-interparietal bone[J]. Modern Anthropology, 2017, 5(4): 47-53. |

| [6] |

Saxena S K, Chowdhary D S, Jain S P. Interparietal bones in Nigerian skulls[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1986, 144: 235-237. |

| [7] |

Gopinathan K. A rare anomaly of 5 ossicles in the pre-interparietal part of the squamous occipital bone in North Indians[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 1992, 180(Pt1): 201-202. |

| [8] |

赖育鹏, 贺伦, 孙建永. 颅骨顶间骨变异一例[J]. 解剖学杂志, 2017, 40(2): 180. Lai Yupeng, He Lun, Sun Jianyong. One case for the interparietal bone variation[J]. Chinese Journal of Anatomy, 2017, 40(2): 180. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-1633.2017.02.039 |

| [9] |

Hanihara T, Ishida H. Frequency variations of discrete cranial traits in major human populations. Ⅰ. Supernumerary ossicle variations[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 2001, 198(Pt6): 689-706. |

| [10] |

Dart R A. The Makapansgat protohuman Australopithecus prometheus[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1948, 6(3): 259-284. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8644 |

| [11] |

Weidenreich F. The skull of Sinanthropus pekinensis:A comparative study of a primitive hominid skull[J]. Palaeontologia Sinica, 1943, New Series D(10): 1-486. |

| [12] |

吴新智. 中国远古人类的进化[J]. 人类学学报, 1990, 9(4): 312-321. Wu Xinzhi. The evolution of humankind in China[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 1990, 9(4): 312-321. |

| [13] |

Lahr M M. The multiregional model of modern human origins:A reassessment of its morphological basis[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1994, 26(1): 23-56. DOI:10.1006/jhev.1994.1003 |

| [14] |

Bae C J. The late Middle Pleistocene hominin fossil record of eastern Asia:Synthesis and review[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 2010, 143(S51): 75-93. DOI:10.1002/ajpa.v143:51+ |

| [15] |

刘武, 吴秀杰, 邢松, 等. 中国古人类化石[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2014: 312. Liu Wu, Wu Xiujie, Xing Song, et al. Human Fossils in China[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2014: 312. |

| [16] |

Tubbs R S, Salter E G, Oakes W J. Does the mendosal suture exist in the adult?[J]. Clinical Anatomy, 2007, 20(2): 124-125. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1098-2353 |

| [17] |

刘俊刚, 李欣, 王春祥, 等. 儿童枕骨鳞部正常解剖, 解剖变异及骨折的三维CT特征[J]. 中华放射学杂志, 2013, 47(4): 361-363. Liu Jungang, Li Xin, Wang Chunxiang, et al. Three-dimensional CT features of occipital squama normal anatomy, anatomic variations and fractures[J]. Chinese Journal of Radiology, 2013, 47(4): 361-363. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1005-1201.2013.04.016 |

| [18] |

Mann K S, Chan K H, Yue C P. Skull fractures in children:Their assessment in relation to developmental skull changes and acute intracranial hematomas[J]. Child's Nervous System, 1986, 2(5): 258-261. |

| [19] |

Antón S C. Developmental age and taxonomic affinity of the Mojokerto child, Java, Indonesia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1997, 102(4): 497-514. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8644 |

| [20] |

刘武, Mbua E, 吴秀杰, 等. 中国与非洲近代-现代人类某些颅骨特征的对比及其意义[J]. 人类学学报, 2003, 22(2): 89-104. Liu Wu, Mbua E, Wu Xiujie, et al. The comparison of cranial features between Chinese and African Holocene humans, and their implications[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2003, 22(2): 89-104. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3193.2003.02.001 |

| [21] |

Thoma A. Some notes on Wolpoff's notes on the Vértesszølløs occipital[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1978, 7(4): 323-324. DOI:10.1016/S0047-2484(78)80073-6 |

| [22] |

吴新智. 大荔颅骨在人类进化中的位置[J]. 人类学学报, 2014, 33(4): 405-426. Wu Xinzhi. The place of Dali cranium in human evolution[J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2014, 33(4): 405-426. |

| [23] |

吴新智.中国的早期智人[M] //吴汝康, 吴新智, 张森水.中国远古人类.北京: 科学出版社, 1989: 24-41. Wu Xinzhi. Early Homo sapiens from China[M] // Wu Rukang, Wu Xinzhi, Zhang Senshui. Early Humankind in China. Beijing: Science Press, 1989: 24-41. |

| [24] |

云南省博物馆. 云南丽江人类头骨的初步研究[J]. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1977, 15(2): 157-161. Yunnan Provincial Museum. Preliminary study on the human cranium from Lijiang, Yunnan[J]. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 1977, 15(2): 157-161. |

| [25] |

Boaz N T, Howell Clark F. A gracile hominid cranium from upper member G of the Shungura formation, Ethiopia[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1977, 46(1): 93-108. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8644 |

| [26] |

Mizoguchi Y. Typicality probabilities of Late Pleistocene human fossils from East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Australia:Implications for the Jomon population in Japan[J]. Anthropological Science, 2011, 119(2): 99-111. DOI:10.1537/ase.090330 |

| [27] |

Hanihara T, Ishida H. Os incae:Variation in frequency in major human population groups[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 2001, 198(2): 137-152. DOI:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19820137.x |

| [28] |

Wolpoff M H. Some notes on the Vértesszølløs occipital[J]. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 1977, 47(3): 357-363. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1096-8644 |

| [29] |

Clarke R J. The Ndutu cranium and the origin of Homo sapiens[J]. Journal of Human Evolution, 1990, 19(6): 699-736. |

| [30] |

Stringer C B, Howell F C, Melentis J K. The significance of the fossil hominid skull from Petralona, Greece[J]. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1979, 6(3): 235-253. DOI:10.1016/0305-4403(79)90002-5 |

| [31] |

Di Ieva A, Bruner E, Davidson J, et al. Cranial sutures:A multidisciplinary review[J]. Child's Nervous System, 2013, 29(6): 893-905. DOI:10.1007/s00381-013-2061-4 |

| [32] |

Wolpoff M H, Wu X Z, Thorne A G. Modern Homo sapiens origins: A general theory of hominid evolution involving the fossil evidence from East Asia[M]//Smith F H, Spencer F. The Origins of Modern Humans: A World Survey of the Fossil Evidence. New York: Alan R. Liss, 1984: 411-483.

|

2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049)

Abstract

The inca bones, an important discrete trait, is pivotal to exploring the origin, diffusion and distribution of modern humans. However, another suture bone known as pre-interparietal bone is also located in the interparietal region of the occipital bone, which results in a confusion with the inca bone in previous studies. Therefore, we aimed to take a detailed description of the inca bones appeared in the Chinese hominin fossils and if possible, to make a reasonable identification and classification. We used 11 specimens mainly from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology and Folk Custom Museum of Dingcun for this study. It contains 4 Homo erectus skulls (Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅱ, Ⅹ, Ⅺ and Ⅻ), 4 early Homo sapiens specimens (Dali skull, Dingcun parietal bone, Xujiayao Ⅵ and Ⅹ parietal bones)and 3 early modern human specimens (Shigou occipital bone, Chuangdong Ⅱ skull and Lijiang skull).In Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅺ, an accessory transverse suture separates the superior part of the occipital planum form remainder, which forms a large triangular bone. The transverse suture in Shigou fossil is approximately 52.0 mm at the superior border of the occipital squama just above the highest nuchal line. Considering location and size of the transverse suture, these two individuals display the inca bones.Weidenreich[11] (1943)stated that Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅱ preserves a fused mendosal suture presented on the medial side of the asterion region, while Homo erectus pekinensis Skull Ⅹ displays an accessory transverse suture which entirely or partly separates a genuine inca bone with the remaining bone. The mendosal suture refers to an accessory suture of the occipital bone originated from the asterion region, which usually runs horizontally just above the superior nuchal line. If we accepted the view that the occipital torus can develop into the superior and highest nuchal lines, combined with the position of transverse suture, it seems that the inca bones cannot appear in the Skull Ⅱ and Skull Ⅹ.In Homo erectus pekinensis Ⅻ, Dali and Chuangdong Ⅱ skulls, we found the sutural bones donot beyond the medial one-third of the lambdoid suture, and the inferior margins are significantly above the highest nuchal line. Thus, these three bones can be classified as pre-interparietal bone. The missed posterosuperior portion showed in Dingcun and Xujiayao parietal bones, which may be related to the ossicle at lambda or pre-interparietal bone, is affected by the appearance of extra ossification centers that disturbs the parietal development. In addition, Lijiang skull displays an ossicle at lambda.In sum, it seems that the inca bone just appears in the Homo erectus pekinensis Ⅺ skull and Shigou hominin. 2018, Vol.38

2018, Vol.38