2 中国科学院青藏高原地球科学卓越创新中心, 北京 100101;

3 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049)

我国黄土高原黄土-红粘土季风演化研究在国际上产生了广泛深远的影响,恢复了约7~8 Ma以来东亚季风时空演化的详细过程,实现了与全球海洋和冰芯记录的精细对比,提出了季风演化的驱动机制和假说,对过去全球变化研究做出了重要贡献[1~7]。然而当我们将研究延伸至晚新生代甚至整个新生代气候环境变化时,就遇到了许多风尘堆积气候变化研究时无需考虑或者没有引起重视的问题(除了年代问题难以解决外),即记录气候环境变化的盆地地层往往是受控于构造和气候的双重影响,沉积地层体和沉积相在时间和空间上会因盆地的性质和构造活动产生显著的变化,气候变化仅叠加其上,即使有风尘物质从外域携带加入,也只能叠加在这个过程之上。换言之,对于盆地地层发育和沉积相变化而言,构造作用是控制盆地性质和演化最核心的因素,而沉积相变化成为所有地层气候环境变化记录(包括所有物理化学代用指标记录)中第一级的控制因素。因此,对沉积相时空变化的准确了解成为我们正确解释地层气候环境代用指标记录不可逾越的第一步,也是最重要的一步。为此,就必须首先了解控制沉积相时空发育的构造活动和盆地性质与演化历史。

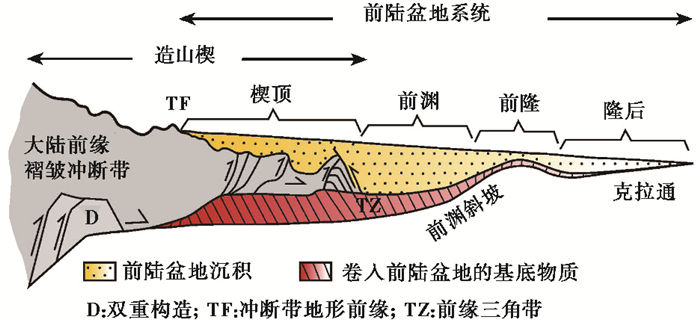

青藏高原周边和许多内陆山前普遍发育挠曲盆地或称陆内再生前陆盆地[8],它们在构造上的演化已经得到了大量深入的研究,尤其在油气勘探中得到广泛的应用[8~10]。经典的前陆盆地是指大陆碰撞中与俯冲洋壳相连的一个大陆的前缘(前陆部分),由于碰撞时被另一个大陆加载其上,导致大陆前缘部分在重力作用下被挠曲下沉,形成前渊,而远离前渊的另一侧则像跷跷板一样反弹翘起,形成前隆,前隆之后的广大克拉通大陆地区,会形成广泛宽浅的隆后盆地[11~12](图 1)。随着碰撞的进行,加载的大陆前缘不断向另一侧大陆推进,导致加载大陆前缘不断破裂,形成显著的向前渊发展的造山楔和冲断褶皱带,其上靠前部分也可以接受部分来自山地的沉积物质,成为所谓的楔顶[13](图 1)。发育于前陆盆地中的沉积物严格受到碰撞进程控制的前陆盆地构造演化的控制,碰撞早期加载的造山楔由于位于海平面之下,造山楔的侵蚀和提供的物源都有限,形成欠补偿性沉积,导致沉积物薄,沉积速率低,沉积物多为半深海-浅海相的细粒页岩、灰岩、泥岩、粉砂岩和砂岩的旋回,称为复理石沉积阶段;碰撞晚期加载的造山楔露出海平面,造山楔的侵蚀和提供的物源急剧增加,形成过补偿性沉积,导致沉积物厚,沉积速率高,沉积物多为陆相粗粒砂岩和砾岩,称为磨拉石沉积阶段,并对早期复理石阶段沉积物产生显著的冲断褶皱变形和抬升改造[11~12]。

|

图 1 前陆盆地构造特征(修改自文献[13]) Fang等[14]提议和加入“前渊斜坡”带,它有利于精细刻画陆内再生前陆盆地沉积相体系的特征和时空演化 Fig. 1 Tectonic units of a foreland basin system, modified from reference [13]. TF:Topographic front of the thrust belt; Diagonally ruled area:indicates pre-existing miogeoclinal strata; D:Duplex; TZ:Frontal triangle zone. For an intracontinental regenerated foreland basin or flexural basin, Fang et al.[14] propose to add a new unit of foredeep slope to depict better the distribution and temporospatial evolution of sedimentary facies system of the basin |

陆内再生前陆盆地或挠曲盆地与经典的前陆盆地构造变形历史非常相似,仅仅是构造分布部位不是大陆碰撞的前缘,而是陆内古老的盆山结合部位,它们过去往往也是大陆碰撞的前缘部位,但是碰撞后已经成为大陆的一部分,在新的大陆碰撞过程中,该处薄弱的深大断裂再次被激发活动,导致山体沿深大断裂向盆地内冲压,盆地边缘地壳受压挠曲变形拗陷,形成所谓的再生前陆盆地[8]或挠曲盆地。其构造演化特点也是随变形前锋的来临早期冲断较慢,晚期较快,并形成显著的多排冲断褶皱体系,盆地边缘基底和早期沉积物质均被卷入其中,对油气的形成、运移和保存产生深刻影响[8~10]。

但是挠曲盆地的构造演化如何从时空上控制地层沉积相的发育,并与气候变化相互作用,进而控制气候环境变化记录的研究,目前鲜有涉及。本文列举有精细年代学控制和沉积学研究的临夏盆地[14~17]为例,构建出一个共性模型,来解读和构建这类盆地构造演化如何在时空上控制地层和沉积相演化,进而控制地层的气候环境记录[14]。不仅如此,盆地沉积体和沉积相的时空变化还深刻地影响了同一盆地地层的对比,包括所谓标志层的对比常常导致误判和误对比。我国西北目前许多盆地诸如寺口子盆地[18~20]、天水盆地[21~24]、兰州盆地[25~29]、临夏盆地[16~17, 30~34]、西宁盆地[35~42]、肃北盆地[43~44]、塔里木盆地[45~53]、准噶尔盆地[50, 54~58]等存在的地层年代控制对比争论和古气候记录相互矛盾的现象,可能都归因于此。

1 地质地理背景临夏盆地在区域地理上属于季风边缘区半湿润气候向半干旱气候的过渡区,盆地平均海拔2000 m,年平均气温6.3~8.0 ℃,年降雨量487.9 mm(北部为415.5 mm,南部为563.3 mm),地貌上属于黄土高原的西南隅。

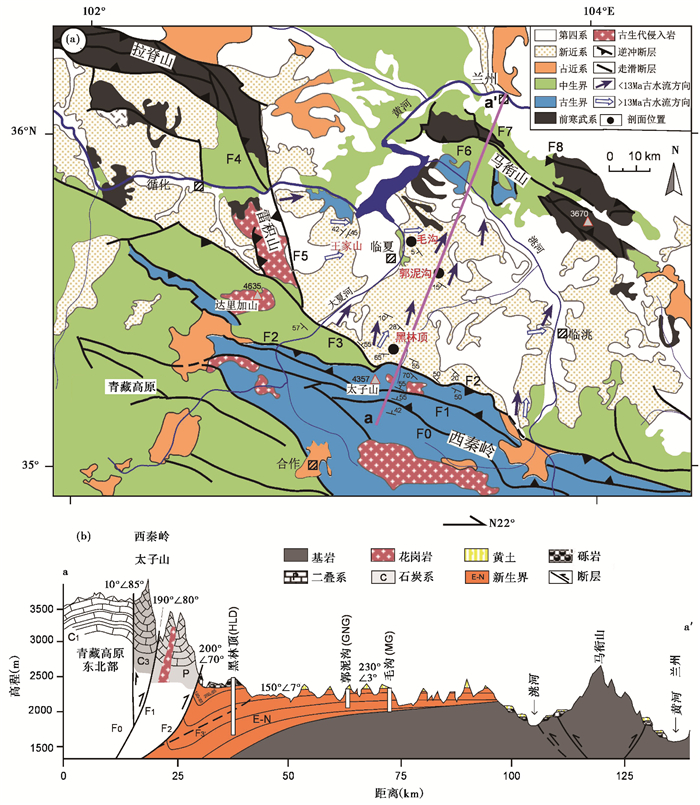

在地质构造上临夏盆地属于青藏高原东北部边缘陇中盆地西南隅的一个次级盆地。陇中盆地是由西面祁连山余脉、北面海源走滑断裂、东面六盘山断裂和南面北秦岭断裂及其山脉围限的一个大型山间盆地,其基底主要是祁连山脉的古生代和中生代地层,向西面基底逐步显露地表成山,与祁连山东延余脉相接,分割盆地西部边缘,形成一系列次级盆地,如永登盆地、西宁盆地、兰州盆地和临夏盆地[17]。临夏盆地西、南和北边界分别为青藏高原东北缘的雷积山、西秦岭和祁连山东延余脉马衔山,东面与陇中盆地主体相连通(图 2)。盆地内堆积新生代地层,地层在盆地中部和北部较薄,约300~500 m,厚度向西和南侧的山前显著增厚至1600 m以上,属典型的山前挠曲盆地[14, 16]。盆地内发现了30多处多达十几个层位的哺乳动物化石点,出产了数万件化石,是全球新生代化石最全和最多的盆地之一[18, 30~33, 59~61],国家在此建立了两个大型古哺乳动物化石博物馆和一个大型古动物化石埋藏原址馆。经过二十多年的努力,我们在临夏盆地不同部位开展了系统的古地磁年代测定,重新划分和建立了新的地层序列,开展了详细的盆地构造演化、沉积相和气候环境变化研究。目前盆地发现的最老哺乳动物化石年代为渐新世,测得的最老地层年代为约29 Ma,盆地洪积-河湖相地层最晚约1.8 Ma结束,此后开始了全盆的黄河水系阶地的发育和典型第四纪风成黄土的堆积[14~17]。

|

图 2 临夏盆地构造地质简图和研究剖面位置(a)及其横剖面图(b) 修改自文献[14] Fig. 2 Geological map of the Linxia Basin and locations of the studied sections (a) and their geological cross section (b), modified from reference [14] |

本文研究选用的毛沟(35.67°N,103.32°E)、郭泥沟(35.55°N,103.42°E)和黑林顶(35.38°N,103.32°E) 3个剖面分别来自临夏盆地南北断面上3个不同部位(图 2),它们均有精细的年代控制[14~16, 62]。

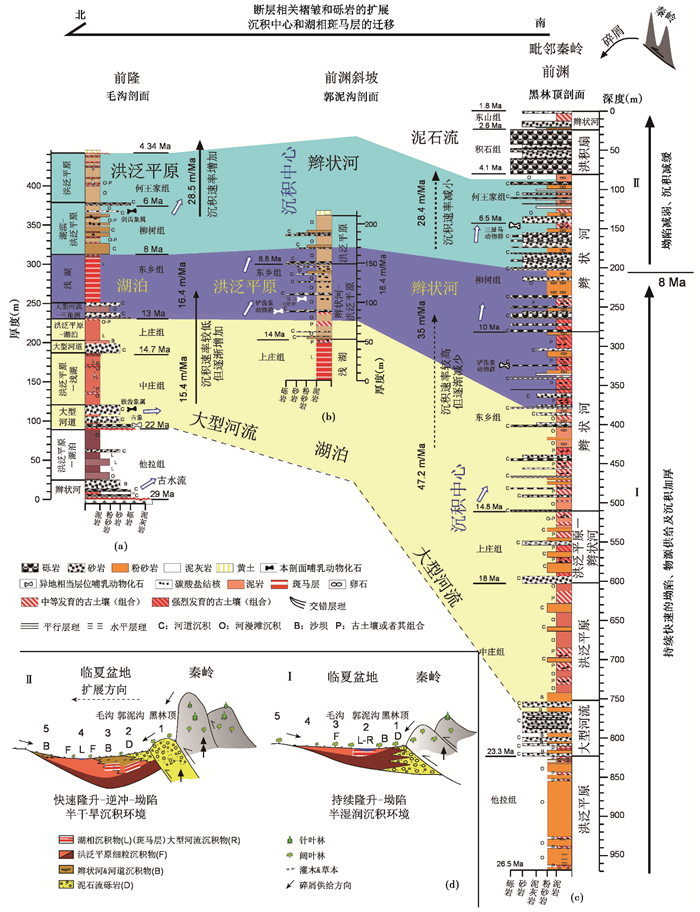

以临夏盆地中央的毛沟剖面(MG)为例,地层序列从下往上可以简单概括为6个组,对应6个正粒序沉积旋回[14~17](图 3a),分别是:1)渐新世他拉组,年代约29.0~21.9 Ma,厚91 m,下部为辫状河紫红-深褐红色分选差的块状砂质细砾岩、具交错层理的砾质粗砂岩和块状细砾质含膏泥岩;中部为湖相紫红色水平层理发育的粉砂岩和泥岩互层;上部为洪泛平原紫红色块状泥岩[14, 16](图 3a)。2)早中新世中庄组,年代21.4~14.7 Ma,厚67 m,底部为特征的厚层、发育大型槽状、板状交错层理或平行层理的锈黄色含砾粗砂岩,夹互层状粉砂岩和泥岩和次生脉状石膏,属大型河道沉积;中上部为韵律层状、块状(偶尔水平层理)褐红色、浅褐红色泥岩,含团块状、透镜状、脉状石膏和几层古土壤,属洪泛平原及其上的小型浅湖沉积[14, 63]。3)中中新世上庄组,为一套河湖相沉积,年代14.7~13.1 Ma,厚45 m,底部为一层青灰色平行层理发育的中粒砂岩(河流相),其上为褐红色水平层理粉砂岩及薄层粉砂岩与泥岩韵律互层(湖相),上段为褐红色粉砂岩与泥岩互层及块状泥岩(河湖相)。4)晚中新世早期东乡组,为一套特征醒目的以震荡湖相为主的沉积,年代13.1~7.8 Ma,厚84 m,下段(24 m)为青灰色具正粒序的砂质细砾岩(河道沉积)、褐红色、青灰色、含锈斑的块状、水平纹层状粉砂岩和泥岩(河湖相);上段(60 m)为特征的韵律层状紫红色块状泥岩(厚约1~2 m)与块状或水平层理青灰-灰白色泥灰岩(厚约0.5~1.0 m)互层,因红白相间酷似斑马条纹而形象的被称为斑马层[15, 17],属典型的由相对干湿波动形成的震荡型浅湖相沉积[14, 63]。5)晚中新世晚期柳树组,为一套浅湖向洪泛平原过渡的沉积,年代7.8~6.0 Ma,厚53 m,下段为褐黄色块状泥岩夹数条青灰色泥灰岩条带和少量薄层砂岩(滨浅湖相),上段为5个大的粒序状褐黄、锈黄色块状粉砂岩和泥岩,夹少量薄层细砂岩,含多层褐色古土壤和大量直径2~10 cm钙结核,属洪泛平原沉积[14, 63]。6)以早上新世为主的何王家组,为一套典型洪泛平原沉积,但有明显的风成粉尘加入,年代为6.0~4.3 Ma,厚60 m,下段为呈透镜状分布的灰色钙质胶结、有叠瓦构造的砂质细砾岩(河道沉积);上段为褐黄色块状粉砂岩和泥岩,夹多层浅褐红色古土壤及其细小钙结核,含少许次生石膏脉,视为有明显黄土加入的洪泛平原堆积[14](图 3a)。

|

图 3 临夏盆地中央至南缘毛沟(a)、郭泥沟(b)和黑林顶(c)剖面地层和沉积相对比及其所反映的盆地沉积构造演化(d)(修改自文献[14, 62]) (a)、(b)和(c)中的黄、蓝和灰蓝色区域为以22 Ma、13 Ma、8 Ma和4.34 Ma为边界的等时区域,在演化阶段Ⅰ和Ⅱ揭示的前渊和前隆区沉积速率,随前渊和盆地中心(湖泊所在)以及洪积扇-辫状河沉积相体系向盆内迁移和扩展而产生的同时分别减小和增加的趋势;(d)盆地沉积构造演化过程的卡通图 Fig. 3 Correlation of the stratigraphy vs. sedimentary facies of the three studied sections (a~c) in the Linxia Basin and their indicated basin tectonosedimentary evolution (d), modified from references [14, 62]. Note that the generally decreasing and increasing trends of sedimentation rates in the foredeep and forebulge zones concur with basinward migrations of the foredeep and basin center (lake) and their accompanying expansions of alluvial fan-braided river within same time intervals (22 Ma, 13 Ma, 8 Ma and 4.34 Ma) in Phases Ⅰ and Ⅱ. A cartoon presentation of processes in Phases Ⅰ and Ⅱ is presented in lower left for easy tracing in (d) |

整个地层序列除了他拉组与下伏盆地基底花岗岩为不整合接触、与上覆中庄组地层为假整合接触,以及顶部何王家组地层与上覆薄层黄土为不整合接触外,其余地层组之间均为整合接触。在盆地中央最高点东山顶-王家山一带,何王家组之上不整合覆盖一套巨厚分选较差的洪积扇砾岩层——积石组砾岩,时代约3.6~2.6 Ma,厚60 m,其上假整合一套灰绿、灰黑和灰黄色湖沼相泥炭粉砂岩和水下黄土组合——东山组,时代约2.5~1.8 Ma,厚77 m,其中产真马(Equus sanmeniensis)、猞猁(Lynx sp.)和羚羊(Gazella sp.)化石[30]。其后黄河支流大夏河系列阶地砾石层和其上典型黄土发育时期开始[15, 17, 64]。

郭泥沟剖面(GNG)位于毛沟剖面东南面约11 km处(图 2),测量剖面出露厚度211 m,在高度88 m和100 m处分别产出中中新世铲齿象动物群和晚中新世三趾马动物群,其中三趾马为本区也是中国最老的晚中新世初期的东乡三趾马[30],古地磁测年确定东乡三趾马年代为11.5 Ma,而整个出露剖面形成于约> 17.3~ < 7.7 Ma[14](图 3b)。该剖面底部(0~56 m,> 17.3~14 Ma)出露特征的斑马层紫红色泥岩夹白色泥灰岩条带的浅湖相沉积(上庄组)(未见底)。其上(56~148 m,即14.0~8.8 Ma)整合出现多个旋回的灰黄色细砾岩、砂岩(小型河道沉积)和褐黄色块状粉砂岩、泥岩,含几层褐红色古土壤及其钙结核层(洪泛平原沉积),视为东乡组;其后148~211 m(8.8~ < 7.7 Ma)开始另一个大的洪泛平原沉积旋回,即柳树组灰黄、浅褐黄色砂质砾岩和粉砂岩、泥岩组合,含多层钙结核层,剖面顶部被侵蚀,为厚层老黄土不整合所覆盖(图 3b)。

黑林顶剖面(HLD)距郭泥沟剖面约25 km,靠近南部西秦岭山前(图 2),剖面由顶部浅钻HZT(129.2 m)、中部天然剖面HLD(226.5 m)和底部深钻HZ1-HZ2(共611.45 m)三部分组成,总厚度967.15 m,深度143 m和322 m处发现大量化石,分属于晚中新世晚期三趾马动物群和初期铲齿象动物群[30],从下往上依据岩性变化、哺乳动物化石和古地磁精确测年,可以明显划分出可与毛沟剖面地层对比的8个组,整体呈现为一个明显向上变粗的旋回(图 3c):1)渐新世他拉组,厚度大于144.15 m(深度967.15~823.00 m,未见底),年代 > 26.5~23.3 Ma,主要为褐红色粉砂岩和浅紫红色泥岩的韵律互层,其中夹多层深褐红色古土壤及其钙结核层,属典型的洪泛平原沉积[62]。2)早中新世中庄组,厚223 m(深度823~602 m),年代23.3~18.0 Ma,明显可分为上下两段:下段(深度823~752 m)为褐色厚层具弱平行层理的细砂岩,夹中层-薄层状浅褐红色粉砂岩和泥岩,泥岩有弱古土壤化,其中一层为强烈发育的淋溶褐土,主要为洪泛平原沉积;上段(深度752~602 m)为红褐、褐红色块状粉砂岩和泥岩互层,夹多层深褐红色古土壤及其钙结核层,属河道间洪泛平原沉积[14](图 3c)。3)中中新世上庄组,厚92 m(深度602~510 m),年代18.0~14.8 Ma,以褐红色粉砂岩、泥岩和许多深褐红色发育钙结核的古土壤为特征,夹两层巨厚的细砂岩,共同组成两个正粒序旋回,属洪泛平原和辫状河道沉积。4)以晚中新世早期为主的东乡组,厚247 m(深度510~263 m),年代14.8~9.7 Ma,主要由近20个薄层-中层状褐灰色细砾岩、砂岩和厚层块状红褐色含细砾粉砂岩、泥岩以及它们顶部中等-强烈发育的褐红色含钙结核的古土壤组合组成,为辫状河沉积[14](图 3c)。5)晚中新世晚期柳树组,厚121 m(深度263~142 m),年代9.7~6.5 Ma,与东乡组相似,但是整体较粗,以中层状灰色砾岩与厚层-巨厚层褐黄色砂岩为主,夹多层黄褐色含砾粉砂岩和少量泥岩以及中等发育的钙质古土壤复合体,属辫状河沉积。6)早上新世何王家组,厚62 m(深度142~80 m),年代6.5~4.1 Ma,主要为黄褐色含砾粉砂岩和泥岩,夹薄层细砾岩和灰白色泥灰岩,底部发育一层弱古土壤,属辫状河沉积。7)晚上新世积石组,厚62 m(深度80~20 m),年代4.1~2.6 Ma,主要为一套巨厚、分选很差的巨砾岩组成,夹薄层砂岩,属洪积扇堆积。8)早更新世东山组,厚20 m(深度20~0 m),年代2.6~1.8 Ma,主要为灰黄色含砾砂岩、粉砂岩和泥岩以及弱古土壤组成,属辫状河沉积[14](图 3c)。

3 地层、岩相时空变化与前陆盆地构造地层岩相演化模型从时间和空间上来考察临夏盆地从盆地中央到边缘(由北向南)由毛沟—郭泥沟—黑林顶这3个剖面组成的横断面(图 2b),可以清楚地看出两个明显的特点:一是8 Ma之前,相同时段内的地层厚度由盆地中央到边缘明显增厚,沉积速率快速增加(图 3a~3c和图 4b);8 Ma之后,情况正好相反,地层厚度和沉积速率则向盆地内部增加;二是由山前到盆地中央的沉积相体系,洪积扇-辫状河-平行山系的大河和洪泛平原-湖泊体系,逐步向盆内扩展,8 Ma后扩展加快,河流变成垂直山体向外流淌的水系,导致沉积单元存在穿时现象(图 3)。由此可以推断:1)这是一个典型的山前挠曲盆地,或称陆内再生前陆盆地[8],代表了高原东北边缘的西秦岭山体由南向北对临夏盆地的冲压作用,其演化指示了高原东北边缘的隆升过程;2)8 Ma以前到至少中新世开始,高原东北边缘就开始了明显持续的向临夏盆地的冲压过程,导致山前地带持续压陷沉降,形成前渊,沉降中心与沉积中心基本吻合,沉积了较厚的沉积物,洪积扇、辫状河等粗粒沉积物则基本局限在紧靠山前的地带,广大其他地区为广泛的沿山前压陷中心形成的平行于山体的湖泊、河流及其洪泛平原体系,指示山体隆升已经持续进行,但是隆升幅度有限,山体隆升与盆地边缘压陷基本达到平衡;3)随着山体隆升的逐步增加和冲压作用的增强,上述平衡的压陷中心和地层与沉积相体系逐步向盆内迁移,导致相同地层和沉积相穿时,比如早期在郭泥沟一带湖泊沉积的斑马层标志层(对应的年代是上庄组),随压陷中心逐步向盆内中央(向北,早期处于相对翘起的前隆)毛沟一带迁移,替代早期在那里发育的洪泛平原沉积,只要其他条件不变,同样还是表现为特征的湖相斑马层,但是此时年代已经对应为东乡组了。这种沉积相体系系统迁移导致的穿时现象就会给地层对比和古气候记录研究带来影响,因而在研究时就不能简单的引用在一个地点剖面地层中找到的化石限定的地层年代,来限定盆地其他地方相似地层的年代。同样,在进行剖面古气候记录研究时,也不能仅仅依据一个地点剖面获取的古气候记录,就简单直接的认定该区古气候的变化,它很可能首先反映的是构造演化控制的沉积相迁移的变化,而非古气候的变化[14]。即沉积环境变化也控制着古气候代用指标记录的变化,特别在构造活跃地区沉积相的时空变化首先受控于盆地性质和构造演化,然后才是古气候变化等叠加其中产生影响。因此,在山前挠曲盆地研究中,仅仅通过一个剖面的古气候记录来恢复该地区的古气候变化会存在明显的不确定性(除非证明所选择的古气候代用指标与岩相无关);4)从约8 Ma以来,上述压陷中心和地层与沉积相体系向盆内迁移速率突然显著加速,位于早期压陷中心一带的黑林顶剖面上部快速被辫状河和洪积扇沉积的以砂砾岩等为主的粗粒碎屑岩代替,但是沉积速率却开始明显下降;与之相对应,早期位于前隆翘起部位的毛沟剖面,此时随着压陷中心的到来,不仅沉积相产生明显变化(早期湖泊消失,被河流沉积取代,河流流向从过去平行山体的方向变成垂直山体向盆内流动的方向),而且粒度开始变粗,沉积速率也随之明显增加,代表了压陷中心的来临使之接受了更多粗粒的沉积物堆积(图 4b)。结合其他证据[14, 16],我们还发现此时盆地开始了明显的顺时针旋转(图 4c),并伴随有断裂向盆内扩展,冲断靠近山前的盆地边缘地带,并导致其快速隆升(图 4b),而与毛沟剖面偏西约20 km、盆地靠西边的王家山一带(35.63°N,103.06°E,见图 2a),在约8 Ma开始,冲断断层还形成了显著的生长褶皱和生长地层,并同样记录了此时盆地的显著顺时针旋转[14, 16];并且,临夏盆地地层中碎屑锆石和磷灰石裂变径迹年龄变化历史还揭示出,随着盆地山前地带的隆起,早期沉积区逐步遭受剥蚀,成为新的物源区,给盆地内提供了新的物源,导致早期反映山地岩石隆升和剥蚀历史的逐步变年轻的碎屑磷灰石裂变径迹年龄,此时开始反转,碎屑磷灰石裂变径迹年龄开始逐步变老[65]。

|

图 4 临夏盆地毛沟、郭泥沟和黑林顶剖面沉积速率(b)和平均磁偏角(c) 随年代的变化及其与深海氧同位素记录的全球气候变化(a)[66]的对比修改自文献[14] Fig. 4 Variations of sedimentation rates (b) and mean paleomagnetic declinations (c) of the Heilinding, Guonigou and Maogou sections with time and their comparison with the Late Cenozoic global climate change indicated by the oxygen isotope record of synthetic benthic foraminifera of deep sea sediments[66] (a), modified from reference [14] |

需要注意的是,位于前渊的黑林顶剖面和前隆区的毛沟剖面早期分别具较高和较低的沉积速率(图 4b),在约8 Ma时(见图 4b垂直绿色阴影带)分别同时减小和增大(见图 4b灰色和紫红色阴影箭头),同时记录盆地产生显著顺时针旋转(见图 4c中紫红色阴影箭头所示),而位于两者之间的郭泥沟剖面沉积速率没有明显改变,揭示临夏挠曲盆地前渊此时向盆内的快速推进,而与全球气候变化无关。全球气候变化在一些突发事件上,如约14 Ma的中中新世全球大降温事件,对沉积速率产生重要影响并叠加在盆地构造演化机制控制的沉积速率长期规律变化的趋势上[66](图 4a)。

因此,临夏盆地上述地层和沉积体系的时空演化规律,清晰地揭示出盆地的性质(冲压拗陷的挠曲盆地)和构造演化从第一层级控制了盆地内地层的发育和沉积相演化,气候变化只能叠加在这个过程中发挥影响。挠曲盆地的构造特征和演化与经典的前陆盆地基本一样,其典型特征都可以分成楔顶、前渊、斜坡、前隆和隆后几个部分[13~14](图 1),只不过前者发育在陆内环境,属于板块的陆内变形部分,后者发育在大陆板块的前缘,属于板块边界处的陆陆碰撞。因此,早期是初始碰撞的海洋环境,碰撞发生在水下,加载体(另一大陆板块)的大小和侵蚀都是比较小的,并且加载的结果主要表现为被加载板块的前陆部分被压陷下沉,导致局部海水变深,然后随着加载体继续推进和隆升,海水再由深变浅,因而主要发育一套沉积速率较小的半深水相到浅海相的页岩、灰岩、粉砂岩和砂岩沉积体系;晚期加载体露出水面,侵蚀速率成数倍的急剧增加,主要沉积了一套由海相到陆相的以砂砾岩为主的巨厚磨拉石堆积,并伴随一系列冲断褶皱的发育[11~13, 67]。

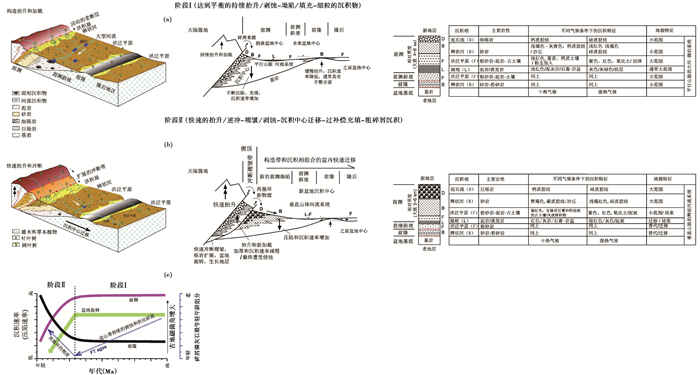

我们概括临夏盆地上述构造沉积演化,以及其他类似盆地的构造沉积研究,可以总结成以下构造地层沉积相演化模型来概述,发现挠曲盆地或陆内再生前陆盆地同样可以分成两个明显的演化阶段,即早期的冲压拗陷沉积阶段和晚期的冲断隆起向盆内扩展沉积阶段。

(1) 早期的冲压拗陷沉积阶段

这一阶段最大特点就是山体的加载和盆地的压陷基本达到平衡,也可以分为前后两个部分。前期部分主要表现为山体开始隆升,加载冲压到盆地边缘,导致盆地开始压陷,此时由于山体隆升加载有限,压陷也是缓慢和有限的;然后,随着隆升加载继续,压陷加深,山体上剥蚀下来的物质堆积在压陷中心,沉积荷载导致压陷中心进一步拗陷形成前渊,并且使压陷中心的外侧(向盆内一侧)明显反弹翘起形成前隆,两者之间有一个明显的斜坡(图 1),盆地压陷的深度和另一侧反弹翘起的高度取决于加载体的大小和盆地地壳的刚度[68~70]。当这个过程达到平衡时,山体的隆升速率、剥蚀速率和盆地压陷速率与沉积速率也达到一个动态平衡,即隆升多少物质,就可以被剥蚀和沉积埋藏多少物质,导致山体隆升的净高度是有限的且基本保持不变。因此这个时期沉积物可以很厚(取决于山体稳定加载时间的多少),物源供给和沉积速率中等,沉积物以细粒的粉砂、泥岩和细砂为主,沉积体系表现为靠近山前发育有限的洪积扇、向外变为有限的辫状河流、然后汇集到宽广的压陷中心,形成一条平行于加载山体的大河流和一系列浅湖,堆积广泛的洪泛平原和湖相沉积,沉积中心与沉陷中心吻合。此时,如果气候湿润,就会形成大量河湖沼泽泥炭甚至煤炭沉积,湖泊沉积也表现为较深水的沉积特点,如果气候干旱,则会形成大量盐湖沉积,在洪积扇和辫状河流地带还会有局地风沙和黄土堆积(图 5a)。

|

图 5 挠曲盆地构造地层沉积演化模型及气候变化对其的叠加影响(修改自文献[14]) Fig. 5 Tectonosedimentary evolution model of an intracontinental flexural basin and the possible added impacts of climatic changes on it, modified from reference [14] |

后期部分是山体开始向急剧隆升阶段过渡的时期,表现为山体开始快速隆起,山地向盆内的冲压作用加大,压陷中心逐步向盆内迁移,剥蚀量加大,沉积中心向盆内迁移速率可能大于压陷中心,但是剥蚀-压陷-沉积基本上还是维持平衡,整个沉积相体系依次随压陷和沉积中心向盆内的迁移而整体向盆内扩展,导致地层和沉积相穿时,此时只要气候没有明显改变,穿时的一套地层和沉积相特征就是一样的,极易导致在地层对比、地层测年和古气候记录研究中产生严重的误判和争论。

(2) 晚期冲断隆起向盆内扩展沉积阶段

高原内部和周边所有的挠曲盆地到了晚期阶段都表现为周边山体的强烈快速隆起,向盆地内形成快速冲压,但是盆地边缘地壳的刚度会形成顽强抵抗,压陷速率和幅度都无法消耗掉山体的快速冲压,这时盆地边缘只能以断裂和褶皱的形式,整体被冲断褶皱和缩短隆起,形成显著的冲断褶皱带,来消耗掉压陷变形以外剩余的山体冲压力。如果冲断作用持续进行,就会在山前形成几排冲断褶皱带(图 5b)。这个构造过程的沉积响应,就是早期位于冲断褶皱中的沉积,其沉积速率和厚度会随着冲断褶皱带的变形隆起而逐步减小,而沉积物粒度则逐步变粗,沉积相转变为山前洪积扇和泥石流,直至最后停止接受沉积,转变为剥蚀区,成为盆地新的物源和山体的一部分。按照经典前陆盆地的划分,这个冲断褶皱带大致相当于前陆盆地所谓的楔顶带[13]。而在冲断褶皱带的前缘原来可能属于斜坡或者前隆的地带,由于冲断褶皱带隆起和冲压以及其后山体的持续推挤,会形成一个新的压陷中心,接受来自加速隆升山地和冲断褶皱带的过量剥蚀物质,形成过补偿沉积,不仅沉积速率、粒径和地层厚度会急剧增加,并且沉积中心可能因大量沉积物的堆积而迁移速率快于压陷中心的迁移,导致沉积相体系更加快速地向盆内移动,山前洪积扇和辫状河流体系迅速扩展,甚至越过前隆地带,形成外流水系,过去平行山体分布的大河和洪泛平原-湖泊体系瓦解,形成一系列垂直山体的梳状河流体系(图 5b)。与此相对应,盆地在强大的山地推挤下,产生显著的旋转和缩短,指示物源区剥蚀历史的碎屑裂变径迹最小年龄,由早期的逐步变年轻(反映山地隆升剥蚀导致的逐步冷却过程),到晚期的反转逐步变老,记录了早期堆积在盆地边缘的物质,因冲断褶皱带的隆起而成为新的物源区的过程(图 5c)。气候变化与这个快速过程没有太大关系,其影响只能叠加在这个过程之上。如果气候湿润,仅仅是导致剥蚀速率加大、过补偿作用加强、沉积物加厚、河流作用增强,以及整个沉积中心和沉积相体系更加向盆内迁移,越过前隆区形成外流水系的概率更大,从而可以将大量的剥蚀物质沉积到挠曲盆地以外更远的地方,比如喜马拉雅前陆盆地就是一个这样的典型例子[10]。如果气候干旱,剥蚀作用会减小一些,但是快速的构造隆升仍然会使盆地处于过补偿沉积,洪积扇和辫状河流系统的快速推进和扩展,可能会使其前缘的盐湖系统难以发育,转而出现广泛的含蒸发岩的洪泛平原沉积,汇集的临时性水流会形成大河越过前隆地带向更远方的隆后盆地流淌,大量的沙源使局部风沙和黄土极易在这个系统中形成(图 5c)。例如,塔里木盆地塔西南和库车前陆盆地,它们汇集的梳状河流水系,越过前隆汇合后形成塔里木河,最终流出挠曲盆地范围,流向很远的塔里木东部的罗布泊[8]。

因此,在挠曲盆地中进行地层对比、剖面年代测定和古气候变化研究时,必须了解挠曲盆地的构造演化过程,以及上述总结的构造演化如何控制地层和沉积相时空的演化过程;另外,还必须在盆地的不同构造带中分别精细测量和定年剖面以及获取古气候记录,然后,通过系统对比,才能获得比较准确的地层对比结果和古气候变化过程。否则,一个构造带中的一个剖面研究,可能反映的仅仅是构造控制的沉积相变化,而非古气候变化。即使是远离挠曲盆地的沉积,只要沉积物是来源挠曲盆地系统的,同样因为拥有相同的剥蚀历史和物质来源,其沉积物岩性的主体及其相关的各种物理化学代用指标记录仍然是反映挠曲盆地区的构造演化信息,而不一定是沉积区的古气候变化信息。

4 结论临夏盆地是典型的山前挠曲拗陷盆地或陆内再生前陆盆地,展示出具有与前陆盆地系统相似的楔顶、前渊、前隆和隆后特征,自盆地中央向山前前渊地带地层厚度明显增厚,沉积速率加快。盆地演化可以明显分成早晚两期,早期为冲压拗陷沉积阶段,沉积相呈现规律性的由山前洪积扇、辫状河向盆地沉积中心洪泛平原和湖泊体系变化,盆地沉积中心及其中大型河流、湖泊系统与山脉保持平行;晚期为冲断褶皱阶段,约8 Ma开始,山脉开始强烈隆起,冲断褶皱和逐步隆起山前早期的前渊地带,形成冲断褶皱带并成为新的盆地物源区,并在其前缘形成新的前渊拗陷和前隆,同时盆地也开始明显缩短并旋转,导致构造体系内的上述沉积相体系随盆地构造拗陷和沉积中心向盆内迁移而产生有规律的迁移,山前洪积扇和辫状河体系快速向盆地扩展,垂直山脉的梳状河流体系代替早期平行山脉的河湖体系,并最终成为外流水系(黄河诞生),地层产生显著穿时现象,气候变化仅仅叠加在这个过程之上施加影响。上述两阶段挠曲盆地构造地层沉积演化过程具有普适性,极易导致地层对比和气候记录获取的误判,需要引起今后工作的高度重视。

致谢 感谢吴福莉和张涛协助中文图改绘。

| 1 |

刘东生等. 黄土与环境. 北京: 科学出版社, 1985: 481. Liu Tungsheng et al. Loess and Environment. Beijing: Science Press, 1985: 481. |

| 2 |

An Z S, Liu T S, Lu Y C et al. The long term paleomonsoon variation recorded by the loess-paleosol sequence in Central China. Quaternary International, 1990, 7-8: 91-95. DOI:10.1016/1040-6182(90)90042-3 |

| 3 |

An Z S, Kutzbach J E, Prell W L et al. Evolution of Asian monsoons and phased uplift of the Himalaya-Tibetan Plateau since Late Miocene times. Nature, 2001, 411(6833): 62-66. DOI:10.1038/35075035 |

| 4 |

Ding Z L, Yu Z, Rutter N et al. Towards an orbital time scale for Chinese loess deposits. Quaternary Science Reviews, 1994, 13(1): 39-70. DOI:10.1016/0277-3791(94)90124-4 |

| 5 |

Ding Z L, Xiong S F, Sun J M et al. Pedostratigraphy and paleomagnetism of a~7.0 Ma. B.P. eolian loess-red clay sequence at Lingtai, Loess Plateau, north-central China and the implications for paleomonsoon evolution. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1999, 152(1-2): 49-66. DOI:10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00034-6 |

| 6 |

Fang X M, Pan B T, Guan D H et al. A 60000-year loess-paleosol record of millennial-scale summer monsoon instability from Lanzhou, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1999, 44(24): 2264-2267. DOI:10.1007/BF02885935 |

| 7 |

Guo Z T, Biscaye P, Wei L Y et al. Summer monsoon variations over the last 1.2 Ma from the weathering of loess-soil sequences in China. Geophysical Research Letters, 2000, 27(2): 1751-1754. |

| 8 |

贾承造, 宋岩, 魏国齐等. 中国中西部前陆盆地的地质特征及油气聚集. 地学前缘, 2005, 12(3): 3-13. Jia Chengzao, Song Yan, Wei Guoqi et al. Geological features and petroleum accumulation in the foreland basins in central and western China. Earth Science Frontiers, 2005, 12(3): 3-13. |

| 9 |

高长林, 叶德燎, 钱一雄. 前陆盆地的类型及油气远景. 石油实验地质, 2000, 22(2): 99-104. Gao Changlin, Ye Deliao, Qian Yixiong. Classification of foreland basins and aspect of hydrocarbon resource. Experiment Petroleum Geology, 2000, 22(2): 99-104. DOI:10.11781/sysydz200002099 |

| 10 |

李本亮, 魏国齐, 贾承造. 中国前陆盆地构造地质特征综述与油气勘探. 地学前缘, 2009, 16(4): 190-202. Li Benliang, Wei Guoqi, Jia Chengzao. Some key tectonics characteristics of Chinese foreland basins and their petroleum exploration. Earth Science Frontiers, 2009, 16(4): 190-202. |

| 11 |

Dickinson W R. Plate tectonic and sedimentation[C]//Dickinson W R. Tectonics and Sedimentation. Tulsa:SEPM Special Publication No. 22, 1974:1-27.

|

| 12 |

Allen P A, Homewood P. Foreland Basin. Oxford: Blackwell Science Publication, 1986: 1-217.

|

| 13 |

DeCelles P G, Giles K A. Foreland basin systems. Basin Research, 1996, 8(2): 105-123. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2117.1996.01491.x |

| 14 |

Fang X M, Wang J Y, Zhang W L et al. Tectonosedimentary evolution model of an intracontinental flexural (foreland)basin for paleoclimatic research. Global and Planetary Change, 2016, 145: 78-97. DOI:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2016.08.015 |

| 15 |

方小敏, 李吉均, 朱俊杰等. 甘肃临夏盆地新生代地层绝对年龄测定与划分. 科学通报, 1997, 42(14): 1457-1471. Fang Xiaomin, Li Jijun, Zhu Junjie et al. Absolute age determination and division of the Cenozoic stratigraphy of the Linxia Basin in Gansu, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1997, 42(14): 1457-1471. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0023-074X.1997.14.001 |

| 16 |

Fang X M, Garzione C, Van der Voo R et al. Flexural subsidence by 29 Ma on the NE edge of Tibet from the magnetostratigraphy of Linxia Basin, China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2003, 210(3-4): 545-560. DOI:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00142-0 |

| 17 |

Li Jijun et al. Uplift of Qinghai-Xizang (Tibet)Plateau and Global Change. Lanzhou: Lanzhou University Press, 1995: 182.

|

| 18 |

杨钟健, 周明镇. 甘肃灵武渐新世哺乳类动物化石. 古生物学报, 1956, 4(4): 447-459. Young Chungchien, Chow Minchen. Some Oligocene mammals from Lingwu, N. Gansu. Acta Palaeontologica Sinca, 1956, 4(4): 447-459. |

| 19 |

Jiang H C, Ding Z L, Xiong S F. Magnetostratigraphy of the Neogene Sikouzi section at Guyuan, Ningxia, China. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2007, 243(1): 223-234. |

| 20 |

Wang W T, Zhang P Z, Kirby E et al. A revised chronology for Tertiary sedimentation in the Sikouzi Basin:Implications for the tectonic evolution of the northeastern corner of the Tibetan Plateau. Tectonophysics, 2011, 505(1-4): 100-114. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.04.006 |

| 21 |

Guo Z T, Ruddiman W F, Hao Q Z et al. Onset of Asian desertification by 22 Myr ago inferred from loess deposits in China. Nature, 2002, 416(6877): 159-163. DOI:10.1038/416159a |

| 22 |

Alonso-Zarza A M, Zhao Z, Song C H et al. Mudflat/distal fan and shallow lake sedimentation (upper Vallesian-Turolian)in the Tianshui Basin, Central China:Evidence against the Late Miocene eolian loess. Sedimentary Geology, 2009, 222(1): 42-51. |

| 23 |

Peng T J, Li J J, Song C H et al. Biomarkers challenge Early Miocene loess and inferred Asian desertification. Geophysical Research Letters, 2012, 39(6): 104-105. |

| 24 |

Zhang J, Li J J, Song C H et al. Paleomagnetic ages of Miocene fluvio-lacustrine sediments in the Tianshui Basin, Western China. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2013, 62: 341-348. DOI:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.10.014 |

| 25 |

Opdyke N, Flynn L, Lindsay E et al. The magnetic stratigraphy of the Yehucheng and Xianshuihe formations of Oligocene-Miocene age near Lanzhou City. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1999, 44(Suppl.1): 51-53. |

| 26 |

Qiu Z X, Wang B Y, Qiu Z D et al. Land mammal geochronology and magnetostratigraphy of mid-Tertiary deposits in the Lanzhou Basin, Gansu Province, China. Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, 2001, 94(3): 373-385. |

| 27 |

岳乐平, Heller F, 邱占祥等. 兰州盆地第三系磁性地层年代与古环境记录. 科学通报, 2001, 46(18): 1998-2002. Yue Leping, Heller F, Qiu Zhanxiang et al. Magnetostratigraphy and paleo-environmental record of Tertiary deposits of Lanzhou Basin. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2001, 46(9): 770-774. |

| 28 |

颉光普. 甘肃兰州盆地的第三纪地层及哺乳动物群. 地层学杂志, 2004, 28(1): 67-80. Xie Guangpu. The Tertiary and local mammalian faunas in Lanzhou Basin, Gansu. Journal of Stratigraphy, 2004, 28(1): 67-80. |

| 29 |

Sun D H, Zhang Y B, Han F et al. Magnetostratigraphy and palaeoenvironmental records for a Late Cenozoic sedimentary sequence from Lanzhou, northeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau. Global and Planetary Change, 2011, 76(3): 106-116. |

| 30 |

Deng Tao, Wang Xiaoming, Ni Xijun et al. Sequence of the Cenozoic mammalian faunas of the Linxia Basin in Gansu, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition), 2010, 78(1): 8-14. DOI:10.1111/acgs.2004.78.issue-1 |

| 31 |

邓涛. 临夏盆地中中新统虎家梁组的建立及其特征. 地层学杂志, 2004, 28(4): 307-312. Deng Tao. Establishment of the Middle Miocene Hujialiang Formation in the Linxia Basin of Gansu and its features. Journal of Stratigraphy, 2004, 28(4): 307-312. |

| 32 |

Deng Tao, Qiu Zhanxiang, Wang Banyue, et al. Late Cenozoic biostratigraphy of the Linxia Basin, Northwestern China[M]//Wang X M, Flynn L J, Fortelius M. Fossil Mammals of Asia:Neogene Biostratigraphy and Chronology. New York:Columbia University Press, 2013:243-273.

|

| 33 |

邱占祥, 王伴月, 邓涛. 甘肃临夏盆地牙沟的哺乳动物化石及有关地层问题. 古脊椎动物学报, 2004, 42(4): 276-296. Qiu Zhanxiang, Wang Banyue, Deng Tao. Mammal fossils from Yagou, Linxia Basin, Gansu, and related stratigraphic problems. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 2004, 42(4): 276-296. |

| 34 |

Garzione C N, Ikari M J, Basu A R. Source of Oligocene to Pliocene sedimentary rocks in the Linxia Basin in northeastern Tibet from Nd isotopes:Implications for tectonic forcing of climate. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2005, 117(9): 1156-1166. DOI:10.1130/B25743.1 |

| 35 |

邱铸鼎, 李传夔, 王士阶. 青海西宁盆地中新世哺乳动物. 古脊椎动物与古人类, 1981, 19(2): 156-173. Qiu Zhuding, Li Chuankui, Wang Shijie. Miocene mammals fossils from Xining Basin, Qinghai. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 1981, 19(2): 156-173. |

| 36 |

鹿化煜, 安芷生, 王晓勇等. 最近14 Ma青藏高原东北缘阶段性隆升的地貌证据. 中国科学(D辑), 2004, 47(9): 855-864. Lu Huayu, An Zhisheng, Wang Xiaoyong et al. Geomorphologic evidence of phased uplift of the northeastern Qinhai-Tibet Plateau since 14 million years ago. Science in China (Series D), 2004, 47(9): 822-833. |

| 37 |

Dai S, Fang X M, Dupont-Nivet G et al. Magnetostratigraphy of Cenozoic sediments from the Xining Basin:Tectonic implications for the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 2006, 111(B11): 335-360. |

| 38 |

武力超, 岳乐平, 王建其等. 新近系谢家阶层型剖面古地磁年代学研究. 地层学杂志, 2006, 30(1): 50-53. Wu Lichao, Yue Leping, Wang Jianqi et al. Magnetostratigraphy of stratotype section of the Neogene Xiejia Stage. Journal of Stratigraphy, 2006, 30(1): 50-53. |

| 39 |

Dupont-Nivet G, Krijgsman W, Langereis C G et al. Tibetan Plateau aridification linked to global cooling at the Eocene-Oligocene Transition. Nature, 2007, 445(7128): 635-638. DOI:10.1038/nature05516 |

| 40 |

Xiao G Q, Abels H A, Yao Z Q et al. Asian aridification linked to the first step of the Eocene-Oligocene climate Transition (EOT)in obliquity-dominated terrestrial records (Xining Basin, China). Climate of the Past, 2010, 6(4): 501-513. DOI:10.5194/cp-6-501-2010 |

| 41 |

Zhang W L, Zhang T, Song C H et al. Termination of fluvial-alluvial sedimentation in the Xining Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau, and its subsequent geomorphic evolution. Geomorphology, 2017, 297: 86-99. DOI:10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.09.008 |

| 42 |

Yang R S, Fang X M, Meng Q Q et al. Paleomagnetic constraints on the Middle Miocene-Early Pliocene stratigraphy in the Xining Basin, NE Tibetan Plateau, and the geologic implications. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 2017, 18: 3741-3757. DOI:10.1002/2017GC006945 |

| 43 |

Gilder S A, Chen Y, Sen S et al. Oligo-Miocene magnetostratigraphy and rock magnetism of the Xishuigou section, Subei (Gansu Province, Western China)and implications for shallow inclinations in Central Asia. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 2001, 106(B12): 30505-30521. DOI:10.1029/2001JB000325 |

| 44 |

Sun J M, Zhu R X, An Z S. Tectonic uplift in the northern Tibetan Plateau since 13.7 Ma ago inferred from molasse deposits along the Altyn Tagh Fault. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 235(3): 641-653. |

| 45 |

Charreau J, Gilder S, Chen Y et al. Magnetostratigraphy of the Yaha section, Tarim Basin (China):11 Ma acceleration in erosion and uplift of the Tian Shan Mountains. Geology, 2006, 34(3): 181-184. DOI:10.1130/G22106.1 |

| 46 |

Charreau J, Gumiaux C, Avouac J P et al. The Neogene Xiyu Formation, a diachronous prograding gravel wedge at front of the Tianshan:Climatic and tectonic implications. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2009, 287(3-4): 298-310. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.07.035 |

| 47 |

Huang B C, Piper J D A, Peng S T et al. Magnetostratigraphic study of the Kuche Depression, Tarim Basin, and Cenozoic uplift of the Tian Shan Range, Western China. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2006, 251(3-4): 346-364. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.09.020 |

| 48 |

Huang B C, Piper J D A, Qiao Q Q et al. Magnetostratigraphic and rock magnetic study of the Neogene upper Yaha section, Kuche Depression (Tarim Basin):Implications to formation of the Xiyu conglomerate formation, NW China. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 2010, 115(B1): 116-125. |

| 49 |

Sun J M, Zhang Z Q. Syntectonic growth strata and implications for Late Cenozoic tectonic uplift in the northern Tian Shan, China. Tectonophysics, 2009, 463(1-4): 60-68. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2008.09.008 |

| 50 |

Sun J M, Li Y, Zhang Z Q et al. Magnetostratigraphic data on Neogene growth folding in the foreland basin of the southern Tianshan Mountains. Geology, 2009, 37(11): 1051-1054. DOI:10.1130/G30278A.1 |

| 51 |

Sun D H, Bloemendal J, Yi Z Y et al. Palaeomagnetic and palaeoenvironmental study of two parallel sections of Late Cenozoic strata in the central Taklimakan Desert:Implications for the desertification of the Tarim Basin. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2011, 300(1-4): 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.11.015 |

| 52 |

Zhang T, Fang X M, Song C H et al. Cenozoic tectonic deformation and uplift of the South Tian Shan:Implications from magnetostratigraphy and balanced cross-section restoration of the Kuqa depression. Tectonophysics, 2014, 628: 172-187. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2014.04.044 |

| 53 |

Zheng H B, Wei X C, Tada R et al. Late Oligocene-Early Miocene birth of the Taklimakan Desert. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(25): 7662-7667. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424487112 |

| 54 |

Sun J M, Zhu R X, Bowler J. Timing of the Tianshan Mountains uplift constrained by magnetostratigraphic analysis of molasse deposits. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2004, 219(3): 239-253. |

| 55 |

Charreau J, Chen Y, Gilder S et al. Magnetostratigraphy and rock magnetism of the Neogene Kuitun He section (Northwest China):Implications for Late Cenozoic uplift of the Tianshan Mountains. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2005, 230(1-2): 177-192. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2004.11.002 |

| 56 |

Charreau J, Chen Y, Gilder S et al. Neogene uplift of the Tian Shan Mountains observed in the magnetic record of the Jingou River section (Northwest China). Tectonics, 2009, 28(2): 224-243. |

| 57 |

Ji J L, Luo P, White P D et al. Episodic uplift of the Tianshan Mountains since the Late Oligocene constrained by magnetostratigraphy of the Jingou River section, in the southern margin of the Junggar Basin, China. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 2008, 113: B05102. DOI:10.1029/2007JB005064 |

| 58 |

Li C X, Dupont Nivet G, Guo Z J. Magnetostratigraphy of the northern Tian Shan foreland, Taxi He section, China. Basin Research, 2011, 23(1): 101-117. DOI:10.1111/bre.2011.23.issue-1 |

| 59 |

庞丽波. 甘肃临夏盆地石磊地点的三趾马化石. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(3): 502-512. Pang Libo. Hipparion (Equidae, Perissodactyla)fossils from the Shilei locality of the Linxia Basin, Gansu Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(3): 502-512. |

| 60 |

卢小康, 陈善勤, 何文. 临夏盆地晚新近纪山西犀头骨新材料及其生存环境. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(3): 539-549. Lu Xiaokang, Chen Shanqin, He Wen. New skulls of Shansirhinus ringstroemi from the Upper Neogene of the Linxia Basin, and their paleoenvironmental context. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(3): 539-549. |

| 61 |

李刈昆. 甘肃临夏盆地晚中新世杨家山动物群的瞪羚化石. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(3): 550-560. Li Yikun. Gazella fossils of the Late Miocene Yangjiashan fauna from the Linxia Basin, Gansu Province. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(3): 550-560. |

| 62 |

Wu F L, Fang X M, Meng Q Q et al. Magneto-and litho-stratigraphic records of the Oligocene-Early Miocene climatic changes from deep drilling in the Linxia Basin, northeast Tibetan Plateau. Global and Planetary Change, 2017, 158: 36-46. DOI:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2017.09.008 |

| 63 |

Reading H G. Sedimentary Environments:Processes, Facies and Stratigraphy (3rd Edition). London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 704.

|

| 64 |

Li J J, Fang X M, Van der Voo R et al. Magnetostratigraphic dating of river terraces:Rapid and intermittent incision by the Yellow River of the northeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau during the Quaternary. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 1997, 1021(B5): 10121-10132. |

| 65 |

郑德文, 张培震, 万景林等. 青藏高原东北边缘晚新生代构造变形的时序——临夏盆地碎屑颗粒磷灰石裂变径迹记录. 中国科学(D辑), 2003, 46(z1): 190-198. Zheng Dewen, Zhang Peizhen, Wan Jinglin et al. Cenozoic deformation subsequence in northeastern margin of Tibet-Detrital AFT records from Linxia Basin. Science in China (Series D), 2003, 46(z2): 266-275. |

| 66 |

Zachos J C, Pagani M, Sloan L et al. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science, 2001, 292(5517): 686-693. DOI:10.1126/science.1059412 |

| 67 |

Covey M. The evolution of foreland basins to steady state:evidence from the Western Taiwan Foreland Basin[C]//Allen P A, Homewood P. Foreland Basins. Internationl Association of Sedimentologists Special Publication 8, 1986:77-90.

|

| 68 |

Beaumont C. Foreland basins. Geophysical Journal International, 1981, 65(2): 291-329. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1981.tb02715.x |

| 69 |

Stockmal G S, Beaumont C, Boutilier R. Geodynamic models of emergent margin tectonics:Transition from rifted margin overthrust belt and consequences for foreland-basin development. AAPG Bulletin, 1986, 70(2): 181-190. |

| 70 |

Sinclair H D, Coakley B J, Allen P A et al. Simulation of foreland basin stratigraphy using a diffusion model of mountain belt uplift and erosion:An example from the central Alps, Switzerland. Tectonics, 1991, 10(3): 599-620. DOI:10.1029/90TC02507 |

2 CAS Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Beijing 100101;

3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049)

Abstract

Intracontinental flexural (foreland)basin is one of the most common occurred basins in the continent. It is widely distributed in and around the Tibetan Plateau. Its striking features are the remarkable flexural depression and thrust-fold of basin marginal basement and sediments due to loading of nearby mountains from push, which strictly control the evolution of the basin tectonics and the development of the stratigraphy and sedimentary facies. The sediments in such basin are now frequently used as archives for detailed paleoclimatic and sedimentary environmental reconstruction, fossil and stratigraphic correlation, and tectonic evolution and uplift of basin and orogen. However, sedimentologic characteristics vary considerably in time-space with the evolution of flexural basin, apt to cause misinterpretation of climatic change and stratigraphic correlation. Especially for those who are used to study climatic changes using homogeneous sediments, such as eolian dust deposits, or on more or less stable sediments in down-faulting basins with less lateral sedimentary facies variation, it is more at risks to make serious mistakes. Perhaps this is one of the major reasons why there are so many serious contradictions in age determination of stratigraphy, paleontological vs. paleomagnetic stratigraphy correlation, sedimentary facies and climatic records and changes in basins in Western China. Based on high resolution fossil mammal and magnetostratigraphic constraints and sedimentary facies analysis, here we take the Linxia Basin at the front of the NE Tibetan Plateau as a case to demonstrate and figure out a model how sedimentology and stratigraphy vary temporospatially with the evolution of such flexural basin, which at first order strictly control the proxy climatic records, thus climatic change history. We wish our research could shed light on making clear many of the differences or contradictions in basin stratigraphy and climatic studies in Western China. The results show that the typical intracontinental foreland Linxia Basin experienced two phases, the early subsidence and the late thrust-fold, of flexural deformation exerted by the West Qinling (Mts.)and NE Tibetan Plateau to the south. The early subsidence phase manifests as the basin being mainly subjected to flexural depression mostly in response and balance with pushing and loading mountains, during which the uplift and erosion of the loading mountains are generally in balance with supplying and infilling of mostly fine sediments to flexural basin, forming remarkable sediment wedge in the foredeep. In the Linxia Basin, this commenced latest at the beginning of the Late Oligocene (26.5 Ma). During such tectonosedimentary environment, a big river-shallow lake system develops along the foredeep and parallels the pushing and loading mountains. The late thrust-fold phase is characterized with the loading mountains begin to uplift rapidly and thrust onto the basin, causing strong mountain erosion, thrust-fold belt propagation and basin overfilling. This forced the mountains-parallel river-lake system to turn to the mountains-perpendicular alluvial-braided river system, and finally to an outflow system. Concurrent are rapid rotation of the basin, occurrence of growth strata and late unconformities, widespread expansion of boulder conglomerates, great decreasing and increasing sedimentation rates above and before the hanging wall of the fault-fold system and new supplementary provenance from the thrust-fold system. In the Linxia Basin, this phase began at ca. 8 Ma. This demonstrates that in stable climate, same lithologic units such as distinct lacustrine sediments and alluvial conglomerates will migrate basinwards with the foredeep moving into basin, causing a great diachroneity and often misleads to recognize the same lithologic unit in space as one unit in time. 2018, Vol.38

2018, Vol.38