② 中国科学院大学人文学院, 考古学与人类学系, 北京 100049;

③ 大庆博物馆, 大庆 163316)

真猛犸象(Mammuthus primigenius)(又称“长毛猛犸象”)是猛犸象属中最著名的一种,它于中更新世起源于西伯利亚,然后迁徙至欧洲、中国、日本等地,甚至穿越白令海峡到达北美[1~3]。在更新世晚期,以真猛犸象为代表的动物群,包括披毛犀、马科、牛科、鹿科、熊科及小猫科动物等,占据了大部分的北半球高纬度区域。然而,以真猛犸象、披毛犀为代表的大型植食动物(megaherbivores),却最终走向了灭绝,成为更新世晚期的重大生物事件[4~7]。

众所周知,食物的获取,在动物的生存和演化过程中扮演着极为重要的角色。真猛犸象究竟以何为食,以及其食物来源是否对真猛犸象的灭绝产生了重要的影响,一直都是真猛犸象研究的重要组成部分。

近些年来,真猛犸象化石的C、N稳定同位素分析,逐渐成为探索其食物结构的主流研究方法之一[8]。西伯利亚、东欧和北美等多个地区真猛犸象化石的同位素数据显示:真猛犸象主要以C3类植物为食;尤其值得一提的是,绝大部分真猛犸象的δ15N值,高于伴生的食草动物而与食肉动物相似[9~14]。显然,真猛犸象的摄食行为,明显异于其他的食草动物,可能与其独特的食物来源、生理特征等密切相关[14, 15]。

作为真猛犸象及伴生动物群曾经活跃过的重要区域之一的我国东北地区,也发现了大量的更新世晚期的真猛犸象化石[16~20]。然而,迄今为止,该地区真猛犸象的食物来源与其他地区是否存在相似性,尚无任何报道。为此,本文以我国东北地区晚更新世的真猛犸象及伴生动物群为研究对象,通过稳定碳、氮同位素分析,在揭示它们食物来源的基础上,探讨真猛犸象的摄食行为,并结合已有的世界其他地区真猛犸象的同位素数据,探讨真猛犸象食物来源的特点及对其灭绝可能存在的影响。

2 碳、氮稳定同位素分析原理由于光合作用途径的不同,植物可分为C3、C4和CAM三种类型[21],相应地,不同种类的植物δ13C值也各不相同。现代陆生C3植物(乔木和大部分草本植物)的δ13C值范围介于-32 ~-22,平均值为-26.5;C4植物(包括狗尾草、莎草科等部分草本植物)的δ13C值介于-16.5 ~-9.5,平均值为-12.5 [22~24]。北半球的高纬度地区,基本是以C3植物为主导的生态环境[25, 26]。然而,环境因素和植物自身的新陈代谢差异,导致不同植物种属的δ13C值也存在一定的差异[27, 28]。例如:苔藓相比于其他维管植物有着较高的δ13C值,草、莎草等植物的δ13C值相对较低,灌木及木本植物的δ13C值居中[28~31];此外,菌类植物的δ13C值,近似于苔藓[32]。

这种植物之间存在的碳同位素比值差异,在食物链的物质能量流动过程中始终存在。动物身体组织的同位素比值,直接取决于其食物,但存在着一定程度的同位素分馏。一般认为,与所吃食物的δ13C值相比,动物肌肉中的δ13C富集约1,骨胶原中的δ13C会富集约5,故此,通过动物身体组织δ13C值,即可了解其食物的主要类型[33, 34]。

不同于碳,大气中的N2通常很难被植物直接吸收。只有一些固氮植物,主要为豆科、藻类和菌类植物,可以依靠与其共生的微生物直接转化大气中的N2而吸收氮,这一过程中基本不存在同位素的分馏,所以一般豆科植物的δ15N几乎等于零[35~37];而其他植物则需要吸收从NH3转化而来的NO3-和NH4+盐来获取维持正常生理功能所需的氮源[38, 39]。在氮的转化过程中,其同位素值将发生分馏,致使δ15N发生一定程度的富集[38, 39]。在北半球高纬度地区的生态环境中,草、莎草科及真菌类植物具有最高的δ15N值,苔藓的δ15N值次之,灌木及叶片的δ15N值最低[14, 30]。而在食物链的上升过程中,每上升一个营养级,生物的δ15N值将富集约3 ~5,即植食动物的δ15N值较其所食植物高3 ~5,食肉动物又较其所食的植食动物高3 ~5 [40]。

然而,需要指出的是,外界环境以及生物新陈代谢的异常,将对动植物的δ15N值造成不同程度的影响。例如,温度、降水、土壤条件和盐分状况等外界环境因素发生改变,均可引起植物δ15N值的变化;对于动物而言,外界环境、自身新陈代谢及饮食压力等因素,也会影响其正常的δ15N值[41, 42]。因此,当生物的δ15N值异常时,需对其可能的影响因素加以考虑。

3 材料与方法 3.1 样品选取本次研究的样品,均来自于黑龙江省大庆博物馆。大庆博物馆是国内首家以东北第四纪古生物和古环境为主题的综合性博物馆,经过十余年的努力,现已发展成为国内第四纪哺乳动物化石的收藏中心和展示中心,馆藏化石20余万件,已成为全国乃至世界上,专业性收藏猛犸象及伴生动物群化石种属最全、数量最多的博物馆之一,填补了东北第四纪古生物化石系统收藏的空白。本次研究采集的样品来自黑龙江省青冈县、肇源县等地,虽无确切出土地点和层位,但根据东北地区晚更新世动物群的特点,可推测其时代为距今约4万至1万年[6, 18]。

本次选取的动物骨骼,包括9个种类,共33例(见表 1)。这些样品包括:均为成年个体的真猛犸象(Mammuthus primigenius)(n=6),还有披毛犀(Coelodonta antiquitatis)(n=3)、普氏野马(Equus przewalskii)(n=4)、牛科(Bovidae)(n=5)、鹿科(Cervidae)(n=5)、棕熊(Ursus arctos)(n=3)、猫(Felis sp.)(n=3)、赤狐(Vulpes vulpes)(n=2) 和禽类(n=2)。

3.2 骨胶原提取根据Jay和Richards[43]的流程并略作修改。机械去除骨骼表面的污染物质,超声波清洗干燥。称取2g左右的样品,置于0.5M盐酸在4℃下脱钙,每隔一天更换酸液,直至样品松软无气泡。去离子水冲洗至中性,于0.125M的NaOH溶液中4℃下浸泡20小时,再次冲洗至中性。加入0.001M盐酸,70℃明胶化约48小时,过滤、冷冻干燥得到骨胶原。称重,计算骨胶原得率(骨胶原重量/骨样重量,结果见表 1)。

| 表 1 大庆博物馆真猛犸象及伴生动物群的稳定同位素测试结果及相关信息 Table 1 Isotopic data and other detailed information of mammoth fauna from Daqing Museum |

骨胶原样品的C、N元素含量及其稳定同位素比值,在中国科学院大学考古稳定同位素实验室进行。测试仪器为元素分析仪(Elementar Vario)联用的同位素质谱仪(IsoPrime 100 IRMS)。骨胶原的C、N含量测定的标准物质为磺胺(Sulfanilamide)。同位素测试和校正的国际标准物质为Caffeine,IAEA-N-2,IAEA-CH-6,USGS 40 and USGS 41。每10个样品穿插一组标准样品,同时还加入骨胶原实验室标准物质(δ13C:14.7±0.2,δ15N:6.9±0.2) 对测试样品的数据进行监控。实验室的δ13C和δ15N测试误差均小于±0.2。用国际标准物质USGS 40和USGS41的测试结果,制作标准曲线对样品的测试数据进行校正。所有样品的同位素数据,如表 1所示。

4 结果 4.1 骨骼污染的鉴别骨骼在长期的埋藏过程中,是否依然保持其起初的生物学特性和化学成分,是开展稳定同位素分析的基础。因此,鉴别骨骼受污染的程度,是开展同位素分析的前提条件[44~46]。

通常,骨胶原得率、C、N元素含量和C、N摩尔比,是了解骨胶原保存状况的重要指标[47]。现代骨骼的骨胶原含量一般在20 %左右[48]。本研究中骨胶原得率的均值,为10.2±3.6 (n=33),虽低于现代样品,但相对于其他考古遗址仍相对较高,这可能与其地处东北寒冷的环境有关[49~52]。此外,保存较好的骨胶原,其C、N元素含量应分别位于15.3 % ~47.0 %和5.5 % ~17.3 %范围内,且C、N摩尔比值也应介于2.9~3.6之间[53]。如表 1中所示,本次研究提取出的33个骨胶原,C、N元素含量分别位于20.3 ~45.0和7.6 ~16.4范围内,C、N摩尔比为3.0~3.6,表明其基本未受污染,可用于以下分析。

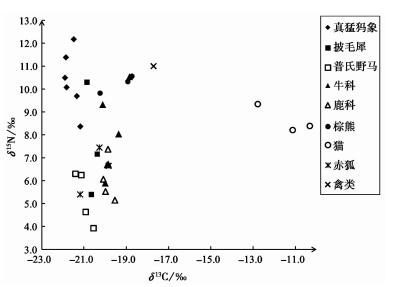

4.2 C、N稳定同位素分析所有样品同位素数据的散点图,如图 1所示,从中可见,各种动物的同位素数据存在一定的差异,反映了它们具有不同的食物来源。

|

图 1 大庆博物馆真猛犸象及伴生动物群C、N同位素数据散点图 Fig. 1 The scatter plot of δ13C and δ15N values of mammoth fauna fossils from Daqing Museum |

鹿科动物和普氏野马,是本研究中食草动物的典型代表。由图 1可以看出,两者的同位素数据基本相似。两种动物皆显现出摄食C3植物的特征,但鹿科动物的δ13C值(均值为-19.9±0.2,n=5) 略大于普氏野马(均值为-21.0±0.4,n=4),表明其可能摄取了较高δ13C值的植物。此外,两种动物的δ15N值,也较为相近,但鹿科动物的δ15N值(均值为6.2±0.9,n=5),稍高于普氏野马(均值为5.3±1.2,n=4)。两种动物的δ15N平均值,为5.8±1.1 (n=9),表现出典型的食草动物特征。

相比于以上食草动物,肉食动物的同位素数据则相差较大(图 1)。猫的δ13C均值高达-11.4±1.3 (n=3),表明其摄取了大量的C4类食物。其他肉食动物,皆显示出以C3类为主食的同位素特征,但δ15N值却存在一定的差异。棕熊的δ15N值最大,其均值为10.2±0.4 (n=3)。赤狐的δ15N值低于棕熊,它们分别为5.4和7.4,表明其食物主要来源于低δ15N值的小动物。至于禽类,两个个体的同位素数据则相差较大,可能与其属于不同鸟类的种属相关。鉴于以上动物的同位素数据,本研究中以棕熊和猫的δ15N值作为食肉类动物的代表,其平均值为9.4±1.0 (n=6)。

在建立了食草类动物与食肉类动物的δ15N同位素基线(isotope baseline)之后,我们即可对其他动物(真猛犸象、披毛犀、牛科)的同位素数据进行深入分析。由图 1可见,真猛犸象的δ15N值普遍较高,均值为10.4±1.3 (n=6),已高于食肉类动物,明显异于食草类动物。牛科虽属公认的食草类动物,但其δ15N值却分布较广(5.9 ~10.5),均值为8.1±1.9 (n=5),甚至有些个体的δ15N值已接近于食肉类动物。与牛科相似,披毛犀的δ15N值也相差较大,但其较高的δ15N均值(7.6±2.5,n=3),也高于食草类动物。

5 讨论 5.1 我国东北地区真猛犸象及伴生动物群的食物结构如前所述,由于所食植物类型和种属的不同,食草类动物的δ13C和δ15N值也可能存在一定的差异。在本研究中(图 1和表 1),鹿科的δ13C值较高而δ15N值很低,可能与其食物中包括一定量的苔藓和植物叶片相关。对于普氏野马,其δ15N值最低,反映了其摄入较大量的灌木。相对于食草动物,食肉动物的情况就较为复杂,以棕熊和猫为代表的典型食肉动物,其δ15N均值与食草动物(鹿科和普氏野马)的差异为3.6,落于δ15N值沿营养级上升的分馏富集值范围(3 ~5)。由此,通过以上动物建立的同位素食物链(isotopic foodweb),就为探讨其他动物的食物来源奠定了基础。

更新世晚期东北地区真猛犸象及伴生动物群中的牛科动物以草原野牛(Bison priscus)和原始牛(Bos primigenius)为代表[17, 54],两者虽兼属食草动物(grazer),但其分布范围较大的同位素数据(见图 1),则明显反映出其食物来源较为广泛,可能代表牛科动物可以栖息于多种生态环境;披毛犀的同位素数据也分布较广,可能与其具有较广的活动范围和食物来源相关;对于赤狐而言,其在所有动物中具有居中的δ15N值,并未显示出典型的食肉动物的同位素特征,这可能与其食物中包含低δ15N值的小型动物(本研究中未能取样)相关;至于禽类,因种属不明,两个个体的同位素数据显现出极大的差异。一个个体与食草类动物相似,应主要以陆生植物为食;另外一个个体,具有高δ13C和δ15N值,表明其食物中包含了大量的水生类资源[55, 56]。

与其他所有动物相比,真猛犸象的同位素数据呈现出δ13C均值最低,而δ15N均值最高的分布特点。其中,真猛犸象异常高的δ15N值最引人关注。如图 1所示,真猛犸象的同位素数据较为集中,其δ15N值近似于食肉动物,与食草动物相差显著。显然,真猛犸象的食物来源有其独特之处。本文在此方面的研究,不仅属国内首例,也为全面探讨中国境内真猛犸象的摄食行为奠定了基础。

就全球范围而言,真猛犸象骨胶原具有高δ15N值的现象,不仅出现在中国东北地区,也普遍存在于世界其他地区[14, 15, 57]。那么,产生这种现象的主要因素究竟何在,是学术界关注的焦点。为此,学者们提出了多个方面的影响因素。

(1) 外界环境。尽管营养级的上升是造成生物δ15N值升高的主导因素,但外界环境因素,诸如干旱、盐度等,可对植物的δ15N值产生极大的影响,致使生存于不同生态环境之下的生物具有不同的δ15N值[14, 32, 58]。由此可见,真猛犸象食物中的植物,应不同于其他动物所栖息的生态环境。Schwartz-Narbonne等[57]通过对猛犸象及相关动物骨胶原中氨基酸δ15N值的测定和分析,进一步指出其觅食环境明显异于其他食肉和食草动物。

(2) 生理特征。真猛犸象属于盲肠动物(hindgut fermenter),其肠道相比于牛科、鹿科等反刍动物较短,摄取养分能力较差[59, 60]。由于作为其食物的植物皆具有较低的蛋白含量,可能无法满足其正常的新陈代谢。故此,真猛犸象自身应普遍存在着体内氮的循环利用,导致其δ15N值的富集[14, 15, 59~61]。

(3) 食粪行为。研究显示,由于食物短缺、营养不良等因素,现代象群存在自食或互食粪便的独特行为,尤其在幼象中更为普遍[15]。动物学家也普遍认为由于象类自身消化植物能力较低,幼象通过这种独特的行为获取消化系统中发酵植物纤维的益生菌[62]。而在冰原冻土中保存的猛犸象尸体中也存在类似的食粪行为[15, 63, 64]。除了直接的食粪行为,一些学者推测由于猛犸象食量大,排便多,因此其所处的生态领域内土壤的粪便含量高,所以生长其中的植物便具有较高的δ15N值[57, 65]。故此,猛犸象这种直接或者间接的食粪行为,都有可能是造成其高δ15N值的重要因素。

需要指出的是,尽管以上各种因素,可能无法完全揭示真猛犸象高δ15N值的原因,但无论如何,与其他动物相比真猛犸象具有迥异的食物来源和栖息环境,却是不争的事实。

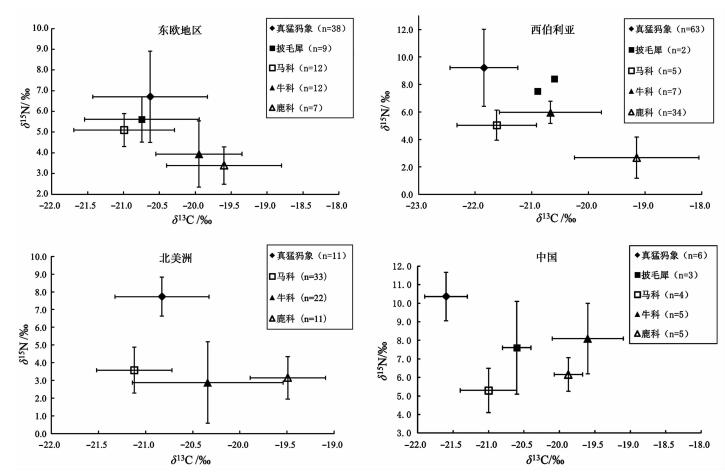

5.2 真猛犸象的摄食行为对其绝灭的影响目前,对于真猛犸象在更新世晚期的灭绝事件,学术界提出了两种假说,即人类过度的狩猎捕杀和由于环境因素导致的猛犸象食物来源短缺[66~70]。在此,我们收集了已发表的真猛犸象及主要伴生动物群的同位素数据(如表 2所示),进一步验证第二个假说的可能性。主要比较的对象是真猛犸象、披毛犀、马科、牛科和鹿科。在以下分析中,我们按照东欧地区[10, 16, 71, 72]、西伯利亚[9~11, 73]、北美洲[32, 65, 73]和中国(见图 2),对全世界范围内的真猛犸象的食物结构进行讨论。

| 表 2 不同地区已发表的真猛犸象及其主要伴生食草动物的C、N同位素数据汇总 Table 2 Published δ13C and δ15N values of Mammuthus primigenius and predominant coexisting herbivores from different regions |

|

图 2 已发表的真猛犸象及主要伴生食草动物的C、N同位素数据分布图 Fig. 2 Summarized diagram of published δ13C and δ15N values of Mammuthus primigenius and predominant coexisting herbivores from different regions |

东欧地区、西伯利亚、北美洲和中国的真猛犸象样品,δ15N值均值分别为6.7±2.2 (n=38)、9.2± 2.8 (n=63)、7.7±1.1 (n=11) 和10.4±1.3 (n=6);而这4个地区其他食草动物的δ15N均值分别为4.6± 1.4 (n=40)、3.6±2.1 (n=48)、3.3± 1.7 (n=66) 和6.8±1.9 (n=17),与真猛犸象相差分别为2.1、5.6、4.4和3.6。

由图 2可见,无论处在哪个地区,真猛犸象的δ15N值,都是以上分析动物的最高值。而真猛犸象的δ13C值普遍处于相对较低的水平,在西伯利亚和中国,真猛犸象的δ13C值均最低。此外,相对而言,真猛犸象的同位素数据,具有较小的标准偏差,反映了该动物的食物来源普遍较为稳定。综上,可以看出,真猛犸象的食物来源异于其他动物,专门化程度较高。

众所周知,更新世晚期的气候,极为动荡[74~77]。冰河时代的存在,对所有动物的生存提出了严峻的挑战。然而,根据以上统计的全世界范围内真猛犸象的同位素数据可知:真猛犸象的食物选择范围较为狭窄,缺乏广谱性,也代表其所处的生态域(ecological niche)较为固定和局限,这可能是其无法在更新世末期剧烈的环境变化和残酷的种间竞争中生存的主要原因之一。

6 结论本研究利用C、N稳定同位素分析,首次揭示了中国东北地区晚更新世真猛犸象及伴生动物群的摄食行为,发现除了猫摄入C4类食物以外,整个动物群都是纯C3类的食物来源。其中,真猛犸象的δ13C值最低(-21.6±0.3,n=6),而δ15N值最高(10.4±1.3,n=6),这明显异于其他的食草动物,非常特殊。真猛犸象异常高的δ15N值,可能受干旱的外界环境、自身生理特征、食粪行为等诸多因素的影响。通过与东欧、西伯利亚和北美洲的真猛犸象及主要的伴生食草动物(披毛犀、马科、牛科及鹿科)C、N同位素数据的整理和对比分析,发现所有地区中真猛犸象的δ15N值均最高,而其δ13C值都相对较低,代表真猛犸象相比于其他食草动物具有独特的摄食行为。真猛犸象的C、N同位素数据揭示出其异于其他动物的摄食行为,反映出其食物专门化程度较高,生态领域较为狭窄、稳定,可能导致其无法适应更新世晚期较为激烈的气候变化,这可能是真猛犸象最终走向灭绝的重要原因之一。

致谢: 特别感谢英国布里斯托大学的张瀚文同学帮助改正英文摘要和校正文章内容;此外,中国科学院大学科技考古专业的王婷婷、王欣、张昕煜、Benjamin Fuller博士等为这篇文章提出了宝贵意见,在此一并感谢。同时,也非常感谢审稿专家提出的宝贵建议和本刊编辑对本文的修改建议和耐心勘误。

| 1 |

Lister A M, Sher A V. The origin and evolution of the woolly mammoth. Science, 2001, 294(5544): 1094-1097. DOI:10.1126/science.1056370 |

| 2 |

Lister A M, Sher A V, Essen H V, et al. The pattern and process of mammoth evolution in Eurasia. Quaternary International, 2005, 126-128: 49-64. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.014 |

| 3 |

魏光飚, 胡松梅, 余克服, 等. 草原猛犸象(Mammuthus trogontherii)新材料及猛犸象的起源与演化模式探讨. 中国科学:地球科学, 2010, 53(6): 715-723. Wei Guangbiao, Hu Songmei, Yu Kefu, et al. New materials of the steppe mammoth, Mammuthus trogontherii, with discussion on the origin and evolutionary patterns of mammoths. Science China:Earth Sciences, 2010, 53(7): 956-963. |

| 4 |

Kahlke R D. The origin of Eurasian mammoth faunas(Mammuthus-Coelodonta faunal complex). Quaternary Science Reviews, 2014, 96(13): 32-49. |

| 5 |

Lõugas L, Ukkonen P, Jungner H. Dating the extinction of European mammoths:New evidence from Estonia. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2002, 21(12): 1347-1354. |

| 6 |

张虎才. 我国东北地区晚更新世中晚期环境变化与猛犸象-披毛犀动物群绝灭研究综述. 地球科学进展, 2009, 24(1): 49-60. Zhang Hucai. A review of the study of environmental changes and extinction of the Mammuthus-Coelodonta fauna during the middle-late Late Pleistocene in Northeast China. Advances in Earth Science, 2009, 24(1): 49-60. |

| 7 |

Kuzmin Y V. Extinction of the woolly mammoth(Mammuthus primigenius)and woolly rhinoceros(Coelodonta antiquitatis)in Eurasia:Review of chronological and environmental issues. Boreas, 2010, 39(2): 247-261. DOI:10.1111/bor.2010.39.issue-2 |

| 8 |

Metcalfe J Z. Proboscidean isotopic compositions provide insight into ancient humans and their environments. Quaternary International, 2017. |

| 9 |

Bocherens H, Pacaud G, Lazarev P A, et al. Stable isotope abundances(13C, 15N) in collagen and soft tissues from Pleistocene mammals from Yakutia:Implications for the palaeobiology of the Mammoth Steppe. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1996, 126(1-2): 31-44. DOI:10.1016/S0031-0182(96)00068-5 |

| 10 |

Iacumin P, Nikolaev V, Ramigni M. C and N stable isotope measurements on Eurasian fossil mammals, 40000 to 10000 years BP:Herbivore physiologies and palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2000, 163(1): 33-47. |

| 11 |

Iacumin P, Di Matteo A, Nikolaev V, et al. Climate information from C, N and O stable isotope analyses of mammoth bones from northern Siberia. Quaternary International, 2010, 212(2): 206-212. DOI:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.10.009 |

| 12 |

Koch P L, Hoppe K A, Webb S D. The isotopic ecology of Late Pleistocene mammals in North America:Part 1.Florida. Chemical Geology, 1998, 152(1): 119-138. |

| 13 |

Feranec R S, MacFadden B J. Evolution of the grazing niche in Pleistocene mammals from Florida:Evidence from stable isotopes. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2000, 162(1): 155-169. |

| 14 |

Bocherens H. Isotopic biogeochemistry and the paleoecology of the mammoth steppe fauna. In:Reumer J W F, de Vos J, Mol D eds. Advances in Mammoth Research:Proceedings of the Second International Mammoth Conference Rotterdam, 16~20 May, 1999. Deinsea, 2003, 9 :57~76

|

| 15 |

Kuitems M, van Kolfschoten T, van der Plicht J. Elevated δ15N values in mammoths:A comparison with modern elephants. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 2015, 7(3): 289-295. DOI:10.1007/s12520-012-0095-2 |

| 16 |

姜鹏. 东北猛犸象披毛犀动物群初探. 东北师大学报(自然科学版), 1982(1): 105-115. Jiang Peng. Prliminary probe on Mammuthus-Coelodonta fauna of North-Eastern China. Journal of Northeast Normal University(Nature Sciences), 1982(1): 105-115. |

| 17 |

金昌柱, 徐钦琦. 中国晚更新世猛犸象(Mammuthus)扩散事件的探讨. 古脊椎动物学报, 1998, 36(1): 47-53. Jin Changzhu, Xu Qinqi. On the dispersal events of Mammuthus during the Late Pleistocene. Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 1998, 36(1): 47-53. |

| 18 |

张云翔, 李永项, 谢坤, 等. 末次冰期东北地区食草动物群的演替及其环境意义. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(3): 622-630. Zhang Yunxiang, Li Yongxiang, Xie Kun, et al. Succession large herbivorous faunas and environmental evolution in Northeast China during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(3): 622-630. |

| 19 |

陈军, 尹勇前, 李涛, 等. 吉林省大布苏国家重点化石产地的猛犸象-披毛犀动物群. 地质通报, 2016, 35(6): 872-878. Chen Jun, Yin Yongqian, Li Tao. The Mammuthus-Coelodonta Fauna from Dabusu National Key Fossil Locality, Jilin Province. Geological Bulletin of China, 2016, 35(6): 872-878. |

| 20 |

Tong H W, Patou-Mathis M. Mammoth and other proboscideans in China during the Late Pleistocene. In:Reumer J W F, de Vos J, Mol D eds. Advances in Mammoth Research:Proceedings of the Second International Mammoth Conference Rotterdam, 16~20 May 1999. Deinsea, 2003, 9 :421~428

|

| 21 |

O'Leary M H. Carbon isotope fractionation in plants. Phytochemistry, 1981, 20(4): 553-567. DOI:10.1016/0031-9422(81)85134-5 |

| 22 |

Farquhar G D, Ehleringer J R, Hubick K T. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 1989, 40(1): 503-537. DOI:10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443 |

| 23 |

Ehleringer J R, Field C B, Lin Z, et al. Leaf carbon isotope and mineral composition in subtropical plants along an irradiance cline. Oecologia, 1986, 70(4): 520-526. DOI:10.1007/BF00379898 |

| 24 |

张红艳, 鹿化煜, 顾兆炎, 等. 中国半干旱-湿润区末次间冰期以来黄土有机碳同位素特征与植被变化. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(4): 809-818. Zhang Hongyan, Lu Huayu, Gu Zhaoyan, et al. Organic matter stable isotopic composition of loess deposits in semiarid to humid climate regions of China and the vegetation variations since the Last Interglaciation. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(4): 809-818. |

| 25 |

Cerling T E, Harris J M, MacFadden B J, et al. Global vegetation change through the Miocene/Pliocene boundary. Nature, 1997, 389(6647): 153-158. DOI:10.1038/38229 |

| 26 |

Ding Z L, Yang S L. C3/C4 vegetation evolution over the last 7.0 Myr in the Chinese Loess Plateau:Evidence from pedogenic carbonate δ13C. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2000, 160(3): 291-299. |

| 27 |

Tieszen L L. Natural variations in the carbon isotope values of plants:Implications for archaeology, ecology, and paleoecology. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1991, 18(3): 227-248. DOI:10.1016/0305-4403(91)90063-U |

| 28 |

Heaton T H E. Spatial, species, and temporal variations in the 13C/12C ratios of C3 plants:Implications for palaeodiet studies. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1999, 26(6): 637-649. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1998.0381 |

| 29 |

张博, 宁有丰, 安芷生, 等. 黄土高原现代C4和C3植物生物量及其对环境的响应. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(4): 801-808. Zhang Bo, Ning Youfeng, An Zhisheng, et al. Abundance of C4/C3 plants in the Chinese Loess Plateau and their response to plant growing environment. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(4): 801-808. |

| 30 |

Fizet M, Mariotti A, Bocherens H, et al. Effect of diet, physiology and climate on carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes of collagen in a Late Pleistocene anthropic palaeoecosystem:Marillac, Charente, France. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1995, 22(1): 67-79. DOI:10.1016/S0305-4403(95)80163-4 |

| 31 |

Máguas C, Brugnoli E. Spatial variation in carbon isotope discrimination across the thalli of several lichen species. Plant, Cell & Environment, 1996, 19(4): 437-446. |

| 32 |

Fox-Dobbs K, Leonard J A, Koch P L. Pleistocene megafauna from eastern Beringia:Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental interpretations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and radiocarbon records. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2008, 261(1-2): 30-46. DOI:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.12.011 |

| 33 |

DeNiro M J, Epstein S. Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1978, 42(5): 495-506. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0 |

| 34 |

Sullivan C H, Krueger H W. Carbon isotope analysis of separate chemical phases in modern and fossil bone. Nature, 1981, 292(5821): 333-335. DOI:10.1038/292333a0 |

| 35 |

Delwiche C C, Steyn P L. Nitrogen isotope fractionation in soils and microbial reactions. Environmental Science & Technology, 1970, 4(11): 929-935. |

| 36 |

Virginia R A, Delwiche C C. Natural 15N abundance of presumed N2-fixing and non-N2-fixing plants from selected ecosystems. Oecologia, 1982, 54(3): 317-325. DOI:10.1007/BF00380000 |

| 37 |

Schoeninger M J, DeNiro M J. Nitrogen and carbon isotopic composition of bone collagen from marine and terrestrial animals. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1984, 48(4): 625-639. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(84)90091-7 |

| 38 |

Shearer G, Kohl D H. N2-fixation in field settings:Estimations based on natural 15N abundance. Functional Plant Biology, 1986, 13(6): 699-756. |

| 39 |

Kohl D H, Shearer G. Isotopic fractionation associated with symbiotic N2 fixation and uptake of NO3- by plants. Plant Physiology, 1980, 66(1): 51-56. DOI:10.1104/pp.66.1.51 |

| 40 |

Hedges R E M, Reynard L M. Nitrogen isotopes and the trophic level of humans in archaeology. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007, 34(8): 1240-1251. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.015 |

| 41 |

Ambrose S H. Effects of diet, climate and physiology on nitrogen isotope abundances in terrestrial foodwebs. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1991, 18(3): 293-317. DOI:10.1016/0305-4403(91)90067-Y |

| 42 |

Bogaard A, Heaton T H E, Poulton P, et al. The impact of manuring on nitrogen isotope ratios in cereals:Archaeological implications for reconstruction of diet and crop management practices. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2007, 34(3): 335-343. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2006.04.009 |

| 43 |

Jay M, Richards M P. Diet in the Iron Age cemetery population at Wetwang Slack, East Yorkshire, UK:Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2006, 33(5): 653-662. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2005.09.020 |

| 44 |

Price T D, Blitz J, Burton J, et al. Diagenesis in prehistoric bone:Problems and solutions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1992, 19(5): 513-529. DOI:10.1016/0305-4403(92)90026-Y |

| 45 |

Hedges R E M. Bone diagenesis:An overview of processes. Archaeometry, 2002, 44(3): 319-328. DOI:10.1111/arch.2002.44.issue-3 |

| 46 |

王宁, 胡耀武, 宋国定, 等. 古骨中可溶性、不可溶性胶原蛋白的氨基酸组成和C、N稳定同位素比较分析. 第四纪研究, 2014, 34(1): 204-211. Wang Ning, Hu Yaowu, Song Guoding, et al. Comparative analyses of amino acids and C, N stable isotopes between soluble collagen and insoluble collagen within archaeological bones. Quaternary Sciences, 2014, 34(1): 204-211. |

| 47 |

Ambrose S H. Preparation and characterization of bone and tooth collagen for isotopic analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1990, 17(4): 431-451. DOI:10.1016/0305-4403(90)90007-R |

| 48 |

van Klinken G J. Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1999, 26(6): 687-695. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1998.0385 |

| 49 |

鹿化煜, 张红艳, 曾琳, 等. 温度影响东北地区更新世植被变化的黄土记录. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(4): 828-836. Lu Huayu, Zhang Hongyan, Zeng Lin, et al. Temperature forced vegetation variations in glacial interglacial cycles in Northeastern China revealed by loess paleosol deposit. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(4): 828-836. |

| 50 |

刘强, 刘嘉麒, 陈晓雨, 等. 18.5ka B.P.以来东北四海龙湾玛珥湖全岩有机碳同位素记录及其古气候环境意义. 第四纪研究, 2005, 25(6): 711-721. Liu Qiang, Liu Jiaqi, Chen Xiaoyu, et al. Stable carbon isotope record of bulk organic matter from the Sihailongwan Maar Lake, Northeast China during the past 18.5ka. Quaternary Sciences, 2005, 25(6): 711-721. |

| 51 |

孙建中, 王淑英, 王雨灼, 等. 东北末次冰期的古环境. 第四纪研究, 1985(1): 82-89. Sun Jianzhong, Wang Shuying, Wang Yuzhuo, et al. Paleoenvironment of the Last Glacial stage in Northeast China. Quaternary Sciences, 1985(1): 82-89. |

| 52 |

游海涛, 刘嘉麒. 14ka BP以来二龙湾玛珥湖沉积物记录的高分辨率气候演变. 科学通报, 2012, 57(24): 2322-2329. You Haitao, Liu Jiaqi. High-resolution climate evolution derived from the sediment records of Erlongwan Maar Lake since 14ka BP. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2012, 57(27): 3610-3616. |

| 53 |

DeNiro M J. Postmortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature, 1985, 317(6040): 806-809. DOI:10.1038/317806a0 |

| 54 |

同号文, 王晓敏, 陈曦. 吉林乾安大布苏晚更新世野牛化石. 人类学学报, 2013, 32(4): 485-502. Tong Haowen, Wang Xiaomin, Chen Xi. Late Pleistocene Bison priscus from Dabusu in Qian'an County, Jilin, China. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2013, 32(4): 485-502. |

| 55 |

Dufour E, Bocherens H, Mariotti A. Palaeodietary implications of isotopic variability in Eurasian lacustrine fish. Journal of Archaeological Science, 1999, 26(6): 617-627. DOI:10.1006/jasc.1998.0379 |

| 56 |

Hu Y W, Shang H, Tong H W, et al. Stable isotope dietary analysis of the Tianyuan 1 early modern human. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesof the United States of America, 2009, 106(27): 10971-10974. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0904826106 |

| 57 |

Schwartz-Narbonne R, Longstaffe F J, Metcalfe J Z, et al. Solving the woolly mammoth conundrum:Amino acid 15N-enrichment suggests a distinct forage or habitat. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 9791. DOI:10.1038/srep09791 |

| 58 |

Britton K, Müldner G, Bell M. Stable isotope evidence for salt-marsh grazing in the Bronze Age Severn Estuary, UK:Implications for palaeodietary analysis at coastal sites. Journal of Archaeological Science, 2008, 35(8): 2111-2118. DOI:10.1016/j.jas.2008.01.012 |

| 59 |

Clauss M, Steinmetz H, Eulenberger U, et al. Observations on the length of the intestinal tract of African Loxodonta africana, (Blumenbach 1797) and Asian elephants Elephas maximus(Linné 1735). European Journal of Wildlife Research, 2007, 53(1): 68-72. DOI:10.1007/s10344-006-0064-0 |

| 60 |

Clauss M, Hummel J. The digestive performance of mammalian herbivores:Why big may not be that much better. Mammal Review, 2005, 35(2): 174-187. DOI:10.1111/mam.2005.35.issue-2 |

| 61 |

Bocherens H, Drucker D G, Germonpré M, et al. Reconstruction of the Gravettian food-web at Předmostí I using multi-isotopic tracking(13C, 15N, 34S)of bone collagen. Quaternary International, 2014, 359-360(3): 211-228. |

| 62 |

Leggett K. Coprophagy and unusual thermoregulatory behaviour in desert-dwelling elephants of north-western Namibia. Pachyderm, 2004, 36: 113-115. |

| 63 |

Geel B V, Aptroot A, Baittinger C, et al. The ecological implications of a Yakutian mammoth's last meal. Quaternary Research, 2008, 69(3): 361-376. DOI:10.1016/j.yqres.2008.02.004 |

| 64 |

Geel B V, Guthrie R D, Altmann J G, et al. Mycological evidence of coprophagy from the feces of an Alaskan Late Glacial mammoth. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2011, 30(17): 2289-2303. |

| 65 |

Metcalfe J Z, Longstaffe F J, Hodgins G. Proboscideans and paleoenvironments of the Pleistocene Great Lakes:Landscape, vegetation, and stable isotopes. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2013, 76(451): 102-113. |

| 66 |

Lister A M, Stuart A J. The impact of climate change on large mammal distribution and extinction:Evidence from the last glacial/interglacial transition. Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 2008, 340(9): 615-620. |

| 67 |

Kuzmin Y V. Extinction of the woolly mammoth(Mammuthus primigenius)and woolly rhinoceros(Coelodonta antiquitatis)in Eurasia:Review of chronological and environmental issues. Boreas, 2010, 39(2): 247-261. DOI:10.1111/bor.2010.39.issue-2 |

| 68 |

Ukkonen P, Aaris-Sørensen K, Arppe L, et al. Woolly mammoth(Mammuthus primigenius Blum.)and its environment in northern Europe during the Last Glaciation. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2011, 30(5): 693-712. |

| 69 |

Macdonald G M, Beilman D W, Kuzmin Y V, et al. Pattern of extinction of the woolly mammoth in Beringia. Nature Communications, 2011, 3(2): 893-900. |

| 70 |

Stuart A J. The extinction of woolly mammoth(Mammuthus primigenius)and straight-tusked elephant(Palaeoloxodon antiquus)in Europe. Quaternary International, 2005, 126-128(1): 171-177. |

| 71 |

Bocherens H, Billiou D, Patou-Mathis M, et al. Paleobiological implications of the isotopic signatures(13C, 15N) of fossil mammal collagen in Scladina Cave(Sclayn, Belgium). Quaternary Research, 1997, 48(3): 370-380. DOI:10.1006/qres.1997.1927 |

| 72 |

Drucker D G, Bocherens H, Péan S. Isotopes stables(13C, 15N) du collagène des mammouths de Mezhyrich(Epigravettien, Ukraine):Implications paléoécologiques. I'Anthropologie, 2014, 118(5): 504-517. DOI:10.1016/j.anthro.2014.04.001 |

| 73 |

Bocherens H, Fizet M, Mariotti F, et al. Contribution of isotopic biogeochemistry(13C, 15N, 18O)to the paleoecology of mammoths(Mammuthus primigenius). Historical Biology, 1994, 7(3): 187-202. DOI:10.1080/10292389409380453 |

| 74 |

Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, et al. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65Ma to present. Science, 2001, 292(5517): 686-693. DOI:10.1126/science.1059412 |

| 75 |

Kleiven H F, Jansen E, Fronval T, et al. Intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciations in the circum Atlantic region(3.5~2.4Ma)——Ice-rafted detritus evidence. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2002, 184(3-4): 213-223. DOI:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00407-2 |

| 76 |

Thierens M, Pirlet H, Colin C, et al. Ice-rafting from the British-Irish ice sheet since the Earliest Pleistocene(2.6 million years ago):Implications for long-term mid-latitudinal ice-sheet growth in the North Atlantic region. Quaternary Science Reviews, 2012, 44(4): 229-240. |

| 77 |

黄恩清. 中更新世以来东亚冬季风海陆记录对比. 第四纪研究, 2015, 35(6): 1331-1341. Huang Enqing. A comparison of the East Asian winter monsoon reconstructions from terrestrial and marine sedimentary records since the Mid-Pleistocene. Quaternary Sciences, 2015, 35(6): 1331-1341. |

② Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, School of Humanities, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049;

③ Daqing Museum, Daqing 163316)

Abstract

Mammuthus primigenius(woolly mammoth), is the most characteristic mammal in Late Pleistocene, with an extensive Holarctic distribution. The foraging ecology of Mammuthus primigenius plays a significant role in their evolution history and even extinction. Until now, large amounts of researches on diet and ecology using stable isotope had been applied on the Mammuthus primigenius, but the data from East Asia was meagre. Daqing Museum is located in Daqing City, Heilongjiang Province, China(46°58'N, 125°15'E), which is famous for abundant Quaternary mammal fossils, especially Mammoth Fauna in Late Pleistocene. All the samples in this study are collected from sites around Daqing City, though precise sites and layers are not clear. Based on faunal assemblage, the age of these samples is currently estimated to be 40~10ka. In this study, stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis is applied to 33 animal remains, from 9 species, including as Mammuthus primigenius, Coelodonta antiquitatis, Equus przewalskii, Bovidae, Cervidae, Ursus arctos, Felis sp. and Vulpes vulpes. Except for Felis sp., all animals in this study are fed on pure C3 diet. Mammuthus primigenius in this study shows highest δ15N values(10.4±1.3‰, n=6), much higher than other herbivores(represented by Equus przewalskii and Cervidae, 5.8±1.1‰, n=9) even carnivorans(represented by Ursus arctos and Felis sp., 9.4±1.0‰, n=6). Coelodonta antiquitatis(n=3) and Bovidae(n=5) also show relatively higher δ15N values, which are averaged by 7.6±2.5‰ and 8.1±1.9‰, some individuals are even similar to Mammuthus primigenius. Coelodonta antiquitatis and Bovidae have various food resource, partly overlapped with Mammuthus primigenius. Besides, δ13C values of Mammuthus primigenius are lowest among all the fauna(-21.6±0.3‰, n=6). Therefore, Mammuthus primigenius apparently shows specialized foraging behavior compared to other mammals, which may be influenced by three factors, including foraging habitat, physiology and coprophagy. We further collect previously published carbon and nitrogen results from Eastern Europe, Siberia and North America. The data show that Mammuthus primigenius has the highest δ15N values, and relatively lower δ13C values compared to coexisting herbivores(Coelodonta antiquitatis, Equidae, Bovidae and Cervidae). The carbon and nitrogen isotopic data of Mammuthus primigenius represent a stable but narrow dietary breadth, also imply that they may occupy a solid and limited ecological niche. Therefore, a specialized diet and high sensitivity to environmental fluctuations of Mammuthus primigenius at the end of the Last Ice Age might be one of the mainspring of their extinction. 2017, Vol.37

2017, Vol.37