赤铁矿(α-Fe2O3)是自然界中相对稳定的铁氧化物,分布十分广泛,如陆上的红层[1~3]、 黄土/古土壤[4~7]、 海洋粉尘沉积物[8~10]以及大洋红层等[11, 12],记录了丰富的古气候和古地磁信息。赤铁矿在火星上也广泛分布,是火星颜色的主要载体[13~15]。因此,赤铁矿对古气候、 古地磁以及比较行星学的研究都具有十分重要的作用。

赤铁矿是一种反铁磁性矿物,由于晶格内的自旋倾斜和缺陷导致其具有一定的弱亚铁磁性。尽管其饱和磁化强度(0.4Am2/kg)为磁铁矿(92Am2/kg)的约1/200,但是其对自然环境的磁学贡献不容忽视[16~19]。另外,赤铁矿的尼尔(Néel)温度(TN)(675℃)和矫顽力较高,后期成岩过程中地磁场和温度的变化很难影响赤铁矿的剩磁,所以赤铁矿是十分稳定的载磁矿物之一,对古地磁研究具有十分重要的意义[20, 21]。由于赤铁矿对周围环境十分敏感,如温暖干燥的气候有利于赤铁矿的生成,因此与其有关的参数可以作为研究古环境变化的指标[22~24]。

自然界中赤铁矿的形成有多种途径,如Fe3+溶液的水解、 磁铁矿等亚铁磁性矿物低温氧化以及铁氢氧化物的高温脱水[24]。Barrón和Torrent[25]在实验室中模拟赤铁矿的生长过程,提出在磷酸等配位基的作用下,Fe3+溶液中首先形成的是赤铁矿的先驱矿物—非结晶的二线水铁矿,在后期的陈化过程中逐渐形成过渡产物类磁赤铁矿,最终形成赤铁矿,因此他们提出了水铁矿→类磁赤铁矿→赤铁矿的形成途径。在后期的研究中,Michel等[26]和Liu等[27]对该过程中的矿物进行动态磁学测量,进一步证实了该转化机制,同时Michel等[26]提出过渡产物并非类磁赤铁矿,而是亚铁磁性的水铁矿。后来Torrent等[28]结合磁学和漫反射光谱学方法,对土壤样品进行了系统研究,进一步证实该转化机制; 同时,该转化机制受控于溶液酸碱度和温度的影响,一般偏酸或偏碱(pH值为2~4或10~14)的环境比较容易形成针铁矿,而偏中性的环境(pH≈7)较容易形成赤铁矿[29~31]。低温更适合于针铁矿形成,而高温有助于赤铁矿形成[24]。

另外,在低温氧化环境下,强磁性的磁铁矿或磁赤铁矿也会慢慢氧化成赤铁矿,导致样品磁性减弱[32~34],该成因赤铁矿在黄土/古土壤和海底玄武岩中大量存在,但是氧化程度受控于颗粒的粒径和周围环境[35~37]。其次,自然界中的铁水化合物(如纤铁矿、 针铁矿等)在长期的干旱环境中或者高温环境下(如森林火等),可以脱水转化为磁赤铁矿并进一步转化为赤铁矿[38~42]。zdemir和Dunlop[43]在实验室内系统研究了纤铁矿在加热过程中的矿物转化机制,并探讨了该过程中磁性的变化; Jiang等[44]对针铁矿高温脱水产生的赤铁矿进行了系统研究,并提出该类赤铁矿的结晶度比水溶液中形成的赤铁矿结晶度高,但是磁性明显比后者弱; Xie等[37]利用高分辨透射电子显微镜技术在黄土/古土壤中发现了包被在针铁矿边缘的由针铁矿脱水转化形成的赤铁矿。不同成因的赤铁矿所记录的环境信息不同,因此寻找合适的替代性指标,对不同来源的赤铁矿进行有效的定量与半定量化研究,对土壤或沉积物记录的古气候研究具有重要意义。

随着现代科学技术的发展,尤其是光谱分析技术和磁测技术的功能、 精度不断提高,人们对赤铁矿的研究越来越深入,也为赤铁矿的定量化提供了一种可能。利用X射线衍射(X Ray Diffraction,简称XRD)、 穆斯鲍尔谱(Mssbauer Spectrosopy)、 漫反射光谱(Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy,简称DRS)、 磁学等手段,可以鉴别赤铁矿的存在,并根据检测的赤铁矿性质变化,对其进行定量与半定量化研究。

2 赤铁矿定量化的方法及其存在的问题 2.1 磁学指标 2.1.1 硬饱和剩磁(HIRM)和S-ratio作为反铁磁性矿物,相比于磁铁矿或磁赤铁矿等强磁性矿物,赤铁矿磁性太弱,很难单纯利用全样的磁性参数(如磁化率、 饱和等温剩磁SIRM等)来对样品中的赤铁矿进行定量化。如何将赤铁矿的信息从全样信息中提取出来是对样品中赤铁矿进行定量化研究的关键。由于赤铁矿具有极高矫顽力(可高达1 T),一般磁学手段很难使其达到完全饱和,而其他强磁性矿物的矫顽力较低,从几mT到几十mT不等。因此,这种明显的矫顽力差异是提取赤铁矿信息很好的突破口。Collinson[45]对红层样品的岩石磁学研究(尤其是IRM获得曲线测量)发现,外加磁场高于300mT的剩磁贡献主要来源于赤铁矿; 基于此,Robinson[46]认为对获得SIRM的样品施加300mT的反向直流场,矫顽力低于300mT的剩磁(主要由低矫顽力的磁铁矿、 磁赤铁矿等携带)被偏转过来,而剩余的未被反向的剩磁应该主要是矫顽力高于300mT的高矫顽力矿物的贡献,如赤铁矿。于是,Robinson[46]提出用“硬”饱和剩磁(Hard IRM,即HIRM=0.5×(SIRM+IRM-300mT))来指示样品中高矫顽力矿物(如赤铁矿、 针铁矿等)的绝对含量变化,其中SIRM为样品的饱和等温剩磁,IRM-300mT为对样品施加反向300mT直流场后的剩磁。同时,前人根据这个思路,提出了另外一个用来求取赤铁矿等高矫顽力矿物相对含量的一个参数,即S-ratio,利用SIRM对IRM-300mT进行归一化后的值,-IRM-300mT/SIRM,或者更为复杂的一个表示是[(-IRM-300mT/SIRM)+1]/2[47]。当S-ratio值小于0.5甚至为负值时,表示样品中高矫顽力矿物占主导。尽管在这个过程中300mT的选取存在一定的随机性,赤铁矿的部分剩磁可能被退掉,但是这并不影响利用HIRM和S-ratio对剖面序列中的高矫顽力矿物进行半定量化。该参数提出之后,很快在黄土/古土壤[48~52]、 湖泊沉积物[53~55]以及海洋沉积物[9, 10, 56~58]和红土研究[59, 60]中得到了广泛应用。

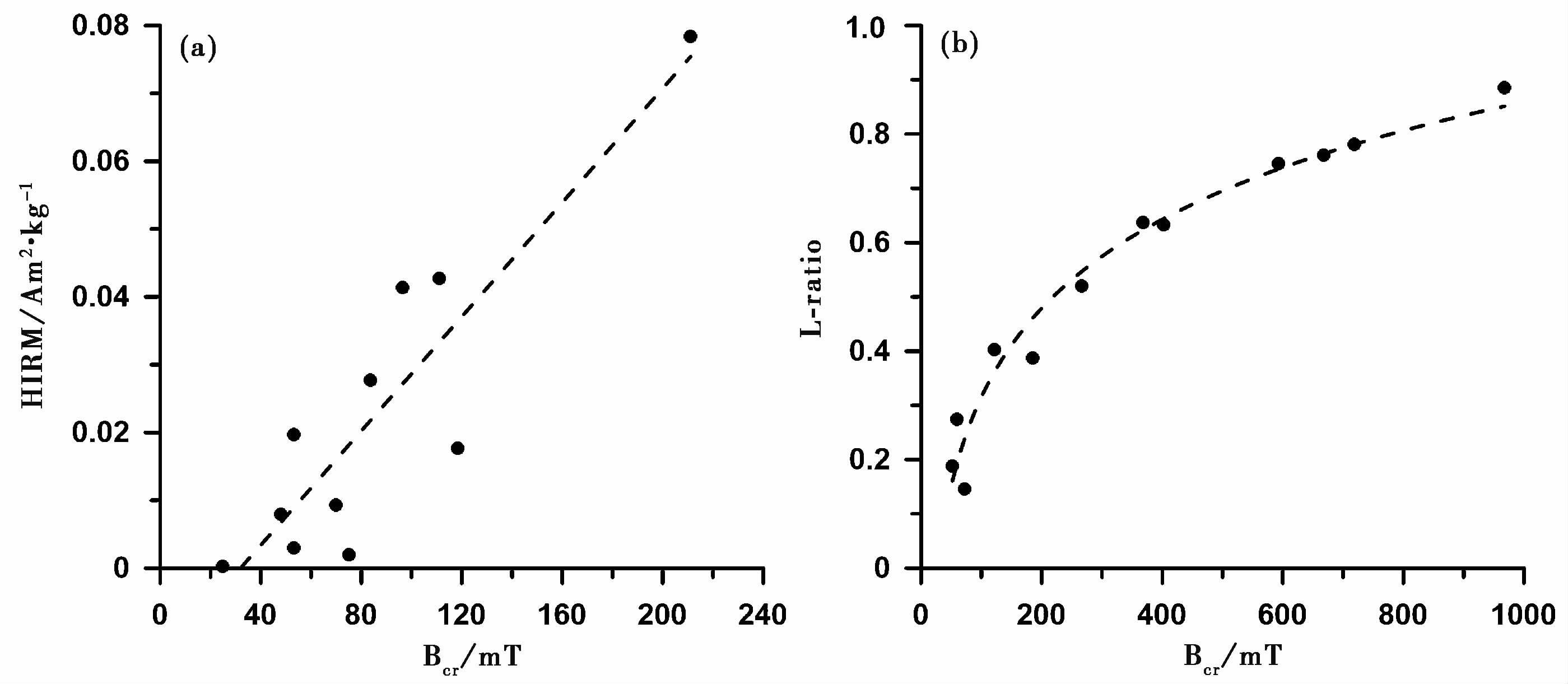

HIRM和S-ratio测量简单,对于长岩芯或者离散样品都可以直接在2G超导磁力仪上进行SIRM和IRM-300mT的测量,方便快捷,是研究长剖面序列中高矫顽力矿物含量变化的良好指标。但是,该参数提出的基本假设是赤铁矿和针铁矿的饱和场都大于300mT,因此在计算时,强磁性矿物(如磁铁矿或磁赤铁矿)的贡献可以抵消[46]。但是赤铁矿和针铁矿的矫顽力受粒径、 离子替代等因素的影响[44, 61~64],从几十到几百mT不等,因此实际样品中二者的矫顽力应该存在一个分布范围。这时候,HIRM受二者含量和矫顽力的双重影响(图 1a),不能很好地反映样品中赤铁矿和针铁矿的含量信息。因此,在利用该参数进行定量化之前,首先需要对样品的矫顽力有个定性的认识。为此,Liu等[65]提出了一个用来衡量矫顽力变化的参数L-ratio,即L-ratio=IRMAF@HmT/IRMAF@LmT,其中IRMAF@HmT和IRMAF@LmT代表分别利用一个高场和低场对SIRM进行交变退(AF),一般选取300mT和100mT。因为100mT的交变场基本上可以将强磁性矿物的信息退掉,所以L-ratio主要反映了反铁磁性矿物的矫顽力分布信息。矫顽力越大,L-ratio越趋于1(图 1b)。当一组样品的L-ratio基本稳定时,HIRM可以用来指示赤铁矿和针铁矿的含量变化。

|

图 1 硬剩磁(HIRM)(a)和L-ratio(b)与剩磁矫顽力(Bcr)的相关图,数据来自文献Liu等[65] Fig. 1 Correlated diagrams of HIRM versus Bcr(a)and L-ratio versus Bcr(b),data referred from Liu et al.[65] |

2.1.2 Mfr和IRMAF@nmT

当样品中强磁性矿物含量很高时,赤铁矿或针铁矿的剩磁信息很容易被强磁性的背景信息完全掩盖,这时候测量的HIRM与测量误差近似,利用HIRM很难精确的反映高矫顽力矿物含量信息。因此,Liu等[66]根据强磁性矿物的矫顽力信息,提出了另外一个可以用来定量化赤铁矿或针铁矿的参数Mfr,即饱和等温剩磁经过磁滞退磁之后的剩余磁化强度。基本测量过程是,首先让样品获得一个饱和等温剩磁,之后根据强磁性矿物的矫顽力信息,利用振动样品磁力仪对其进行逐步的正反向退磁,其中最大的退磁场为强磁性矿物的矫顽力,这样基本上可以把强磁性的信号退掉,剩余的即为高矫顽力的赤铁矿或针铁矿的信号。该参数相比于交变退磁的优点是可以利用很高的场(如1T)对样品进行退磁,而交变退只能退到100mT左右,无法清除100mT以上的强磁性矿物的信号。

Larrasoña等[10]提出了一个与之类似的指标,IRMAF@120mT来对高矫顽力矿物进行定量化。首先给样品施加一个0.9T外场,使其获得IRM,然后利用120mT交变场对其进行交变退,他们认为此时的剩磁应该主要为高矫顽力矿物携带。为了验证该参数的可靠性,其将该参数用于地中海沉积物中记录的撒哈拉粉尘研究。通过对代表性样品的IRMAF@120mT进行热退磁实验,判断该剩磁主要由赤铁矿携带[10]。样品的IRMAF@120mT与HIRM和Ti/Al的变化具有很好的一致性; Ti/Al可以用来指示粉尘输入与河流输入的相对比例,而IRMAF@120mT可以更好的指示粉尘输入[10],因此,通过该指标可以反演粉尘源区撒哈拉沙漠高温干燥的气候变化。

后来,Deng等[4]通过对黄土/古土壤样品的系统研究,进一步提出将SIRMAF@nmT/SIRM作为黄土/古土壤中赤铁矿的相对含量指标,其中SIRMAF@nmT是利用nmT交变场对SIRM进行交变退磁后的剩磁。自晚新生代以来,亚洲内陆进入了一个干旱化的新阶段,深刻影响了全球的环境变化[4, 5]。一个主要特征是在亚洲内陆形成了大量黄土沉积,并且粉尘经西风带搬运进入太平洋,形成了大量粉尘沉积[5, 9]。研究干旱化问题的一个关键是如何从沉积物中获得古气候变化信息。而黄土/古土壤中的赤铁矿含量信息是很好的干旱化指标,低值代表干旱化程度较强。Deng等[4]根据赤铁矿含量参数SIRMAF@nmT/SIRM的变化,推断自晚新生代以来,中国北方的干旱化程度逐渐增强。为晚新生代以来亚洲内陆干旱化提供了一个有效的物理指标。

2.1.3 高场磁化率(xhf)我们在对自然样品进行磁滞回线测量以及数据处理时,基本上直接进行顺磁校正,将高场部分去掉,只提取我们感兴趣的亚铁磁性矿物的信息。Jiang等[61]通过对一系列细粒赤铁矿的高场磁化率进行分析,认为如果能将自然样品的高场磁化率(xhf)信息提取出来,有可能提供一些反铁磁性矿物含量的信息。

Collinson[45]提出可以用磁滞回线的高场磁化率来定性的指示红层样品中赤铁矿的含量。但是,其当时未考虑样品本身含有的顺磁性及抗磁性物质的贡献,如粘土矿物。Brachfeld[67]利用高场磁化率来指示海洋沉积物中顺磁性成分的含量,如海洋生物硅的含量。但是,他们在实验过程中所加外场为1T,样品中的反铁磁性矿物尚未饱和,因此赤铁矿和针铁矿的反铁磁性磁化率对高场部分也有贡献。简言之,高场磁化率是反铁磁性矿物和顺磁性矿物的共同贡献,如下式所示。

|

其中,Na和Np、 xanti和xpara分别代表反铁磁性矿物(赤铁矿、 针铁矿)和顺磁性矿物的相对含量和高场磁化率。因此,直接用xhf来指示反铁磁性矿物或者顺磁性矿物的含量是不合理的。根据前人对(含铝)赤铁矿的反铁磁性磁化率(磁滞回线的高场斜率)[61]以及粘土矿物磁滞性质[68]的研究,我们得到(含铝)赤铁矿的xanti为2.5×10-7~3.5×10-7 m3/kg,而高岭土、 蒙脱石、 绿泥石和伊利石的高场磁化率分别为0.5×10-8 m3/kg、 0.13×10-8 m3/kg、 3.77×10-7 m3/kg和6.28×10-7 m3/kg。显然对于以绿泥石和伊利石为主的自然样品中,由于赤铁矿的含量很低(小于10%),其对xhf的贡献基本可以忽略,如黄土/古土壤中; 但是对于以高岭土和蒙脱石为主要粘土矿物的样品中,如红层样品,赤铁矿和针铁矿对高场磁化率的贡献很大,可以利用xhf来定性指示反铁磁性矿物的含量变化。

为了更精确地计算xhf中赤铁矿的贡献,可以利用柠檬酸-二重碳酸盐-连二亚硫酸盐(citrate-bicarbonate-dithionite,简称CBD)溶解方法对样品中的细粒赤铁矿进行处理[69],测量处理前后的xhf,二者的差值即可作为成土作用赤铁矿的一个定量化指标。

2.1.4 磁学定量化指标存在的问题前人研究表明,赤铁矿/(赤铁矿+针铁矿)(Hm/(Hm+Gt))比值与土壤的母质矿物、 土壤环境以及成土作用持续时间密切相关[70]。赤铁矿和针铁矿形成于两种相反的气候条件下,如前者主要在干热环境中,而后者主要在冷湿环境下形成; 并且这两种矿物十分稳定,可以长期记录气候信息,因此,Hm/(Hm+Gt)是土壤湿度和气候变化的良好指标[22, 71]。

在实际样品中,尤其是黄土/古土壤中,高矫顽力矿物的赤铁矿和针铁矿是伴生的[72],也就是说HIRM等参数反映的是二者的共同信息,因此将二者信息进行有效分离是利用这些参数进行气候研究的关键。

Liu[48]通过对纯的合成针铁矿和赤铁矿的低温测试发现,针铁矿在从室温向低温冷却时,剩磁有明显升高,而对于细粒赤铁矿,其剩磁在该过程中基本稳定,基于此,其提出利用低温下的HIRM-T曲线,计算样品中针铁矿对HIRM的贡献,进而求取两种矿物在室温下的HIRM。该种思路,也可以用于求取针铁矿和赤铁矿对IRMAF@nmT和Mfr的贡献。

2.2 漫反射光谱法由于HIRM等磁学参数反映的是赤铁矿和针铁矿的综合贡献,所以急需新的定量化方法将自然样品中赤铁矿和针铁矿的信息分别提取出来。漫反射光谱(Diffuse Reflectance of Spectroscopy,简称DRS)(可见-近红外范围,约400~2500nm)可以用来对土壤和沉积物中的赤铁矿和针铁矿进行鉴别以及定量化研究[6, 22, 73, 74]。相比于XRD等方法,漫反射光谱的测量精度更高,能够测量的最低含量比值为0.5%[75]。土壤或沉积物的反射包含两个组分,镜面反射和漫反射。当一束光入射到粉末样品的表面时,有一小部分光会直接在表面发生镜面反射,而剩余的光会进入到样品内部,在各个方向发生多次的反射和折射最终有一部分会反射回来,由于反射回来的光不具有方向性,因此称为漫反射[76, 77]。不同颜色的铁氧化物具有不同的反射行为,因此可以利用漫反射光谱对不同的铁氧化物进行鉴别和定量化分析。

2.2.1 红度参数由于不同的铁氧化物颜色存在差异,因此可以根据样品颜色的变化来对其中矿物的含量进行定量化。赤铁矿颜色为红色,根据漫反射光谱得到的红色参数可以用来估计土壤中赤铁矿的含量变化[78]。Torrent等[78, 79]在1980年和1983年分别提出了两个红度参数,即:

|

|

其中,C、 V和H分别指Munsell Chroma、 Value以及Hue的数值,x、 y和Y分别指色度坐标系中的x、 y和色度空间(Cimmission Internationate de L′eclairage,简写CIE)中的亮度。

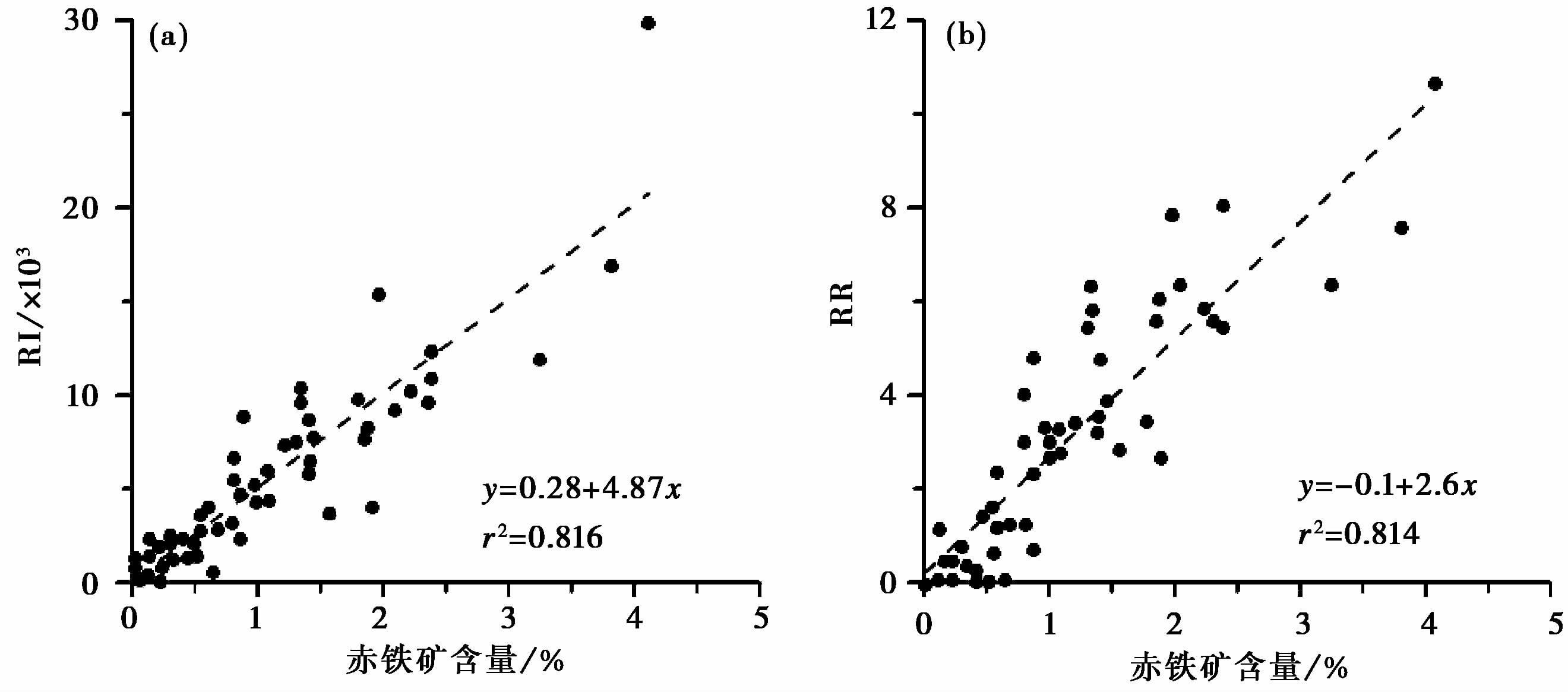

Torrent等[79]利用欧洲土壤样品对这两个红度参数进行了验证,发现其与样品中的赤铁矿含量有很好的线性关系(图 2)。但是对风化程度比较强的巴西土壤的研究发现[79],RI与赤铁矿含量之间的线性关系更为明显,而RR与赤铁矿含量之间没有明显的线性关系。这说明对于同一环境区域的样品,可以用这两个参数进行赤铁矿的定量化,但是不同环境的样品不能进行有效地比较。

|

图 2 欧洲土壤的红度参数与赤铁矿含量的相关关系,修改自Torrent等[79] Fig. 2 Correlation between RI(a),RR (b) and hematite content in soil from Europe,revised from Torrent et al.[79] |

2.2.2 校准方程

根据标准颜色波段可见光可分为6个波段,依次为Vielet=400~450nm; Blue=450~490nm; Green=490~560nm; Yellow=560~590nm; Orange=590~630nm; Red=630~700nm。 各波段的反射率大小是指该波段的反射率占该样品的可见光总反射率(400~700nm的反射率之和,又称亮度)的百分比(%)[80]。

Ji等[7]利用CBD处理过的黄土/古土壤作为基底,合成的赤铁矿和针铁矿为材料,按一定比例混合之后,测量不同混合样品的漫反射光谱,求各波段的反射率。利用逐步多元线性回归方法建立了赤铁矿和针铁矿含量与光谱反射率之间的关系,分别为:

赤铁矿(%)=-1.261-0.0791×Green(%)+0.208×Blue(%)+0.103×Orange(%)-0.0863×Violet(%)(R2=0.985)

针铁矿(%)=-10.6+1.084×Yellow(%)-0.718×Orange(%)+0.34×Red(%)(R2=0.938)

为了验证该标准方程的可靠性,Ji等[7]利用黄土/古土壤剖面进行了验证。指出在古土壤和黄土中针铁矿含量都明显高于赤铁矿,并且黄土/古土壤剖面的赤铁矿/针铁矿比值可以作为反映东亚季风干/湿循环变化的敏感指标,该比值较高时反映了干燥土壤环境,而较低时指示了潮湿土壤环境。该方法在后面的研究中得到了广泛应用[6, 22, 81],但是值得注意的是,因为校准方程是基于黄土和古土壤样品获得的,而检验中的矿物含量范围也是基于黄土/古土壤已知的矿物含量变化,因此该方程只适用于黄土高原的黄土和古土壤,但是这种利用DRS进行赤铁矿和针铁矿定量化的思路可应用于其他类型沉积物和土壤。

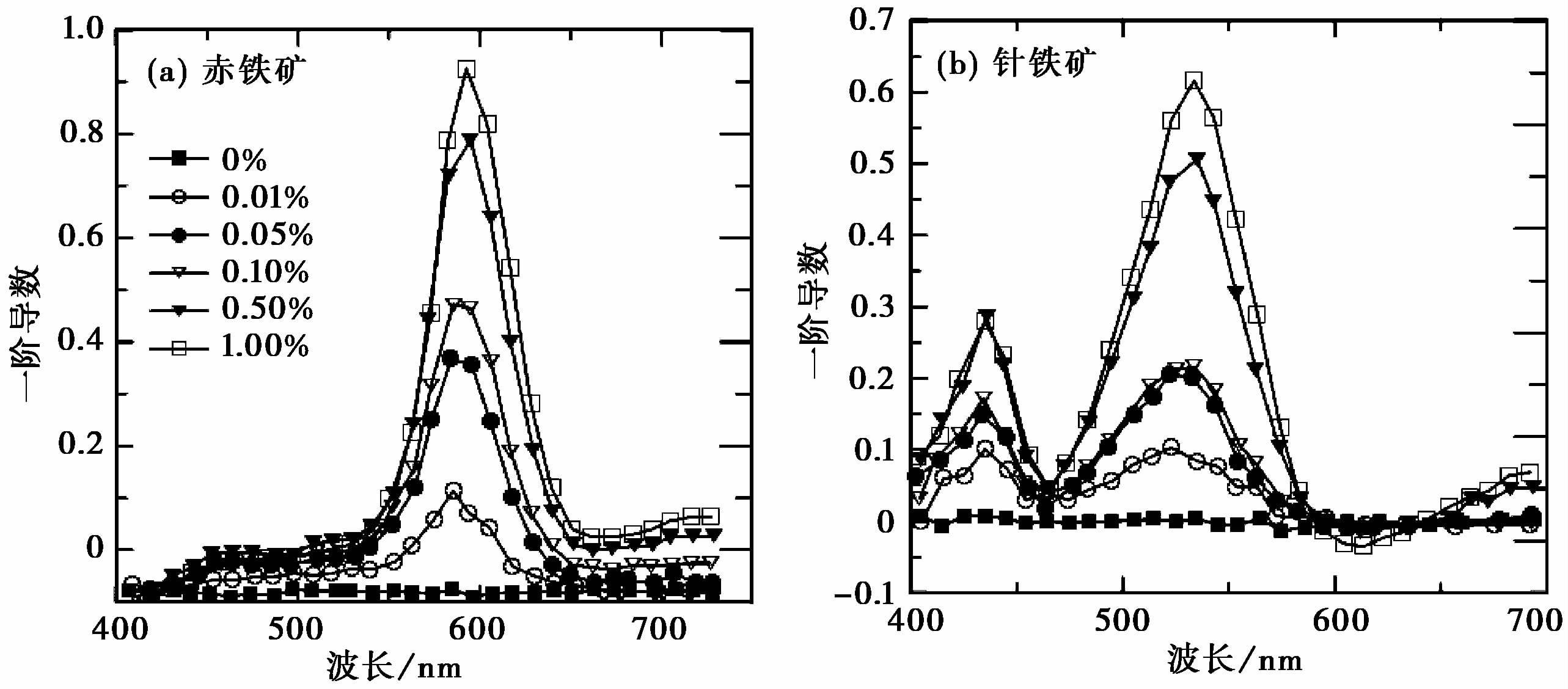

2.2.3 一阶导数特征峰值为了增加计算的精度,Deaton和Balsam[82]提出对初始的漫反射光谱求取一阶导数曲线,利用一阶导数曲线中对应的特征波段强度来计算赤铁矿和针铁矿的含量。从图 3中可以看出赤铁矿在一阶导数曲线中的特征峰位置为565~575nm之间,而针铁矿存在两个特征峰,主峰位置为535nm,而次级峰位置为435nm。随着样品中赤铁矿/针铁矿含量升高,对应的峰强度逐渐增大,因此特征峰强度可以作为样品中赤铁矿和针铁矿的含量指标。

|

图 3 不同赤铁矿和针铁矿含量比例的漫反射光谱的一阶导数曲线,修改自Deaton和Balsam[82] Fig. 3 The first derivative curves of DRS for varying percentage of hematite or goethite mixed with matrix,revised from Deaton and Balsam[82] |

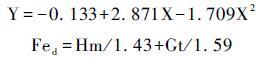

2.2.4 Kubella-Munk(K-M)方程的一阶导数曲线和二阶导数曲线

为了更好的分离反射谱记录的不同矿物信息,可以将原始的漫反射谱数据转化为Kubella-Munk(K-M)函数曲线,然后对该函数求取一阶导数或二阶导数曲线[76],见图 4a和4b(本文未发表的黄土/古土壤数据)。在一阶导数曲线中,赤铁矿和针铁矿的特征谷位置分别在565nm和435nm,而在二阶导数曲线中,二者的特征谷位置分别在535nm和425nm左右[76, 77](图 4c和4d)。因此,利用一阶和二阶导数曲线可以对二者进行有效分离。特征谷与其后相邻峰之间的强度差值(如I425和I535分别用来指示针铁矿和赤铁矿的强度值,图 4d)与赤铁矿和针铁矿含量线性相关[76, 77](图 4e),可以作为二者的定量化指标。如果不求取二者的绝对含量,只是需要含量比值来拟合气候变化趋势的话,可以直接将I425/I535比值作为气候干湿变化的良好指标。后来,人们提出了利用I425和I535来半定量计算土壤中针铁矿和赤铁矿含量的经验公式[73, 83],即:

|

|

图 4 漫反射光谱信息 (a)初始的漫反射光谱,(b)Kubelka-Munk方程F(R)谱,(c)F(R)的一阶导数曲线,(d)F(R)的二阶导数曲线,(e)赤铁矿相对含量与特征谱强度比值的相关图; 其中(a~d)为未发表的黄土/古土壤数据,(e)修改自Torrent和Barrón[76] Fig. 4 The DRS information.(a)The raw data of DRS;(b)Kubelka-Munk function F(R); (c)the first derivative curve of F(R); (d)the second derivative curve of F(R); (e)relationship between Hm/(Hm+Gt)calculated from XRD and the ratio of amplitude of DRS for hematite and goethite, where (e) is revised from Torrent and Barrón[76] |

其中,Y=Hm/(Hm+Gt),X=I535/(I425+I535); 0.07<X<0.4,Hm和Gt分别代表针铁矿和赤铁矿的相对含量,Fed为利用CBD溶解得到的铁含量。该方法被广泛应用到黄土/古土壤、 红粘土和海洋沉积物的研究中[69, 73]。

2.2.5 漫反射光谱法存在的问题利用漫反射光谱法进行赤铁矿定量化存在两个问题: 一个是样品自身基质的颜色会对光谱有很大的影响; 另一个是赤铁矿中的离子替代会对光谱性质产生明显影响[84, 85]。

Deaton和Balsam[82]利用不同基质(如方解石、 石英等)与赤铁矿按不同比例混合,测量其漫反射光谱,发现不同基质对一阶曲线中赤铁矿的峰值强度有明显影响。赤铁矿含量相同的情况下,基质颜色越暗,一阶曲线中赤铁矿的峰值强度越小。因此,在实际样品测量分析过程中要注意基质的影响。对于同一基质的样品,可用该方法对其进行定量化比较。但是对于不同基质的样品,其赤铁矿含量不能相互比较。

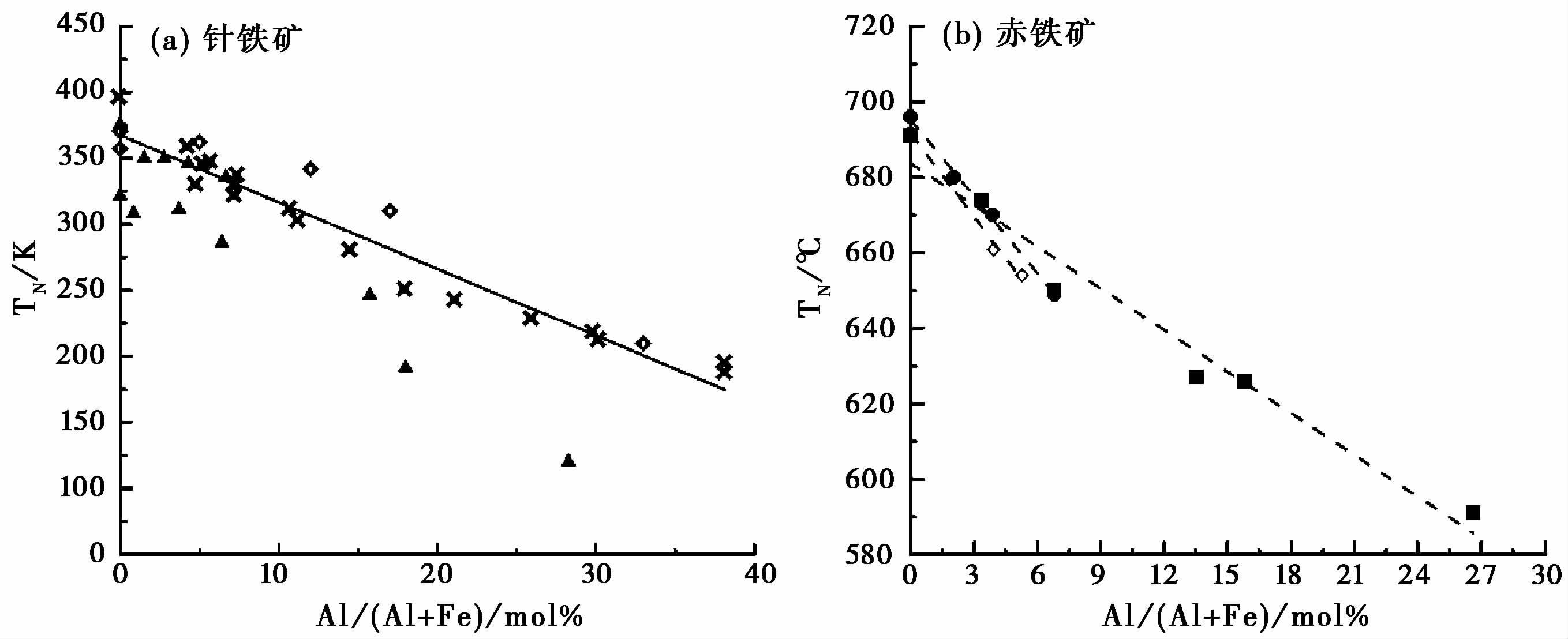

另外,由于前述的公式理论等都是基于纯针铁矿和赤铁矿的基础上建立的,未考虑其他离子替代的影响,所以在应用上仍存在一些多解性和局限性。Liu等[84]和Jiang等[85]的结果表明,针铁矿和赤铁矿的DRS特征峰位置和强度明显受到铝替代量的影响,铝含量的改变可以使DRS强度变化2倍。所以,不考虑铝替代的影响,直接利用经验公式计算天然样品中针铁矿和赤铁矿的含量并不合理,在计算之前最好先检测样品中的铝含量。Jiang等[44, 85]的研究表明,赤铁矿和针铁矿的TN与铝含量呈线性反相关(图 5)。因此,可以利用样品中赤铁矿和针铁矿TN的变化来判断铝含量的变化。

|

图 5 尼尔温度(TN)与铝替代量的相关图 (a)针铁矿,修改自Jiang等[85];(b)赤铁矿,修改自Jiang等[44] Fig. 5 The relationship between TN and Al substitution. (a)For goethite,revised from Jiang et al.[85] and (b) for hematite,revised from Jiang et al.[44] |

3 气候意义探讨 3.1 黄土/古土壤的降雨量研究

由于成土作用产生的赤铁矿主要是通过水铁矿转化而来,因此高温和短期的降水能够促进赤铁矿的形成[86]。与磁铁矿相比,长期的高温干燥环境以及短期的土壤湿润更利于赤铁矿的生长,所以赤铁矿的含量变化可以用来研究与成土相关的环境因素,如降雨量[6, 87]。Balsam等[6]利用漫反射光谱法对黄土/古土壤中赤铁矿进行了定量化研究,并尝试性地利用赤铁矿的含量变化建立了赤铁矿含量与降水量之间的关系模型(图 6a)。

|

图 6 赤铁矿含量与降雨量的相关图 (a)Balsam等[6]的降雨量模型,其中虚线和实线分别代表赤铁矿和磁铁矿;(b)海南岛土壤剖面的赤铁矿含量与降雨量相关图,数据来自Long等[87];(c)海南岛土壤剖面的针铁矿含量与降雨量相关图,数据来自Long等[87] Fig. 6 Correlated diagrams of magnetic minerals concentration and rainfall. (a)The model proposed by Balsam et al.[6],where the dash and solid line represent hematite and magnetite,respectively; (b)the relationship between hematite content and rainfall, data referred from Long et al.[87]; (c)the relationship between goethite content and rainfall,data referred from Long et al.[87] |

他们认为当温度很高,雨季很短不足以产生大量磁铁矿的时候,赤铁矿的含量可以达到最高值。随着雨季增长,赤铁矿含量首先达到稳定水平,之后随着温暖干燥期的缩短赤铁矿含量迅速下降。根据黄土高原的实际降雨量数据,Balsam等[6]认为赤铁矿含量在降雨量为550~600mm/a、 温度在10℃左右时达到峰值,之后随着降雨量增加会逐渐下降; 而磁铁矿在降雨量为650mm/a的时候达到最高值。Long等[87]通过对雨水充沛的海南岛腐殖土剖面的研究进一步验证了该模型的成立。海南的降雨量为1440~2020mm/a,温度变化为23~24℃,风化十分严重。他们发现,随着降雨量的增加,赤铁矿和磁铁矿的含量逐渐降低,而针铁矿的含量升高(图 6b和6c)。这与Balsam等[6]的模型是一致的,降水量为500mm时生成大量的赤铁矿和少量的磁铁矿,降水量为700mm时土壤中磁铁矿和赤铁矿的含量达到最大,此时土壤的磁化率最高; 随着降水量的进一步升高,磁性较强的亚铁磁性矿物(磁铁矿、 磁赤铁矿)转化生成的磁性很弱的针铁矿使得土壤的磁性降低。

3.2 季风变化指标赤铁矿和针铁矿的分布和含量与成土气候环境密切相关[70, 88]。由于土壤中赤铁矿的形成涉及水铁矿的转化以及针铁矿的脱水反应,因此蒸发量大于降雨量的干旱环境有利于赤铁矿的形成,而针铁矿一般是从水溶液中直接沉淀形成,潮湿的环境有利于其发育。这两种矿物的形成是相互竞争的,环境因素控制着它们的形成比例,因此,赤铁矿/针铁矿的比值变化是气候变化的良好指标[71]。

季峻峰等[81]采用漫反射光谱法分析了黄土/古土壤样品中赤铁矿和针铁矿含量变化以及分布特征,发现黄土/古土壤剖面的赤铁矿/针铁矿含量比值(Hm/Gt)可作为东亚季风干/湿变化的敏感指标。该比值与氧同位素具有很好的对应关系[89, 90],较高时反映了干燥土壤环境,而较低时指示了潮湿土壤环境(图 7a和7b)。季峻峰等[81]对灵台和洛川剖面中赤铁矿/针铁矿比值的分析,初步揭示了2.16Ma年以来黄土高原东亚季风阶段性变强的特征。

后来,Zhang等[74, 91]将该指标利用到南海沉积物的研究中。通过对位于中国南海的ODP1143钻孔的沉积物进行系统漫反射光谱测量,得到了相应的赤铁矿/针铁矿比值。该比值与石笋记录的氧同位素信息具有极好的对应关系,可以反映亚洲季风的变化(图 7c和7d); 结合其他参数信息,他们认为在中上新世(4.2~2.7Ma),一个主要特征就是海洋中Ca同位素含量增大(图 7e和7f)。 这表明亚洲季风存在明显增强[91]。

|

图 7 赤铁矿/针铁矿比值(Hm/Gt)的变化趋势与氧同位素的对比 (a)GISP2δ18O记录[89, 90];(b)延长剖面的针铁矿与赤铁矿比值,修改自Ji等[22];(c)南海ODP1143孔沉积物170ka以来的赤铁矿与针铁矿比值[74]; (d)董哥洞和葫芦洞的石笋氧同位素数据,修改自Zhang等[74];(e)南海ODP1143孔沉积物5000ka以来的赤铁矿与针铁矿比值(灰线)[91]; (f)西南太平洋DSDP 590孔沉积物的Ca同位素数据(实心正方形,实线),修改自Zhang等[91] Fig. 7 Comparison δ18O and Hm/Gt records. (a)GISP2δ18O record[89, 90]; (b)Hm/Gt record from Yanchang section,modified from Ji et al.[22]; (c)Hm/Gt record from ODP 1143 in South China for the last 170ka[74]; (d)stalagmite oxygen isotopes from Dongge and Hulu caves,revised from Zhang et al.[74]; (e)Hm/Gt record from ODP1143 in South China for the past 5000ka[91]; (f)δ44Ca from DSDP 590 in Southwest Pacific Ocean for the past 5000ka,revised from Zhang et al.[91] |

3.3 内陆干旱化指标

远洋沉积物所含的赤铁矿一般来源于内陆,可以反映内陆源区的干旱化以及全球粉尘的运输过程[92]。Yamazaki和Ioka[9]对北太平洋的5个远洋沉积物钻孔进行了系统的岩石磁学研究,测量了样品的HIRM和SIRM。发现自2.5Ma以来,样品的HIRM存在明显增加,而SIRM明显减小(图 8)。说明样品中硬磁性组分增加,而强磁性矿物含量减少。由于该时期正好对应着北半球冰期的开始,即黄土沉积的形成时期。因此他们认为2.5Ma之后北太平洋的远洋沉积物主要来源是亚洲粉尘的输入,并且其中主要的载磁矿物应该是硬磁性的赤铁矿或针铁矿。所以,HIRM可以作为亚洲粉尘输入,即亚洲内陆干旱化的一个良好替代指标。后来Maher和 Dennis[93]、 Larrasoña等[10]分别利用该指标研究了北大西洋和地中海的粉尘输入信息。

|

图 8 北太平洋远洋沉积物钻孔的饱和等温剩磁(SIRM)和硬饱和剩磁(HIRM)随年龄的变化趋势,数据来自Yamazaki和Ioka[9] Fig. 8 Saturation isothermal remanent magnetization(SIRM)(solid squares)and hard IRM(HIRM)(open squares) ersus age of pelagic-clay cores in the North Pacific Ocean,data from Yamazaki and Ioka[9] |

3.4 海洋沉积物定年手段

地质年代的精确界定是我们认识地球演化历史和过程的关键,利用天文旋回理论进行地质定年的方法是地层学解读时间的一个里程碑。应用旋回理论,通过对高分辨率的旋回记录进行天文调谐来建立天文年代标尺,已成为现代地质学研究的一个亮点[94]。可以反映古气候旋回变化的参数,如赤铁矿含量可以很好的反映气候变化信息,其变化曲线已被广泛用于旋回定年中,尤其是海洋沉积物的研究[95, 96]。

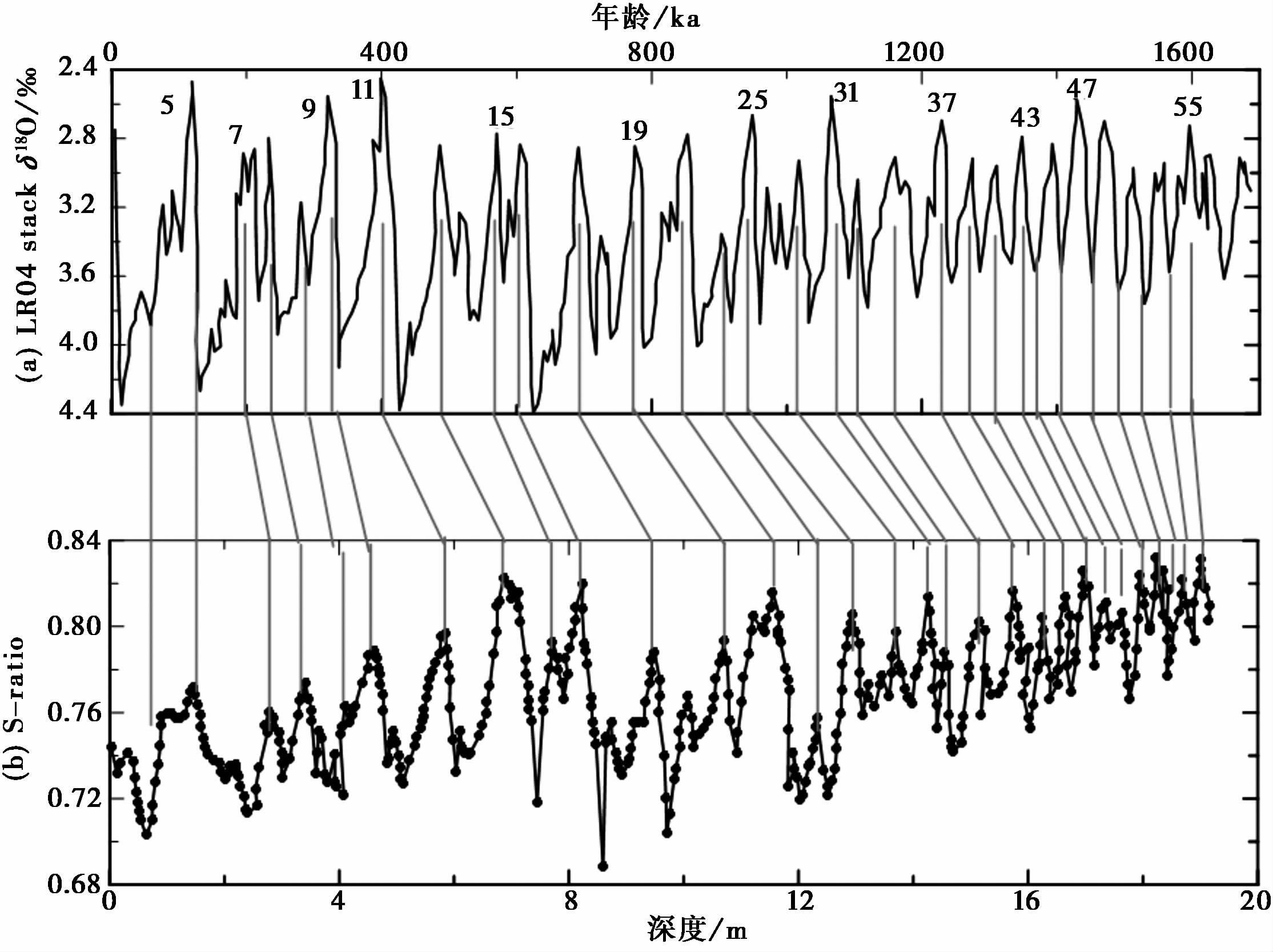

Yamazaki和Kanamatsu[96]在对北太平洋沉积物的研究中,发现单纯利用氧同位素信息不能直接对该孔沉积物进行年代控制,因为钻孔位于碳酸盐补偿深度(CCD)之下,几乎没有碳酸盐保存下来。而S-ratio可以很好的反映冰期间冰期的变化,因此,其将S-ratio与氧同位素数据进行了调谐,二者具有很好的一致性,得到沉积物的年龄为0~1.6Ma,旋回周期为40ka(图 9)。后来,Ao等[95]对南海ODP1143孔沉积物5Ma以来的 Hm/Gt 记录和氧同位素进行了天文调谐,为该孔提供了新的年龄标尺。

|

图 9 KR0310-PC1孔的年龄控制,其中S-ratio的变化与全球氧同位素基本对应,引自Yamazaki和Kanamatsu[96] Fig. 9 Age control of KR0310-PC1. Variations of S-ratio are correlated to the global oxygen isotope(δ18O) stack at horizons indicated by tie lines,referred from Yamazaki and Kanamatsu[96] |

4 小结

赤铁矿是土壤和沉积物中主要的铁氧化物,其含量变化具有重要的环境和气候意义。但对其进行有效的定量化一直是个难题,一是由于相对于粘土矿物等基质,磁性矿物在土壤中的含量很低,很难用常规方法对其进行定量化测量; 另一个是其磁性较弱,很容易被强磁性矿物的信息所掩盖。但是,赤铁矿的特征是矫顽力高,颜色为红色,具有较强的染色能力。将其作为突破口,前人提出了一系列对其进行定量化的参数。

由于赤铁矿的矫顽力较高,而强磁性矿物(如磁铁矿等)矫顽力较低,因此可调节外加磁场的大小将不同矫顽力矿物对剩磁的贡献进行有效区分。基于此,他们提出了HIRM、 IRMAF@nmT、 Mfr等磁学定量化指标。但是,由于针铁矿也是高矫顽力矿物,因此在利用这些参数对赤铁矿进行定量化的时候,很容易将针铁矿的信息混淆进去。所以,在利用这些参数对赤铁矿进行定量化时,首先对样品中的矿物成分进行鉴定,如果有针铁矿的存在,要对其贡献有个定量化的认识。

另外,基于赤铁矿的颜色特征,前人利用漫反射光谱法对其进行了系统研究,提出了一系列的定量化指标,如红度参数、 经验公式、 校准方程等。但是该系列参数不仅受矿物含量的影响,而且样品基质和离子替代等都会影响测量的赤铁矿含量值。因此,利用该参数时,需要考虑这两个因素的影响。通过将磁学方法与漫反射光谱结合,可以解决离子替代的影响,分别对这两种矿物进行有效定量化。基于天然样品的复杂性,对上述定量化方法的可靠性还需要深入研究,为气候变化提供更强有力的替代性指标。

致谢: 感谢本期特邀编审吴海斌研究员的邀请,感谢审稿人的宝贵意见。

| 1 |

Walker T R. Color of recent sediments in tropical Mexico:A contribution to the origin of red beds[J].

Bulletin of the Geological Society of America,1967, 78 (7) : 917~920.

( 0) 0)

|

| 2 |

Walker T R. Formation of red beds in modern and ancient deserts[J].

Geological Society of America Bulletin,1967, 78 (3) : 353~368.

( 0) 0)

|

| 3 |

Walker T R, Larson E E, Hoblitt R P. Nature and origin of hematite in the Moenkopi Formation(Triassic), Colorado Plateau:A Contribution to the origin of magnetism in red beds[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,1981, 86 (B1) : 317~333.

( 0) 0)

|

| 4 |

Deng C, Shaw J, Liu Q, et al. Mineral magnetic variation of the Jingbian loess/paleosol sequence in the northern Loess Plateau of China:Implications for Quaternary development of Asian aridification and cooling[J].

Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2006, 241 (1) : 248~259.

( 0) 0)

|

| 5 |

邓成龙, 刘青松, 潘永信, 等. 中国黄土环境磁学[J].

第四纪研究,2007, 27 (2) : 193~209.

Deng Chenglong, Liu Qingsong, Pan Yongxin, et al. Environmental magnetism of Chinese loess-paleosol sequences[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2007, 27 (2) : 193~209. (  0) 0)

|

| 6 |

Balsam W, Ji J, Chen J. Climatic interpretation of the Luochuan and Lingtai loess sections, China, based on changing iron oxide mineralogy and magnetic susceptibility[J].

Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2004, 223 (3) : 335~348.

( 0) 0)

|

| 7 |

Ji J, Balsam W, Chen J, et al. Rapid and quantitative measurement of hematite and goethite in the Chinese loess-paleosol sequence by diffuse reflectance spectroscopy[J].

Clays and Clay Minerals,2002, 50 (2) : 208~216.

( 0) 0)

|

| 8 |

Jiang Zhaoxia, Liu Qingsong. Magnetic characterization and paleoclimatic significances of Late Pliocene-Early Pleistocene sediments at site 882A, northwestern Pacific Ocean[J].

Science China:Earth Science,2012, 55 (2) : 323~331.

( 0) 0)

|

| 9 |

Yamazaki T, Ioka N. Environmental rock-magnetism of pelagic clay:Implications for Asian eolian input to the North Pacific since the Pliocene[J].

Paleoceanography,1997, 12 (1) : 111~124.

( 0) 0)

|

| 10 |

Larrasoaña J, Roberts A, Rohling E, et al. Three million years of monsoon variability over the northern Sahara[J].

Climate Dynamics,2003, 21 (7) : 689~698.

( 0) 0)

|

| 11 |

Hu X, Jansa L, Wang C, et al. Upper Cretaceous oceanic red beds(CORBs)in the Tethys:Occurrences, lithofacies, age, and environments[J].

Cretaceous Research,2005, 26 (1) : 3~20.

( 0) 0)

|

| 12 |

Wang C, Hu X, Sarti M, et al. Upper Cretaceous oceanic red beds in southern Tibet:A major change from anoxic to oxic, deep-sea environments[J].

Cretaceous Research,2005, 26 (1) : 21~32.

( 0) 0)

|

| 13 |

Christensen P R, Bandfield J L, Clark R N, et al. Detection of crystalline hematite mineralization on Mars by the Thermal Emission Spectrometer:Evidence for near-surface water[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2000, 105 (E4) : 9623~9642.

( 0) 0)

|

| 14 |

Christensen P R, Morris R V, Lane M D, et al. Global mapping of Martian hematite mineral deposits:Remnants of water-driven processes on early Mars[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2001, 106 (E10) : 23873~23885.

( 0) 0)

|

| 15 |

Dunlop D J, Arkani-Hamed J. Magnetic minerals in the Martian crust[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2005, 110 .

doi: 10.1029/2005JE002404 ( 0) 0)

|

| 16 |

Dunlop D J, Özdemir Ö.

Rock Magnetism:Fundamentals and Frontiers[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001 : 1 ~573.

( 0) 0)

|

| 17 |

Morrish A.

Canted Antiferromagnetism:Hematite[M]. Singapore: World Scientific Pub Co Pte. Ltd, 1994 : 51 ~76.

( 0) 0)

|

| 18 |

O'Reilly W.

Rock and Mineral Magnetism[M]. Glasgow: Blackie & Son Ltd, 1984 : 172 ~186.

( 0) 0)

|

| 19 |

Liu Q, Roberts A P, Larrasoaña J C, et al. Environmental magnetism:Principles and applications[J].

Reviews of Geophysics,2012, 50 (4) .

doi: 10.1029/2012RG000393 ( 0) 0)

|

| 20 |

Zhu R X, Potts R, Pan Y X, et al. Paleomagnetism of the Yuanmou basin near the southeastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau and its constraints on Late Neogene sedimentation and tectonic rotation[J].

Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2008, 272 (1-2) : 97~104.

( 0) 0)

|

| 21 |

Tan X, Kodama K P, Wang P, et al. Palaeomagnetism of Early Triassic limestones from the Huanan Block, South China:No evidence for separation between the Huanan and Yangtze blocks during the Early Mesozoic[J].

Geophysical Journal International,2000, 142 (1) : 241~256.

( 0) 0)

|

| 22 |

Ji J, Chen J, Balsam W, et al. High resolution hematite/goethite records from Chinese loess sequences for the last glacial-interglacial cycle:Rapid climatic response of the East Asian monsoon to the tropical Pacific[J].

Geophysical Research Letters,2004, 31 .

doi: 10.1029/2003GL018975 ( 0) 0)

|

| 23 |

Thompson R, Oldfield F.

Environmental Magnetism[M]. London: Allen und Unwin, 1986 : 1 ~227.

( 0) 0)

|

| 24 |

Schwertmann U, Cornell R M.

Iron Oxides in the Laboratory[M]. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH, 2000 : 121 ~134.

( 0) 0)

|

| 25 |

Barrón V, Torrent J. Evidence for a simple pathway to maghemite in Earth and Mars soils[J].

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta,2002, 66 (15) : 2801~2806.

( 0) 0)

|

| 26 |

Michel F M, Barrón V, Torrent J, et al. Ordered ferrimagnetic form of ferrihydrite reveals links among structure, composition, and magnetism[J].

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,2010, 107 (7) : 2787~2792.

( 0) 0)

|

| 27 |

Liu Q, Barrón V, Torrent J, et al. Magnetism of intermediate hydromaghemite in the transformation of 2-line ferrihydrite into hematite and its paleoenvironmental implications[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2008, 113 (B1) .

( 0) 0)

|

| 28 |

Torrent J, Barrón V, Liu Q. Magnetic enhancement is linked to and precedes hematite formation in aerobic soil[J].

Geophysical Research Letters,2006, 33 (L2) .

doi: 10.1029/2005GL024818 ( 0) 0)

|

| 29 |

Cudennec Y, Lecerf A. The transformation of ferrihydrite into goethite or hematite, revisited[J].

Journal of Solid State Chemistry,2006, 179 (3) : 716~722.

( 0) 0)

|

| 30 |

Lewis D, Schwertmann U. The effect of on the goethite produced from ferrihydrite under alkaline conditions[J].

Journal of Colloid and Interface Science,1980, 78 (2) : 543~553.

( 0) 0)

|

| 31 |

Schwertmann U, Murad E. Effect of pH on the formation of goethite and hematite from ferrihydrite[J].

Clays and Clay Minerals,1983, 31 (4) : 277~284.

( 0) 0)

|

| 32 |

Swaddle T W, Oltmann P. Kinetics of the magnetite-maghemite-hematite transformation, with special reference to hydrothermal systems[J].

Canadian Journal of Chemistry,1980, 58 (17) : 1763~1772.

( 0) 0)

|

| 33 |

Nasrazadani S, Raman A. The application of infrared spectroscopy to the study of rust systems—Ⅱ. Study of cation deficiency in magnetite(Fe3O4)produced during its transformation to maghemite(γ-Fe2O3)and hematite(α-Fe2O3).[J].

Corrosion Science,1993, 34 (8) : 1355~1365.

( 0) 0)

|

| 34 |

Adnan J, O'Reilly W. The transformation of gamma Fe2O3 to alpha Fe2O3:Thermal activation and the effect of elevated pressure[J].

Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors,1999, 110 (1-2) : 43~50.

( 0) 0)

|

| 35 |

Liu Q, Banerjee S K, Jackson M J, et al. An integrated study of the grain-size-dependent magnetic mineralogy of the Chinese loess/paleosol and its environmental significance[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2003, 108 (B9) : 1~14.

( 0) 0)

|

| 36 |

Liu Q, Banerjee S K, Jackson M J, et al. New insights into partial oxidation model of magnetites and thermal alteration of magnetic mineralogy of the Chinese loess in air[J].

Geophysical Journal International,2004, 158 (2) : 506~14.

( 0) 0)

|

| 37 |

Xie Qiaoqin, Chen Tianhu, Xu Xiaochun, et al. Transformation relationship among different magnetic minerals within loess-paleosol sediments of the Chinese Loess Plateau[J].

Science in China(Series D),2009, 52 (3) : 313~322.

( 0) 0)

|

| 38 |

Fan H, Song B, Li Q. Thermal behavior of goethite during transformation to hematite[J].

Materials Chemistry and Physics,2006, 98 (1) : 148~153.

( 0) 0)

|

| 39 |

Gendler T S, Shcherbakov V P, Dekkers M J, et al. The lepidocrocite-maghemite-haematite reaction chain—Ⅰ. Acquisition of chemical remanent magnetization by maghemite, its magnetic properties and thermal stability[J].

Geophysical Journal International,2005, 160 (3) : 815~832.

( 0) 0)

|

| 40 |

Ruan H D, Gilkes R. Dehydroxylation of aluminous goethite:Unit cell dimensions, crystal size and surface area[J].

Clays and Clay Minerals,1995, 43 (2) : 196~211.

( 0) 0)

|

| 41 |

Ruan H D, Frost R L, Kloprogge J T. The behavior of hydroxyl units of synthetic goethite and its dehydroxylated product hematite[J].

Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy,2001, 57 (13) : 2575~2586.

( 0) 0)

|

| 42 |

Wells M. Formation of corundum and aluminous hematite by thermal dehydroxylation of aluminous goethite[J].

Clay Minerals,1989, 24 (3) : 513~530.

( 0) 0)

|

| 43 |

ÖzdemirÖ, DunlopD J. Chemical remanent magnetization during gamma-FeOOH phase transformations[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,1993, 98 (B3) : 4191~4198.

( 0) 0)

|

| 44 |

Jiang Z, Liu Q, Barrón V, et al. Magnetic discrimination between Al-substituted hematites synthesized by hydrothermal and thermal dehydration methods and its geological significance[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2012, 117 (B2) .

doi: 10.1029/2011JB008605 ( 0) 0)

|

| 45 |

Collinson D. An estimate of the haematite content of sediments by magnetic analysis[J].

Earth and Planetary Science Letters,1968, 4 (6) : 417~421.

( 0) 0)

|

| 46 |

Robinson S G. The Late Pleistocene palaeoclimatic record of North Atlantic deep-sea sediments revealed by mineral-magnetic measurements[J].

Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors,1986, 42 (1) : 22~47.

( 0) 0)

|

| 47 |

Bloemendal J, King J, Hall F, et al. Rock magnetism of Late Neogene and Pleistocene deep-sea sediments:Relationship to sediment source, diagenetic processes, and sediment lithology[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,1992, 97 (B4) : 4361~4375.

( 0) 0)

|

| 48 |

Liu Qingsong.

Pedogenesis and Its Effects on the Natural Remanent Magnetization Acquisition History of the Chinese Loess[M]. Minnesota: The Ph.D.Thesis of University of Minnesota, 2004 : 28 ~36.

( 0) 0)

|

| 49 |

Bloemendal J, Liu X. Rock magnetism and geochemistry of two Plio-Pleistocene Chinese loess-palaeosol sequences-Implications for quantitative palaeoprecipitation reconstruction[J].

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,2005, 226 (1-2) : 149~166.

( 0) 0)

|

| 50 |

Nie J, Song Y, King J W, et al. HIRM variations in the Chinese red-clay sequence:Insights into pedogenesis in the dust source area[J].

Journal of Asian Earth Sciences,2010, 38 (3) : 96~104.

( 0) 0)

|

| 51 |

Hao Q, Oldfield F, Bloemendal J, et al. The record of changing hematite and goethite accumulation over the past 22 Myr on the Chinese Loess Plateau from magnetic measurements and diffuse reflectance spectroscopy[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2009, 114 (B12) : B12101.

( 0) 0)

|

| 52 |

Bloemendal J, Liu X, Sun Y, et al. An assessment of magnetic and geochemical indicators of weathering and pedogenesis at two contrasting sites on the Chinese Loess Plateau[J].

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,2008, 257 (1) : 152~168.

( 0) 0)

|

| 53 |

Geiss C E, Banerjee S K, Camill P, et al. Sediment-magnetic signature of land-use and drought as recorded in lake sediment from south-central Minnesota, USA[J].

Quaternary Research,2004, 62 (2) : 117~125.

( 0) 0)

|

| 54 |

Flower R, Mackay A, Rose N, et al. Sedimentary records of recent environmental change in Lake Baikal, Siberia[J].

The Holocene,1995, 5 (3) : 323~327.

( 0) 0)

|

| 55 |

Dearing J, Boyle J, Appleby P, et al. Magnetic properties of recent sediments in Lake Baikal, Siberia[J].

Journal of Paleolimnology,1998, 20 (2) : 163~173.

( 0) 0)

|

| 56 |

Yamazaki T, Ikehara M. Origin of magnetic mineral concentration variation in the Southern Ocean[J].

Paleoceanography,2012, 27 .

doi: 10.1029/2011PA002271 ( 0) 0)

|

| 57 |

Liu J, Zhu R, Roberts A P, et al. High-resolution analysis of early diagenetic effects on magnetic minerals in post-Middle-Holocene continental shelf sediments from the Korea Strait[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2004, 109 .

doi: 10.1029/2003JB002813 ( 0) 0)

|

| 58 |

王世朋, 李永祥, 付少英, 等. 南海北部陆坡GHE24L柱样沉积物磁性特征及其环境意义[J].

第四纪研究,2014, 34 (3) : 516~527.

Wang Shipeng, Li Yongxiang, Fu Shaoying, et al. Environmental changes as recorded by mineral magnetic properties of sediments from the core GHE24L, South China Sea[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2014, 34 (3) : 516~527. (  0) 0)

|

| 59 |

吉茹, 胡忠行, 张卫国, 等. 浙江金衢盆地界首红土剖面磁性特征及环境意义[J].

第四纪研究,2015, 35 (4) : 1020~1029.

Ji Ru, Hu Zhongxing, Zhang Weiguo, et al. Magnetic properties of the Jieshou red clay sequence in the Jinhua-Quzhou basin, Southeastern China and its paleoenvironmental implications[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2015, 35 (4) : 1020~1029. (  0) 0)

|

| 60 |

吕镔, 刘秀铭, 王涛, 等. 花岗岩上发育的亚热带红土岩石磁学特征[J].

第四纪研究,2014, 34 (3) : 504~514.

Lü Bin, Liu Xiuming, Wang Tao, et al. Rock magnetic properties of subtropical red soils developed on granite[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2014, 34 (3) : 504~514. (  0) 0)

|

| 61 |

Jiang Z, Liu Q, Dekkers M J, et al. Ferro and antiferromagnetism of ultrafine-grained hematite[J].

Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems,2014, 15 (6) : 2699~2712.

( 0) 0)

|

| 62 |

Wells M, Fitzpatrick R, Gilkes R, et al. Magnetic properties of metal-substituted haematite[J].

Geophysical Journal International,1999, 138 (2) : 571~580.

( 0) 0)

|

| 63 |

Banerjee S K. New grain size limits for palaeomagnetic stability in haematite[J].

Nature,1971, 232 (27) : 15~16.

( 0) 0)

|

| 64 |

Chevallier R. Propriétés magnétiques de l'oxyde ferrique rhomboédrique(α-Fe2O3)[J].

Journal of Physics Radium,1951, 12 (3) : 172~188.

( 0) 0)

|

| 65 |

Liu Q, Roberts A P, Torrent J, et al. What do the HIRM and S-ratio really measure in environmental magnetism?[J].

Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems,2007, 8 .

doi: 10.1029/2007GC001717 ( 0) 0)

|

| 66 |

Liu Q, Banerjee S K, Jackson M J, et al. A new method in mineral magnetism for the separation of weak antiferromagnetic signal from a strong ferrimagnetic background[J].

Geophysical Research Letters,2002, 29 (12) : 10.

( 0) 0)

|

| 67 |

Brachfeld S A. High-field magnetic susceptibility(χhf)as a proxy of biogenic sedimentation along the Antarctic Peninsula[J].

Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors,2006, 156 (3-4) : 274~282.

( 0) 0)

|

| 68 |

Jiang Z, Liu Q, Zhao X, et al. Thermal magnetic behaviour of Al-substituted haematite mixed with clay minerals and its geological significance[J].

Geophysical Journal International,2015, 200 (1) : 130~143.

( 0) 0)

|

| 69 |

Hu P, Liu Q, Torrent J, et al.

Characterizing and quantifying iron oxides in Chinese loess/paleosols:Implications for pedogenesis[M]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2013 : 369 ~370.

( 0) 0)

|

| 70 |

Cornell R, Schwertmann U.

The Iron Oxides:Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Uses[M]. Darmstadt, Germany: John Wiley & Sons, 2006 : 345 ~363.

( 0) 0)

|

| 71 |

Kämpf N, Schwertmann U. Goethite and hematite in a climosequence in Southern Brazil and their application in classification of kaolinitic soils[J].

Geoderma,1983, 29 (1) : 27~39.

( 0) 0)

|

| 72 |

Eyre J K, Dickson D P. Mössbauer spectroscopy analysis of iron-containing minerals in the Chinese loess[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,1995, 100 (B9) : 17925~17930.

( 0) 0)

|

| 73 |

Torrent J, Liu Q, Bloemendal J, et al. Magnetic enhancement and iron oxides in the upper Luochuan loess-paleosol sequence, Chinese Loess Plateau[J].

Soil Science Society of America Journal,2007, 71 (5) : 1570~1578.

( 0) 0)

|

| 74 |

Zhang Y G, Ji J, Balsam W L, et al. High resolution hematite and goethite records from ODP 1143, South China Sea:Co-evolution of monsoonal precipitation and El Niño over the past 600 000 years[J].

Earth and Planetary Science Letters,2007, 264 (1-2) : 136~150.

( 0) 0)

|

| 75 |

Balsam W, Ji J, Renock D, et al. Determining hematite content from NUV/Vis/NIR spectra:Limits of detection[J].

American Mineralogist,2014, 99 (11-12) : 2280~2291.

( 0) 0)

|

| 76 |

Torrent J, Barrón V.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. In:Ulery A L, Drees R eds. Methods of Soil Analysis Part 5:Mineralogical Methods[M]. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: Soil Science Society of America, Inc, 2008 : 367 ~387.

( 0) 0)

|

| 77 |

Torrent J, Barrón V.

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of iron oxides. In:Somasundaran P ed. Encyclopedia of Surface and Colloid Science[M]. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc, 2002 : 1438 ~1446.

( 0) 0)

|

| 78 |

Torrent J, Schwertmann U, Schulze D. Iron oxide mineralogy of some soils of two river terrace sequences in Spain[J].

Geoderma,1980, 23 (3) : 191~208.

( 0) 0)

|

| 79 |

Torrent J, Schwertmann U, Fechter H, et al. Quantitative relationships between soil color and hematite content[J].

Soil Science,1983, 136 (6) : 354~358.

( 0) 0)

|

| 80 |

Judd D B, Wyszecki G.

Color in Business, Science, and Industry[M]. New York: JohnWiley and Sons, 1975 : 553 .

( 0) 0)

|

| 81 |

季峻峰, 陈骏, BalsamW, 等. 黄土剖面中赤铁矿和针铁矿的定量分析与气候干湿变化研究[J].

第四纪研究,2007, 27 (2) : 221~229.

Ji Junfeng, Chen Jun, Balsam W, et al. Quantitative analysis of hematite and goethite in the Chinese loess-paleosol sequences and its imaplication for dry and humid variability[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2007, 27 (2) : 221~229. (  0) 0)

|

| 82 |

Deaton B C, Balsam W L. Visible spectroscopy——A rapid method for determining hematite and goethite concentration in geological materials[J].

Journal of Sedimentary Research,1991, 61 (4) : 628~632.

( 0) 0)

|

| 83 |

Scheinost A, Chavernas A, Barron V, et al. Use and limitations of second-derivative diffuse reflectance spectroscopy in the visible to near-infrared range to identify and quantity Fe oxide minerals in soils[J].

Clays and Clay Minerals,1998, 46 (5) : 528~536.

( 0) 0)

|

| 84 |

Liu Q, Torrent J, Barrón V, et al. Quantification of hematite from the visible diffuse reflectance spectrum:Effects of aluminium substitution and grain morphology[J].

Clay Minerals,2011, 46 (1) : 137~147.

( 0) 0)

|

| 85 |

Jiang Z, Liu Q, Colombo C, et al. Quantification of Al-goethite from diffuse reflectance spectroscopy and magnetic methods[J].

Geophysical Journal International,2014, 196 (1) : 131~144.

( 0) 0)

|

| 86 |

Maher B A. Magnetic properties of modern soils and Quaternary loessic paleosols:Paleoclimatic implications[J].

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,1998, 137 (1) : 25~54.

( 0) 0)

|

| 87 |

Long X Y, Ji J F, Balsam W. Rainfall-dependent transformations of iron oxides in a tropical saprolite transect of Hainan Island, South China:Spectral and magnetic measurements[J].

Journal of Geophysical Research,2011, 116 .

doi: 10.1029/2010JF001712 ( 0) 0)

|

| 88 |

胡鹏翔, 刘青松. 磁性矿物在成土过程中的生成转化机制及其气候意义[J].

第四纪研究,2014, 34 (3) : 458~473.

Hu Pengxiang, Liu Qingsong. The production and transformation of magnetic minerals during pedogenesis and its paleoclimate significance[J]. Quaternary Sciences,2014, 34 (3) : 458~473. (  0) 0)

|

| 89 |

Bond G, Broecker W, Johnsen S, et al. Correlations between climate records from North Atlantic sediments and Greenland ice[J].

Nature,1993, 365 : 143~147.

( 0) 0)

|

| 90 |

Stott L, Poulsen C, Lund S, et al. Super ENSO and global climate oscillations at millennial time scales[J].

Science,2002, 297 (5579) : 222~226.

( 0) 0)

|

| 91 |

Zhang Y G, Ji J, Balsam W, et al. Mid-Pliocene Asian monsoon intensification and the onset of Northern Hemisphere glaciation[J].

Geology,2009, 37 (7) : 599~602.

( 0) 0)

|

| 92 |

Maher B, Prospero J, Mackie D, et al. Global connections between aeolian dust, climate and ocean biogeochemistry at the present day and at the Last Glacial Maximum[J].

Earth-Science Reviews,2010, 99 (1-2) : 61~97.

( 0) 0)

|

| 93 |

Maher B A, Dennis P. Evidence against dust-mediated control of glacial-interglacial changes in atmospheric CO2[J].

Nature,2001, 411 (6834) : 176~180.

( 0) 0)

|

| 94 |

黄春菊. 旋回地层学和天文年代学及其在中生代的研究现状[J].

地学前缘,2014, 21 (2) : 48~66.

Huang Chunju. The current status of cyclostratigraphy and astrochromology in the Mesozoic[J]. Earth Science Frontiers,2014, 21 (2) : 48~66. (  0) 0)

|

| 95 |

Ao H, Dekkers M J, Qin L, et al. An updated astronomical timescale for the Plio-Pleistocene deposits from South China Sea and new insights into Asian monsoon evolution[J].

Quaternary Science Reviews,2011, 30 (13-14) : 1560~1575.

( 0) 0)

|

| 96 |

Yamazaki T, Kanamatsu T. A relative paleointensity record of the geomagnetic field since 1.6Ma from the North Pacific[J].

Earth, Planets, and Space,2007, 59 (7) : 785~794.

( 0) 0)

|

Abstract

Hematite(α-Fe2O3), produced in the dry and warm oxidation environments, is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical areas which records a wealth of significant environmental and climatic information. The concentration of hematite can be used to investigate the precipitation variation and Asian inland aridification evolution. However, precise quantification of hematite is a challenge all the time due to its relative low concentration in nature and weak magnetization. Fortunately, hematite is characterized by high coercivity and typical red color. Based on these characteristics, a series of parameters have been proposed for hematite quantification. Thereby, combined previous and our recent studies on hematite, we summarized the quantification methods of hematite and related limitations, and finally discussed the climatic significances of hematite. Since hematite is magnetically hard with coercivity up to >1T, its contributions to the remanent can be separated by adjusting the applied field, such as hard-fraction of isothermal remanent magnetization(HIRM), AF demagnetization of IRM (IRMAF @ nmT), and so on. In addition, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy(DRS)parameters, e.g. , Redness and Hm/Gt can also be used to quantify hematite. However, these parameters are not only controlled by hematite concentration, but also by the matrixes and ion substitution. These ambiguities can be clarified by combining both magnetic and DRS proxies. These methods have been widely used for the paleoclimatic studies, such as paleorainfall, monsoon evolution and so on. 2016, Vol.36

2016, Vol.36